Thesis_MSc

- 1. Wageningen University- Department of Social Sciences MSc. Thesis Rural Development Sociology The relation between social networks and the recovery process of households with differential vulnerability: A case study on the Peruvian earthquake 2007 July 2009 Kirsten de Vette MSc. Management of Agro-ecological 841106887010 knowledge and social change (MAK) Supervisors: Specialization: Dr. ir. G.M Verschoor Rural Development Sociology Dr. ir. G. van der Haar RDS-80430

- 2. Relation between social networks and recovery I Acknowledgements Before presenting my master thesis, I would first like to give special thanks to some people that made the fieldwork and thesis possible. First of all I would like to start with thanking the employees of the International Technology and Development Group (ITDG) in Peru, as for without them I would have probably not been able to do the numerous of interviews with the affected people. To start with Alcides Vilela, the director of the ITDG office in Chincha, for the enthusiastic response on my request for assistance in the fieldwork in the area and who openheartedly invited me to come and created the initial stable connection in the area. To Juan Bilbao, who made me feel comfortable from the very beginning and advising me about the do’s and don’ts in the area. To Jorge Mariscal who opened so many doors by introducing me to the wonderful people in the field. He was always there when I needed someone to talk to or discuss issues. To my dear female colleagues Nelida and Helga were so supportive and always took the time to listen to my stories. To Jorge Olivera for the many discussions that made me understand the situation of the recovery faster. To José, the driver, who was very attentive through coming to fetch me from UPIS-El Carmen many times. And of course to the other employees, who all very welcoming, very kind, open minded and supportive when it came to establishing the data was suitable for the research. Secondly, I want to express my sincere appreciation to the four households who opened up to me, trusted me and were so hospitable and inviting. In this research I used pseudonyms in order to protect the privacy of the households spoken to. Household Zuniga who integrated me in their life as being a part of their household and by doing this the most detailed descriptions of their relations with their social networks and the process of recovery came about. Household Manisco, who opened their house to me, who were so hospitable and invited me for lunch several times. They all took the patience to explain to me their process of recovery. The trust and confidence they had in me was truly appreciated. Household Luterio seemed at first seemed more distant, but after a while they truly trusted me. I was also truly touched by the invite to the commemoration.

- 3. Relation between social networks and recovery II The household Abada, who were able within their busy schedule to plan time for me and who were not only elaborative about their recovery process, but who explained to me the rules and regulations as much as they could. The four households made the experience a wonderful one that will always be remembered. Thirdly I want to thank both my parents for making it possible for me to study and who always supported me in my dreams. With special thanks to my mother and sister, who in this process of writing a thesis who allowed me to feel frustrated, but helped me tone down and get my feet back on the ground. Especially I want to express my gratitude to the editing that was done by Maaike. Fourthly, I want to give my special thanks to my boyfriend, Joost, who helped me through the struggles of the writing process. He took the time to listen, discuss and he assisted me with editing. Especially his patience with me and love for me is extraordinary. I want to express my gratitude to all my friends, for the many laughs and wonderful moments, as without them I would not have been able to finish the thesis. Maja thank you for going through this process with me. Writing the theses simultaneously made us share many coffees, library moments and moments of laughter. To the MAKS-22 group I must say that I feel blessed to have met all of you. The wonderful, but also challenging moments have taught me a lot over the last two years. Last, but certainly not least I want to give my sincere thanks to my supervisors Gerard Verschoor and Gemma van der Haar. Thank you for the support and for triggering me to unfold this process of writing. I appreciate the many hours that you have spent to provide me with the detailed feedback of which I learned so much. I truly feel that I have developed my skills and was able to finish the thesis, because of that. Kirsten de Vette Rotterdam, July 2009.

- 4. Relation between social networks and recovery III Table of contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................ I Table of contents ..................................................................................................................III List of figures and pictures ....................................................................................................V List of acronyms.................................................................................................................. VI Translations......................................................................................................................... VI Executive summary ............................................................................................................VII 1. Waves flowing underneath the ground of coastal Peru ....................................................1 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................1 1.2 The earthquake........................................................................................................2 1.3 The research location ..............................................................................................4 1.3.1 The population ................................................................................................4 1.3.2 Livelihood.......................................................................................................5 1.3.3 Broader economic influences...........................................................................6 1.4 Emergency response................................................................................................7 1.4.1 Emergency response........................................................................................7 1.4.2 Initial steps towards recovery focused on the private homes ..........................12 1.5 Problem statement.................................................................................................14 1.6 Thesis outline........................................................................................................15 2. Social networks in disaster recovery .............................................................................17 2.1 Disaster paradigms................................................................................................17 2.2 Previous research on the role of social networks in recovery .................................18 2.3 Towards an actor oriented perspective...................................................................20 2.3.1 Disaster recovery: an actor oriented perspective ............................................20 2.3.2 Social networks in disaster recovery: an actor oriented perspective................21 2.4 Conceptual model .................................................................................................22 2.4.1 The recovery process.....................................................................................22 2.4.2 Social networks in recovery...........................................................................23 2.4.3 Differential vulnerability ...............................................................................24 2.4.4 The complex view on recovery......................................................................24 2.6 Objective and Research questions .........................................................................25 2.7 Methodology.........................................................................................................26 2.7.1 Research strategy...........................................................................................26 2.7.2 Data collection techniques and sources..........................................................27 2.7.3 Data analysis .................................................................................................30 3. Household Zuniga: Building up social networks ...........................................................31 3.1 Introduction ..........................................................................................................31 3.2 Large household and few existing networks ..........................................................31 3.3 The earthquake: Loss of house, property and loss of livelihood .............................37 3.4 Weak existing social networks causes household to build new relations ................39 3.5 Vulnerability and building new relations to recover...............................................49 4. Household Manisco: Siblings and new relations............................................................51 4.1 Introduction ..........................................................................................................51 4.2 Household and existing relations in and outside of UPIS-El Carmen .....................51 4.3 The earthquake: Scared without a house and the loss of one income......................56 4.4 Support from siblings and new relation .................................................................57 4.5 The mobilization of capable relations through social activity and effort.................66

- 5. Relation between social networks and recovery IV 5. Household Abada: Social networks are willing and able to support...............................68 5.1 Introduction ..........................................................................................................68 5.2 Married couple without children............................................................................69 5.3 The earthquake: Limited impact............................................................................73 5.4 The successful mobilization of the social networks................................................74 5.5 Social position and access to capable social relations ............................................81 6. Household Luterio: New relations essential in the recovery...........................................83 6.1 Introduction ..........................................................................................................83 6.2 Household with social networks in El Carmen.......................................................83 6.3 The earthquake: Loss of both job and livelihood ...................................................86 6.4 Few “capable” social relations and mobilizing a new relation................................88 6.5 Social position, mutuality and establishing relations..............................................95 7. Conclusion....................................................................................................................97 References..........................................................................................................................102

