The performance of institutions such as colleges and schools are of increasing interest to funders and stakeholders because they require accurate estimates of success rates and retention rates. However it is important that the information these estimates are based upon is consistently applied on a like-with-like basis. Students who attend different institutions do not have the same background characteristics and if this isn’t taken into account certain institutions may be misplaced in terms of performance.

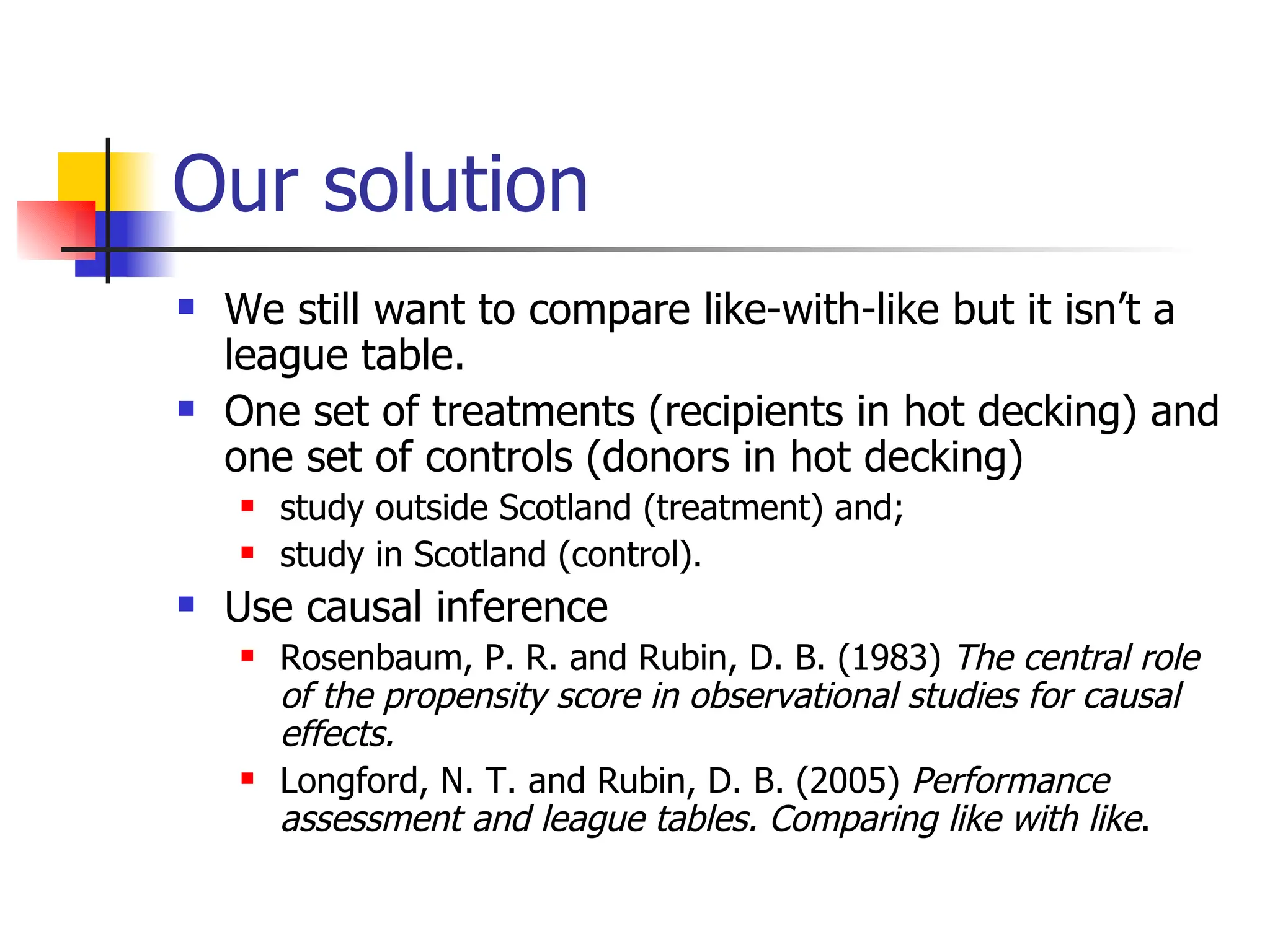

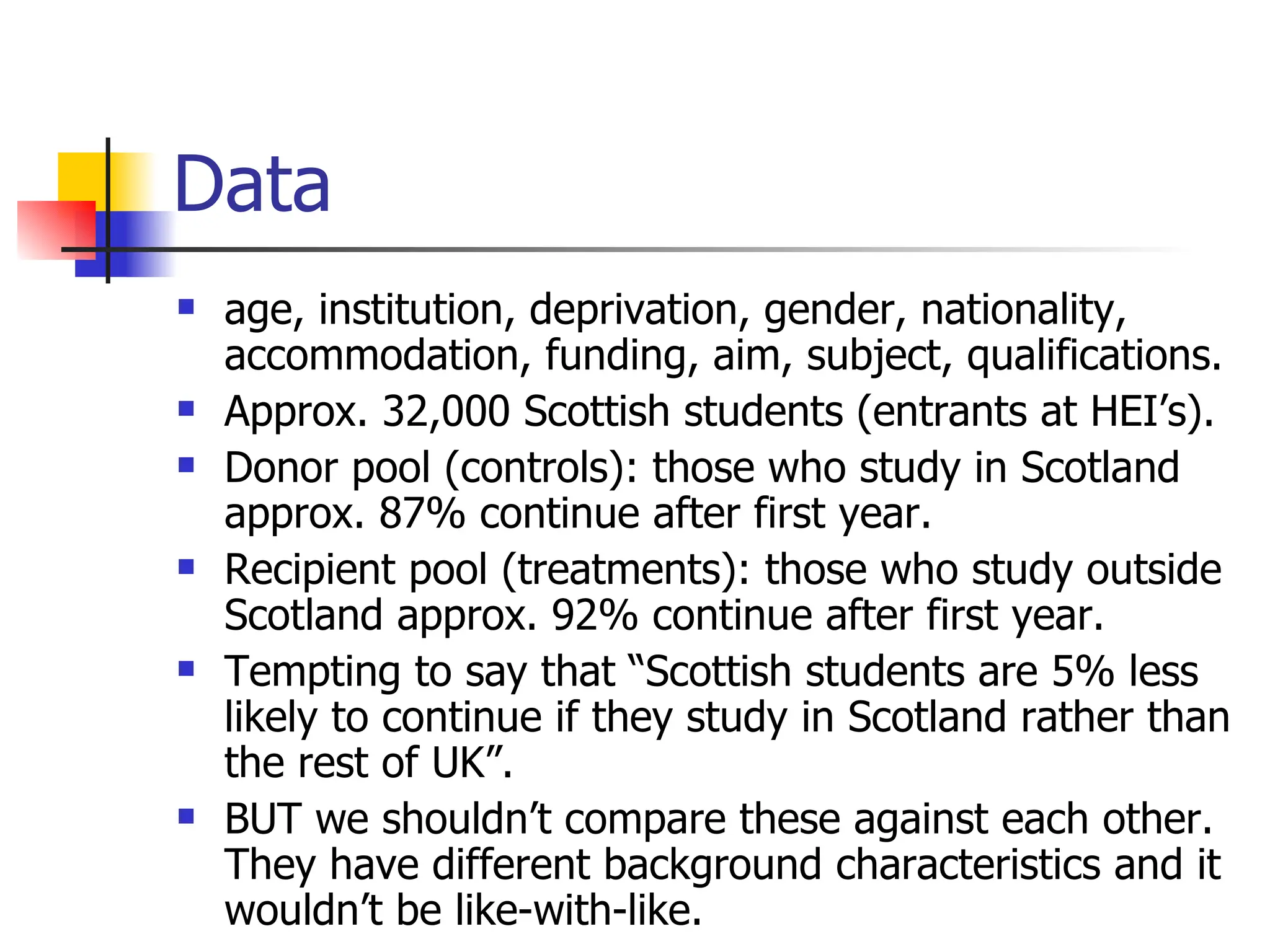

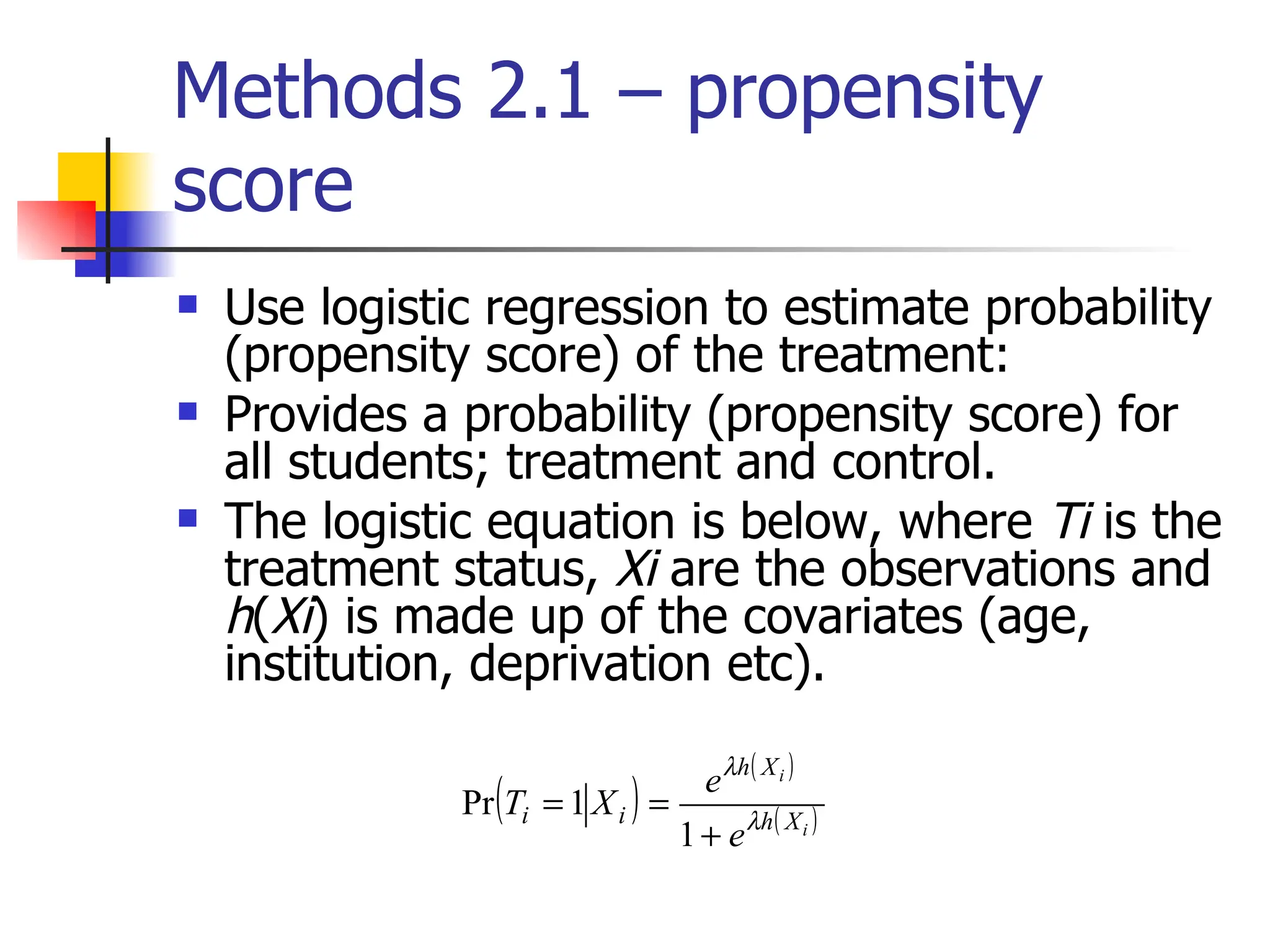

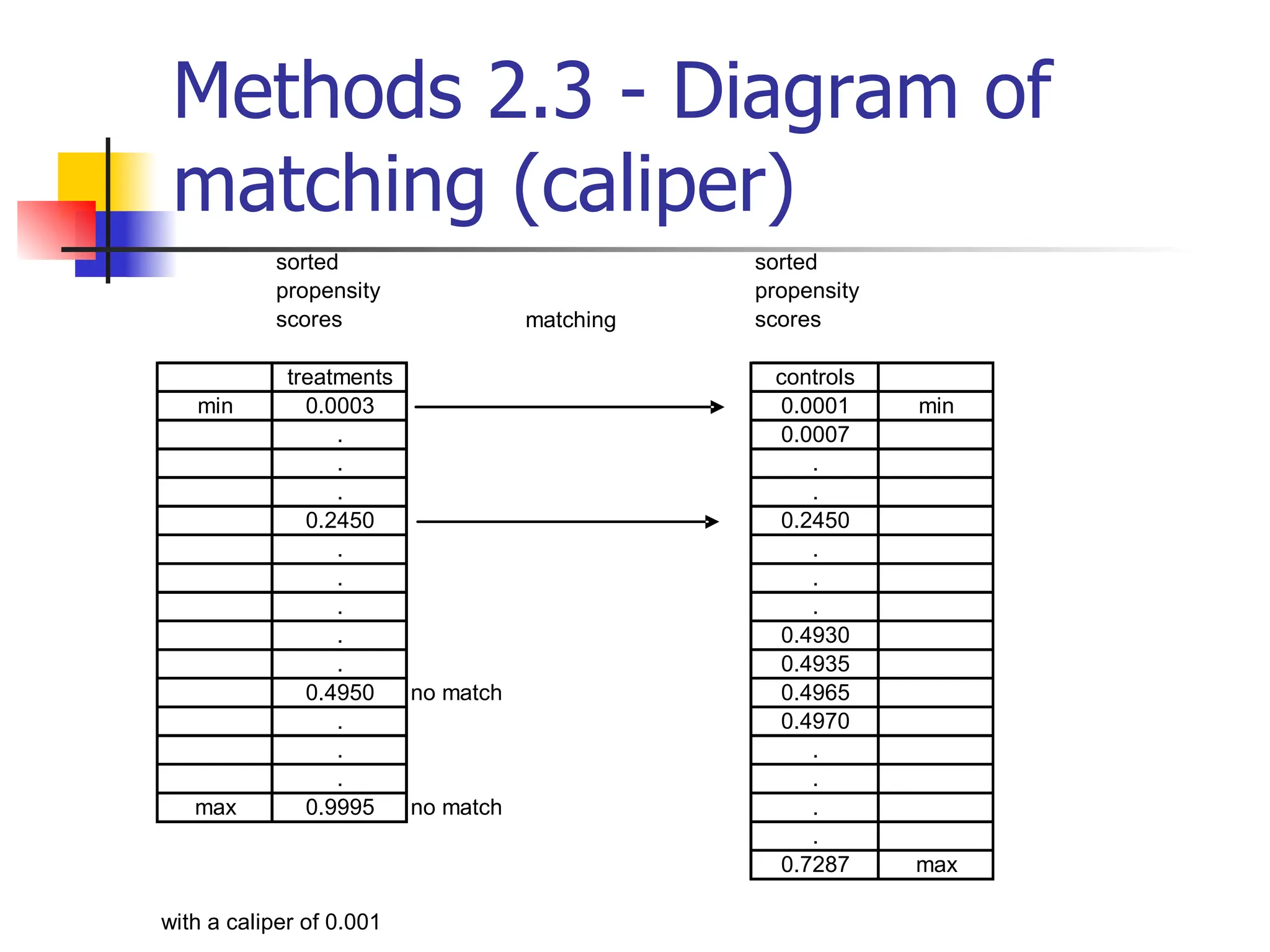

