Song of the desert road | News | National

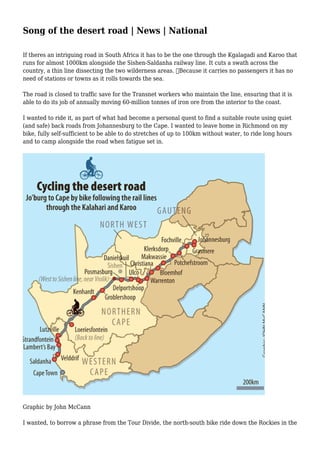

- 1. Song of the desert road | News | National If theres an intriguing road in South Africa it has to be the one through the Kgalagadi and Karoo that runs for almost 1000km alongside the Sishen-Saldanha railway line. It cuts a swath across the country, a thin line dissecting the two wilderness areas. Because it carries no passengers it has no need of stations or towns as it rolls towards the sea. The road is closed to traffic save for the Transnet workers who maintain the line, ensuring that it is able to do its job of annually moving 60-million tonnes of iron ore from the interior to the coast. I wanted to ride it, as part of what had become a personal quest to find a suitable route using quiet (and safe) back roads from Johannesburg to the Cape. I wanted to leave home in Richmond on my bike, fully self-sufficient to be able to do stretches of up to 100km without water, to ride long hours and to camp alongside the road when fatigue set in. Graphic by John McCann I wanted, to borrow a phrase from the Tour Divide, the north-south bike ride down the Rockies in the

- 2. United States, to do no more than Eat Sleep Ride. I have on previous rides slept out on occasion, but for this one I wanted to do the whole thing outside. Like the dirt-bag riders at the front end of the Tour Divide who eschew formal accommodation, I would camp out to get further each day before stopping to sleep. This is free riding, reminiscent perhaps of hobo life described by Jack London in The Road. London, who died in 1916, was given recent prominence because his Call of the Wild inspired Alexander Supertramp Christopher McCandless to go into the wilderness where he met an untimely end. Like Anne Mustoe, I would ride as a vagabond. Mustoe was a successful school headmistress at a British school when she looked out of a bus window in Turkey and saw a man on a bicycle. She quit her job and cycled around the world twice, writing two books and enduring opprobrium for rejecting respectability in favour of vagabonding. This tradition also owes much to Irish writer Dervla Murphy, who, with a bike and an abundance of attitude, looked the world foursquare in the eye and then rode it. So enchanted had I become with the idea of vagabonding that I bizarrely found myself wistfully looking at homeless people in Johannesburg, wondering, enviously, where they would be bedding down for the night. But then, perhaps, homeless envy is not that weird. There has just been a sleep-out in Johannesburg for chief executives when they paid R100000 to be supplied with nothing more than a mug of soup and a cardboard box, this being part of a worldwide initiative to raise funds and draw attention to the plight of the homeless. But, to temper romance with accuracy, it should be understood that when you leave home today on a cycling adventure such as I planned, you carry lashings of high-tech gear to ease the inconvenience of dirt-bag life. I had sufficient warm clothes to be able to cope at several degrees below zero, as well as rain gear, a sleeping bag and bivy (a waterproof enclosure for the sleeping bag) and a blow-up mattress to put distance between myself and the freezing ground. I had capacity to carry four litres of liquid, tools and some basic spares, a map, a bag of food and electronics such as two cellphones (one MTN, one Vodacom). Packing, the night before, had taken several attempts before I was able to squeeze everything into three bags, one under the handle bars, the other underneath the seat, with the lighter stuff in my backpack. My bike is kitted with an electrical system supplied by a friend, Graham Bate. It uses a dynamo on the front hub to run a light or charge a battery that powers a back-up light and can be used to recharge the cellphones. My route would aim to get me out of Jozi on roads as car-free as I could find and then ride service roads along the main railway line as far as Warrenton on the Vaal River, before heading west via Postmasburg to the Sishen line. Big-sky country

- 3. From there I would be following in the tyre tracks of Prince Albert-based Johann Rissik, a cycling nut who was the first to ride the Sishen line, back in 2008. He described it as bipolar: Left is high-tech, man-made heavy industrial wilderness. Right is the open veld, a lot of open veld in fact. Its all big- sky country. Johann advised doing the ride in autumn, winter or spring. Not summer. There will always be someone who has to try it in summer. If you die doing it, you could spoil it for others, he wrote, laying down a code of conduct on his blog for others who wanted to do it. I left home at 6am. It was midwinter and chilly. The first part of my ride, the hill up past the SABC into Brixton, was likely to be the steepest climb of the journey and the highest point of the ride. It would all be downhill from there. I took back roads through Mayfair and then rode on the side of the road through Nasrec towards the N1 and headed for Eikenhof, then towards Grasmere. I crossed the N1 and made my way through the township at Grasmere. The township has rutted streets and uncollected, foul-smelling garbage dumped on the periphery. The general poor state of services contrasted with the care many residents were putting into their homes. Money was being invested in home improvement and beautifying with attractive gardens, an example of the new middle class at work. The residents are being failed, though, by officialdom, which is not able to match the progress in the public space that many are achieving privately. Postmasburg. Moving iron ore is big business. A dirt road, shown on one map as Sixth Avenue, snakes from Grasmere towards Fochville from where I was able to ride railway service roads. I headed for Potchefstroom, about 123km from my start, which I found to be surprisingly leafy and agreeable, especially in the students quarter. Wimpy is not usually my first-choice eatery, but its offering is pretty much spot-on for the needs of the long-distance cyclist, including the fact that the quick service gets you back on the road in no