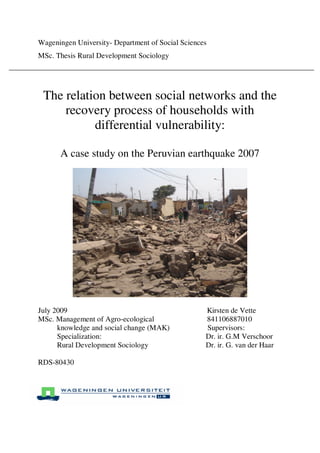

- 6. Relation between social networks and recovery V List of figures and pictures Figure1: Map of research location……………………………………………………………..4 Figure 2: Genealogy household Zuniga………………………………………………………..35 Figure 3: Genealogy household Manisco……………………………………………………....54 Figure 4: Genealogy household Abada………………………………………………………...71 Figure 5: Genealogy household Luterio………………………………………………………..85 Picture 1: Street in Chincha……………………………………………………………………..2 Picture 2: A destroyed houses in UPIS-El Carmen……………………………………………..3 Picture 3: Ruptured roads on the way to Chincha ……………………………………………...9 Picture 4: The emergency shelter of ITDG…………………………………………………….11 Picture 5: The borrowed property of household Zuniga……………………………………….42 Picture 6: The bathroom of household Zuniga………………………………………………....42 Picture 7: The new property of household Zuniga……………………………………………..48 Picture 8: The day care facility of household Manisco………………………………………...63 Picture 9: The kitchen of household Manisco………………………………………………….64 Picture 10: Lisa and Cidez Abada……………………………………………………………...69 Picture 11: Reconstructed house of household Abada…………………………………………80 Picture 12: The back part of the house of household Luterio………………………………….93 Picture 13: The new furniture of household Luterio…………………………………………...94

- 7. Relation between social networks and recovery VI List of acronyms FORSUR Fondo de Reconstruccion del Sur Fund for Reconstruction of the South INDECI Instituto Nacional de Defensa Civil National Civil Defence ITDG Solucionas Practicas International Technology Development Group CMPAD Comision Multi Sectorial de Prevencion y Atencion de Desastres Multi-Sectoral Disaster Prevention and Response Committee OCHA Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs PCM Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros President’s Council of Ministers SINADECI Sistema Nacional de Defensa Civil National Civil Defence System UNDAC United Nations Disaster Assessment and Coordination UPIS Urbanización Popular Interés Social Popular social housing development area Translations Albañil independent constructor bono por los damnificados government voucher Camioneta truck camote sweet potato chacra agricultural field certificado de posesión landholding certificate comerciante vendor Comunal community centre compadre the godparent (seen from the parents view) Lucuma Peruvian fruit maestros teachers (in this case for reconstruction) manzana Block negocio small shop/business pasar la voz word to mouth (telling someone) superiór college, studying after highschool título legal ownership’s title

- 8. Relation between social networks and recovery VII Executive summary This research aims to contribute to the debate on the role of social networks in the disaster recovery by adding knowledge. It describes the recovery process of four households with differential vulnerability. The case study takes an actor-oriented perspective by viewing the households as actors having agency that go into a complex process in which they interact, negotiate and struggle with multiple other actors in order to integrate the knowledge and resources through which disaster recovery unfolds. The research distinguishes itself not only by looking at the longer-term recovery, but also by providing a nuanced view of the mobilization of social networks in recovery. This nuanced description required the research to be of qualitative nature, for which I used informal interviews, genealogies, life histories, observations and some semi-structured interviews with organizations. The major findings of the case study indicated that the complex process of recovery is greatly influenced by the vulnerability of a household, which may be influenced by the employment status, the size of the household, the social position and the physical structure of the houses they lived in. This vulnerability affected to what extent a household suffered damage and thus also influenced the need for mobilizing social relations. Additionally, the position of a household, influenced by vulnerability, may determine the number of capable relations to turn to. The first case described here, represented the most vulnerable household. The pre-disaster vulnerability was identified by an insecure income, high expenses due to the size of the household (9), the weakness of the structure of their rental house and the fact that they were relatively new in the settlement. This vulnerability caused them, in face of the earthquake, to loose their house and rights to property. It also distorted their income generation. Besides this, their migration history and their lack of social activity had resulted in small and limited existing social networks that they could mobilize. As for the small networks, they supported during the emergency phase, but the relative vulnerability of these siblings resulted in immobilization in the recovery. Another relation mobilized resulted in a refusal of their request for help. Because of this, they had to mobilize dormant relations to get access to temporary property and become recommended to agroup to apply for a loan. The lack of access to certain resources, such as water and electricity, made them establish relations with the neighbours, who based on trust and compassion provided them with the resources. Another relation that turned out to be significant to their recovery process was their daughter’s connection with employees of the present NGO, ITDG. These employees felt the obligation and need to provide the household with furniture and some material to enhance their temporary living situation. In the pre-disaster situation, the second household had one stable income and another small wage that covered the expenses of this household (4). The physical structure of the house, especially, had made them vulnerable to the impact of the earthquake. The loss of the house, belongings and one of the incomes had created the necessity to mobilize their social networks. Their well maintained social activities and relatively long presence in the settlement, in comparison to the Zuniga household,

- 9. Relation between social networks and recovery VIII had created more social relations to turn to. However, most of these relations were also affected by the earthquake which had affected their ability to be mobilized. It was therefore that four siblings living outside the earthquake affected area were the most relevant relation to enhance their recovery. As siblings with the access to financial resources, they probably felt obligated to help them. Due to this household’s ability to mobilize more social relations, such as neighbours and friends, mutual cooperation and provision of small favours occurred more easily. Furthermore the household’s ties to an NGO had provided them with additional opportunities and connections. These were only possible, because of the skills of the mother of the household and the effort that she had put into assisting the NGO. The household (2) with lowest vulnerability of the four had miraculously suffered the least damage. Their low sized household allowed for a double income and fewer expenses. Furthermore, the fact that they belonged to a family with a relatively higher standard of living, which was also not affected by the earthquake, influenced their vulnerability positively. Their social activity and position within social relations created the ability to mobilize their existing social networks in order to access expertise, mobilize labour and access financial resources and materials. Through this it was unnecessary to mobilize or activate new relations to enhance their recovery process. The fourth household (4) had been vulnerable due to underemployment and this was worsened when the temporary job was distorted due to the earthquake. It clearly showed their necessity to mobilize relations with the ability to provide support, but the earthquake affected most of their existing social networks. Especially relatives were incapable due to vulnerability and therefore not mobilized. In fact, within their families, this household was thought to be doing the best out of all, causing first- degree relatives to request them for help. The fact that they had known their neighbours for eight years had led them to have some sort of mutual cooperation, but these friendships could not lead to improved access to resources and opportunities, which they needed. With this knowledge the establishment of a new relation with employees of an NGO could be explained. Build on the household’s cooking skills and construction skills, this relation based job opportunities. While it became clear that households differ with regard to the access that they have to resources, knowledge, expertise and skills, all households mobilized relations. It was clear that only capable relations were mobilized, which allowed some to mobilize their existing relations while others had to access dormant or new relations. When a household was considered to be doing relatively well, the possibility of being mobilized increased. It illustrates the mutuality of social relations. The ability to mobilize relations was dependent on factors such as migration, job, knowledge, social activity level and the vulnerability of social networks. The support that could be derived was not only depended on the capability of the provider, but also on whether it could be build upon the capacities, such as skills, experience, and resources of the household. To conclude, the knowledge generated provides a better understanding of the households’ agency which might be relevant to NGOs or other organizations. Further I recommend that mutuality and the relations with NGOs could be further examined.

