Vaillancourt2021 articol

- 1. Aggressive Behavior. 2021;47:557–569. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/ab © 2021 Wiley Periodicals LLC | 557 Received: 11 January 2021 | Revised: 14 April 2021 | Accepted: 19 April 2021 DOI: 10.1002/ab.21986 R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E School bullying before and during COVID‐19: Results from a population‐based randomized design Tracy Vaillancourt1,2 | Heather Brittain1 | Amanda Krygsman1 | Ann H. Farrell1 | Sally Landon3 | Debra Pepler4 1 Counselling Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada 2 School of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada 3 Hamilton‐Wentworth District School Board, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada 4 Department of Psychology, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Correspondence Tracy Vaillancourt, Counselling Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Ottawa, 145 Jean‐Jacques‐Lussier, Ottawa, ON K1N 6N5, Canada. Email: tracy.vaillancourt@uottawa.ca Funding information Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Grant/Award Numbers: 201009MOP‐ 232632‐CHI‐CECA‐136591, 201603PJT‐ 365626; Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Grant/Award Numbers: 833‐2004‐1019, 435‐2016‐1251 Abstract We examined the impact of COVID‐19 on bullying prevalence rates in a sample of 6578 Canadian students in Grades 4 to 12. To account for school changes asso- ciated with the pandemic, students were randomized at the school level into two conditions: (1) the pre‐COVID‐19 condition, assessing bullying prevalence rates retrospectively before the pandemic, and (2) the current condition, assessing rates during the pandemic. Results indicated that students reported far higher rates of bullying involvement before the pandemic than during the pandemic across all forms of bullying (general, physical, verbal, and social), except for cyber bullying, where differences in rates were less pronounced. Despite anti‐Asian rhetoric during the pandemic, no difference was found between East Asian Canadian and White students on bullying victimization. Finally, our validity checks largely confirmed previous published patterns in both conditions: (1) girls were more likely to report being bullied than boys, (2) boys were more likely to report bullying others than girls, (3) elementary school students reported higher bullying involvement than secondary school students, and (4) gender diverse and LGTBQ + students reported being bullied at higher rates than students who identified as gender binary or heterosexual. These results highlight that the pandemic may have mitigated bullying rates, prompting the need to consider retaining some of the educational reforms used to reduce the spread of the virus that could foster caring interpersonal re- lationships at school such as reduced class sizes, increased supervision, and blended learning. K E Y W O R D S bullying, COVID‐19, pandemic, prevalence, students 1 | INTRODUCTION The COVID‐19 pandemic has caused unprecedented educational and social disruptions to students globally. For example, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization estimated school closures in 138 countries, affecting 80% of children world- wide (Phelps & Sperry, 2020). In Canada, most students were forced to learn on‐line beginning in March 2020 and did not return to in‐person learning until the following academic year in September 2020. The return to school was however not typical. In Ontario, where the present study was conducted, the Ministry of Education (2020) offered parents of children in Kindergarten to Grade 8 the option to have their child learn in‐person (students attend school full‐time) or virtually (students learn on‐line from home). For sec- ondary students in Grades 9 to 12, designated boards opened using an adaptive model in which class cohorts (half of the class) attended

- 2. in person on alternate days for at least half of the instructional day and then attended remotely with their teachers and classmates for synchronous and/or asynchronous learning the rest of the time. Students could also opt for full‐time e‐learning, taking asynchronous courses through their board and other boards' offerings, a system which predates the pandemic. In addition to these changes, health and safety protocols were implemented which included social distancing, mandatory mask wearing for students in Grades 1 to 12, and changes to how students used school grounds. Elementary (i.e., aged 4‐14 years) and sec- ondary (i.e., aged 13–18 years) cohorts were not permitted to in- teract with other cohorts throughout the day. As a result of these changes, most students in Ontario (which was similar to most pro- vinces in Canada) were being taught in smaller groups and were afforded far less opportunity to interact socially with each other than before the pandemic. Students were also supervised more closely than before the pandemic because the ratio of students to teachers was smaller and because teachers needed to ensure that public health protocols were being followed throughout the school day. Although the impact of these types of educational changes are being considered in relation to students' academic achievement (Dorn et al., 2020) and mental health (Marques de Miranda et al., 2020), to the best of our knowledge, the impact of these changes on students' peer relations has only been examined in three reports, two of which have not been peer‐reviewed and the third currently under review. In the UNICEF Canadian Companion (2020), 93% of participants said they were not bullied online since the lockdown began and 17% said they were bullied less now than before the lockdown. These data were collected from youth aged 13 to 24. There is similar evidence for reduced rates during COVID‐19 from Australia. Data from the Kids Help Line showed a 4% drop in face‐to‐face bullying among children aged 5 to 18 (Yourtown, 2021). This reduction is similar to what is noted when students are out of school for the holidays. Finally, in a Chinese sample of adolescents assessed before the pandemic, during the lockdown, and after school resumed during the pandemic, bullying victimization rates were found to be lower during the lockdown than before the pandemic (Yang et al., 2021). Our aim was to examine the impact of COVID‐19 school changes on bullying prevalence rates using a population‐based randomized design that compared pre‐COVID‐19 rates to current bullying rates in a large sample of students in Grades 4 to 12. 2 | BULLYING VICTIMIZATION AND PERPETRATION Bullying extends beyond the occasional fight or disagreement be- tween peers. Rather, bullying is an enduring experience of psycho- logical distress caused by interpersonal aggression that is repeatedly directed at a person who wields less power than their abuser (Olweus, 1994). Bullying typically takes the forms of physical (e.g., hitting, shoving, stealing, or damaging property), verbal (e.g., name calling, mocking, or making sexist, racist, or homophobic comments), social (e.g., excluding others from a group or spreading gossip or rumours about them), and cyber bullying (e.g., spreading rumours and hurtful comments using e‐mail, cell phones [e.g., text messaging], and on social media sites). The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) emphasize that children have a right to an education that is free from violence and discrimination, yet bullying is a pervasive problem for students worldwide. Ac- cording to population‐based studies, 10% of students are bullied on a regular basis and another 30% of students are bullied occasionally (National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2016; Turner et al., 2018; UNICEF, 2019; Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al., 2010). The Canadian rates for bullying are similarly high. The latest UNICEF Report Card (2019) provides prevalence rates on children's (ages 11 to 15) exposure to chronic bullying victimization, defined as occur- ring at least twice in the past month. According to UNICEF, Canada ranks in the top five of 31 economically advanced countries for the highest bullying victimization rates. Unfortunately, this is an all too familiar problem. For close to three decades, Canada has been at the top of the distribution for bullying victimization (Molcho et al., 2009; UNICEF, 2019). Published population‐based prevalence rates for bullying per- petration tend to be lower than bullying victimization rates, but still disconcertingly high. For example, Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al. (2010) examined the bullying experiences of 16799 Canadian students in Grades 4 to 12 and found that, in response to a general question, 31.7% reported bullying others and 37.6% reported being bullied. When examining bullying by any type, prevalence rates were con- siderably higher; 48.9% reported bullying others and 63.1% reported being bullied. In this study, boys reported bullying others at a higher rate than girls did and reported rates of bullying others were lower in elementary school than in secondary school. Turner et al. (2018) examined bullying victimization in 64174 Canadian students in Grades 7 to 12 using the same cut‐off as Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al. (2010). Similarly high rates were found with 63.2% of adolescents reporting being bullied. In another study involving 11152 Canadian students in Grades 4 to 12, Vaillancourt, Brittain, et al. (2010) ex- amined chronic bullying involvement (i.e., being bullied or bullying others more than 2 or 3 times per month) and found that 12.3% of students were identified as targets of bullying, 5.3% were identified as perpetrators of bullying, and 4.0% were identified as students who both bullied others and were bullied. Slightly more girls than boys were classified as targets of bullying and more boys than girls were classified as students who bully others and as students who both bully others and were bullied. Moreover, more elementary school students were classified as targets than secondary school students and more secondary school students were identified as perpetrators than elementary school students. The negative impact of bullying on those victimized is pervasive, affecting virtually all aspects of functioning— both in the immediate and in the long‐term. Bullying victimization is associated with low self‐esteem, loneliness, depression, anxiety, suicidality, psychosis, disordered eating, and a host of somatic complaints and physical 558 | VAILLANCOURT ET AL.

