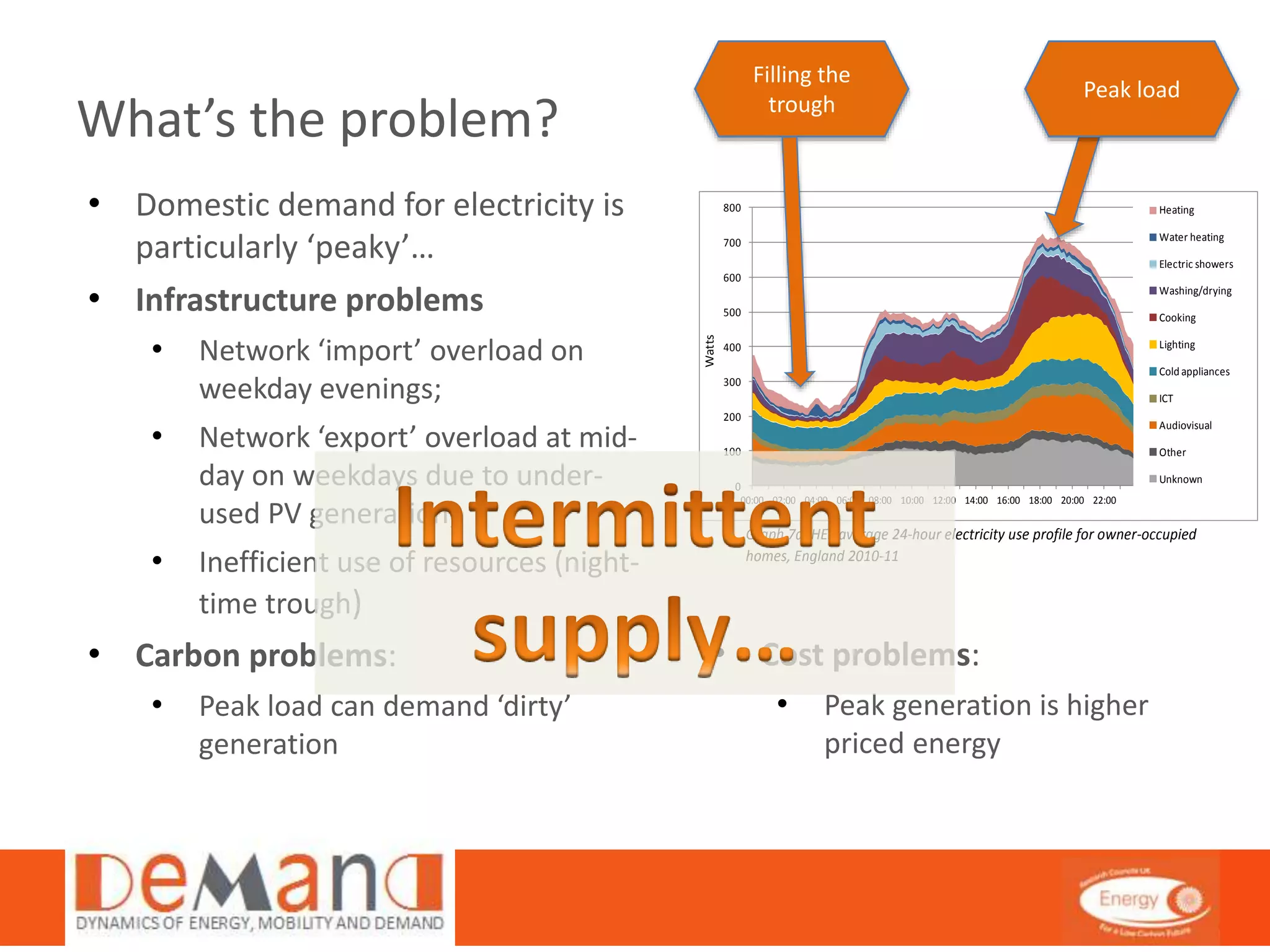

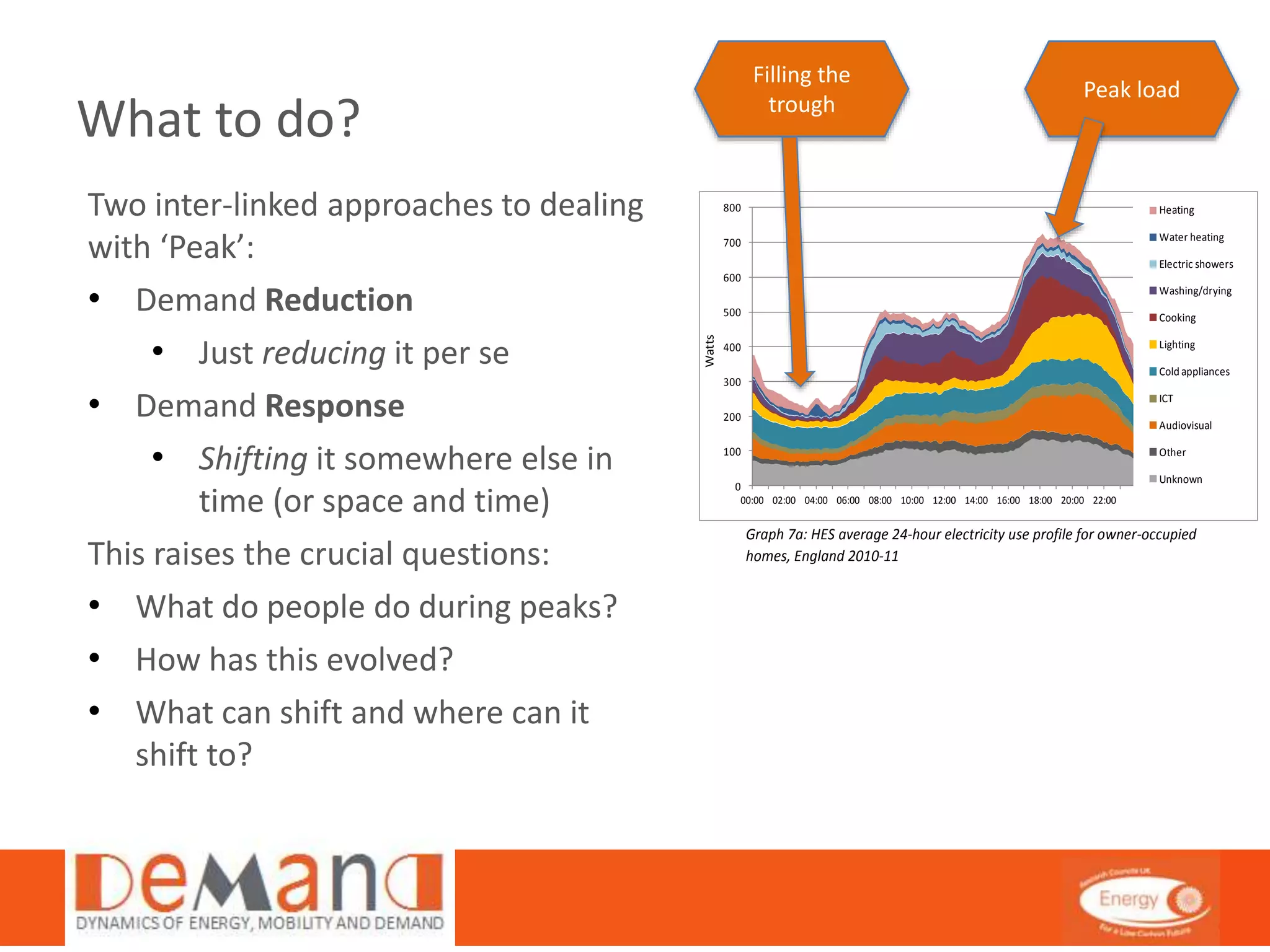

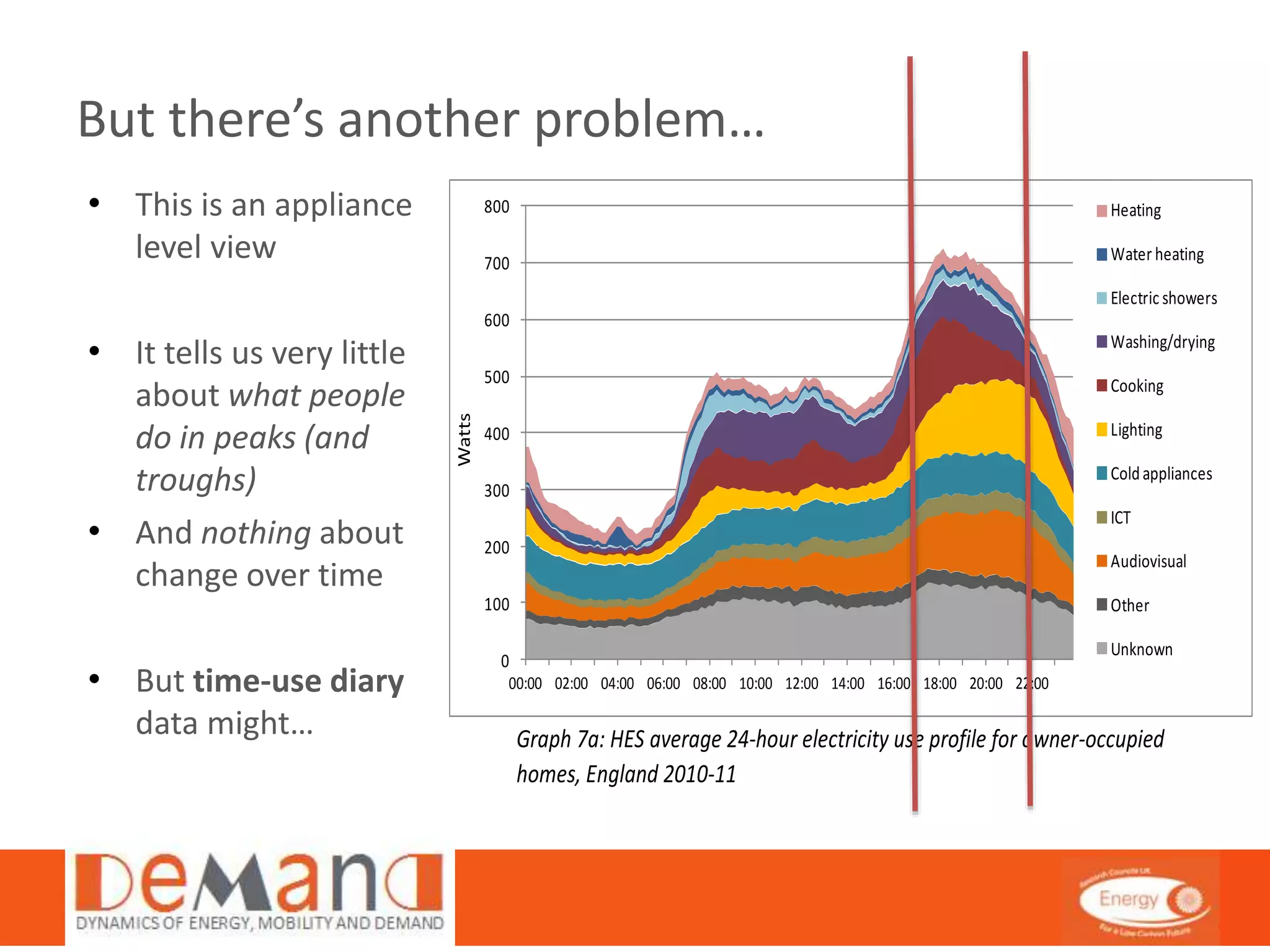