- 10. Relation between social networks and recovery 1 1. Waves flowing underneath the ground of coastal Peru 1.1 Introduction “Like there were waves flowing below the ground taking down the house that took eight years to build.” 1 The earthquake of August 2007 unfolded in a true disaster for many Peruvian households on the southern coast of Peru. The affected households suffered severe damage to their houses and assets while some were additionally affected through a disrupted livelihood. In Urbanización Popular Interés Social (UPIS) El Carmen, the research location, ninety percent of the houses collapsed (ITDG, 2008). Taking into account that the personal experience above forms a typical illustration for a lot of households in the settlements, it indicates to some extent the difficulty to recover. Even though reconstruction programs were established by international organizations and the Peruvian government, households still had a long path to recovery. Upon my arrival, November 2008, households that had been excluded from reconstruction aid were still residing in emergency tents, without the prospect of external aid by national/international organizations or the church. Other households were living in emergency houses waiting for the government reconstruction aid to arrive. Even the households that had participated in reconstruction programs were still in the middle of the process of recovery. This illustrates that recovery is a long and complex process in which affected people can be greatly dependent on their capacities and the support of their social networks. This research delves into the nature of the recovery process of the households to describe the complex process in which the affected households interact with their environment and the actors within their surroundings. Frerks et al. (1999) argue that affected people naturally make use of familiar practices and social networks. They return to practices that they know and build on their capacities, while turning to members of their social networks. I therefore argue for the importance of investigating these social networks that may be mobilized. It is not expected that being a member of social networks necessarily means that relations are based on mutual cooperation or support. Neither is support or cooperation measurable in advance. This research therefore tries to provide a nuanced view on the relation of social networks and the recovery process of affected households. It acknowledges that different factors of vulnerability may affect this relation, through its effect on recovery only and the effect it may have on the social networks and or the ability to mobilize social relations. Through the description of how the social networks are 1 Translated from first informal conversations in UPIS-El Carmen.

- 11. Relation between social networks and recovery 2 mobilized and how they influence the recovery process I intend to generate knowledge to contribute to the debate on the relation between the social networks and the recovery process. This chapter presents the background of the research topic and describes the earthquake and its consequences on the research location UPIS-El Carmen. The research location, its population and its socio-economic situation provides an understanding of the difficulties that are faced by the affected households. After that, a description of the external response and its effect on the situation follows, which leads to the problem statement of this research. 1.2 The earthquake On the 15th of August 2007 at 18.41pm inhabitants of coastal Peru were taken by surprise by an earthquake with a magnitude 8 on Richter scale. The earthquake resulted from subduction between the Nazca and South American continental plate. The seismic shock created by this subduction lasted for three minutes. The epicentre was 145 kilometres south east of Lima, 45 km north-west of Chincha Alta and 110km of Ica, the capital of Ica department (NEIC, 2008). Although tsunami warnings were given to Peru, Chile, Ecuador and Colombia, these were false alarms. Picture 1: Street in Chincha

- 12. Relation between social networks and recovery 3 At least 519 people were killed (all but one in the Ica department), 1500 injured, about 45000 houses collapsed and 35000 houses were damaged (SINADECI, 2009). The earthquake’s reach extended well beyond the Ica department, but this department suffered the most. The Ica department is situated on the coast south of Lima and covers about 2132783 square kilometres (Regional Government Ica, 2009). The department is politically divided into five provinces which are composed of forty three districts. The province Chincha suffered most destruction in infrastructure and houses. Chincha is composed of eleven districts each with an own municipality that serves numerous villages and settlements. The research focused on UPIS-El Carmen which is a settlement of El Carmen, the centre village of the district El Carmen. These settlements were established on the basis of the social policy of the government to create housing area. It was the response to the increasing population in the end of the 20th century which had created a shortage in houses. The shortage became such a major issue that government action was required. The government initiated the establishment of the settlements similar to as they had done in other areas of the country. UPIS-El Carmen was established in 2000 on what used to be an agricultural field. This field was divided in manzanas (blocks) which was again divided into fifteen to twenty properties. The properties were distributed among the people that could prove they were in need of property and a selection was made based upon their necessity of an own property. All households in every manzana organized to start the construction of the houses. One constructor company was responsible for the settlement’s construction and the same materials were used for all houses. The government’s responsibility was to establish electricity and water connections in the settlement. Picture 2: A destroyed houses in UPIS-El Carmen

- 13. Relation between social networks and recovery 4 The earthquake resulted in an almost complete destruction of this settlement as ninety percent, a hundred and eighty out of the two hundred houses, became unsuitable for living through either severe damage or complete collapse (ITDG, 2008). The settlements construction appeared to have caused this huge percentage, as the foundation was only fifty centimetres into the ground, while massive walls of adobe material attracted more seismic shaking than a thinner wall would. Surprisingly no human lives were lost in this settlement during the earthquake, but people were forced to live on the streets without communication possibilities and without electricity. Water was scarce as most taps were covered with debris. The communication lines were repaired in four days and it took a week for electricity to be reconnected. 1.3 The research location Figure1: UPIS-El Carmen in the district El Carmen (wikipedia 2009) 1.3.1 The population UPIS-El Carmen houses a combination of people from different villages in the district El Carmen as well as migrants from other parts of the country. While the settlement is composed of mestizos and mixed ethnicities the majority of the population is Afro-Peruvian. The district is truly known for this Afro-Peruvian culture and its many traditional dances. The African slave trade during the 16th century had significantly increased the number of African descendants in the area. This resulted after Francisco Pizarro and his men had killed a significant number of Inca people during the conquest in 1533 (Wikipedia, 2009). It resulted in a shortage of labour domestically and in the farming