- 3. health problems (McDougall & Vaillancourt, 2015; Moore et al., 2017). Bullying also affects students' cognitive processes, such as memory and the ability to pay attention (Vaillancourt & Palamarchuk, 2021), making it hard for bullied students to learn and actively participate at school (Schwartz et al., 2005). Students who are bullied by their peers view their school as an unsafe environment (Vaillancourt, Brittain, et al., 2010) and thus avoid attending (Dunne et al., 2010) as a way to prevent or reduce further abuse (Hutzell & Payne, 2012). Given this pattern of cognitive interference and dis- engagement, it is not surprising that bullying victimization is asso- ciated with poor academic achievement (Nakamoto & Schwartz, 2010). The list of difficulties associated with bullying is extensive because bullying damages opportunities for children to develop healthy relationships with their peers. Peer relationships are critical for healthy social‐emotional development (Pepler & Bierman, 2018). When a child's fundamental need to belong is unmet, as is the case with bullying, developmental pathways to adaptive outcomes be- come derailed. Perpetrators of bullying are also at risk. Specifically, mental and physical health, as well as social difficulties such as self‐harm, de- linquency, school adjustment problems, and employment challenges are associated with bullying perpetration (Wolke & Lereya, 2015). One of the most prominent correlates of bullying perpetration is the continued use of aggression within social relationships. Indeed, the abuse of power over others that is practiced in childhood bullying can extend to other forms of violence in adulthood like sexual har- assment, homophobic taunting, and dating violence (Humphrey & Vaillancourt, 2020). Meta‐analytic results further support the con- tinuity of aggression. Childhood bullying perpetration is associated with multiple forms of violence (e.g., assault, carrying weapons, robbery; Ttofi et al., 2012), criminal offending (Ttofi et al., 2011), and dating violence (Zych et al., 2019). There is also longitudinal research demonstrating that being the target of bullying predicts becoming a perpetrator of bullying over time (Barker et al., 2008; Haltigan & Vaillancourt, 2014). 3 | PRESENT STUDY Given the high prevalence rates of bullying in Canada along with the costs borne by targets and perpetrators, our aim was to assess the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on bullying prevalence rates by randomizing students at the level of the school into two conditions— the pre‐COVID‐19 condition and the current condition (during the pandemic). We predicted that the increase in virtual learning along with the organization of smaller groups of students with increased supervision and fewer face‐to‐face interactions would be associated with lower rates in general, and specifically, lower rates in physical, verbal, and social bullying because students had less opportunity to be involved in bullying. This is consistent with recent reports in- dicating a reduction in bullying victimization during the pandemic (UNICEF, 2020; Yang et al., 2021; Yourtown, 2021). In terms of cy- ber bullying rates, because more students were on‐line during the pandemic it is possible that more students would be involved in online bullying; however, the UNICEF Canadian Companion (2020) indicated a 17% reduction in cyber bullying during the pandemic. We thus predicted that cyberbullying rates would also be lower during the pandemic than before the pandemic, albeit the magnitude in difference was expected to be smaller for cyber bullying than for face‐to‐face forms of bullying. We explored whether East Asian Canadian students might be more vulnerable than White students during the pandemic. The anti‐Asian rhetoric associated with the pandemic (Gover et al., 2020) has been linked to increased incidents of racism, discrimination, and violence (Croucher et al., 2020). This prejudice toward East Asians might be associated with higher bul- lying victimization rates among students of East Asian descent compared to White students. Considering the novelty of our research design, we included several validity checks. Specifically, we examined prevalence patterns in relation to known modifiers such as gender, grade division, and sexual minority status (i.e., gender diverse and LGBTQ + students). Population‐based studies of Canadian students suggest that: (1) boys are more often perpetrators of bullying than girls, (2) girls are more often targets of bullying than boys, and (3) students in elementary school are more involved in bullying than students in secondary school (Vaillancourt, Brittain, et al., 2010; Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al., 2010). Moreover, studies consistently demonstrate that sexual minority students are bullied at the highest rate of any student (Cénat et al., 2015; Mennicke et al., 2020). We expected to find similar patterns of results in the pre‐COVID‐19 and current conditions. 4 | METHODS 4.1 | Participants A total of 9095 students in Grades 4 to 12 accessed the survey either at school or at home using their personal or a board provided device. In the pre‐COVID‐19 condition, 1442 students had data that were not usable because they had no data (n = 382), incomplete data (n = 706), did not provide assent (n = 138), or were flagged for invalid responses (n = 216). In the current condition, 1075 students had unusable data because they had no data (n = 342), incomplete data (n = 442), did not provide assent (n = 115), or were flagged for invalid responses (n = 176). The final analytic sample consisted of 6578 students in Grades 4 to 12 (M age=13.05 years; SD = 2.34; MIN = 8.00; MAX = 19.00) who completed the survey. In the pre‐COVID‐19 condition, 3895 (49.3% girls, 44.8% boys, 2.1%1 gender diverse) students completed the survey and in the current condition, 2683 students (44.8% girls, 50.0% boys, 2.6% gender diverse) completed the survey. The current condition had fewer students than the pre‐COVID‐19 condition be- cause randomization occurred at the school level and not all schools were the same size. Schools randomized to the pre‐COVID condition had 9.9% more students available at the elementary level and 26.1% more students at the secondary school level. VAILLANCOURT ET AL. | 559

- 4. In terms of other demographic features, in the pre‐COVID‐19 condition, 42.2% of students identified as White and 29.1% as be- longing to an underrepresented racial group, while in the current condition, 46.7% of students identified as White and 32.1% as be- longing to an underrepresented racial group. Most students attended school in person during the pandemic, beginning in September 2020: elementary school (97.8%) and secondary school (84.8%). Parent consent and student assent were obtained for all parti- cipants. Most parents (94.0%) of eligible students consented to have their child participate and most students provided assent to parti- cipate in the pre‐COVID (97.6%) and current (97.0%) conditions. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Ottawa's Re- search Ethics Board (REB) and the Hamilton‐Wentworth District School Board's REB. 4.2 | Procedures As part of a Safe Schools audit, students were randomized at the level of the school into the pre‐COVID‐19 condition and the current condition to account for the COVID‐19 pandemic. In these conditions, students were asked to consider their retrospective experiences within a specified timeframe. The timeline for the pre‐COVID‐19 condition was September 2019 to March 2020 and for the current condition it was from the start of September 2020 until November 2020. For students enrolled in the in‐person learning program, class- room teachers provided school‐owned devices to students and had students access the survey, which assessed various aspects of school safety including the measures described below. Students took 15.31 min (median) to complete the survey. A survey code was given to each school based on their randomization assignment and this code populated the appropriate survey by condition. Teachers in- formed students of their rights as participants including the assur- ance of anonymity and the right to skip any question they wanted to. Following recommendations by Vaillancourt et al. (2008), teachers read out loud a definition to students before granting access to the survey. The definition differentiated bullying from general aggression and teasing: There are a lot of different ways students get bullied. Bullying can be physical, verbal, social, or online. A stu- dent who bullies wants to hurt the other person (it's not an accident), and they do it more than once and in an unfair way (the person bullying has some advantage over the person they are bullying). Sometimes a group of stu- dents will bully another student. It is not bullying when two students of about the same strength or popularity have an argument or disagreement. Parents of younger students (Grades 4 to 8) and secondary school (Grades 9 to 12) students enrolled in virtual learning pro- grams were provided with an instruction sheet that clearly delineated the timeframe to consider when responding and the de- finition of bullying. Parents were asked to allow their child to fill out their survey alone after setting them up with the survey and con- veying these two important points (timeframe and definition), which were also clearly noted on the surveys. Technical support was available to teachers, students, and parents. 4.3 | Measures 4.3.1 | Bullying victimization and perpetration Bullying victimization and perpetration were assessed with five self‐ report items from an adapted version of the widely used Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (Olweus, 1994; Vaillancourt, Brittain, et al., 2010; Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al., 2010). Students were asked first to read the aforesaid definition of bullying and then asked about their general experience with bullying victimization (“How often were you bullied by another student(s)?”) followed by questions assessing phy- sical, verbal, social, and cyber bullying victimization that included be- havioural descriptors for each form. These questions were then repeated to assess bullying perpetration (“How often have you bullied other student(s)?”). A five‐point scale was used to assess each item (0 = not at all to 4 = many times a week). Cronbach's α was good for bullying victimization in both conditions (pre‐COVID α = .83; current α = .80), as well as for bullying perpetration (pre‐COVID α = .77; cur- rent α = .82) supporting the reliability of the scales in both conditions. 4.3.2 | Demographic questions Students were asked about the program of learning they were cur- rently taking: (1) “Elementary in‐person (you go to school full‐time)”; (2) “Elementary virtual (you go to school from home)”; (3) “Secondary adaptive alternate cohorts (or rotational model)”; and (4) “Secondary e‐learning.” Students were also asked to indicate their current grade, their age, their gender, their sexual orientation (Grades 7 to 12 only), and their racial background using multiple choice and checkbox options. 4.3.3 | Validity screening Anonymous student surveys run the risk of having invalid responses (Cornell et al., 2012, 2014). We screened for data integrity using three questions by Cornell et al. (2012): (1) “I am telling the truth on this survey”; (2) “I am not paying attention to how I answer this survey”, and (3) “The answers I have given on this survey are true.” We also screened the open‐ended questions for implausible re- sponses such as listing being an alien under the race question and having unlikely times to complete the survey. Students with invalid responses were excluded from subsequent analyses (<5% of re- sponses were invalid). 560 | VAILLANCOURT ET AL.

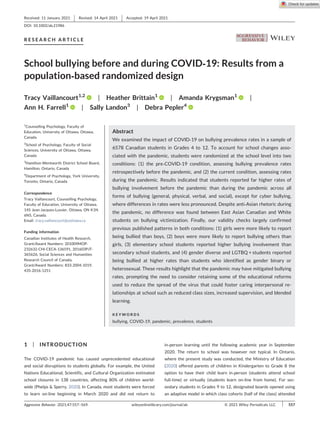

- 5. 4.4 | Analytic plan Bullying involvement (prevalence) was calculated by using the cut‐off point shown by Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al. (2010) as having the best specificity and sensitivity (no involvement vs. any involvement) and has been used in other population‐based studies examining bullying in- volvement prevalence (e.g., Craig et al., 2020; Turner et al., 2018). Spe- cifically, data from the general screening questions were combined into binary bullying experience groups for targets (been bullied) and perpe- trators (bullied others). These groups were calculated as follows: (a) those reporting never being bullied or never bullying others (coded as “0,” noninvolved) and (b) those reporting some level of involvement with bullying ranging from only a few times to every week (coded as “1,” involved). Prevalence rates were assessed using Multi‐Way Frequency Ana- lyses (MFA), a nonparametric analysis similar to analysis of variance that tests associations between multiple categorical variables by comparing observed and expected frequencies (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). The results of MFA can be influenced by inadequate expected cell frequencies (i.e., 20% of cells under five; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Expected cell frequencies in all analyses exceeded five. In these analyses, bullying involvement (target or perpetrator) was conceptualized as the dependent variable and condition (pre‐COVID 19 vs. current), gender (girls vs. boys), and grade level (elementary vs. secondary) were con- sidered independent variables. In MFA, the loglinear model begins by testing the higher order associations (e.g., condition by gender by bullying experience) followed by all two‐way, then one‐way associations. Asso- ciations that are not statistically significant are eliminated. In the present study, we were not interested in establishing a model and therefore we restricted our analyses to an examination of reliable variations in bullying involvement and experience (i.e., by form of bullying) as a function of condition by gender/grade, similar to Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al. (2010). We addressed our potentially high false discovery rate by applying the Benjamini‐Hochberg procedure (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). Only p‐values for the interaction terms of interest were included, that is bullying experience by condition, bullying experience by condition by gender/grade, bullying experience by gender/grade, bullying victimization (any form) by condition by race/gender diversity/sexual orientation, and bullying victimization (any form) by race/gender diversity/sexual orientation (n = 66 comparisons). 5 | RESULTS 5.1 | Prevalence of bullying involvement by condition Examining prevalence rates of bullying experiences by form by con- dition revealed reliably higher rates pre‐COVID‐19 compared to current rates (Table 1), consistent with our initial predictions. For example, when examining all forms as a composite, 59.8% (n = 2312) of students reported being bullied before the pandemic compared with 39.5% (n = 1052) of students who reported being bullied in the current condition. In terms of perpetration, 24.7% (n = 951) reported bullying others pre‐COVID‐19, while 13.0% (n = 347) of students re- ported bullying others in the current condition. As predicted, rates of physical, verbal, social, and cyber bullying victimization and perpe- tration were higher before the pandemic than during the pandemic. 