- 4. time. I ordered the mega Wimpy, a mega cappuccino and a mega lime milkshake, and sat in the sun, flattening all in front of me. I hopped on a service road shortly after Potchefstroom and followed this to Klerksdorp. Because I was following the countrys main industrial artery, built to connect mining and its associated industry to the coast, I had expected a harsh landscape, but was still surprised by how degraded things were. The heyday of the mining here, gold, has long since passed, but the artery lives on in an often awful condition with unrehabilitated slime dumps, garbage, rubble and exotic trees, which flourish under such conditions. The landscape has been broken. The people who broke it have moved on to break other places. Some of the Kalahari roads were more than well maintained. I rode into Klerksdorp at dusk. An owl fluttered briefly two metres above me, taking me in. Klerksdorp was a bit of a surprise as I thought I was heading for Orkney, somewhat to the south. No matter. I would take a direct route using dirt roads to rejoin the railway line further along near Leeudoringstad. I rode through the industrial area of Klerksdorp, busy with traffic, and found a badly corrugated dirt road that was in such poor condition that it was almost car-free. After a while the condition of the road improved and I rode long, easy miles into the night. Although midwinter, it was relatively warm; I felt I could ride forever. Leeudoringstad is not much of a place when it is open, but arriving after 10pm, the little it has to offer was closed with the exception of a community clinic that stays open 24 hours a day. I stopped at the clinic to refill my water bottles, eat and consider my options. A friendly orderly was curious about me and my trip. Without me asking, he told me I was not allowed to sleep at the clinic as this was against the rules. I had given this some thought, but was dissuaded by a sign on the front door that said that it should be kept open as closed it would help facilitate the spread of TB in the clinic.

- 5. What the well-dressed road sign is wearing. Stealth camping I rode out of town looking for a place to sleep. This is sometimes called stealth camping, something I do not have too much experience of. The idea is not to be noticed so that you can have an uninterrupted sleep. One of my best stealth tips comes from the late Tony Traill, a Wits linguist of considerable pedigree. Traill, who compiled an English-!Xoo dictionary, spent weeks on end with the !Xoo Bushmen in Botswana. Once his group came across a cow, with no markings, recently killed on the main road. One of the men produced a knife and in one action cut off a haunch, jumping with it on to the back of Traills bakkie. He drove to a turn-off where the Bushmen used a branch to sweep their tracks so that these were no long visible to any potential pursuers. I have not resorted to using a branch to wipe my tracks, but I do carry my bike from the road to my camping spot to reduce the chances of being followed. I saw a locked gate that showed little sign of use. There was a clump of trees that would provide

- 6. shelter from the wind and, as I was to find out during the night, also from condensation. I climbed the gate and carried my bike to a suitable spot about 70 metres off the road. There were no lights of any farmhouses or any signs of other habitation. I rolled out my bivy and sleeping bag, blew up the three-quarter-length mattress and arranged my rain jacket as a pillow. I was too alert from the adrenalin coursing through me to fall asleep immediately, but after 20 minutes or so tiredness took over. So ended a 237km first day. I did not set an alarm but after a bit more than three hours sleep was awake and ready to ride again. Packing my bike took longer than it should have, it being about 45 minutes before I carried my bike to the gate, climbed over it and continued. I was riding alongside the railway line on a tar road, the two parting company at some point and me continuing to Makwassie, just over 20km along the road. Makwassie was asleep. I rode on the main road into Bloemhof. I am sure Bloemhof has other claims to fame, but the one I noticed is shortly before you enter which is the spot where twee singer Bles Bridges was killed in a car accident. His fans have erected crosses and other memorials at the spot. There is a good breakfast spot on the right as you enter the town. My plan of riding dirt and railway service roads was primarily for reasons of safety. If there was a tarred road, even a national road with a good shoulder, I was happy to ride it rather than the harder, bumpier, gnarlier dirt option. The N12 is such a road, leading from Bloemhof to Christiana and Warrenton. The road is on the north side of the Vaal River until it crosses at Warrenton. A hotel here offered steaks and a place to reorganise. With the steak I had two orange juices, a (much-too-sweet) strawberry milkshake and a couple of coffees. There was going to be a theme party that night, people were arriving in cowboy hats and boots as I left, heading to cross the Vaal again and go west. Using Google Maps on my phone I navigated out of town along an unusually broad road. This took me down to near the river where the road ended at well-barricaded houses. There was jiving music nearby. I could make out the shadows of people who, from their voices, I took to be young adults or teenagers. But as I got near them, they ran, hysterically. There is no real surprise in this, as with lights at handlebar and head height and two wheels and two legs, I could easily be mistaken for some kind of alien apparition.