- 14. Relation between social networks and recovery 5 industry, which increased the demand for slavery. The African descendants became the most exploited and marginalized ethnic group in the country. Most of the residents in the settlement are Christian, which was brought by the Spanish, but the African descendants brought in special celebrations, dances and other traditional customs. These customs and traditions are very distinct from the rest of Peru. This is especially seen with the worshipping of the virgin El Carmen is a typical tradition that dates back from the colonial times and is greatly influenced by the African culture. It is taught to all residents when they are very young that the virgin of El Carmen is holy and it is truly believed that if you worship her good will come to you. With every celebration, festival or event an image of the virgin is present. Throughout the year, residents from 3 up to 30 years spent many hours practicing traditional dances to honour the Virgin El Carmen. At the end of the year on the 27th of December they perform the dances “negritos and las pallitas.” It is believed that this will bring the Virgin in the good spirit. This illustrates the big role that the religion plays in UPIS-El Carmen which was also seen at the moment of the earthquake. The residents, even though in complete shock of what had happened came to the parish to see if the Virgin El Carmen image and the church had not been affected. The church had been partly destroyed, but the virgin was spared. 1.3.2 Livelihood The livelihood of the population in the area depends on agriculture, fishing and manufacturing products. Cotton is the traditional product of the area, but extensive competition resulted in low prices and thus low profit. The middle and large farms, that were able to invest, have changed to non- traditional products such as grapes, avocados, asparagus, lucuma (typical Peruvian fruit), oranges, apples and camote (sweet potato). Most of these products are exported which explains the importance of the processing industry. The fishing industry in the province relies mostly on anchovy, sardine, tuna and sea bass. Also this industry mainly focuses on export, where canned fish and fish meals for poultry belong to the main export products of Peru (FAO on Peru, 2009). Roughly sixty percent2 of the men in UPIS-El Carmen work for the corporation Fruticola, locally known as Fruchincha. It is the largest factory in the area, that focuses mostly on export of asparagus, avocados, grapes and has a separate factory based on canned fish. The work is mostly temporary or seasonal, but some work full time. The different harvest times and different labour intensity per product determine the demand of labour in the factory, which causes the demand for employees to fluctuate. Underemployment is a consequence, which means that the people that work can not work full time. For the people working on the agricultural field the same situation applies and employees often work on temporary basis. 2 Mentioned by Cidez Abada and the ITDG

- 15. Relation between social networks and recovery 6 In the meanwhile the supply of labour exceeds the demand, creating advantages for employers in the fruit and vegetable industry, whether farm owners or factory directors. The wages of employees can be kept to a minimum. Even though the legally recognized minimum wage is 500 soles per month, normal wages on the field and in the factories are 12-20 soles (3-5euro) a day and even by working fulltime this minimum is not obtained. The external control on the provision of minimum wage seems to be absent and employees do not tend to complain in fear of their replacement. Another advantage that employers enjoy is the high criteria they have for jobs. As the work is physically hard, both on the field and in the factories, the preference of employers goes out to people under 25 years of age. Furthermore men are preferred over women. This results in an increase of unemployment in the age groups above 25, especially with regard to women. It can explain why many women in UPIS-El Carmen work in and around the house and a lot of households have tried to set up a small store. In UPIS-El Carmen there are about thirty small shops, selling mostly food and drinks, but some have extended their products to beauty products and or clothes. This business has become very competitive and most shops earn small profits only. The competitiveness of the shops has also created some pressure on the owners of these small shops, which was seen by the possibility to buy on credit. As the possibility to buy on credit is sometimes requested in times of hardship this can create difficulties for the owner. Denying the credit, however, may mean the loss of customers. The consequence of all these issues concerning employment and income is that a lot of the households in UPIS-El Carmen are unable to satisfy their basic needs, which can be defined as poverty (World Bank, 2009). Whereas specific statistics lack on Chincha, the Ica department has 41,7 % of the population living with an average income of less than one dollar a day (World Factbook, 2008). 1.3.3 Broader economic influences This area-specific economic situation is influenced by the history of the nation’s economy. Namely the Peruvian economy is, in 2009, still recovering from the collapse of the economy in President Garcia’s previous term. Garcia’s administration implemented the policy of “Economic Heterodoxy” which meant an expansion of public expenditure and limitation of external debt payments. This resulted in hyperinflation of 7650 % and therefore reduced the per capita consumption to levels of before 1960 (Parodi and Trece, 2000). While the nation had not been a wealthy one before, this situation increased poverty. When Alberto Fujimori was elected in 1990 he ended price controls, protectionism, restrictions on foreign direct investment and most state ownership of companies. The foreign investment in the nation caused economic growth and a drop in inflation. But the cold spell of El Niño weather phenomenon created a stagnation in the economy’s growth from 1998 to 2001, due to crop failure. The effects remained to be seen during president Toledo’s term (2001-2006). Toledo’s party implemented a program to attract investment and restart privatization, but the economy did not

- 16. Relation between social networks and recovery 7 yet react as Toledo had anticipated. When Garcia took office in 2006 he put in to work an effort to create macro economic stability by a fiscal program that targets the deficits. The economy started to grow and reached a growth of 9 % during 2007 (World Factbook, 2009). However, the rising oil and commodity prices caused an inflation of 5,5 % at the beginning of 2007 (World Factbook, 2008). Also efforts to boost construction and create jobs, by investing three million dollar in an employment stimulus package and drawing investors, have not yet had result on the underemployment. The effect that this macro-economic effort is supposed to have is not achieved in the province of Chincha. While the inflation is illustrated by the increasing and unstable prices of consumer goods, the wages have not yet increased. The economic prosperity of the country is not felt by the poor in society since the major issues of un- and underemployment combined with the minimal wages remain unaltered. 1.4 Emergency response The previous part has shown the effects of the earthquake and introduced the research location with its socio-economic circumstances. The remaining of this chapter starts with providing a review the emergency response and its relation to the way society reacted in the situation of the earthquake. It provides an overview of the new actors that arrived in the area after the earthquake. This is followed by discussing the external aid for reconstruction which may have affected the way that people mobilize their social networks. 1.4.1 Emergency response In UPIS-El Carmen the above described vulnerability, in the form of underemployment and the fragile construction of the houses, made the earthquake turn into a disaster where the affected people were in need of emergency relief. The affected people came together, on the plaza and the agricultural fields. All traumatized by what had just happened, the people spoke of what happened and what they had lost. Most tried to find relatives, friends and the people with whom they closely related and were occupied with seeking ways in which they could provide themselves with food, water and a shelter. It illustrates clear collaboration within the social networks. In the first few days relatives from outside the affected area came by to check upon their family members sometimes bringing some basic necessities in the form of food and clothes. As it took the external aid a week to arrive in UPIS-El Carmen, these basic necessities provided by relatives were crucial to the survival, making the social networks in the emergency phase essential. When the earthquake struck the Peruvian government had a disaster response plan in place, because the country is prone to different kinds of natural disasters, such as floods, earthquakes and landslides. This National Civil Defence System (SINADECI) seeks to manage issues related to