5.2 | Racial bullying victimization The three‐way interaction between condition, White/East Asian, and victimization (any form) was not statistically significant, χ2 (1, 3110) = 2.500, p = .114, indicating that differences in rates of victimization for White and East Asian students did not differ before and during the TABLE 1 Proportion of Involved Students by Experience Type and Condition Experiences Condition × Experience Pre‐COVID involved (%/n) Current involved (%/n) Victimization (general) χ2 (1, 6411) = 236.277, p < .001 34.3 (1305) 16.9 (442) Physical victimization χ2 (1, 6418) = 128.968, p < .001 21.5 (818) 10.7 (280) Verbal victimization χ2 (1, 6430) = 170.593, p < .001 40.2 (1531) 24.5 (642) Social victimization χ2 (1, 6397) = 239.930, p < .001 44.7 (1696) 25.6 (666) Cyber victimization χ2 (1, 6433) = 7.644, p = .006 13.8 (528) 11.5 (301) Victimization (all forms + general) χ2 (1, 6530) = 260.573, p < .001 59.8 (2312) 39.5 (1052) Bullying (general) χ2 (1, 6403) = 81.833, p < .001 11.9 (449) 5.3 (138) Physical bullying χ2 (1, 6441) = 21.306, p < .001 5.6 (212) 3.1 (82) Verbal bullying χ2 (1, 6425) = 41.463, p < .001 11.9 (451) 7.0 (184) Social bullying χ2 (1, 6419) = 111.646, p < .001 13.8 (525) 5.6 (147) Cyber bullying χ2 (1, 6445) = 6.454, p = .011 3.4 (130) 2.3 (61) Bullying (all forms + general) χ2 (1, 6505) = 134.483, p < .001 24.7 (951) 13.0 (347) Note: All Condition × Experience were statistically significant following the Benjamini‐Hochberg procedure. VAILLANCOURT ET AL. | 561

- 6. COVID‐19 pandemic. The two‐way interaction between race and victi- mization was also not significant, χ2 (1, 3110) = 2.815, p = .093, indicating that White and East Asian students reported similar rates of victimiza- tion. In the pre‐COVID condition, 61.1% (n = 1002) of White students and 50.4% (n = 61) of East Asian students reported being bullied. In the current condition, 38.0% (n = 475) of White students and 38.4% (n = 38) of East Asian students reported being bullied. 5.3 | Validity check We examined interactions by condition by gender2 by bullying experi- ences (Table 2) and by condition by grade by bullying experiences (Table 3) and found that only two of the three‐way interactions were statistically significant (verbal victimization by condition by grade and bullying perpetration (any form) by condition by grade) suggesting that gender and grade trends were relatively similar across condition (i.e., same direction but different magnitude), as would be expected given the randomization of students at the level of schools. Specifically, as pre- dicted, girls reported higher rates of bullying victimization than boys across all forms, except for physical bullying victimization, which was higher for boys than for girls. As expected, girls reported lower bullying perpetration rates than boys on the general bullying, physical bullying, and verbal bullying questions. Girls and boys reported approximately equal rates of social and cyber bullying perpetration. In terms of grade differences, as predicted, students in elementary school reported higher TABLE 2 Proportion of involved students by experience type, condition, and gender Proportion score within gender (% involved/n) Experiences Condition × Experience × Gender Experience × Gendera Pre‐COVID Current Victimization (general) NS χ2 (1, 6070) = 14.989, p < .001 B = 30.8 (530) B = 14.7 (194) G = 36.1 (675) G = 17.7 (205) Physical victimization NS χ2 (1, 6073) = 53.180, p < .001 B = 25.5 (439) B = 12.0 (158) G = 16.6 (309) G = 8.2 (96) Verbal victimization NS χ2 (1, 6082) = 15.195, p < .001 B = 36.9 (634) B = 21.9 (288) G = 42.2 (793) G = 25.4 (297) Social victimization NS χ2 (1, 6054) = 161.657, p < .001 B = 34.9 (598) B = 19.4 (254) G = 52.6 (983) G = 31.4 (364) Cyber victimization NS χ2 (1, 6084) = 39.044, p < .001 B = 10.1 (175) B = 9.1 (120) G = 16.4 (306) G = 12.9 (150) Victimization (all forms + general) NS χ2 (1, 6174) = 46.103, p < .001 B = 53.8 (938) B = 36.0 (480) G = 64.3 (1225) G = 41.6 (496) Bullying (general) NS χ2 (1, 6059) = 15.547, p < .001 B = 13.3 (226) B = 6.4 (84) G = 10.3 (192) G = 3.6 (42) Physical bullying NS χ2 (1, 6091) = 30.427, p < .001 B = 7.6 (130) B = 3.8 (50) G = 3.7 (70) G = 2.2 (26) Verbal bullying NS χ2 (1, 6081) = 18.187, p < .001 B = 13.2 (227) B = 8.9 (117) G = 10.5 (196) G = 4.9 (58) Social bullying NS χ2 (1, 6074) = 4.395, p = .036b B = 12.5 (214) B = 5.3 (69) G = 14.8 (227) G = 5.9 (69) Cyber bullying NS χ2 (1, 6099) = 0.864, p = .353 B = 3.6 (62) B = 2.4 (31) G = 3.2 (60) G = 1.9 (23) Bullying (all forms = general) NS χ2 (1, 6151) = 12.795, p < .001 B = 26.4 (458) B = 14.7 (196) G = 22.9 (433) G = 11.0 (131) Note: B, boys; G, girls. a Partial χ2 statistic and p value. b The effect of social bullying perpetration × condition was not statistically significant following the Benjamini‐Hochberg procedure. 562 | VAILLANCOURT ET AL.

- 7. rates of bullying involvement than students in secondary school, with three exceptions: (1) there was no grade difference for cyber bullying victimization or perpetration, (2) rates of verbal victimization were found to vary by grade and by condition, and (3) rates of verbal victimization and perpetration (any form) were found to vary by grade and condition. Further, the rate of verbal victimization for elementary students in the current condition was 72% of the pre‐COVID rate, whereas current secondary school verbal bullying was approximately half that of the pre‐ COVID rate. A similar pattern was found for bullying perpetration (any). We also examined gender diversity as a validity check and found that the three‐way interaction between condition, gender diversity (gender diverse/binary), and victimization (any form) was not sta- tistically significant, χ2 (1, 6326) = 0.427, p = .513, indicating that dif- ferences in victimization rates between gender diverse and binary students did not depend on condition. There was a statically sig- nificant two‐way interaction between gender diversity and victimi- zation, χ2 (1, 6326) = 23.786, p < .001. An inspection of the proportion victimized indicated that gender diverse students reported higher rates of victimization pre‐COVID (diverse = 79.7%, n = 63; binary = 59.3%, n = 2163) and during the pandemic (diverse = 57.1%, n = 40; binary = 38.6%, n = 977). Finally, results for sexual orientation mirrored those for gender diversity. The three‐way interaction was not statistically significant, χ2 (1, 3344) = 0.001, p = .980; however, the two‐way interaction be- tween sexual orientation and victimization (any form) was statisti- cally significant, χ2 (1, 3344) = 64.911, p < .001. Results indicated that there were differences in rates of victimization between students reporting heterosexual and diverse sexual orientations that did not TABLE 3 Proportion of involved students by experience type, condition, and grade Proportion score within grade (% involved/n) Experiences Condition × Experience × Grade Experience × Gradea Pre‐COVID Current Victimization (general) NS χ2 (1, 6411) = 105.711, p < .001 E = 39.3 (904) E = 21.7 (284) S = 26.8 (401) S = 12.2 (158) Physical victimization NS χ2 (1, 6418) = 323.756, p < .001 E = 28.9 (664) E = 17.2 (225) S = 10.2 (154) S = 4.2 (55) Verbal victimization χ2 (1) = 11.682, p < .001 χ2 (1, 6430) = 72.682, p < .001 E = 43.2 (999) E = 31.0 (409) S = 35.5 (532) S = 17.9 (223) Social victimization NS χ2 (1, 6397) = 86.258, p < .001 E = 49.6 (1140) E = 30.2 (392) S = 37.1 (556) S = 21.1 (227) Cyber victimization NS χ2 (1, 6433) = 7.473, p = .006 E = 12.6 (291) E = 10.9 (143) S = 15.8 (237) S = 12.0 (158) Victimization (all forms + general) NS χ2 (1, 6530) = 166.441, p < .001 E = 65.5 (1541) E = 48.2 (647) S = 50.9 (771) S = 30.7 (405) Bullying (general) χ2 (1) = 4.121, p = .042b χ2 (1, 6403) = 31.253, p < .001 E = 13.5 (307) E = 7.2 (95) S = 9.5 (142) S = 3.3 (43) Physical bullying NS χ2 (1, 6441) = 109.21, p < .001 E = 7.9 (182) E = 5.2 (58) S = 2.0 (30) S = 1.1 (14) Verbal bullying NS χ2 (1, 6425) = 29.482, p < .001 E = 13.4 (306) E = 9.2 (121) S = 9.6 (149) S = 4.8 (63) Social bullying NS χ2 (1, 6419) = 24.549, p < .001 E = 15.5 (355) E = 7.2 (94) S = 11.3 (170) S = 4.0 (53) Cyber bullying NS χ2 (1, 6445) = 1.140, p = .286 E = 3.1 (72) E = 2.3 (30) S = 3.9 (58) S = 2.4 (31) Bullying (all forms + general) χ2 (1) = 7.000, p = .008 χ2 (1, 6505) = 74.390, p < .001 E = 27.9 (651) E = 17.5 (235) S = 19.9 (19.9) S = 8.5 (112) Note: E = elementary school (Grades 4–8), S = secondary school (Grades 9–12). a Partial χ2 statistic and p value. b The effect of perpetration (general) × condition × grade was not statistically significant following the Benjamini‐Hochberg procedure. VAILLANCOURT ET AL. | 563