- 7. On the northern bank of the Gariep (Orange) River. I retreated and tried a different tack. Just then a car drove along the road I was supposed to be on, about 100 metres in front of me. There was a long, seemingly endless uphill, which I chose to walk. At this point I had already been on the move for over 12 hours. Using different leg muscles and giving the others a breather made sense. The hill eventually came to an end and I rode on, in a happy space. Like the previous night I was cosy on the bike and the miles ticked easily by. It was Saturday night and when I came across the odd homestead there were party noises, but there were few cars out and no one abroad. My headlight caught long grass at the verge of the road and standing there was a lion! I braked and stared. The lion stared back. Heart racing, I braked harder and veered away from the animal. My light caught the tall grass again. The lion had changed to grass. The magic was over. It was getting to 11pm and I started looking for a sleeping spot. The trees on either side of the road were low and scraggly and the earth was uneven and broken. I checked out a few options over a few kilometres, before putting my bike over a barbed fence and climbing over. I found a spot about 30 metres from the road where the bush would offer some natural protection and unpacked my gear.

- 8. Day two finished with a combined 465km, about 30km short of Delportshoop, a town I had never heard of. I again did not set an alarm but planned to move off after about three hours sleep. I awoke in the early hours and looked at my watch. It was 3am. My body, exhausted, tired and sore, lay there resisting movement of any kind. Using willpower alone, I forced myself up, at the same time having an out-of-body experience during which I looked down on my reluctant body. It had a blue top and green shorts, colours I was not wearing, and was missing at least one arm and both legs, as though I had been the victim of a train running over me. I wondered later if I had dreamed this, but am pretty sure that I was awake as I had looked at my watch. In a contest between a mind determined to ride and a body not willing to do so, my mind won. It is hard, I found, in these early mornings, to get the amount of clothing right. I would dress for the cold but soon have to stop to shed layers as I was too warm. But then, just before sunrise, when the temperatures noticeably dipped, I would have to put the extra layers on again if I was not to freeze. I came to a T-junction. Delportshoop was to the left, the wrong direction, about 10km back. But I would need to go there to fill up my water bottles. The town was asleep when I arrived but I found a petrol station with water, refilled, and then somewhat begrudgingly retraced my route. About 20km from Delportshoop I found a turn-off to Ulco, a cement mine, which promised a supermarket just a few kilometres away. Indeed, not only was there a supermarket, it was open too. I bought two pies, yoghurt, orange juice, apples and chocolates, found a spot in the sun outside, and feasted.

- 9. The iron ore train is 3.7 km long. I had left the main industrial artery that joins the harbour of Cape Town to the heartland of the Witwatersrand, but nevertheless was on a sub-artery linking the mainline through to the iron ore belt at Postmasburg. The road was busy and unpleasant. I have a small mirror that fits on the end of the handlebars to help spot traffic approaching from behind. I make a point of getting off the road if there is two-way traffic, but the motorists, who were going in excess of 120km/h, were not enjoying me, or me them. After a while there was the prospect of joining the service road and I jumped at it. I rode, climbing slowly and making steady progress. A police car approached from behind. Incredulous that a cyclist was on this road, they stopped and got out for closer questioning. One, a gregarious fellow with some resemblance to EFF commander-in-chief Julius Malema, could not get his head around the fact I was undertaking such a journey on a bicycle, and asked several variations of questions about this. They told me what I could expect further up the road. The bad news was that in just five kilometres my service road would come to an end. I came to a somewhat disused railway station with an associated township that was very much in use and heaved my bike across the railway line. A kilometre further on was a petrol station that had a large supermarket diner attached. This, however, was shuttered. All that survived was a small spaza

- 10. shop where I bought an ice cream and drinks. This was Koopmansfontein. I headed out of town, climbing a bridge and seeing that beneath me was a railway line with service road. It led in the correct direction and looked like my best option rather than attempting to continue on the shoulderless road. The service road, though, was bumpy and hard work. I made painful progress, stopping a few times to sleep, bringing my number of catnaps that day to four. After 30 slow kilometres a dirt road offered an escape and I took it, re-joining the R31, which happily now had a rideable shoulder. I rode another 30km to Danielskuil, arriving at dusk, and deciding I needed a shower and TLC in the form of antiseptic cream for my backside. I checked into a B&B that could also feed me supper. Day three added 130km to my total. I left before breakfast and headed into the dark, but after just an hour of riding got a flat. The tyres are tubeless and are so designed to fix themselves with a sealant when they puncture. I could not find a hole or any damage to the tyre but it would not reinflate, even when I used one of the small bombs I carry for this purpose. I supposed that the bike shop had not put enough sealant into the tyre. I put the spare tube I carry into the tyre, a less than ideal option as this can invite further punctures, and carried on. Red earth I was now in the Kalahari (or Kgalagadi, to give the correct, original spelling), and rode easily to Postmasburg, a relatively large town with a dusty redness to it. Everything is iron ore here. There is even a takeaway joint called Iron Ore Chicken. I had lost my rear light and needed another spare tube and asked if there was a bike shop. I was directed to the Kraaines. A passer-by watched me put my bike at the door so I could see the bike from inside the shop. No, he said. Take it into the shop. They will steal it. I complied and was happy to find that the shop could sell me a tube. I could get a tail light at Shoprite at the shopping centre about two kilometres further on, the shopkeeper said. Along the way merchants had set up stalls, creating a vibrant marketplace. Two young men dressed in sackcloth were selling traditional medicines. They had a photograph of Haile Selassie. I have an interest in traditional knowledge and was keen to know where and how they had acquired their medicines. I also asked why they were dressed in sackcloth. Sacrifice, the one said. But I could also see that conversation would be difficult not least because they insisted on calling me My Lord. Further on, it occurred to me that all religions must have had small beginnings and that there would have been a time when Christianity and Islam, for example, had no more than two adherents. I found a Wimpy and ordered the usual. I would also need more water bottles and a new pair of socks, having lost a single sock, I know not where. I bought a bag of food at Shoprite, and luckily, also a bike light. I was drinking much more than I expected, possibly because of the dusty conditions and on the Sishen line I would have to ride perhaps as far as 200km without water.