- 17. Relation between social networks and recovery 8 disasters, but the structure of this system is complex and very hierarchical. It is led by the President’s Council of Ministers (PCM) under which the Multi-Sectoral Disaster Prevention and Response Commission (CMPAD) functions. The CMPAD coordinates evaluates, prioritises and supervises assistance and support (Savage and Harvey, 2007). These tasks are carried out by the National Civil Defence (INDECI) who creates the rules, policies and strategies. Subsequently the INDECI provides the immediate assistance by channelling and organising national and international emergency relief (Savage and Harvey, 2007). This is done through the Civil defence Committee which is supposed to be established by the mayor of each municipality. The committee should include governors, police, armed forces, churches, companies and NGOs. The procedure is that the response starts through this committee. Whenever the disaster exceeds the capacity of the district to handle it, the responsibility is given to a level higher in hierarchy, which means it goes from district to provincial to regional to national. After this earthquake the INDECI started off with the rescue phase after which they led the emergency relief. The international aid was supposed to go through their system, but inefficiency of the system led to problems. The responsibility of responding lay at the Civil Defence Committees, which were assumed to be in place. Many districts, such as the El Carmen district, had not yet established a Civil Defence Committee. A second issue was that the shortage made it impossible to create one now. This was mainly because the personnel that worked in the municipality had also been busy with the damage and losses suffered in their families. The enormous chaos, the shortage in personnel and the late arrival of aid proves that the emergency clearly exceeded the capacity locally. The tasks had to be taken over by the Provincial Civil Defence who was in no better position to handle this kind of disaster (Savage and Harvey, 2007). Via the Regional Civil Defence the responsibility was shifted to the INDECI itself. This process took time as none of these levels acknowledged their incapacity to respond and this hierarchical structure further delayed the actual response. Besides that, President Garcia had instead of building on the existing system, created a parallel system called Fund for Reconstruction of the South (FORSUR). This was a structure of all regional and provincial presidents and mayors of the districts. The tasks had remained unclear and through the duplication of these systems certain tasks were not carried out by anybody, because the responsibility of tasks was unclear. These two systems created chaos and a lack of coordination which greatly hindered emergency relief after this earthquake. The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) came in to improve the organization together with the United Nations Disaster Assessment and Coordination (UNDAC). The UNDAC was employed to carry out rapid assessment and support the local officials in the INDECI in coordinating international relief efforts. Not only did OCHA improve the coordination of multiple incoming organizations, but especially they tried to coordinate the flows of aid. These international efforts were mostly concentrated in Pisco, the town that had suffered the most losses of lives. With the

- 18. Relation between social networks and recovery 9 OCHA and UNDAC located in Pisco, the response there had been relatively well organized. Also the accessibility via port and airport in Pisco had enabled the aid to arrive. The areas beyond, however, were not very well reached as the roads and bridges towards the areas had been damaged during the earthquake. The response for the province Chincha had thus been slow. The government sent numerous of teams to repair parts of roads and bridges so as to improve the accessibility to the areas and allow for response. Picture 3: Ruptured roads on the way to Chincha five days after the earthquake (source: ITDG 2007) The first local NGO, International Technology Development Group (ITDG), arrived after five days in UPIS-El Carmen, but some more distant villages had waited up to thirteen days for the first aid to arrive. The INDECI had at the same time arrived, providing some tents for people to sleep in on the plaza of UPIS-El Carmen, while other people had created small tents with blankets and wooden sticks. In the meanwhile, the local factory Fruchincha, where numerous men work, started emergency relief by providing El Carmen and UPIS-El Carmen with food aid, during breakfast and lunch. Prepared food was distributed on the plaza of El Carmen and plaza of UPIS-El Carmen to all families and every household was able to benefit from the aid that lasted for two and a half months in total.

- 19. Relation between social networks and recovery 10 Further aid distribution in El Carmen and its settlement had been chaotic. Individuals, private companies, and some NGOs simultaneously tried to provide help, but the problem in general was duplication of efforts as different parties assessed different needs. The lack of cooperation between them led to uncoordinated action. The local priest mentioned that he had tried to convince the people to divide themselves into groups in order to easily and equally distribute among groups. The main square of El Carmen, however, became the drop off point and people were afraid of missing out which resulted in abolishment of this idea of groups. The emergency relief, simultaneously, became unequally distributed, with the ones living near the plaza receiving the aid always and often a lot of it while for the people living further away, less was left. As the settlement of this centre village, UPIS-El Carmen, was five minutes walking from this drop-off point, the households in the settlement received less aid. Another effort that the priest wanted to introduce, to eliminate the unequal distribution, was to separate tasks between the municipality and the parish. The priest would then take the responsibility for distributing the incoming food aid, water and medicines, while the municipality would take care of distributing the clothes and other materials. It appeared that the municipality did not have the capacity to take on board such a task. The aid brought in by the church arrived in the end of August 2007 and it was the task of the priest to equally distribute the incoming aid amongst all villages in the El Carmen district, since it is the only church in the district. This was managed from the parish in El Carmen the centre of El Carmen district, where all incoming aid was stored and the church started to function as an external aid distributor. The people of El Carmen became agonized by the fact that they saw numerous of station wagons and trucks coming with aid while, in their eyes, relatively little aid was distributed in their village. The faith in the priest dropped among a lot of the people in the centre village and UPIS-El Carmen, while comparing to most villages in the district they were best supplied with other external aid. The citizens accused the priest of corruption, because he was supplying the more distant and less fortunate villages in the district3 . The priest, Lorenzo Bergantin, became very disappointed, as El Carmen and UPIS-El Carmen were receiving relatively a lot of other external aid. The priest recalled mentioning to the citizens of El Carmen and UPIS-El Carmen “With your hands full you still ask for more. But I am trying to distribute aid to all villages, even the ones that need it more than you do.” In the meanwhile each household in El Carmen and UPIS-El Carmen had received three bags with basic necessities, each roughly a month apart from one another. After three weeks the INDECI had created funds to coordinate a clean up of solid waste and debris in UPIS-El Carmen by the citizens themselves. Through the municipality, the INDECI had created an incentive of 90 soles (22,5 euro) per week for all residents that helped with the clean up. This clean up started after the first week of September and lasted until the end of September 2007. 3 Padre Lorenzo

- 20. Relation between social networks and recovery 11 Simultaneously some of the citizens of UPIS-El Carmen organized themselves in groups to try and remove the debris from their properties. The emergency shelters provided by ITDG could afterwards be built by the affected people themselves on part of the property or next to the property. Within two months after the earthquake all residents of the hundred and eighty houses that had been destroyed were supplied with an emergency shelter. The emergency shelter had been financed via an aid organization in Spain and consisted of wooden poles with thick cotton fabric wrapped around it, also covering the roof. Sometimes plastic was used to make the roof waterproof. Picture 4: The emergency shelter of ITDG During this emergency relief the government had been accused of corruption. Especially through the system of the INDECI, aid, such as food clothes blankets and medicine, disappeared. It was found that people in power positions took aid home, distributed it amongst their family and used it for other purposes. This was proven due to numerous of confiscations in homes of mayors, INDECI coordinators and other government officials. To summarize the many different ways to respond by the actors involved, such as multiple NGOs, the municipality, the companies and the church, created difficulties in the actual distribution of aid. Chaotic, uncoordinated action and most of all unequal distribution was the result.