- 8. vary in magnitude as a function of the pandemic. Students with di- verse sexual orientations reported significantly higher rates of bul- lying victimization in both the pre‐COVID (diverse = 67.8%, n = 387; heterosexual = 53.0%, n = 621) and current (diverse = 49.9%, n = 212; heterosexual = 34.7%, n = 408) conditions. 6 | DISCUSSION The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on students' academic achieve- ment (e.g., Dorn et al., 2020) and mental health (e.g., Marques de Miranda et al., 2020) is being investigated in earnest. However, what has largely been ignored during these trying times is how school‐related changes, designed to keep students safe during the pandemic, may have affected students' social relationships/interactions, and in particular, their ex- periences with bullying. There is good reason to expect a “silver lining” with regard to bullying rates during the pandemic. With decreased class sizes, increased supervision, and fewer opportunities to interact socially at school, bullying victimization and perpetration rates should be lower during the pandemic than before the pandemic. We tested this as- sumption using a population‐based randomized design that compared bullying rates before and during the pandemic in a sample of students in Grades 4 to 12. Although our aim was simple, the knowledge gained is important for the prevention of bullying. For example, researchers and educators have argued that increased supervision is critical for the re- duction of bullying (Vaillancourt, Brittain, et al., 2010; van Verseveld et al., 2019). There has also been a push to reduce class sizes so that caring relationships between students and teachers and among students can be forged (Finn et al., 2003), although the evidence on smaller class sizes and bullying reductions is mixed (e.g., Azeredo et al., 2015). Still, improving relationships can reduce bullying (Khoury‐Kassabri et al., 2004), while also potentially improving academic achievement (Nye et al., 2000). The pandemic has brought these educational changes (e.g., re- duced class size, increased supervision) to fruition, but has an associated reduction in bullying rates also occurred? When we examined bullying prevalence rates across the two conditions, we found notable differences. Specifically, students reported far greater involvement in bullying as targets and perpetrators before the pandemic than during the pandemic. For example, when we examined rates using a composite variable that included a general question about bullying along with specific questions about forms of bullying (i.e., physical, verbal, social, and cyber), we found that 59.8% of students reported being bullied before the pandemic compared with 39.5% who reported being bullied during the pandemic. These striking differences were also found when examining bullying perpetration rates—24.7% pre‐COVID‐19 versus 13.0% current. Although it is possible that these differences in rates are driven by timeframe differences between the two conditions, we suspect that this is not the case given that high proportions obtained in the pre‐pandemic condition are in keeping with those obtained by Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al. (2010), a decade earlier, from students in the same grades and school district and using the same cut‐off and measure. In this study, 63.1% of students were involved in bullying as targets and 48.9% as perpetrators. Turner et al. (2018) also found in their population‐based study that 63.2% of Canadian youth in Grades 7 to 12 were bullied by their peers. Of note, Turner et al. asked students to report on their experiences with bullying in the past year, while Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al. (2010) asked them to report on their experiences using the same timeframe as the current (pandemic) condition (i.e., 3 months; September to November) and yet it is the pre‐COVID‐19 rates, with the longer timeframe, that map onto Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al. (2010) and Turner et al. and not the current condition rates, with the timeframe identical to Vaillancourt et al. These consistencies help demonstrate validity but also highlight a dismal reality in Canadian schools, one that is echoed in the UNICEF world reports of students from economically advanced nations. That is, whereas most countries are showing declines in bullying involvement, for Canada, our rates are steadfast and high (Molcho et al., 2009; UNICEF, 2019). We predicted that involvement with specific forms of bullying would be higher in the pre‐COVID‐19 condition than in the current condition. In particular, we expected students to report higher rates of physical, verbal, and social bullying before the pandemic. As for cyber bullying, our prediction was more tentative. The prominent virtual component associated with the pandemic could be associated with higher cyber bullying rates, but a recent Canadian UNICEF report (2020) noted a 17% reduction in online bullying during the pandemic. With this new report in mind, we expected less cyber bullying during the pandemic than before the pandemic but the difference in magni- tude would be smaller when compared to face‐to‐face forms of bul- lying. Bullying involvement was indeed a lot higher for physical, verbal, and social bullying before the pandemic than during the pandemic, while cyber bullying rates were only slightly higher before the pan- demic than during the pandemic. Although students are on‐line more now than before the pandemic, this has not translated to higher rates of cyber bullying involvement. In fact, our results support the opposite conclusion. The finding of slight reductions in cyber victimization and bullying might be related to the close monitoring of virtual activities by teachers and parents, many of whom have been tasked with su- pervising their children one‐on‐one at home. We explored whether students of East Asian heritage were bullied more during the pandemic than before the pandemic in consideration of the anti‐Asian rhetoric (Gover et al., 2020) and in- creased incidents of racism, discrimination, and violence (Croucher et al., 2020) associated with COVID‐19. Results indicated that stu- dents of East Asian decent did not report higher rates of bullying victimization during the pandemic (or before the pandemic) than their White peers. Although this is reassuring, and consistent with meta‐analytic findings (Vitoroulis & Vaillancourt, 2015), it does not mean that Asian students are necessarily spared in different regions in Canada or in different countries that vary in their level of racist rhetoric and bigoted behaviour. For instance, in the United States, former president Donald Trump consistently referred to COVID‐19 using a racial slur, which has been cited as having an impact on hate crimes and racial bullying during the pandemic (Cruz et al., 2020). Our primary validity check was to examine whether our pattern of findings were consistent with other published studies in terms of gender, grade, gender diversity, and sexual orientation. We undertook this step because students were asked to retrospectively report on 564 | VAILLANCOURT ET AL.