- 11. Reorganising my bike took some time, it being just under two hours before I left Postmasburg. I stopped to take a photo of my bike against one of the mammoth trucks they use in iron ore mining, my bike being less than half the height of one of the wheels. I rode west to Beeshoek passing a mine with impressive headgear and what seemed to be a never-ending conveyor belt moving ore. A road sign rather improbably instructed no bicycles. Some roads were well maintained and graded smooth. One even had a water tanker on it, sprinkling water to keep the road damp to prevent damage. Others were dusty and unkempt, the large mining pantechnicons unleashing vast dust clouds as they sped by. The mining operations were soon behind me, though, and I settled down to enjoy the Kalahari, thanking the unknown people who had put these roads there so I could sail through on my bike. I was wondering, idly, who these people might be when I came across Carel, who was lying, in his construction uniform and cool shades, horizontal by the side of the road. I asked him what he was doing and was told that the road was under construction. He said he was from Port Elizabeth. I could not work out how he had managed to get a job that required him to do no more than lie by the side on the road. He said one of his responsibilities was to ensure that no one drove at more than 30km/h as this destroyed the road. I rode along Carels road for another 30km after seeing him but did not see a single construction worker but did see a few vehicles (which were going well in excess of 30km/h). A farmer was driving cattle from behind an open gate on to the road. I instantly stopped, not wanting to spook them and cause them to go in the wrong direction, but they did this anyway, the farmer having to drive on the side of the road to shepherd them back. We acknowledged one another with a wave and I rode on until I came to a T-junction. I knew now that the Sishen line was near. Then there was a rise ahead as the road climbed over a bridge to make way for the line below. From the top I had a view of the line with its supporting service road alongside stretching endlessly into the distance A set of signs warned that the road was private and closed to vehicular traffic. It was in great condition although I was to find that the Kalahari section, north of the Gariep River, can be sandy and where the road is in high use, such as where construction is happening, it can deteriorate badly. There were a few cars speeding along the road; most from what I could see were not Transnet vehicles. Great trains I also saw my first iron ore train. I was to find out later that these are 3.7km long. So long are they that the wagons carrying the ore are interspersed with locomotives that help to keep the whole thing moving. The train shatters the tranquillity of the open space, the noise of the wheels on the track being somewhere between an inscrutable screech and a symphony of steel. Then all was quiet again.

- 12. But I was to find that the electrical line that charges the elongated monsters has a life of its own. It can be as silent as its surrounds, but can periodically spring to life with murmurings, tingles, cracklings and intonations. At times it can bristle with life. I even thought at times I could hear what sounded like suffocated human voices as if bad people, perhaps those vehicles using the road without a permit, had been confined to the purgatory of the electrical cables on the Sishen-Saldanha line as punishment. The Sishen-Saldanha line stretched into the distance. Youd think the life these cables took on occasion would be because a train was approaching, but not so. As often as they gurgled to life, having said their piece, theyd go silent again. After a while, I cant be sure how long, I came across a set of buildings and a gate. A sign said I should sign a visitors register, but the cheery fellow in charge waved me on. His only concern was that I was heading into the night. Dont worry, I said, pointing to my handlebars. I have lights. It being late afternoon, there was no more traffic for the day: I had the road to myself. I cycled into the night, the most noteworthy event being the emergence of first two, then a third, porcupine. With natural protection, they did not run away but hung around, checking me out. One was large, probably close to a metre high. He clanged along the fence. I got off my bike to make sure I was not provoking the animals and walked along with one of them, it bristling next to me and me keeping a close eye on it. I found a likely campsite under a tree with soft red Kalahari sand below and the universe above. This was about 65km along the line, literally in the middle of nowhere, about 765km from my start in Joburg. I pulled out my bedding and was asleep in no time. The next section was uncharacteristically busy. There is a processing facility of some sort and electrical substations were being constructed. Earth-moving vehicles were reshaping the landscape,