- 21. Relation between social networks and recovery 12 1.4.2 Initial steps towards recovery focused on the private homes The affected households living in the emergency shelters had to initiate the recovery. The recovery phase is distinguished from the emergency phase in that it is on the longer term, not with mere survival in mind, but it concerns the reconstruction, repairing and replacing belongings and rebuilding the livelihood. To initiate reconstruction it was necessary to have título (legal ownership’s title) of property so as to avoid legal issues. Besides having a place to start reconstruction, an owner’s approval is a necessity to legally be entitled to the property and the house on it. Not all households living in UPIS-El Carmen had título when the earthquake struck. Namely, with the establishment of the settlement in 2000, most households received the certificado de posesión (landholding certificate), but not everyone applied for título afterwards. The certificado de posesión includes the map of the area that you possess, the surface, the division of the property and the identification papers of the people living on the land. The certificado de posesión is registered in the municipality (in this case in El Carmen). Once the citizens have the certificado de posesión, they can start the application for título. The start of this process is to register the property in the Chincha municipality with the certificado de posesión. It is then necessary that the municipality controls your certificado de posesión and will check whether the applicant actually lives there with the number of persons he/she applied with. It can take up to several months before the municipality has checked these criteria. Subsequently the applicant has to return to the municipality in Chincha where the next requirements are discussed. This means the owner needs to pay taxes according to praised value of the house and the number of people living there. This, however, should be paid in El Carmen municipality. Also the duties of living in the municipality are to be paid. When these payments are fulfilled, the applicant returns to the Chincha municipality and the registration of ownership is made, but not yet officially valid. This registration is send to the official register in Ica, the capital of the department. This entire registration process can last up to several years and takes up working time of the applicant. Due to the described bureaucracy and costs several households in UPIS-El Carmen did not apply for título after having received the certificado de posesión. Other households had come to live in UPIS-El Carmen well after the establishment and had neither certificado de posesión nor título. The government wanted to help out and provided the households with certificado de posesión, with the opportunity to receive título for free. It meant that only with the correct and official registration of the certificado de posesión, this título could be received. This created exclusion of households that moved to UPIS-El Carmen later than the establishment of the settlement and to households that rented property. The following step made by the government was the provision of a bono por los damnificados (government voucher) that was worth 6000 soles (1500 euro). With this voucher people could buy material for the reconstruction of their house. The card functioned like a credit card with which the

- 22. Relation between social networks and recovery 13 people could obtain 5400 soles (1350 euro) worth of material and they could get 600 soles (150 euro) in cash from a bank. The criteria for this government voucher were título and proof of living there during the earthquake. Interestingly enough no such programs existed for the people who did live in the affected area but did not have the certificado de posesión. The households who already had título and the ones that had received the free título, were able to officially apply for the government voucher. The process of application was delayed due to inefficient work of the INDECI who had made the District Office responsible. This District office was supposed to control the houses for damage and find proof that the applicant lived there during the earthquake. Residents in UPIS-El Carmen accused the municipality of corruption as they felt like the friends and relatives of the employees, of the municipality were given precedence during this control. It illustrates how connections might increase the ability to advance faster than those without the connections. However, even if this was the case, there is no implication that this precedence resulted in earlier receipt of the government voucher. The Civil Defence District Office distributed the first government vouchers in February 2008, and it was claimed by the municipality that the distribution went from manzana (block) to the next. This said, in the end of January 2009, eighty percent of the approved applicants had not yet received the government voucher (ITDG, 2008). The interesting issue is that while the president mentioned that 180 million soles had been spent on the vouchers, it seemed as if this money evaporated. While some were waiting for the government vouchers, ITDG came back in January 2008 and mentioned that they were trying to receive funds for a reconstruction program in UPIS-El Carmen, but the official announcement had not yet been made. In February 2008 a ‘Japanese NGO’ announced a reconstruction program for 100m2 houses. As this NGO was the first to announce a reconstruction program and the size was appealing, eighty households in UPIS-El Carmen enthusiastically applied. The only requirements according to this Japanese NGO were a payment of 80 soles (20 euro) and the ownership papers had to be handed over for copying. This Japanese NGO left with the money and papers to arrange the start of reconstruction, but did not return. When the ITDG returned in the March 2008 to officially announce its reconstruction program for two room houses of 32m2, most households that had applied for the Japanese reconstruction did not apply for the ITDG reconstruction. During the investigation it was mentioned that 32m2 had been less appealing compared to the 100m2 offered by the Japanese NGO. Whereas normally ITDG had to do a survey to select the households, here all households that applied were selected. The only criterion was the título to avoid legal problems. An NGO can namely not start reconstruction on property that is owned by someone else. Sixty-four out of the hundred- eighty households in UPIS-El Carmen had started the ITDG reconstruction already when the other households discovered that this Japanese NGO had unfolded a major scam. By that time the ITDG had already redirected its funds to other villages and could not help the households that were deceived by the Japanese.

- 23. Relation between social networks and recovery 14 The ITDG reconstruction started where the ITDG provided material and employees of the ITDG, maestros (teachers), taught the participants how to reconstruct. The affected households organized with other beneficiaries, which were often households living in the same manzana, to reconstruct. It was an obligation to come to the meetings to be included in the decision making and discuss problems that were faced. Some of the meetings included lectures on disaster preparation and mitigation. As the priest had seen the exclusion of many households due to lack of ownership and due to the scam he provided an offer for reconstruction to those who had been excluded. He was unable to help the households that rented a house, as the household had to have bought property. The owners of these houses did not dare to come to ask for the reconstruction aid as it was known to the priest that these people did not live there during the earthquake. The church offered reconstruction with a version of adobe material. As this was the material that had collectively failed to resist the earthquake, people in UPIS-El Carmen did not want this reconstruction aid. The adobe offered by the priest had been especially created to be more resistant to seismic shocks, but this was not good enough for the people in UPIS-El Carmen who were too scared. Only three households accepted the church aid according to the priest. The rest rather lived in an emergency shelter. The priest mentioned this could have been related to the fact that the faith in the priest had dropped in the village of El Carmen and UPIS-El Carmen and said: “So I decided to help the people in another area who gratefully wanted the reconstruction.” The priest had chosen this material especially because a lot more houses could be build with the funds he had received. To summarize, the reconstruction efforts of the affected households were severely limited due to the difficulties of property and ownership. Besides that, while the government voucher had been a great idea, some households did not receive it and were unable to start reconstruction. Others were completely excluded from all sorts of reconstruction aid. The households that did participate in the reconstruction program of ITDG, at least had a part of their house reconstructed, but were still dependent on themselves and their own capacities to mobilize resources when it came to full reconstruction of the house. The social networks are thought to possibly influence this by providing access to resources in terms of finances, knowledge, material and connections. 1.5 Problem statement To describe the problem statement a small summary of the above is necessary. The households in UPIS-El Carmen were severely affected by the earthquake, where ninety percent of the houses were partly or completely destroyed. Some households faced more damage to their belongings than others and for some the earthquake resulted in a disruption of the livelihood as a whole.

