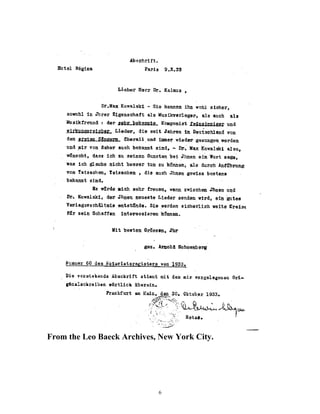

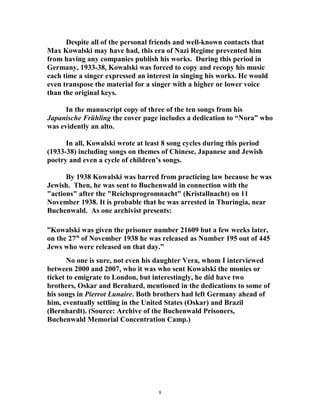

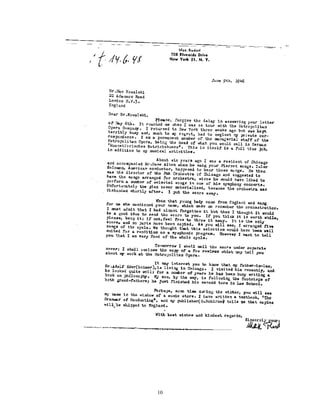

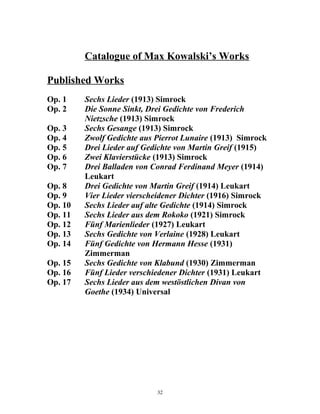

Max Kowalski was a Polish-German composer who lived from 1882 to 1956. He studied law and music in Germany, composing primarily art songs which were performed by famous singers. However, as a Jew in Nazi Germany, he faced rising anti-Semitism after 1933 and was unable to find a publisher. He was imprisoned in Buchenwald concentration camp in 1938 but released. Kowalski then fled to London, where he continued composing but struggled to find publishers for his works, likely due to lingering anti-Semitism or anti-German sentiment after World War II. He composed prolifically until his death, drawing on diverse international influences, but few of his later works were published.

![Unpublished Manuscripts

Op. 18 Sieben Gedichte von Hafiz (1933)

[Op. 19] Japanischer Frühling (10 lieder) (1934-38)

[Op. 20] Vier zusatzliche Lieder (Japanese verse) (1934-37)

[Op. 21] Fünf Jüdische Lieder (1935-37)

[Op. 22] Drei zusatzliche Jüdische Liede (1935-37)

[Op. 23] Zwölf Kinderlieder (1936)

[Op. 24] Sechs Heine-Lieder (1938)

[Op. 25] Zwölf Lieder von Li Tai Po (1938-39)

[Op. 26] Ein Liederzyklus von Omar Khayyam (1941)

[Op. 27] Acht Lieder (Hafiz) (1948)

[Op. 28] Sieben Lieder (Meyer) (1949)

[Op. 29] Sechs Lieder (Hölderlin) (1950-51)

[Op. 30] Sieben Lieder (Rilke) (1951)

[Op. 31] Sieben Geisha-Lieder )(1951)

[Op. 32] Sechs Lieder auf Indischen Gedichte (1951-52)

[Op. 33] Fünf Lieder (George) (1952)

[Op. 34] Sechs Lieder auf arabischen Gedichte (1953-54)

Two Piano Works are not listed: Ein Tango fur Vera (1933)

Ein Slow Fox Trot fur Vera (1933)

I have inserted opus numbers, in chronological order, for these works,

after discovering that Kowalski had himself labeled Sieben Gedichte von

Hafiz as Op. 18 in the manuscript I was given by Kowalski’s daughter.

Bibliography

Cahn, Peter, Das Hoch’sche Konservatorium in Frankfurt am Main,

1980

Goldsmith, Martin, The Inextinguishable Symphony, Wiley& Sons, NY,

2000.

Schaub, H.F., “Max Kowalski”, ZFM cxiii (1952)

Gradenwitz, Peter, “Max Kowalski.” LBI Newsletter. 1982.

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/58c40241-bc39-4615-9dde-9521435f547a-160424065331/85/SUZI_FINAL_DEC_KOWALSKI-editjuan-33-320.jpg)