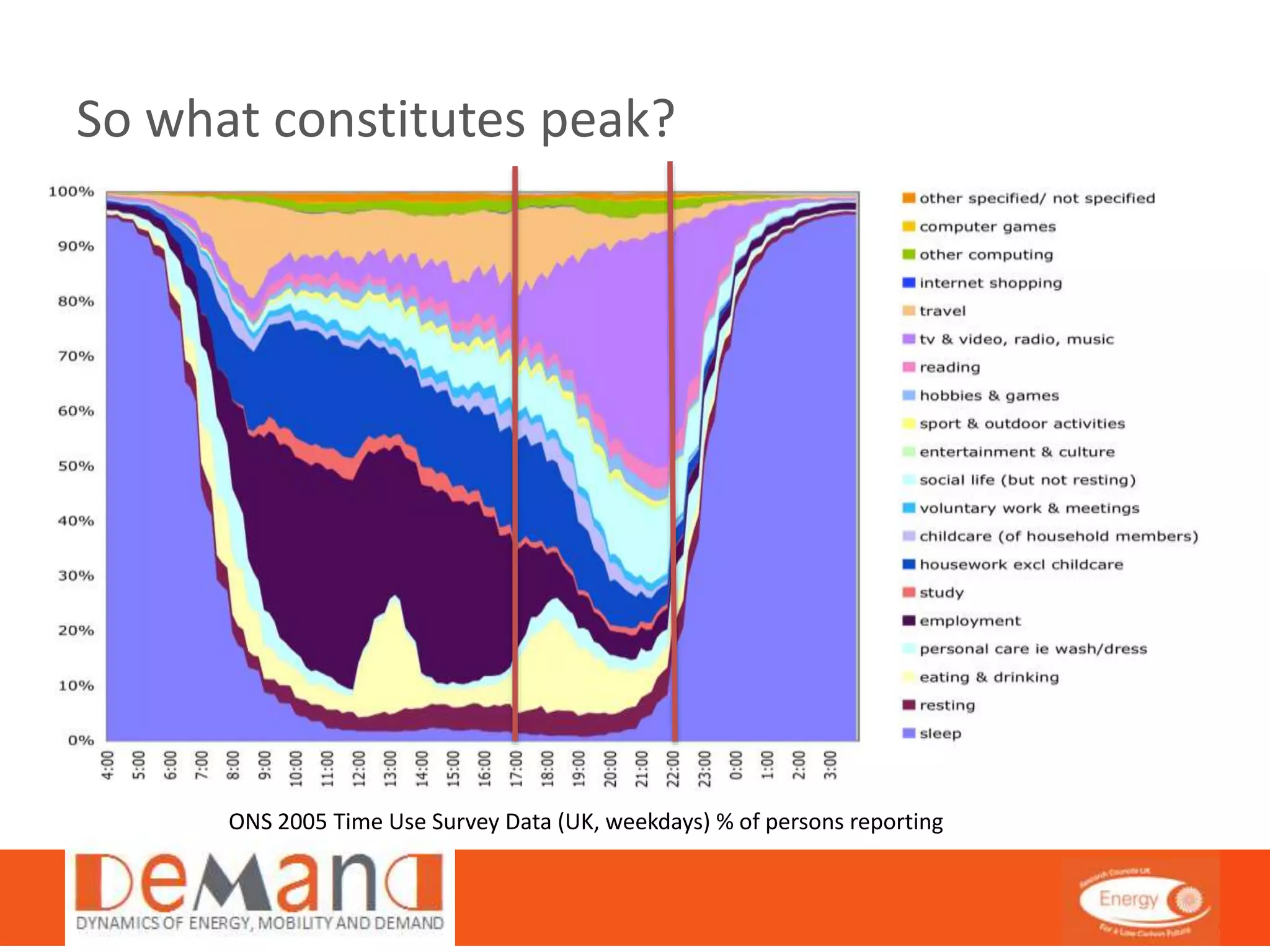

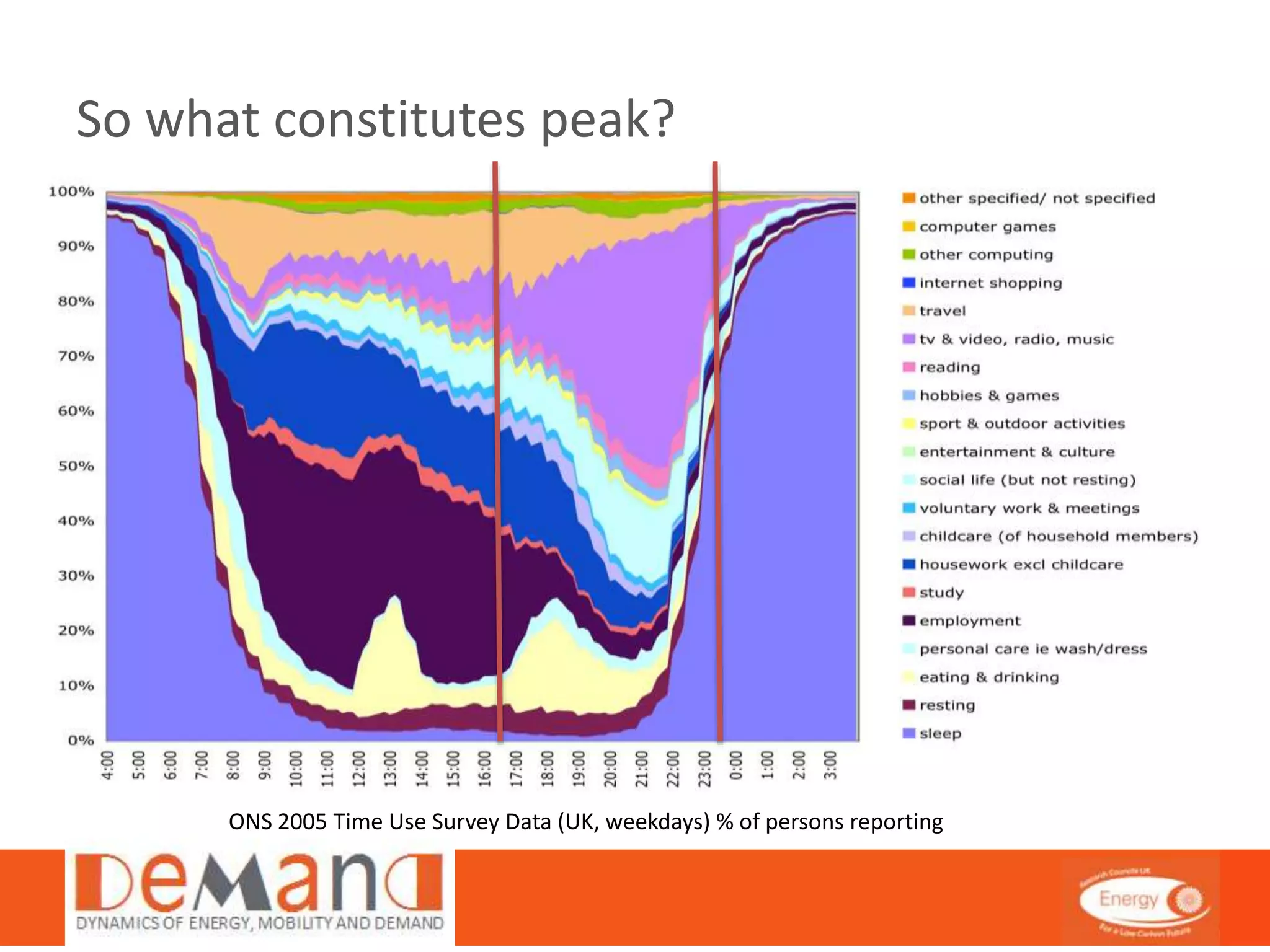

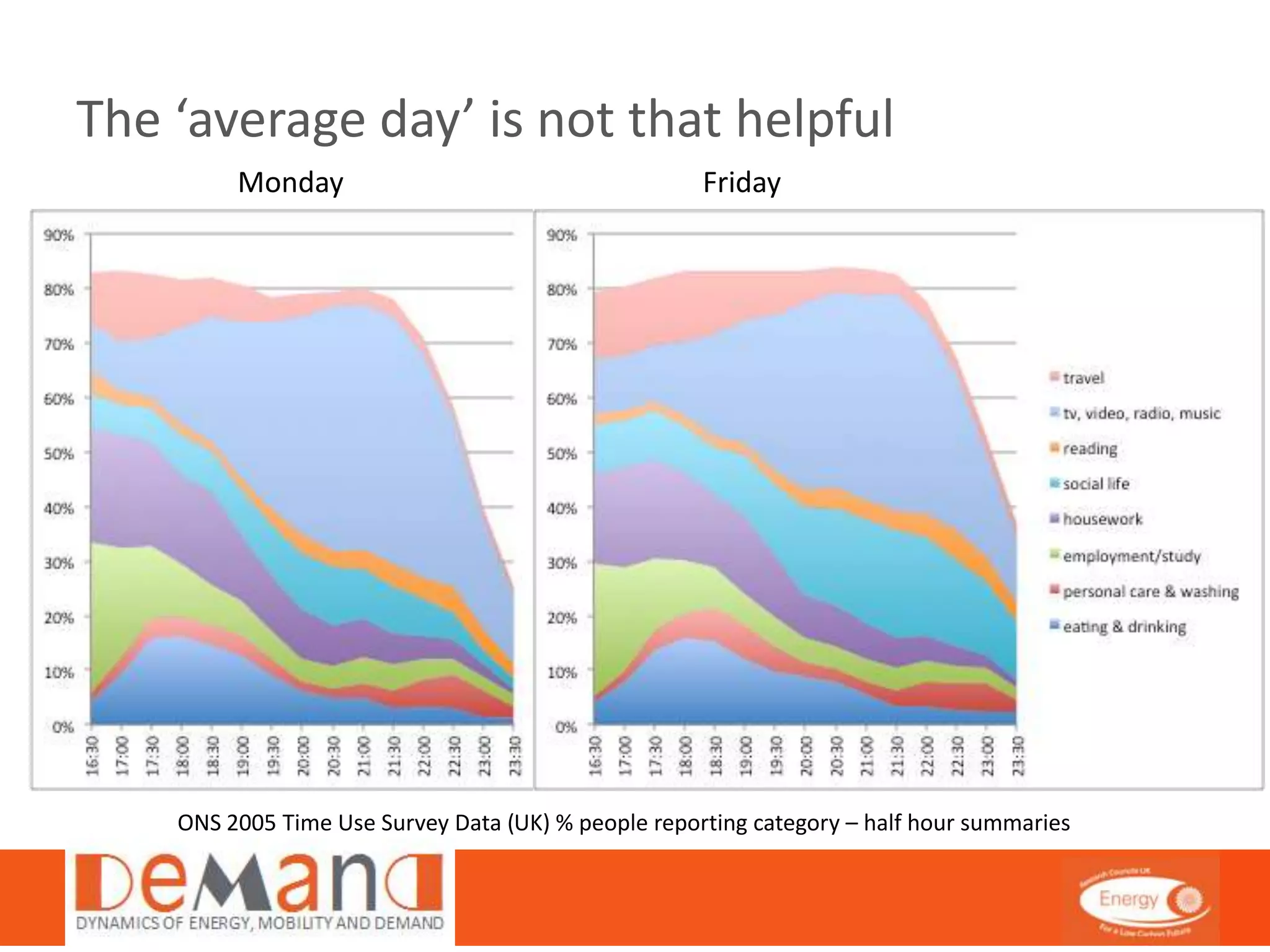