- 24. Relation between social networks and recovery 15 The unequal distribution of aid was a great problem during the emergency phase, but with reconstruction aid some households became completely excluded. This aid depended on the assets, property and its título that some households did not have. The result was that some households had lower capacities to respond. Even the households that had received the reconstruction aid still had a long and complex process towards recovery in which they had to build upon their own capacities and those of the ones within their social networks. Where previous research has seen the role of social networks in recovery as positive, a nuanced view of the influence of social networks on longer term recovery is lacking. The problem is that there seems to lack a detailed and nuanced description about the role of social networks in the longer term recovery process of households. Therefore this research tries to distinguish itself from other research by looking at the longer term. It focuses more on investigating the role of the social networks in the recovery phase. It thus intends to contribute by filling the gap in knowledge that seems to exist. This is done by providing a detailed description on how “the survival, protection and relief of affected people rests in the hands of the affected people” (Hilhorst, 2007:19). It is then interesting to investigate the recovery process of the affected households, while analyzing the social relations that are mobilized and activated in the after math of a disaster. In this process it is necessary to account for the differences between households, with regard to their vulnerability. 1.6 Thesis outline To start this research and fill the gap of knowledge about the recovery process of affected households with differential vulnerability and its relation to their social networks the following chapter will first present the main disaster paradigm through which I perform the investigation, which is followed by previous research on disaster recovery and the influence of social networks. Subsequently the perspective used to view the concepts introduced, after which the view taken is described. This theoretical part leads to the questions that this research wants to address and then discusses the methodology used to answer these questions. In this part the qualitative nature of the research is described. The triangulation of data collection techniques and sources are explained as well as the way of analyzing the data collected to enable drawing conclusions from it. Chapter three starts with describing the household Zuniga and its recovery process. This household was the most vulnerable household of the four investigated, who due to migration had experienced a disruption in most of their social relations. The relatives of the mother’s side were crucial during the survival, but incapable to provide support during the recovery process, which is why household Zuniga did not mobilize the relation. The case argues in favour of the importance of social networks as this household tried to mobilize dormant networks and establish new relations that were expected to have the ability to support.

- 25. Relation between social networks and recovery 16 Chapter four introduces the second household, Manisco, in which the significance of financial assistance of the siblings came to the surface. These siblings did not live in within the borders of the affected area and had the capacity to provide support. The support enhanced the recovery by the access that it gave household Manisco to financial resources to increase their saving. The recovery process of this household argues also for the significance of creating a new relation, as the established relation with an NGO resulted in the recovery of the disrupted job through the provision of material and through the provision of a new job opportunity later on in the process Chapter five elaborates on the third household, Abada, whose recovery process was significantly enhanced through the support of the social relations who lived nearby and were not affected by the earthquake. The willingness to provide support resulted in financial assistance as well as manual labour or the provision of materials for reconstruction. Chapter six discusses the fourth case, the Luterio household, which shows that having relatives in the earthquake affected area lowers the ability and willingness to mobilize them. It does provide an argument for the mutuality of relations by explaining that the affected household itself was mobilized via first degree relatives. Furthermore it describes that establishing relations with an NGO can be essential for the recovery of the household. The last chapter will bring all the findings together and also focuses on the differential vulnerability of the households. It tries to link vulnerability to the need to mobilize the social networks, but also links vulnerability to the ability to mobilize certain relations during the recovery process. After describing the drawn conclusions, the practical implications and recommendations for further research are mentioned.

- 26. Relation between social networks and recovery 17 2. Social networks in disaster recovery The previous chapter has introduced the disaster, the external response, the research location and the problem statement. This chapter explains in detail the theoretical framework chosen. First it discusses the main paradigms used in disaster research and explores previous research done about social networks and their mobilization in disaster situations. Then the chapter introduces an approach that puts the actor central and acknowledges the dynamics of recovery as a process of interaction, negotiation and social struggle. The assumptions that this approach takes to view the relevant concepts are explained, which assisted me to form the theoretical framework chosen. It presents the angle with which this investigation tries to enter the debate on social networks’ mobilization in disaster situations. Subsequently the research questions are presented that allow me to generate knowledge that contributes to the theoretical debate. Then I describe the methodology with which I answer these questions. 2.1 Disaster paradigms In order to investigate disaster response locally there is a need to discover how this earthquake turned into a disaster and thus how to view disasters, vulnerability and response. Disaster research until the eighties tended to equate hazard to disaster. This was followed by the “structural paradigm” that marked the eighties. The latter presumed that reviewing a society at large could provide an explanation as to how a hazard turns into a disaster. This paradigm argued that the root causes of vulnerability, such as poverty and other social issues, created the possibility for a hazard to turn into a disaster. It assumed that addressing these root causes would lower the disaster risk (Frerks et al., 1999). For many years this was the focus of disaster research, until research was done about the mutuality of human activity and the environment. Evidence was provided that human activity could create environmental degradation and with this degradation natural hazards started to be on the increase. It partly stemmed from the complexity theory which according to Waldrop (1992:11) was the theory that mentioned that “change in systems are complex in the sense that they consist of many independent agents that interact with each other in many ways.” The mutuality of the environment and society surfaces and this mutual constitution argues that through the interaction also disaster vulnerability and response occurs. Where complexity theory is based on systems thinking, it “denies agency and diversity and puts unwarranted boundaries around people and phenomena” (Hilhorst, 2004:1). Instead she argued to use the term social domains where people are interacting, negotiating and struggling within several ‘systems’ simultaneously. Domains are then the locations where the knowledge of multiple actors is

- 27. Relation between social networks and recovery 18 integrated, shared and thus the place where the interaction negotiation and social struggles take place. 2.2 Previous research on the role of social networks in recovery When doing research on the role of the social networks in recovery it is important to review the already established knowledge with regard to this debate. Overall, previous research assumed that social networks play a positive role in disaster situations. This assumption is seen in the concepts used to describe the functioning of social networks, such as social capital and social security. Social capital views social networks as an asset that increases the ability to access resources, information and thus functions as a readily available path to walk on in times of crisis. Lin (2002) described that actors are motivated by the instrumental or expressive needs to engage with other actors in order to access the actor’s resources for the purpose of gaining better outcomes. Instrumental needs are considered to be needs that add value, while expressive needs are the need to preserve what is already there. This assumes that people anticipate and act strategically only driven by these needs. Putman (1996 in Lin 2002) saw social capital as the social life - networks, norms and trust - that enable participants to act together more effectively to pursue shared objectives. These views put social capital as a social asset, something that someone owns and puts to work for gain. Lin referred to “social capital as the ways through which actors gain access to powerful positions by using their connections” (Lin 2002: 29). The latter creating the idea that unequal societal structures influence the social capital someone has, meaning that the powerful can access more resources embedded in social relations. Creating quite a more nuanced view Bourdieu (1986: 248) describes “social capital as the aggregate of the actual/ potential resources which are linked to the possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition.” This idea of mutuality is how Bourdieu distinguished himself from other writers on social capital, together with the acknowledgement that the non-powerful can create equal social capital (Schuller et al, 2000). The second concept that takes the assumption that social networks have a positive role on disaster recovery is social security. One may describe it as an actor having the options to invest in relations to enable choices (Von-Benda-Beckman In Nooteboom, 2003). Through these relations security is established, where the social networks are partly strategically selected and partly shaped through culture, expectations and pressures (Nooteboom, 2003). These concepts thus assume that social networks are a positive asset, but their role in disaster recovery may be greatly influenced by the situation itself. It may also depend on the moment on which the research focused. When reviewing previous research it was noticed that most research focused on the emergency phase, or did not distinguish between phases. In Horst (2008), who investigated families, who received remittances in Somalia, to determine assistance networks, it was unclear as to what phase of the disaster these families were in. Horst (2008) came to the conclusion that the money