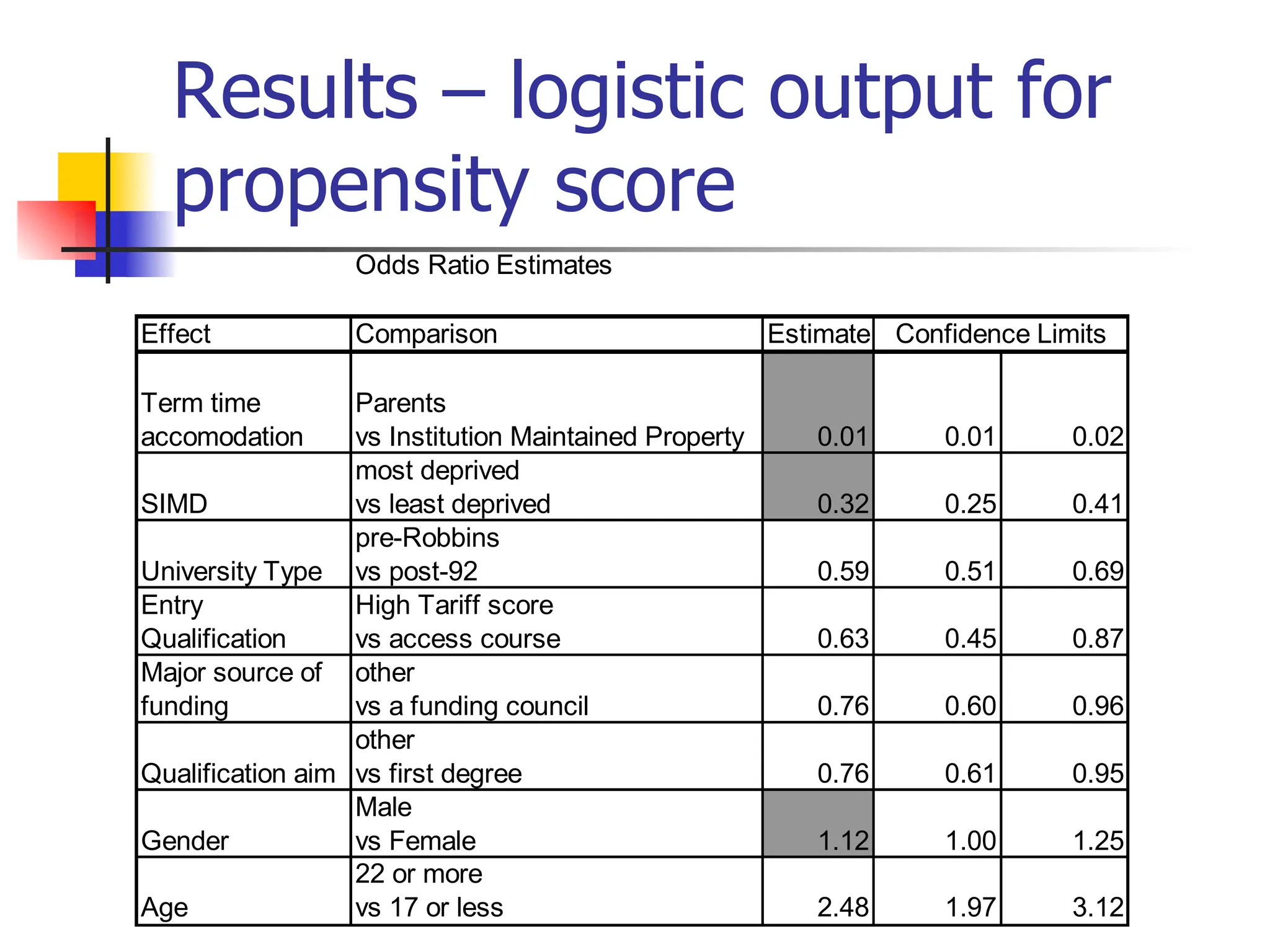

This study uses the technique of causal inference and employs the methods of hot-decking and propensity score matching since these methods can provide a true like-with-like comparison. The study compares the retention rates of Scottish entrants who studied at non-Scottish higher education institutions (HEI’s) against the retention rates of Scottish entrants who studied at Scottish HEI’s.