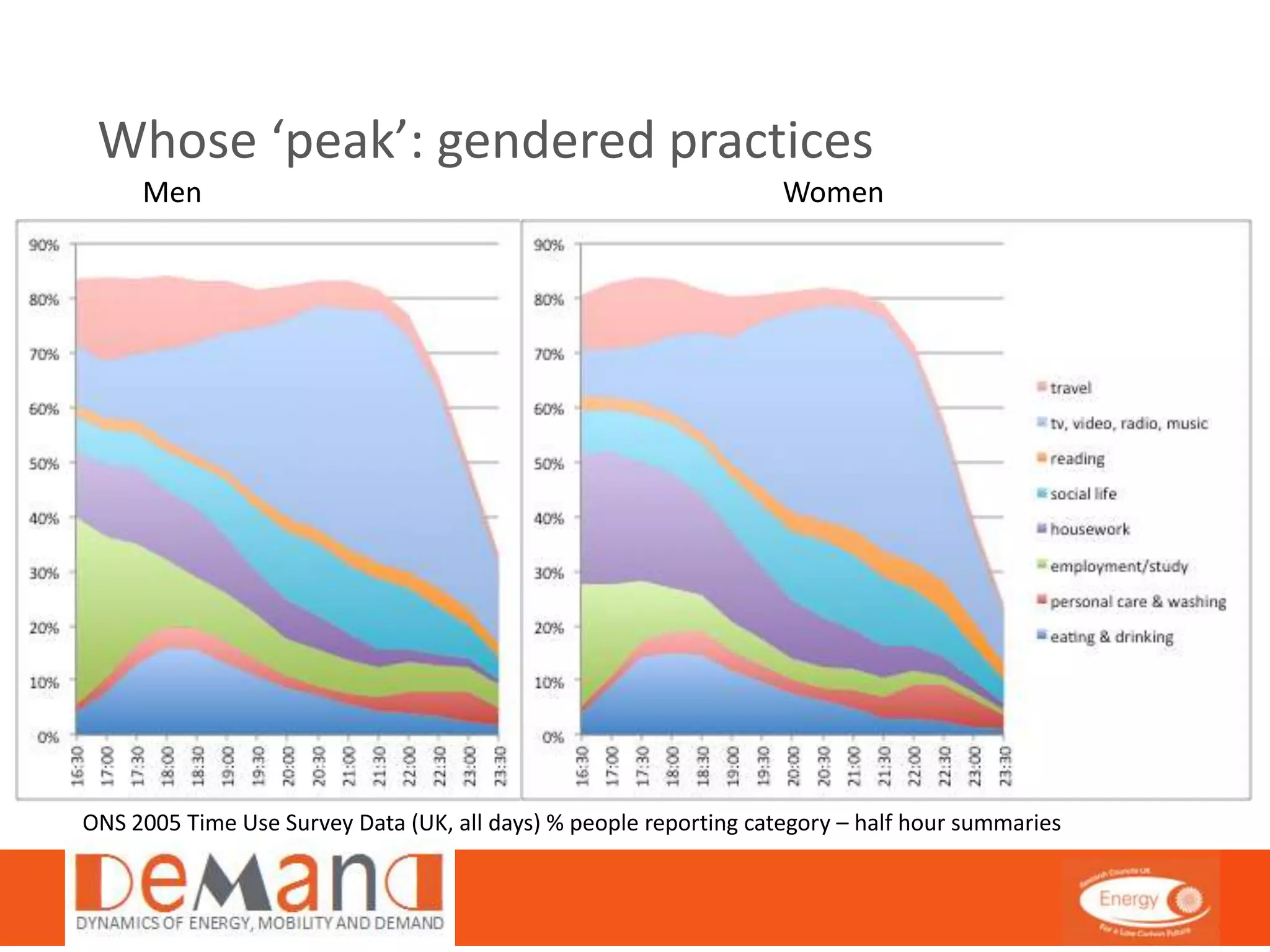

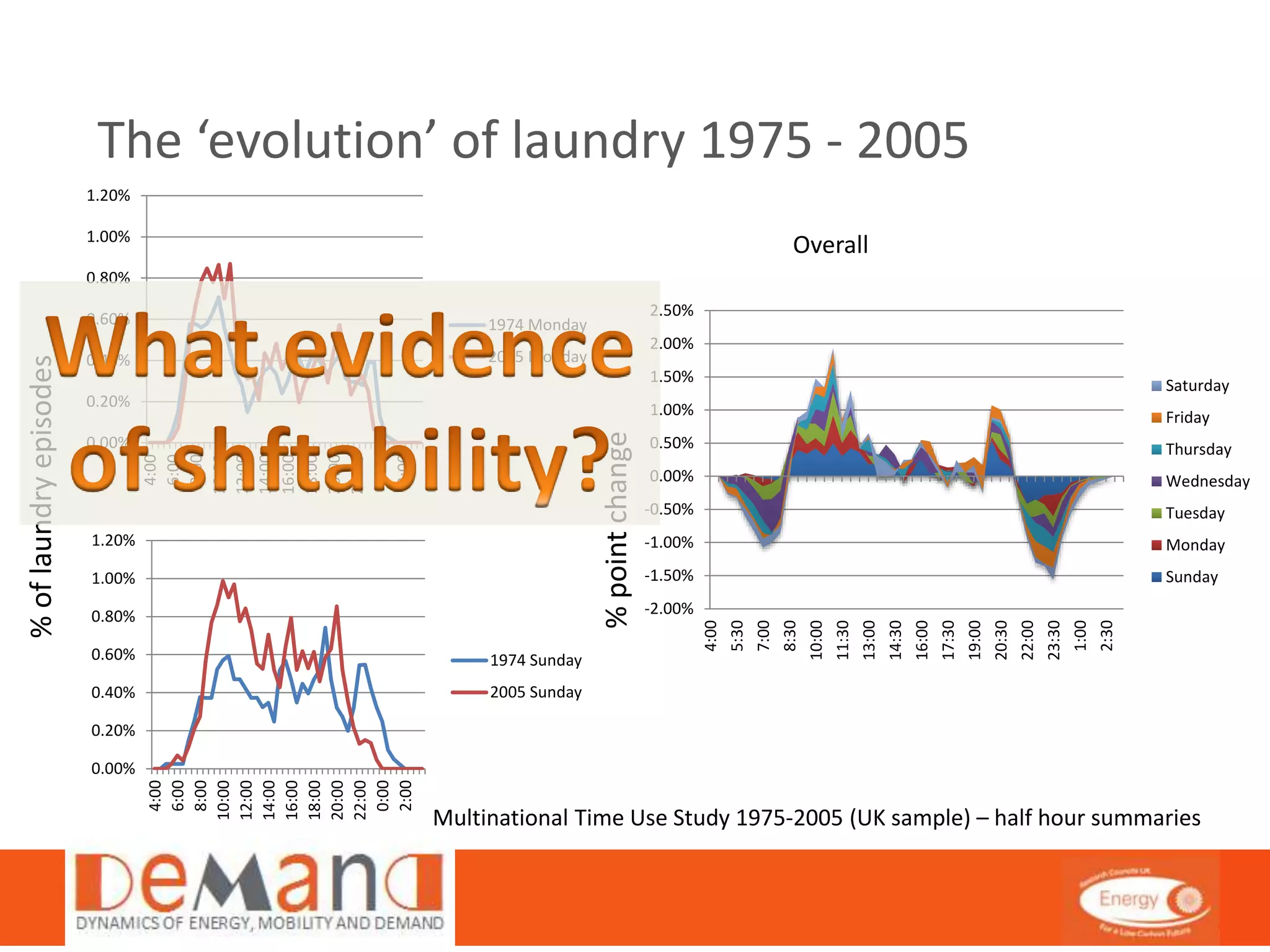

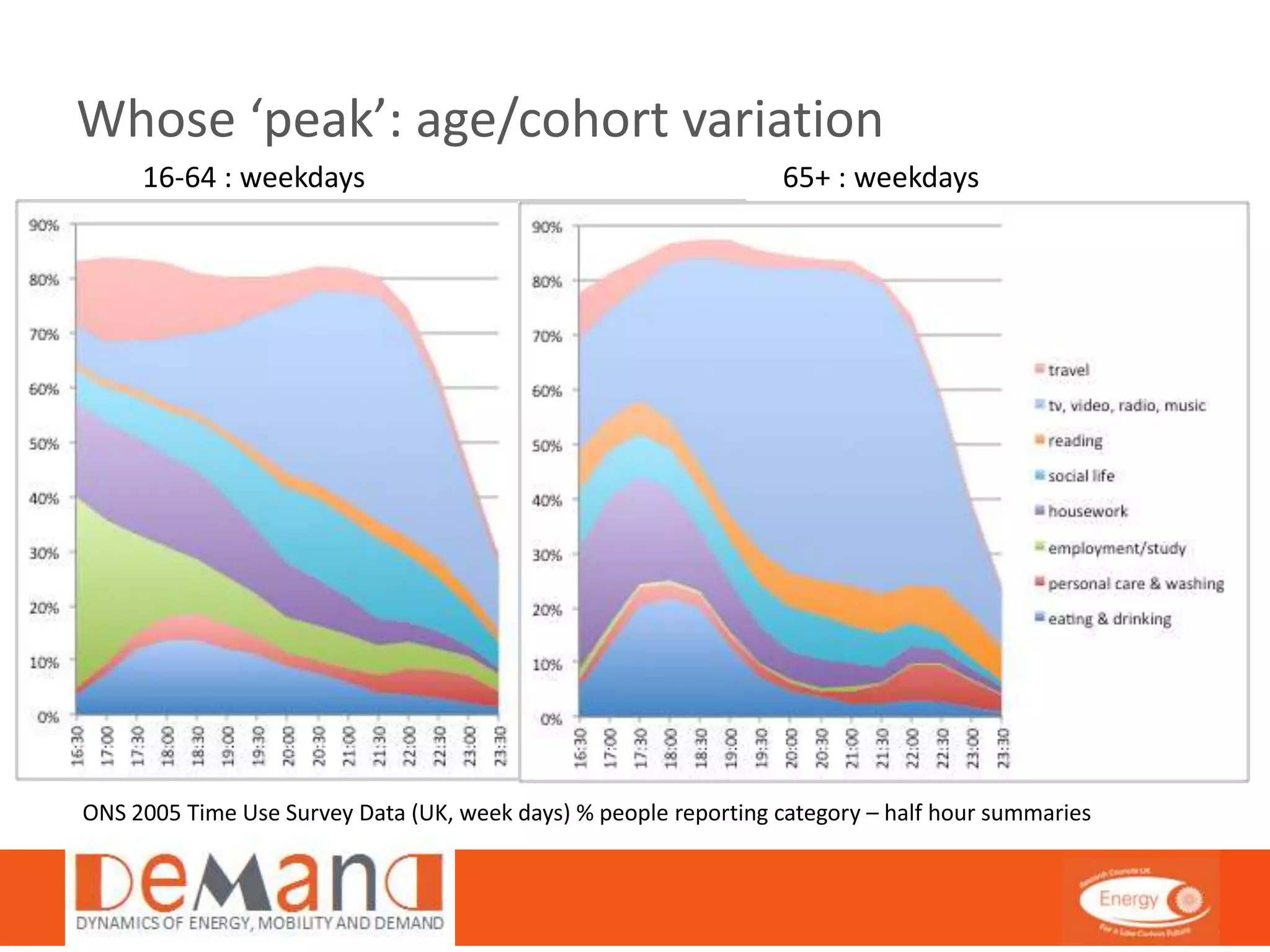