- 28. Relation between social networks and recovery 19 received was shared within the community in the refugee camps. This partly represents the idea of altruistic communities. Savage and Harvey (2007), who investigated the connections within a community in Pisco directly after the Peruvian earthquake, argued that the communities support the poorest within them. It illustrated the relevance of community relations, such as neighbours. They found that if a household receives aid from the family after a disaster they are likely to share it with their communities and concluded that the poorest indirectly benefited. This was based on the emergency phase only. Another research that was somewhat unclear on whether the focus was the emergency phase or the recovery phase, investigated the order of social support in Mexico. Here Kaniasty and Norris (2000) tried to link the support to the strength of the relation. It was mentioned that the social support occurs in a crisis situation and they specifically saw that the reliance of disaster affected people started with family, closest friends, neighbours and then acquaintances and the more formal relations. Pelling (2003) argued that periods of emergency are typically marked by high consensus in a community. This altruistic behaviour is aimed at preventing and reducing the suffering. It was noticed that this does not necessarily need to occur as individuals in situations of hardship may withdraw from building up or maintaining widespread social networks and retreat to small tightly knit groups. When looking at the recovery phase, however, Pelling (2003) mentioned that the altruistic behaviour in the community drops during the reconstruction activities as the as the goals of individuals might differ from the goals of the community. Swanson et al. (2009), on the other hand, argued that the informal social networks increase rates of disaster recovery. However, when reviewing their interpretation of recovery it emphasized the period of change immediately following a disaster until one year after a disaster. They do not distinguish between emergency and recovery and they put a time span on the recovery phase of one year. The above written previous research illustrates that research has drawn various conclusions, which might be caused by the different phases in which researcher’s investigate the phenomenon and the multiple interpretations that the term recovery provokes. Quarantelli (1999) reviewed several interpretations of recovery in different research to find common ground amongst them. He concluded that recovery was mostly explained as “the attempt to bring post disaster situations to some level of acceptability, by actions to routinize everyday activities of those whose routines have been disrupted” (Quarantelli, 1999:2) “Some level of acceptability” is open to multiple interpretations, as it may be differently defined and cover a different time span for different actors, such as NGOs, government, companies or affected people. In this research the intention is to look on the longer term recovery process instead of the emergency phase only. The duration of this process is dependent on the households under investigation and this research does not want to put borders as to where it ends. The diverse conclusions drawn by research on this phenomena, led me to believe that a nuanced and more detailed description was necessary. This triggered me in distancing myself from the terms social capital and

- 29. Relation between social networks and recovery 20 social security, as the concepts provide, according to me, a too romantic way of viewing social networks. I argue that being a member of social networks does not necessarily result in support in case of a disaster and assume that vulnerability may influence someone’s need to mobilize the social relations, as well as it may affect the ability to mobilize social relations. Additionally it may influence the actual support, if present, that can be provided. 2.3 Towards an actor oriented perspective As described before, I want to provide a nuanced view on the relation between the social networks and recovery process. Instead of viewing social networks as an asset or form of security that functions in case of emergency, I allow myself to take into account the fact that the social relations do not necessarily provide support. To be exact, a description of the complexity of social relations is needed. I believe that the actor oriented perspective assists me with this. Paragraph 2.3 provides an explanation of the actor oriented perspective with regard to recovery and social networks. 2.3.1 Disaster recovery: an actor oriented perspective As disaster response and thus disaster recovery of a household unfolds itself within the complex interaction of multiple actors with different realities, like described by the mutuality paradigm, a perspective is needed to guide me in investigating these interactions. The basis of the actor oriented perspective that is to bring to the centre “the integration of the theoretical understanding with the practical concerns” (Long, 1992:4) that surfaces through interactions. The places where these interactions take place “the arenas”. The arenas are “the social locations where contests over the issues, resources, values and representations take place” (Oliver de Sardan In Long 2001:59). Within and between these arenas different patterns of social organization occur that result from the interaction, negotiations and social struggles (Long, 2001). The action taken may be influenced by this social organization as Long (1992) argues that action is never taken by an individual alone, but reciprocally constituted with the environment. Through focusing on explaining the social organization, the household’s response might be found. The social organization in the after-math of a disaster can include actors, such as affected people, different NGOs, the church, the municipality and government. Disasters are namely a time where social relations change and new actors appear on location (Hilhorst, 2007). Recovery may then be seen as multiple processes by which actors and their respective networks engage with and (co) produce their personal social world (Long, 2001). These networks may range from family, kinship, “compadrazgo”, to political bureaucratic commercial and recreational connections (Long, 2001).

- 30. Relation between social networks and recovery 21 The various actors involved in the interaction, even if different, have agency. Long and Van der Ploeg (1994) explain this as actors that are knowledgeable and capable within the limits of access to information, uncertainties and other constraints. Instead of looking at affected people to be victims waiting for recovery, this creates the opportunity of seeing affected people as people that have the capacity to enable recovery. The household’s recovery process can then be assumed to come about through the interaction of various actors in the arena(s), while taking into account struggles, disagreements and negotiations accompany this interaction process. As Leeuwis et al. (1990) mentioned, this social process can be influenced by social networks and power relations. This allows for the differences among households as some households might have a better position to access resources and/or obtain knowledge or information by mobilizing their existing social relations and establishing new relations. This means that the actor oriented perspective would put these relations central, which is often been the critique on this approach. Namely it is said to ignore the understanding of the broader social structures and processes in which it is embedded. Having said this, “social action is never made up of a series of detached individuals” (Long, 2001:4). 2.3.2 Social networks in disaster recovery: an actor oriented perspective The actor oriented perspective looks at the creation of a social network as a process in which an understanding is gained of how people create relations and shake off old ones (Long, 2001; 154). The recovery is thus a social process influenced by social networks, which can include the old and new relations. Frerks et al. (1999) already mentioned that the social networks are directly related to how people organize themselves and respond to a disaster. The recovery is shaped through the integration of knowledge of multiple actors and can be influenced by social networks. The networks may explain the different access to resources and information and knowledge that is brought into the “arena”. It is thought that those who are able to mobilize relations may have more opportunities. This does not mean however that “cooperation and the provision of opportunities are necessarily the result of relations” (Long, 2001; 154). The actor oriented perspective does not view social networks as assets that can be used, nor does it assume that a state of security is reached like the terms social capital and social security imply. Through avoiding these terms, a more nuanced view on social networks is expected to surface. It then takes into account that relations might bring certain commitments and obligations which might delay a household’s recovery. It is also a fact that certain commitments might influence the support that can be provided by the members of social networks. As Kapferer (in Long 2001: 155) argues, “the bonds of trust and support do not reside in the realm of abstract moralities or cultural disposition, but rather in strategic management of ongoing relations, exchange contents and social meanings that are