- 9. their experience before the pandemic. Though we were confident that our approach was sound because bullying is such a salient experience and one that students seldom forget (see neuroscience review by Vaillancourt & Palamarchuk, 2021), we nevertheless carried out this important validation check. Based on Vaillancourt, Brittain, et al. (2010), and Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al. (2010), we predicted that across the two conditions, girls would report more involvement with victi- mization than boys and that boys would report more involvement with perpetration than girls. We also expected that elementary school students would have more involvement with bullying than secondary school students (Vaillancourt, Brittain, et al., 2010; Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al., 2010). Finally, we expected that sexual minority students would be bullied at higher rates than students who identified as gender binary and heterosexual, as has been shown in other studies (Cénat et al., 2015; Mennicke et al., 2020). Our results largely confirmed previous patterns in both conditions—girls were more likely to report being bullied than boys, boys reported bullying others at a higher rate than girls, with the exception of social bullying perpetration (girls > boys) which was not significant following the Benjamini‐Hochberg procedure. Students in elementary school reported both bullying others and being bullied at higher rates than students in secondary school, with the exception of cyber bullying where secondary school students reported slightly higher victimization rates than elementary school students. Grade was not, however, associated with cyber bullying perpetration rates. Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al. (2010) found that involvement in cyber bullying as a target or perpetrator peaked in early secondary school. In our analyses of gender and grade, only two of our three‐way interactions were statistically significant suggesting that while the mag- nitude of the differences were dissimilar between conditions on rates, the pattern of findings was the same across the two conditions. The two exceptions were the three‐way interactions for condition by grade by verbal victimization and condition by grade by bullying perpetration (any form). Probing these findings suggests that secondary students' rates during the pandemic were substantially lower than pre‐pandemic rates, as compared to the difference in elementary school students' rates. Specifically, rates of verbal victimization for secondary school students were lower during the pandemic than pre‐pandemic by ap- proximately 50%, whereas elementary students' experience of verbal victimization were lower by only 28%. Similarly, pandemic rates of bul- lying perpetration (any form) were 57% lower than pre‐pandemic rates for secondary students and only 37% lower than pre‐pandemic rates for elementary students. Gender diverse and LGTBQ + students reported being bullied at higher rates than those who identified as gender binary or heterosexual in both conditions. 6.1 | Limitations The strength of our study is that we used an experimental design and randomized students (at the school level) to report on their experiences with bullying before and during the pandemic. Another strength is that we included several validity checks and added screening questions to assess invalid responses (Cornell et al., 2012, 2014). Despite these strengths in design, there are limitations to consider. First, the timeframe was not equivalent in the pre‐COVID‐19 and current conditions, which could have inflated pre‐pandemic results because students had a longer period to consider. We suspect this did not happen because students were asked the same questions using the same response format that ranged from not at all to many times a week and thus likely defaulted to a general pre‐pandemic versus pandemic timeframe. Indeed, the timeframe differences do not seem to have had a notable impact on our results insofar as the prevalence rates obtained in the pre‐pandemic condition (six month timeframe) paralleled those obtained by Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al. (2010) even though Vaillancourt et al. asked students about their experiences with bullying using a “past three months” timeframe. This three month timeframe is the same one used in the current condition yet the rates obtained before the pandemic using a six month timeframe are the ones that replicate Vaillancourt et al.'s rates. Incidentally, Vaillancourt et al. also collected data in late fall of the school year, which is the same data collection schedule as the current condition and data were collected in the same school district. Still, given these differences, replication is needed. Moreover, more attention needs to be paid to the impact of timeframes in general on bullying prevalence rates in children and youth. We suspect that given the salience of bullying, victimization is not likely to be easily forgotten and thus timeframe difference of three months compared to six months will not have much of an impact on rates. In a recent study by Beltran‐Catalan and Cruz‐Catalan (2020), the best cut‐ off point to use, based on their ROC curve analysis, was “more than six months”. This was likely because bullying typically lasted longer than six months for most youth (72.6%) in their study. Indeed, they found that targets of bullying reported that the duration of their bullying experi- ences was three years on average. In a study involving adults, Green et al. (2018) found that the recall of bullying was stable, as did Rivers (2001), who reported that “participants were able to recall key events in their lives and place them within a general chronology which was not found to vary across the 12–14 month period” (p. 129). In other words, adult participants were accurate about the time and duration of their bullying experiences. Olweus (1993) also found that former targets of bullying were accurate in their appraisal of the severity of their childhood abuse up to seven years later. This is consistent with the broader literature that finds that most individuals can recall past events accurately across time. Specifically, autobiographical memories (which is what bullying experi- ences are) have been shown to be “remarkably robust” after a number of years even in very young children (Peterson, 2002). Importantly, emo- tional and thematic coherence of original memories have been found to increase memory survivability (Bauer et al., 2019; Peterson et al., 2014). It will be important to also address if the same robustness is found when examining bullying perpetration. It is likely that the recall of the abuse of others is more susceptible to biases because of factors like moral dis- engagement, cognitive dissonance, and social desirability. Second, when assessing prevalence rates by form, we did not ask specifically about racial bullying. According to Vitoroulis and Vaillancourt (2015), the lack of reference to race/ethnicity when assessing bullying can lead to an underestimation of the prevalence of peer victimization experienced by racial and ethnic minority VAILLANCOURT ET AL. | 565

- 10. students. They also suggest that “ethnicity as a demographic variable is not sufficient to draw conclusions on inter‐ or intra‐ethnic peer victimization” and recommend the inclusion of other variables that are “pertinent to ethnic identity, acculturation and immigration sta- tus” (p. 165). Third, it is common for cyber bullying in particular to be treated as a distinct form of bullying in the scientific literature, the media, and in education. However, studies using sophisticated ana- lytic techniques to assess the overlap and uniqueness of the various forms of bullying suggest that there is substantial commonality; all forms of bullying overlap and co‐occur, are predicted by similar factors, and are associated with comparable outcomes (Haltigan & Vaillancourt, 2018; Nylund et al., 2007). Accordingly, the best pre- valence estimates for the present study are likely those derived from the five‐item composite, consistent with Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al. (2010). Fourth, the students who completed the survey at‐home did not have the same support as those who completed the survey at school. The presence of a bullying definition (or not) has been shown to have an impact on prevalence rates (Vaillancourt et al., 2008). In the present study, we cannot be sure if students who completed the survey at home attended to the definition of bullying the same way students did at school. Fifth, not all eligible students accessed the survey, and of the 9095 students who did, only 6578 (72%) completed the survey. It is possible that students who were involved with bullying were more motivated to participate in the study than students not involved. However, it is worthy to mention again that our pre‐COVID rates were similar to those obtained by Vaillancourt, Trinh, et al. (2010) who surveyed 98% of eligible students. Sixth, our assumption is that bullying victimization and perpetration were lower during the pandemic than before the pandemic because of school‐related factors like decreased class sizes, increased supervision, and the fewer opportunities for them to interact socially at school, but other factors could be at play. Students get bullied and bully others on their way to and from school (Vaillancourt, Brittain, et al., 2010) and peer conflicts in the community can spill over to the school environment. In Canada, there have been notable restrictions on social gatherings of children and adults. As one example, extra- curricular activities like community sports have been cancelled in many areas. These restrictions could also influence bullying in- volvement rates before and during the pandemic. Finally, we were not permitted to code school level data as per our agreement with the participating school board, and therefore, we were not able to examine school‐level variation. Such information could have been used to explore factors like difference in school ethnic composition and involvement with bullying similar to Vitoroulis et al. (2016) but in the context of the pandemic. 6.2 | Implications The present study was conducted in Ontario, Canada where the Education Act expects assiduous care for the health of students, which means unrelenting support for students, especially the most vulnerable ones (Accepting Schools Act, 2012; Education Act, 1990). When reporting on bullying involvement before the pandemic, three of every five students reported having been bullied. The prevalence rate was lower among those students reporting on experiences during the pandemic, with two of every five students reporting being bullied. In our research, gender diverse and LGBTQ+ students were at the highest risk of bullying victimization; four out of every five reported being bullied pre‐COVID and three out of every five re- ported being bullied during the pandemic. These disquieting statistics suggest that the Education Act's (1990) first responsibility for prin- cipals and teachers to provide assiduous care falls short for far too many students. This responsibility must be in place before the sec- ond responsibility, educating students, can be implemented effec- tively, especially for the most marginalized students. Assiduous care is also critical for students who bully because like bullied students (McDougall & Vaillancourt, 2015; Moore et al., 2017), they too are at risk for a wide range of health, social, and school adjustment pro- blems (Wolke & Lereya, 2015). Youth who bully also need to be identified and supported in developing healthy relationship patterns to establish a foundation for positive adaptation and relationships across the lifespan. The shifts in patterns of bullying involvement from the pre‐pandemic to the pandemic periods indicate that bullying is not an individual pro- blem but a social power dynamic that unfolds in the context of peer groups and the school system. Therefore, bullying problems must be addressed through systemic changes at all levels within the education system and with proactive efforts to ensure that all students are safe and able to learn. Systemic change to address bullying is the responsibility of all those within the system—policy makers, senior administration, prin- cipals, teachers, parents, and students. These changes can only be made, however, by engaging students as change partners (Spears et al., 2011), as they are the experts on the ground in school bullying; they know the problems and can envision the solutions (Cunningham et al., 2010, 2016). Finally, our results highlight that the pandemic seems to have had a positive effect on bullying rates, which prompts the need to consider retaining some of the educational reforms used to reduce the spread of the virus such as increased supervision, reduced class sizes, and blended learning. Increased supervision is essential for the reduction of bullying (Vaillancourt, Brittain, et al., 2010; van Verseveld et al., 2019), while smaller class sizes may help foster caring relationships (Finn et al., 2003), which could help reduce bullying (Khoury‐Kassabri et al., 2004), and improve academic achievement (Nye et al., 2000). When we mention increased supervision, we do not mean increases in security cameras or police officers in schools. Rather we mean chan- ges to the number of teachers or other caring adults who are physi- cally present to supervise students outside of class. Blended learning— combining traditional, in‐person instruction with online learning—has potential to afford more options to students who do not thrive in the traditional classroom. To date the evidence on blended learning sug- gests better academic performance when compared to traditional face to‐face instruction (see review by Means et al., 2013). Blended learning seems to also outperform online only learning. For example, a recent study of 4th grade students showed that blended learning was associated with increases in students' engagement (Kundu et al., 2021) 566 | VAILLANCOURT ET AL.

