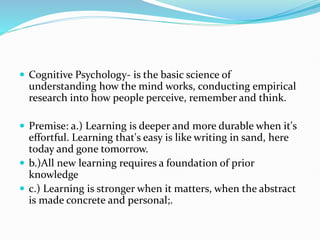

The document summarizes key findings from several books on cognitive psychology and effective learning strategies. Some of the main points include:

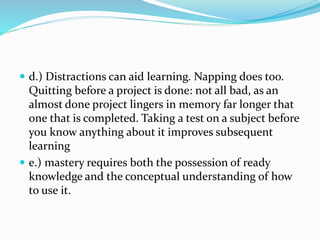

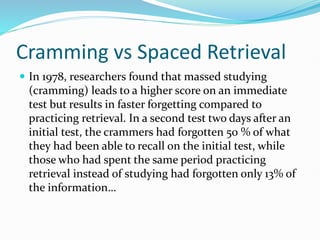

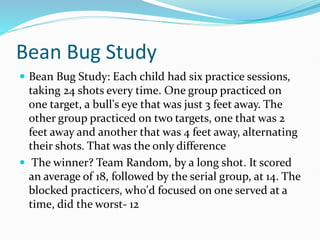

1) Effortful and active learning is better than passive reading for long-term retention. Techniques like retrieval practice, spacing out study sessions, interleaving topics, and self-testing aid in deeper learning.

2) Contextual variations, like studying in different environments or with background noise, can improve memory consolidation compared to consistent conditions.

3) Taking breaks from challenging problems allows for incubation and percolation, leading to insights and solutions emerging after rest. Interrupting tasks also prolongs their memory compared to completing them in one sitting.