- 13. taxis were bringing workers in and consultants and engineers were racing to the worksites. I read later that a concentrated solar facility is being built at Groblershoop, so I reckon this is it. The road was in poor condition. I bumped along until an exit showed that most traffic left the service road at this point. Up ahead was the Gariep River. Johann Rissik warns in his blog that under no circumstances should you cross any of the rivers (the Gariep, Olifants and Berg) on the rail bridges as Transnet - correctly - takes an extremely poor view of this. The Gariep has the only real water on the 1 500 km trip. The cyclist at any rate would need to visit Groblershoop, about 20km away, for supplies. I detoured off the line and rode along the north bank of the Gariep, stopping to take a photo at the turn-off to Knyp (how did it get such a name?) and of the abundance of water in the Gariep. Groblershoop does not have too much going for it, but perhaps because of all the construction activity, the petrol station as you enter the town has taken what used to be a small hole-in-the-wall shop and turn it into a diner and supermarket. Here were hot food, drinks everything the long-distance cyclist could hope for. The diner was still being constructed, a workman making an unbearable noise with a high-speed drill. The other challenge was that the new shiny tables were of an inferior design, meaning they rocked backward and forward in an uncontrollable manner. Eating breakfast was a one-handed affair, the free hand being used to stabilise the table. I tried to order hard-boiled eggs for the road but was told as the facility was new they had no way yet to boil water. I could, though, order takeaway hamburgers, which I did, settling on two cheese and egg burgers.

- 14. How did Knyp get its name? The ride back to the line is mostly downhill, this time with the bank of the Gariep to the north. The line and I were only of relatively recent acquaintance but already I was missing it and was looking forward to being back on it. I turned off the R32 on to a dirt road that would reunite me with the iron road, it coming in from my right. Infinity riding Crossing the Gariep had meant I had left the relatively sandy Kalahari behind in favour of the harder-under-foot Karoo. The road was in good condition and there was a tailwind; this was one of my best sections as I sailed along. With or without the tailwind, I think of this as infinity riding. You may have done long hours in the saddle, but there is a sense that so long as you can keep yourself fed and hydrated, you can continue forever. Couple the extraordinary endurance capabilities of human beings with the engineering of the bicycle and something transcendental happens: sustained, low-speed flight. The only time I felt tired was the exhausted feeling on the second night when I had the out-of-body experience. I felt sleep-tired at times, but never physically tired, although I will admit to a certain weariness as my ride neared its end.

- 15. I floated the 120km to Kenhardt, arriving at just before 7pm. Kenhardt is a desert town. Its water is pumped in from the Gariep over 100km to the north. It is in one of the harshest, driest and least-inhabited parts of South Africa. The area now is given to vast sheep farms, but until relatively recently, 150 years or so ago, it was the domain of men who hunted springbok and told tales of human sorcerers with magical powers who could take the form of lions and make rain. I visited twice in 2014 on the trail of //Kabbo, a Bushman who became the prime interlocutor for linguists Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd who in the 1870s took //Kabbo and other of his fellow Bushmen prisoners into their home in Cape Town, devising a way to write their language, ?/Xam, and spending 10 years documenting their world. //Kabbo came from the Bitterpits, about 40km southeast of Kenhardt. He collected and told his stories here, about the mantis and the moon, about the early race before people were people, and many besides. Bleek made a map of the area based on information supplied by //Kabbo. I rode some of the routes shown on the map. One ride took me through the wilderness where //Kabbo and his people somehow managed to survive. Christian culture has the story of Jesus spending 40 days and 40 nights in a wilderness; I was struck that /Kabbo spent his entire life in the wild. The miles ticked easily by on well-maintained roads. When we visited Kenhardt in 2014 the hotel had just two guests and was all but shut. Now the result apparently of another large solar project nearby both the bar and restaurant were full as were the rooms. I ordered supper and was told I would have to join a queue of 13 orders before me, but then the enterprising manageress worked out she had one precooked meal I could have immediately. Kenhardt was something of the edge of an abyss for me. The next place to provision was Loeriesfontein, 260km away. Johann reported that water was available at every second loop of the

- 16. road, 100km apart. Cellphone coverage is also sparse, particularly by Vodacom; hence my spare phone using MTN. I filled up my four water bottles and a two-litre bag in my backpack. I ordered six hard-boiled eggs for the road and bought chips, nuts and biltong. I put on my night gear, put new batteries in my head torch and left at 8pm. I took the R27 south out of town and was surprised how much climbing I had to do. I climbed and climbed and climbed, seemingly for at least 25km. This was a surprise as the Karoo is supposed to be flat. Later, checking on Google Earth, I saw that the total ascent was 100 metres, so maybe the weight of the packed bike or the general tiredness in my legs had to do more with the apparent rather than actual altitude gain. I rode until midnight, adding 35km to my total, which came to 945km. Trees had meanwhile over the past few days become shorter, fewer and then nonexistent. The bushes got lower and lower, meaning there was little natural protection in the veld for a place to sleep. My choice of bedroom that night was less than ideal. It was more rocky than it should have been and, as an experiment, I tried to dress less warmly to see whether my sleeping and bivy bags could do the job. I also did not wear my buff headgear when I went to sleep. It was handy but should have been on my head. Without the buff I lost warmth through my head and woke several times from the cold and rocky base. I was also overdue for a shower, adding to my discomfort. Altogether it was an unpleasant night. I ate my rather unappetising cheese and egg burger and left before sunrise, just 15km from the Transnet station shown on the maps as Kolke. The official in charge was unsure of the name, saying the names change from time to time. He told me his name was Jantje. Dis n Hollandse naam, I said, him nodding agreement. It was also the Dutch name of //Kabbo, Jantje Toeren. I asked whether there were showers and could I use one. The answer, happily, was yes. There are farms that border the line, vast spreads, but I saw few farmhouses and met just one farmer. He, with a worker, was entering a gate. The farmer said he came originally from Keimos, somewhat north of where we were, and that he had 1000 sheep. I looked at his land that was just broken rocks. It looks to me that you farm rocks, I joked, he smiling in return. Have you had rain, I asked. Yes, he said, beaming, two weeks ago. I actually knew the answer to this question before I asked it. We had first stayed at the Bitterpits in July 2014. It had rained the previous April. On returning in December 2014, farmer Nak Riechart said there had been no rain since. He undertook to SMS me the next time it rained. In late June 2015, an SMS came through: Ons het gister 28mm ren gehad. Nak. [We had 28mm of rain yesterday]