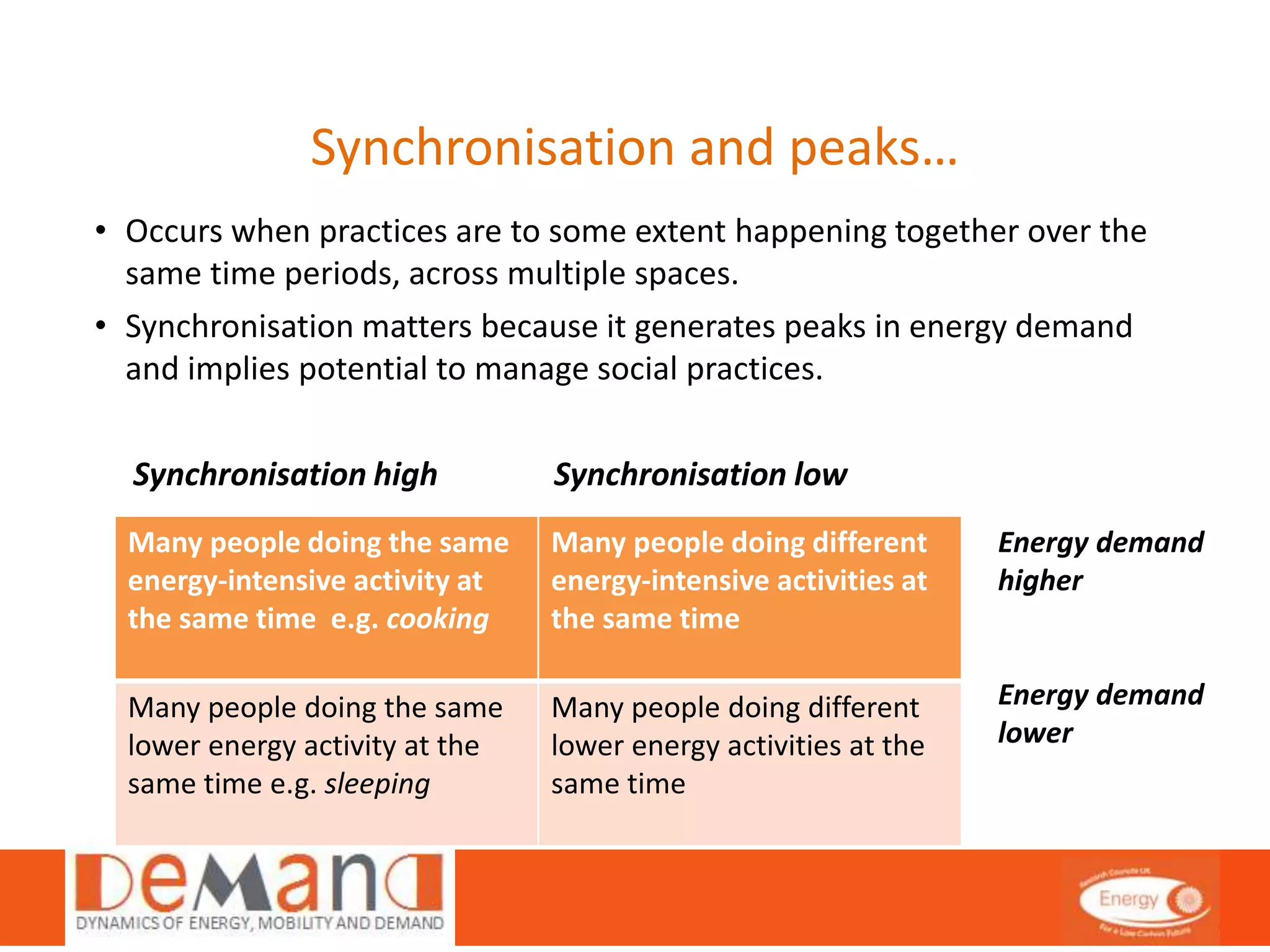

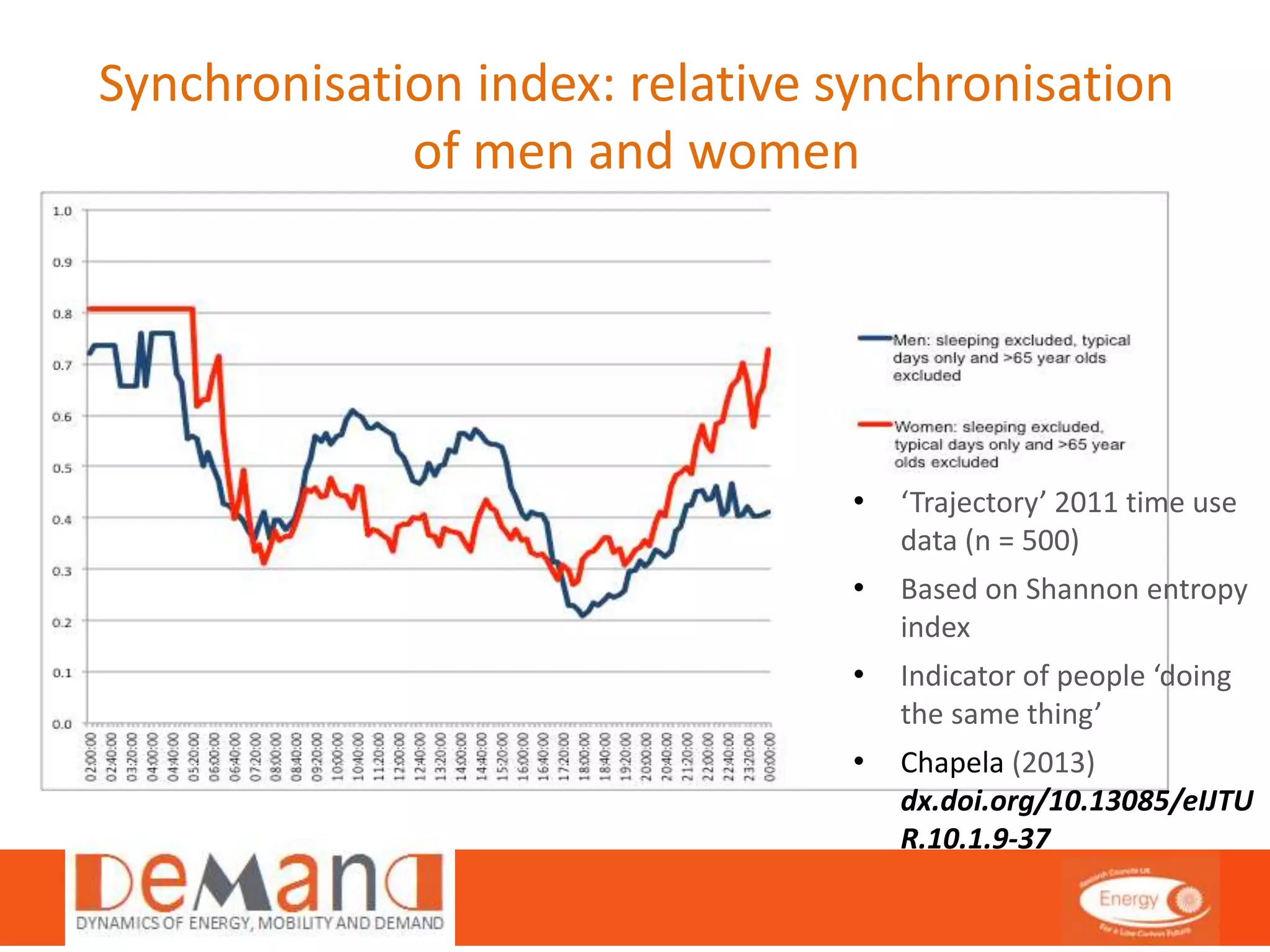

The document discusses the complexities of peak energy demand in the UK, highlighting issues related to domestic electricity consumption patterns and infrastructure limitations. It emphasizes the need for understanding consumer behaviors and social practices that contribute to peak loads and examines potential strategies for demand reduction and response. The authors propose further research to illuminate the social dynamics involved in energy usage and their implications for energy policy.