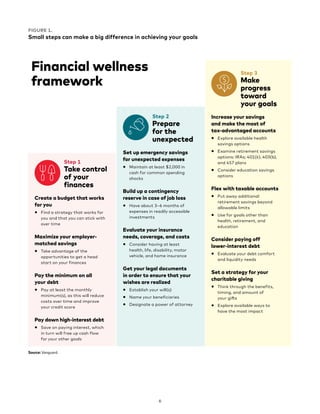

This document provides a three-step framework for financial wellness. Step 1 is to take control of finances by creating an effective budget, maximizing employer matched savings contributions, meeting minimum debt payments, and paying down high-interest debt. Step 2 is to prepare for the unexpected by setting aside emergency savings, obtaining adequate insurance, and creating important legal documents. Step 3 is to make progress toward goals by increasing savings in tax-advantaged accounts, paying off lower-interest debt, and considering charitable giving strategies. The framework aims to help households improve their financial situation through achievable next best actions.