- 17. I was showered, but the fitful night took its toll. I did not seem to be able to get comfortable on the saddle. I stopped for catnaps. I took short walks. A headwind bothered me at times. I had lots of food with me. Dry wors. Fruit. Dried fruit. Snacks. But somehow it was not the right stuff to do the joint job of keeping me warm and moving. My progress was slow. Halfweg In the afternoon I came across Halfweg, a large station where the trains actually stop. I had understood from Johann that I might be able to buy food here, I imagined from a small shop, but there was no stationmaster or officials to ask. I also needed water. Two or three Transnet workers had got off a train and I rode over to one of them, a tall man with a warm handshake. I asked whether it was possible to buy food and provisions. Kassie, one of the drivers of these long trains, took me under his wing. The drivers use Halfweg as their base of operations while on week-long shifts. There is a hostel set a kilometre or so off the track where they are fed and housed. Kassie arranged with a manager of the hostel for me to eat. I could also stay overnight in a chalet if I wished. Kassie ushered me into the dining hall. A few drivers were eating, presumably getting ready for their next shift. I had hardly sat down when a large plate of bobotie appeared at the hatch behind me along with two cold drinks. I ate while Kassie told me about his job. Six trains run daily, three full, three empty. It takes 22 hours from Sishen to Saldanha Bay. The full trains cannot go faster than 60km/h; the empty trains do 70km/h. The trains have a total mass of 40000 tonnes, are 3780 metres long, use eight locomotives, 342 wagons and are said to be the longest production trains in the world. How you stop such a long train, I do not know. Each train has just one driver and one assistant. The line is mostly single track but there are 19 passing places. More drivers are kept in reserve than actually required should a train get marooned and the driver needs to be replaced. Kassie, who lives in Upington, has been driving trains for 26 years. He was insistent that he could supply me with other provisions for my trip, such as tins of bully beef from his stash, but I was equally insistent that I had enough food with me to make it to Loeriesfontein. One of the drivers could not believe that I was headed for Loeriesfontein on a bike and repeated this a few times. You going to Loeriesfontein now on a bike? Hes actually going to Cape Town, Kassie told him, also more than once. But this did not register. Youre going to Loeriesfontein, now, on a bike?! Kassie is well above average height and the drivers were by and large of sufficient bulk to look as though a train would rise to their commands. One was a hulking fellow. But there was also this petite drivers assistant whose name I did not catch. I know that the trains work off levers and electricity, but somehow still cant form an impression of someone so small being able to command so much steel.

- 18. Leaving Potchefstroom. Joseph rides a work of art bike. About 30km due west from Halfweg is the farm Hoezar West. Dia!kwain, a young man who supplied a legion of stories to the Bleek-Lloyd project, took his Dutch name, David Hoezar, from here. Dia!kwain, who had been arrested for shooting a Boer but was convicted of manslaughter as it was deemed to being in self-defence, also served time at the Breakwater Prison in Cape Town before moving in with the Bleeks. When he returned home, according to oral tradition in the area unearthed by archaeologist Janette Deacon, he was murdered near Kenhardt by Boers avenging the earlier death. Dai!kwan told stories (lots of them) about lions, but other animals such as the eland, gemsbok, hartebeest, quagga, ostrich and ratel (honey badger) too. One that stands out is the Broken String, a poem told with musical intonation of a ringing sound. It speaks of Nuing-kuiten, a friend of his father. Nuing-kuiten was a lion sorcerer who walked on feet of hair. People would see his spoor and say the sorcerer has visited us. The sorcerer travelled at night so that he could not be seen and shot at and so he did not maul anyone. He lived among the people hunting in a lions form until an ox fell prey to him. The Boers then rode out and shot him, he dying before he could teach his craft to Dai!kwains father. He died, and my father sang: Men broke the string for me and made my dwelling like this. Men broke the string for me and now