- 11. and in an experimental study of elementary students, greater reading gains were found for blended group than the control group (Macaruso et al., 2020). Most of the studies conducted to date have been on adult learners, so more work is needed to assess this in younger learners and at‐risk students (Pytash & O'Byrne 2018; Repetto et al., 2018). Schools need to be safe places that promote optimal learning and development. Our study suggests that there is a long way to go for Canada to achieve such a goal. CONFLICT OF INTERESTS The authors declare no known conflicts of interest. Parts of this study, authored by Tracy Vaillancourt, Debra Pepler, and Ann Farrell, were reported in the Safe Schools Panel Report for the Hamilton‐ Wentworth District School Board. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study was funded by grants awarded to Tracy Vaillancourt by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (grant numbers 833‐2004‐1019, 435‐2016‐1251) and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant numbers 201009MOP‐232632‐ CHI‐CECA‐136591, 201603PJT‐365626‐PJT‐CECA‐136591). Hea- ther Brittain is supported by a SSHRC Vanier scholarship and Ann H. Farrell is supported by a SSHRC Banting Fellowship. PEER REVIEW The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons. com/publon/10.1002/ab.21986. DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. ENDNOTES 1 Students were given the option of skipping any of the questions asked, therefore not all proportions will equal 100%. 2 Because gender is usually treated as a binary variable (i.e., girls vs. boys), students who identified as gender diverse (i.e., fluid, intersex, nonbinary/ gender non‐conforming for Grades 7 to 12 and other for Grades 4 to 6) were not included in these analyses so that comparisons to other pub- lished studies could be made. These students were included in a sub- sequent validity check analysis. ORCID Tracy Vaillancourt http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9058-7276 Heather Brittain http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6070-3689 Amanda Krygsman http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1398-7572 Ann H. Farrell http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9947-3358 Debra Pepler http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2505-289X REFERENCES Accepting Schools Act. (2012). S.O. c. 5—Bill 13. https://www.ontario.ca/ laws/statute/s12005 Azeredo, C. M., Rinaldi, A. E. M., de Moraes, C. L., Levy, R. B., & Menezes, P. R. (2015). School bullying: A systematic review of contextual‐level risk factors in observational studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 22, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.04.006 Barker, E. D., Arseneault, L., Brendgen, M., Fontaine, N., & Maughan, B. (2008). Joint development of bullying and victimization in adolescence: Relations to delinquency and self‐harm. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(9), 1030–1038. https:// doi.org/10.1097/CHI.ObO13e31817eec98 Bauer, P. J., Larkina, M., Güler, E., & Burch, M. (2019). Long‐term autobiographical memory across middle childhood: Patterns, predictors, and implications for conceptualizations of childhood amnesia. Memory, 27(9), 1175–1193. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 09658211.2019.1615511 Beltran‐Catalan, M., & Cruz‐Catalan, E. (2020). How long bullying last? A comparison between a self‐reported general bullying‐victimization question and specific bullying‐victimization questions. Children and Youth Services Review, 111, 104844–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. childyouth.2020.104844 Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B. Methodological, 57, 289–300. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x Cénat, J. M., Blais, M., Hébert, M., Lavoie, F., & Guerrier, M. (2015). Correlates of bullying in Quebec high school students: The vulnerability of sexual‐minority youth. Journal of Affective Disorders, 183, 315–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.011 Cornell, D., Klein, J., Konold, T., & Huang, F. (2012). Effects of validity screening items on adolescent survey data. Psychological Assessment, 24(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024824 Cornell, D. G., Lovegrove, P. J., & Baly, M. W. (2014). Invalid survey response patterns among middle school students. Psychological Assessment, 26(1), 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034808 Croucher, S. M., Nguyen, T., & Rahmani, D. (2020). Prejudice toward Asian Americans in the COVID‐19 pandemic: The effects of social media use in the United States. Frontiers in Communication, 5, 39. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00039 Cruz, M. D., Moeurn, T., Files, T., Fadrigon, N., Halbe, M., Schweng, L., & Chan, D. (2020, September, 17). They blamed me because I am Asian: Findings from AAPI youth incidents. Stop AAPI Hate Reports and Releases. https://secureservercdn.net/104.238.69.231/a1w.90d.myftpu pload.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Stop-AAPI-Hate-Youth-Camp aign-Report-9-17.pdf Cunningham, C. E., Cunningham, L. J., Ratcliffe, J., & Vaillancourt, T. (2010). A qualitative analysis of the bullying prevention and intervention recommendations of students in Grades 5 to 8. Journal of School Violence, 9(4), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 15388220.2010.507146 Cunningham, C. E., Mapp, C., Rimas, H., Cunningham, L., Mielko, S., Vaillancourt, T., & Marcus, M. (2016). What limits the effectiveness of antibullying programs? A thematic analysis of the perspective of students. Psychology of Violence, 6(4), 596–606. https://doi.org/10. 1037/a0039984 Dorn, E., Hancock, B., Sarakatsannis, J., & Viruleg, E. (2020). COVID‐19 and student learning in the United States: The hurt could last a lifetime. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/ industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and- student-learning-in-the-united-states-the-hurt-could-last-a-lifetime Dunne, M., Bosumtwi‐Sam, C., Sabates, R., & Owusu, A. (2010). Bullying and school attendance: A case study of senior high school students in Ghana. Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity (CREATE). Brighton, UK. http://www.create-rpc.org/pdf_ documents/PTA41.pdf Education Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. E.2. (1990). https://www.ontario.ca/laws/ statute/90e02 Finn, J. D., Panozzo, G. M., & Achilles, C. M. (2003). The ‘why's' of class size: Student behavior in small classes. Review of educational VAILLANCOURT ET AL. | 567

- 12. research, 73(3), 321–368. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430730 03321 Green, J. G., Oblath, R., Felix, E. D., Furlong, M. J., Holt, M. K., & Sharkey, J. D. (2018). Initial evidence for the validity of the California Bullying Victimization Scale (CBVS‐R) as a retrospective measure for adults. Psychological Assessment, 30(11), 1444–1453. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000592 Gover, A. R., Harper, S. B., & Langton, L. (2020). Anti‐Asian hate crime during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Exploring the reproduction of inequality. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 647–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09545-1 Haltigan, J. D., & Vaillancourt, T. (2014). Joint trajectories of bullying and peer victimization across elementary and middle school and associations with symptoms of psychopathology. Developmental Psychology, 50(11), 2426–2436. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038030 Haltigan, J. D., & Vaillancourt, T. (2018). The influence of static and dynamic intrapersonal factors on longitudinal patterns of peer victimization through mid‐adolescence: A latent transition analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(1), 11–26. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10802-017-0342-1 Humphrey, T., & Vaillancourt, T. (2020). Longitudinal relations between bullying perpetration, sexual harassment, homophobic taunting, and dating violence: Evidence of heterotypic continuity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(10), 1976–1986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020- 01307-w Hutzell, K. L., & Payne, A. A. (2012). The impact of bullying victimization on school avoidance. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 10(4), 370–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204012438926 Khoury‐Kassabri, M., Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., & Zeira, A. (2004). The contributions of community, family, and school variables to student victimization. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34(3‐4), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-004-7414-4 Kundu, A., Bej, T., & Rice, M. (2021). Time to engage: Implementing math and literacy blended learning routines in an Indian elementary classroom. Education and Information Technologies, 26(1), 1201–1220. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10639-020-10306-0 Macaruso, P., Wilkes, S., & Prescott, J. E. (2020). An investigation of blended learning to support reading instruction in elementary schools. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(6), 2839–2852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09785-2 Marques de Miranda, D., da Silva Athanasio, B., Sena Oliveira, A. C., & Simoes‐ e‐Silva, A. C. (2020). How is COVID‐19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51, 101845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101845 McDougall, P., & Vaillancourt, T. (2015). Long‐term adult outcomes of peer victimization in childhood and adolescence: Pathways to adjustment and maladjustment. American Psychologist, 70(4), 300–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039174 Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., & Baki, M. (2013). The effectiveness of online and blended learning: A meta‐analysis of the empirical literature. Teachers College Record, 115(3), 1–47. Mennicke, A., Bush, H. M., Brancato, C., & Coker, A. L. (2020). Sexual minority high school boys' and girls' risk of sexual harassment, sexual violence, stalking, and bullying. Violence against women, 27, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801220937811 Ministry of Education (2020, December 24th). COVID‐19: Reopening schools. https://www.ontario.ca/page/covid-19-reopening-schools Molcho, M., Craig, W., Due, P., Pickett, W., Harel‐Fisch, Y., & Overpeck, M. (2009). Cross‐national time trends in bullying behaviour 1994–2006: Findings from Europe and North America. International Journal of Public Health, 54(2), 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-5414-8 Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., & Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7(1), 60–76. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60 Nakamoto, J., & Schwartz, D. (2010). Is peer victimization associated with academic achievement? A meta‐analytic review. Social Development, 19(2), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00539.x National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Preventing Bullying Through Science, Policy, and Practice. The National Academies Press. Nye, B., Hedges, L. V., & Konstantopoulos, S. (2000). The effects of small classes on academic achievement: The results of the Tennessee class size experiment. American Educational Research Journal, 37(1), 123–151. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163474 Nylund, K., Bellmore, A., Nishina, A., & Graham, S. (2007). Subtypes, severity, and structural stability of peer victimization: What does latent class analysis say? Child Development, 78(6), 1706–1722. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01097.x Olweus, D. (1993). Victimization by peers: Antecedents and long‐term outcomes. In K. H. Rubin, & J. B. Asendorf (Eds.), Social withdrawal, inhibition, and shyness (pp. 315–341). Erlbaum. Olweus, D. (1994). Bullying at school: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35(7), 1171–1190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610. 1994.tb01229.x Pepler, D., & Bierman, K. (2018). With a little help from my friends: The importance of peer relationships for social‐emotional development. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Social Emotional Learning Briefs, Pennsylvania State University. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/ 2018/11/with-a-little-help-from-my-friends–the-importance-of-peer-rel ationships-for-social-emotional-development.html Peterson, C. (2002). Children's long‐term memory for autobiographical events. Developmental Review, 22(3), 370–402. Peterson, C., Morris, G., Baker‐Ward, L., & Flynn, S. (2014). Predicting which childhood memories persist: Contributions of memory characteristics. Developmental Psychology, 50(2), 439–448. https:// doi.org/10.1037/a0033221 Phelps, C., & Sperry, L. L. (2020). Children and the COVID‐19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S73–S75. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000861 Rivers, I. (2001). Retrospective reports of school bullying: Stability of recall and its implications for research. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 19(1), 129–141. Schwartz, D., Gorman, A. H., Nakamoto, J., & Toblin, R. L. (2005). Victimization in the peer group and children's academic functioning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(3), 425–435. https://doi.org/10. 1037/0022-0663.97.3.425 Spears, B., Slee, P., Campbell, M., & Cross, D. (2011). Educational change and youth voice: Informing school action on cyberbullying. Centre for Strategic Education, Seminar Series (208), 1–15. https://eprints.qut. edu.au/47239/ Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education. Ttofi, M. M., Farrington, D. P., & Lösel, F. (2012). School bullying as a predictor of violence later in life: A systematic review and meta‐ analysis of prospective longitudinal studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(5), 405–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012. 05.002 Ttofi, M. M., Farrington, D. P., Lösel, F., & Loeber, R. (2011). The predictive efficiency of school bullying versus later offending: A systematic/ meta‐analytic review of longitudinal studies. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 21(2), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.808 Turner, S., Taillieu, T., Fortier, J., Salmon, S., Cheung, K., & Afifi, T. O. (2018). Bullying victimization and illicit drug use among students in Grades 7 to 12 in Manitoba, Canada: A cross‐sectional analysis. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 109(2), 183–194. https://doi.org/ 10.17269/s41997-018-0030-0 UNICEF. (2019). Annual Report. For Every Child. https://www.unicef.org/ reports/annual-report-2019 568 | VAILLANCOURT ET AL.

- 13. UNICEF. (2020). Worlds Apart: Canadian Companion to UNICEF Report Card 16. https://oneyouth.unicef.ca/sites/default/files/2020-09/UNICEF%20 RC16%20Canadian%20Companion%20EN_Web.pdf Vaillancourt, T., Brittain, H., Bennett, L., Arnocky, S., McDougall, P., Hymel, S., Short, K., Sunderani, S., Scott, C., Mackenzie, M., & Cunningham, L. (2010). Places to avoid: Population-based study of student reports of unsafe and high bullying areas at school. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 25(1), 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0829573509358686 Vaillancourt, T., McDougall, P., Hymel, S., Krygsman, A., Miller, J., Stiver, K., & Davis, C. (2008). Bullying: Are researchers and children/ youth talking about the same thing? International Journal of Behavioral Development: IJBD, 32(6), 486–495. https://doi.org/10. 1177/0165025408095553 Vaillancourt, T., & Palamarchuk, I. (2021). Neurobiological factors of bullying victimization. In P. K. Smith & J. O'Higgins Norman (Eds.) Wiley‐Blackwell bullying handbook. Vaillancourt, T., Trinh, V., McDougall, P., Duku, E., Cunningham, L., Cunningham, C., Hymel, S., & Short, K. (2010). Optimizing population screening of bullying in school‐aged children. Journal of School Violence, 9(3), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2010. 483182 van Verseveld, M. D., Fukkink, R. G., Fekkes, M., & Oostdam, R. J. (2019). Effects of antibullying programs on teachers' interventions in bullying situations. A meta‐analysis. Psychology in the Schools, 56(9), 1522–1539. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22283 Vitoroulis, I., & Vaillancourt, T. (2015). Meta‐analytic results of ethnic group differences in peer victimization. Aggressive Behavior, 41(2), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21564 Wolke, D., & Lereya, S. T. (2015). Long‐term effects of bullying. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 100(9), 879–885. https://doi.org/10.1136/ archdischild-2014-306667 Yang, X., Harrison, P., Huang, J., Liu, Y., & Zahn, R. (2021). The impact of COVID‐19‐related lockdown on adolescent mental health in China: A prospective study. Available at SSRN3792956. Yourtown. (2021). Kids Helpline 2020 Insights Report: National Statistical Overview. https://www.yourtown.com.au/sites/default/files/document/ 2020%20Insights%20Kids%20Helpline.pdf Zych, I., Viejo, C., Vila, E., & Farrington, D. P. (2019). School bullying and dating violence in adolescents: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 22, 397–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1524838019854460 How to cite this article: Vaillancourt, T., Brittain, H., Krygsman, A., Farrell, A. H., Landon, S., & Pepler, D. (2021). School bullying before and during COVID‐19: Results from a population‐based randomized design. Aggressive Behavior, 47, 557–569. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21986 VAILLANCOURT ET AL. | 569