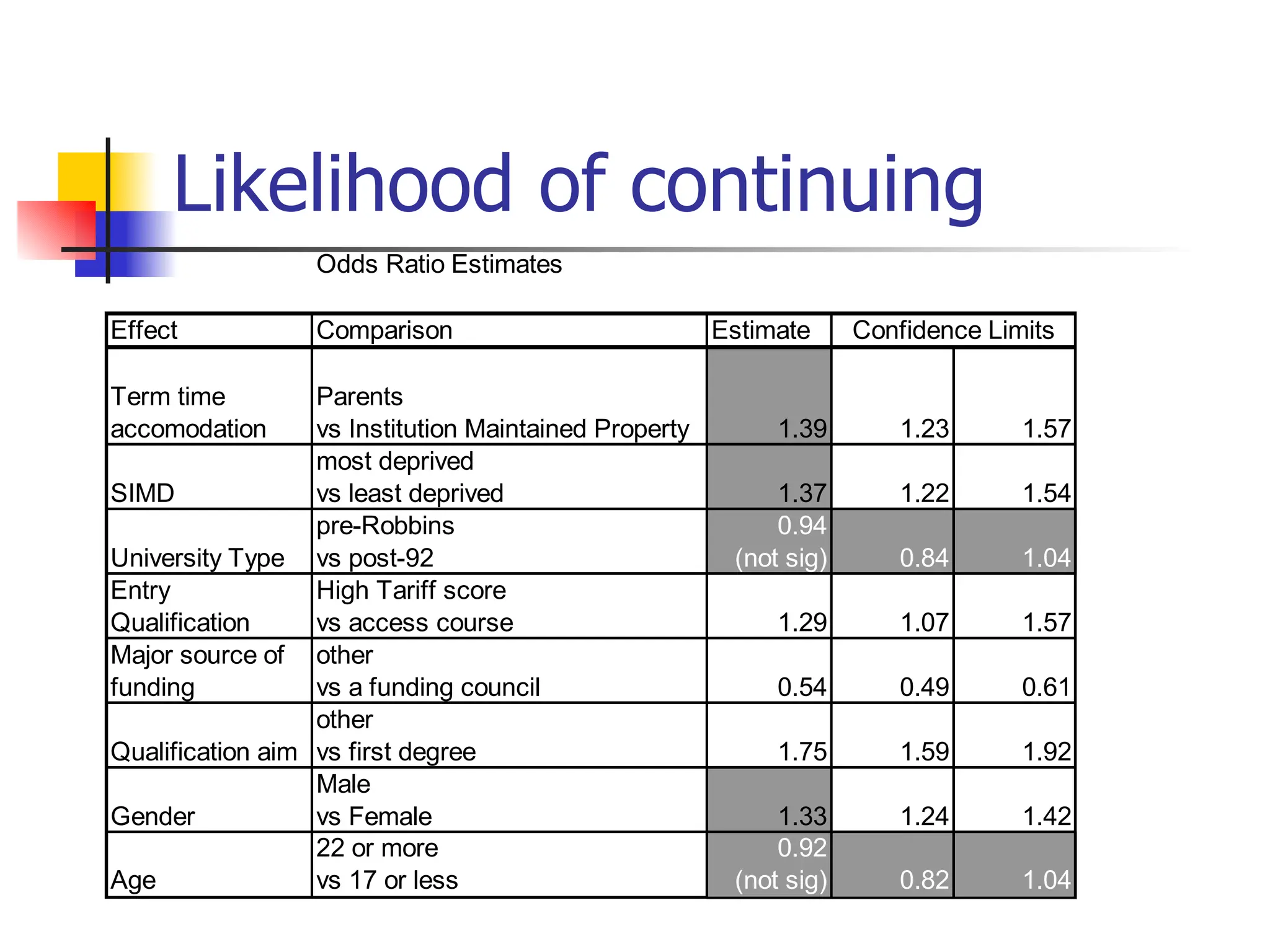

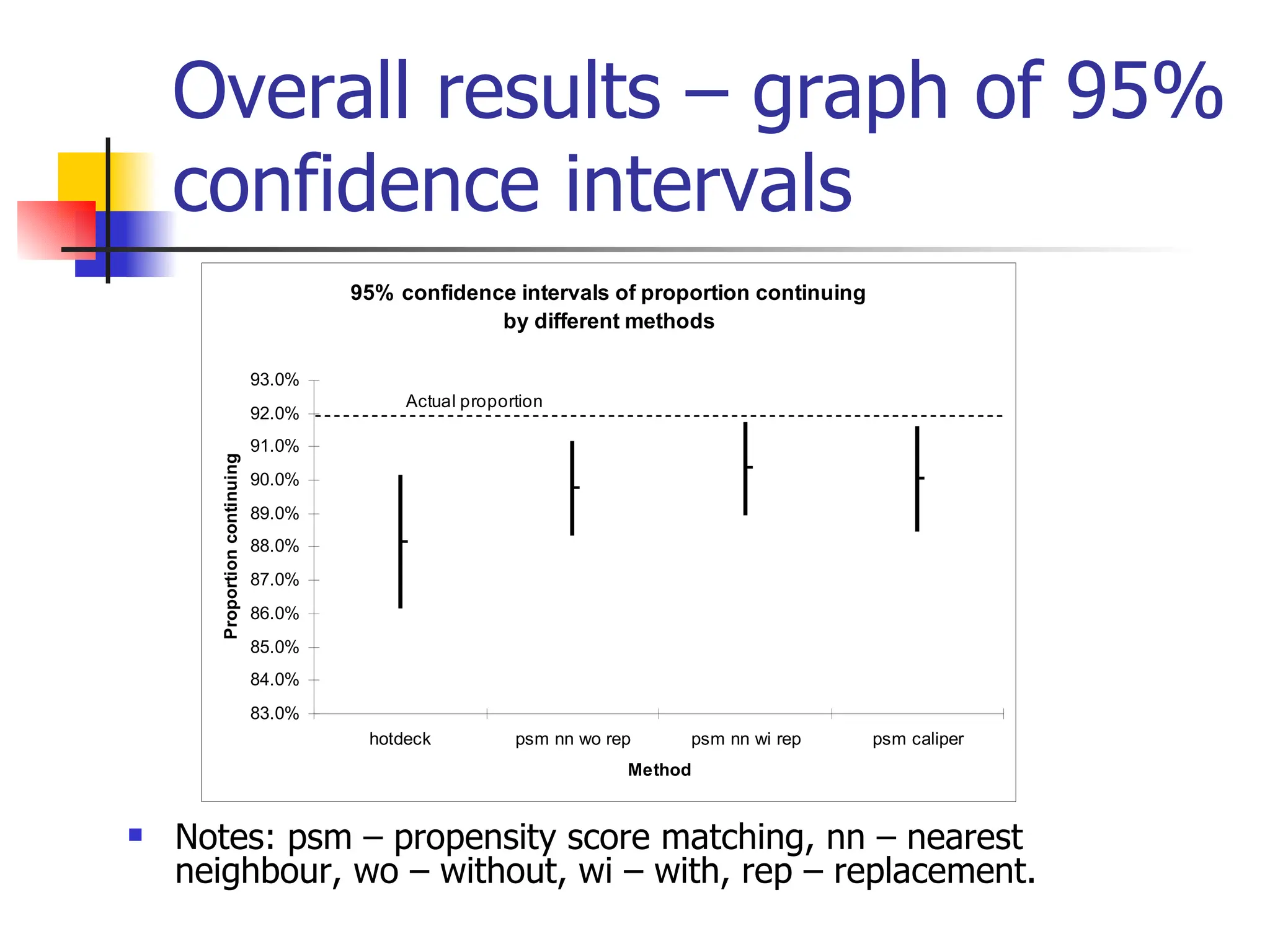

A basic method, which didn’t take account of background characteristics, came to the following conclusion: if those entrants who studied outside Scotland had studied in Scotland they would have been 5% more likely to drop out of their studies. However, the methods of hot-decking and propensity score matching, which perform a true like-with-like comparison, came to the conclusion that the difference in drop-out was less than the 5% quoted by the basic method. Hot-decking provided an estimate of 2% and propensity score matching provided an estimate of 4%.

Further work is required to assess the sensitivity of the results to the assumptions employed in the models. However, the estimates from this causal inference study help to provide an understanding of the impact of different background characteristics upon the performance of institutions.