- 19. my dwelling is strange to me. My dwelling stands empty because the string has broken, and now my dwelling is a hardship for me. I still had 130km to do to Loeriesfontein. I had been struck while visiting the Bitterpits how little protection there was at //Kabbos living site, and had wondered how people had survived the harsh winter with just a hut put together from brush. Part of me wanted to sleep out on a winters night to get a sense of just how tough this would be, but a larger part of me opted for a warm, comfortable bed indoors. Now I would be experiencing a winters night in what the maps still call Boesmanland, albeit using high-tech equipment and with just about all my clothes on. I found a spot about 50 metres from the railway line defined by a few rocks perhaps 200m or 300mm high. There were also a few low bushes, but neither the rocks nor the bush as would offer any protection. I rolled out my bivy, bag and mattress, more or less organised the rest of my equipment, and with my bike to my one side, went to sleep. In terms of distance, the day was a bit of a write-off. I had only 115km to show for my efforts, bringing the total to 1060km. I was not ready for the fierce condensation. The area is so dusty and dry that it appears devoid of moisture, but enough dew fell overnight to completely saturate the bivy and the exposed bits of the sleeping bag. I was woken early in the morning by a car speeding along a road I did not know existed when I chose the campsite. I had actually chosen an island between the rail line and the road. It was too cold to get up. I checked my small thermometer, which showed zero degrees. My hamburger bought at Groblershoop was looking somewhat less than palatable and at the next station, shown on the map as Sous, I asked the woman in charge if she had a microwave. She did and heated the burger up for me, turning something gross into a passable meal. I sat on a bench at the front of her house in the sun and ate my hamburger. A few kilometres later I turned off the service road for Loeriesfontein, 60km off the line. I got there just after 3pm with 1160km done. Loeriesfontein is best known for its windmill museum, it having a complete collection of the 27 classic wind pumps that helped to tame the harsh waterless country. But Loeriesfontein itself is water stressed and has restrictions that limit the water supply to certain times of the day. It also claims the countrys first Spar where I bought six pies and other provisions. Pies, I had decided, were the long-distance cyclists food of choice, being easy to transport and with the added bonus of being easy to heat if the odd stray microwave could be located.

- 20. The hotel fed me my usual hamburger and chips with milkshake, coffee and orange juice, and also allowed me to take a shower in one of its rooms. Things were looking up. The desert road was 40km away. I was keen to get back to it. The road from Loeriesfontein drops and twists towards the coast. A makeshift-looking pipe runs alongside it, presumably bringing emergency water to the town. A large yellow road sign pointed to Loop 5. I had left the iron ore line at Loop 8 and would be rejoining it three loops later after a 100km detour. I turned off the tar road and headed towards Kliprand. I saw a farm, which looked tended, but still did not appear to have occupants. A highlight of this section was coming across two bat-eared foxes. They were trying to get away from me, but were confused by my lights, and I got a good look at them. After the wet previous night I decided to sleep in a culvert under the main train track. I reckoned that the train thundering above would be a small price to pay for a dry and relatively warm night. I found a culvert at about 10pm and arranged my bike to discourage any night animal from using the culvert to make its way under the track. A train came by as I was setting up camp, the noise somehow relatively dulled and not nearly as deafening as I thought it would be inside the culvert. My distance for the day was 180km. The culvert decision was a solid one and I had a good nights rest without any interruptions. In the morning I ate two of my pies before leaving. I rode with the Bokkeveld mountains on my left and the wonderfully named Knersvlakte on my right. There is not much to the Knersvlakte but an expanse of low bush stretching seemingly endlessly into the distance. The Knersvlakte is an expanse of flatlands with low brush. At the N7 the service road crossed the line and then veered away to join the tar road. I had to ride

- 21. along the tar to rejoin the service road. Large signs proclaimed what seemed to be as near as paradise I could imagine: the Knersvlakte Spens (pantry). Could such a place exist and just what kind of wonders could it deliver to the ever-hungry long-distance rider? Smaller signs told me that the Spens had such wonders as coffee. I could not see it but imagined, based on the urgency of the signs or was it my reading into the signs that it was close by. It had to be. I hardly wanted to ride say 20km in the hope of being able to get breakfast. Sure enough, just beyond a rise were buildings that spoke Knersvlakte Spens to me. I salivated, confident that I was heading for one of the great meals of my life. Happily I could see cars parked at the entrance. It was open. But cruelly - when I got there it was actually closed; the two parked cars were making their own refreshment arrangements. I climbed over a gate with two water bottles. A young woman was riding a bicycle in an odd way behind the Spens, weaving and looking as though she may fall off at any moment. She told me that they were away. The Spens would probably be worth redoing the whole ride just to breakfast there. I rejoined the line, riding a moonscape, with lots of ups and downs. The mines came to an end, leaving open Kalahari roads to cycle. The trains at first seemed to be unfriendly to me. With blackened windows it was impossible to see the drivers and most trains passed without a parp of recognition. They were icons of the industrial complex, the running dogs of international capitalism, supplying vast amounts of ore to be turned into steel to fashion all kinds of infrastructure and consumables for an insatiable, ill-fated globe. They were agents aiding and abetting the coming collapse wrung from endless development for its own sake. After Halfweg, though, the trains seemed friendlier and more drivers tooted me. I hoped that Kassie would lean his long frame out of his locomotive and give an enthusiastic wave, but alas, there was no

- 22. Kassie. My position on the trains softened: I now saw them as hostages, condemned to run endlessly up and down this track by their powerful unseen masters. I later downloaded Jack Londons The Road, his stories from the year (1894/5) he spent tramping trains and was struck by just dangerous this was, running alongside moving trains in the dark to board while the crew are doing their best to throw you off. One option for the hoboes was to climb aboard the springs beneath the carriages. Called on the rods, it required you stay awake. Sleep would mean youd roll over and be mangled on the track below, a not infrequent occurrence. On his very first push, as London calls them, a rider with the moniker French Kid, also a rookie, lay with both legs off. French Kid had slipped or stumbled that was all, and the wheels had done the rest. Such was my initiation into The Road. There was nothing similar in his jumping trains to me riding alongside the rail lines, except that he and his fellow hoboes were relentlessly on the move, sometimes not even staying in town long enough for a meal before jumping aboard the next train. I too was using the restless energy of the trains as I kept moving. Desert road The real challenge of my ride had been to get through the remote section between Kenhardt and the coastal belt where there was little food or water for almost 500km. As I began to leave the Karoo and near the coast, I knew that I was through, that I would make it. Wit Mossel Pot, Elandsbaai. I knew too that as I approached the Olifants River that I needed to get off the service road as it does not cross the river. But nonetheless I still rode on, because of my desire not to leave the desert road, until I could ride no further. The bridge was in front of me. I consulted Google Maps on my phone

- 23. and realised I had to backtrack more than a few kilometres, then use a tar road to Lutzville. This I did, setting up in the deli at the petrol garage where I ate pies yes drank lots of coffee and ate all kinds of assorted items. There was no easy way of rejoining my road. I headed on the tar towards Strandfontein on a section that had more than its fair share of long climbs. I knew the iron road was to my left but there was no opportunity to get on to it until the turn-off to Strandfontein. It was dark by now and I was conscious of a new sound: the dull roar of ocean waves breaking to my right. The Kalahari had drawn me in to the main act, the Karoo. Now the Atlantic reverberated happily in the dark to my one side as my ride drew to an end. I had for the last few days been thinking of my adventure. It seemed more of a song than a ride. The song of the desert road, with lyrics from the Kgalagadi and the Karoo, and to finish, an ovation from an ocean. The best thing about riding sections of tar, with cars flying by at 120km/h, is that it allows you to appreciate what the railroad offers, its own seductive rhythm. Yes, there are cars, but they are usually so few and far between that they hardly matter. I could have ridden the last night section forever. The night was cool. The lights of settlements on the coast were agreeable as was the lighthouse at Doringbaai, which for a time caught me in its circulating light. I saw two eyes reflecting my light in the distance. It appeared to be a small skunk or, more accurately, a ratel. Lamberts Bay had seemed a long way off when I reached Lutzville, but soon its lights came closer and closer. A kilometre or two from Lamberts I came across a security check with a closed boom and stopped to chat to the guard, who was intrigued that this guy had come out of the darkness on his road on a bicycle and that he had started his journey in Johannesburg. I got into Lamberts Bay at about 10pm and headed for Isabellas, a delightful eatery on the harbour. They were not about to accept new customers, which did not worry me as I was still full from the petrol garage meal at Lutzville, but helped me find a comfortable B&B where I would have a house to myself and the chance of another shower. Isabellas was still closed when I pitched up in the morning for breakfast but the hotel was a happy compromise even though the view was not directly of the small harbour and bird island. Being indoors, the soundtrack of the seagulls was missing. I had decided I would end my ride in Velddrif and headed along my road southwards, taking in Elandsbaai and a really good coffee shop about 20 or so kilometres down the road. The railway line headed for a tunnel but a coastal road allowed me to continue riding along what was an exceeding pleasant section, perhaps because the line was closest to the sea at this point. There were crayfish factories, which were closed, presumably because it was out of season.

- 24. Elandsbaai, where the rail line is closest to the coast. I cycled on through periodic rainfall, not serious rain, but enough to allow me to try out a new rain jacket, the one I had been using as a pillow, which I had bought before the trip. The jacket did its job admirably. The road came to an abrupt end at a tar road a few kilometres out of Velddrif. The road, actually, continued, but I could tell from the closed gate and little signs of use that this section of the road led to the Berg River. Velddrif was cold and foggy. I asked for a restaurant and was directed to Teyanas on the river, where I devoured a heaped plate of food and savoured the end of the ride. Graeme Murray, the inventor of the Murray Tour de Force, a stubby, wide saddle that provides good support for the seat bones, unlike the narrow competition saddles that give me back pain, lives in Velddrif and had invited me to stay. I had done 1500km over 8.5 days, riding about 18 hours each day, an average of 173km. The next day I rode on a tar road to Saldanha, where the iron ore line ends, caught a bus to Cape Town and then took a train home, riding the last few kilometres from the station back home. Kevin is the Mail & Guardian's business editor. http://mg.co.za/article/2015-08-04-song-of-the-desert-road