This document provides an overview of the Stark Law, including:

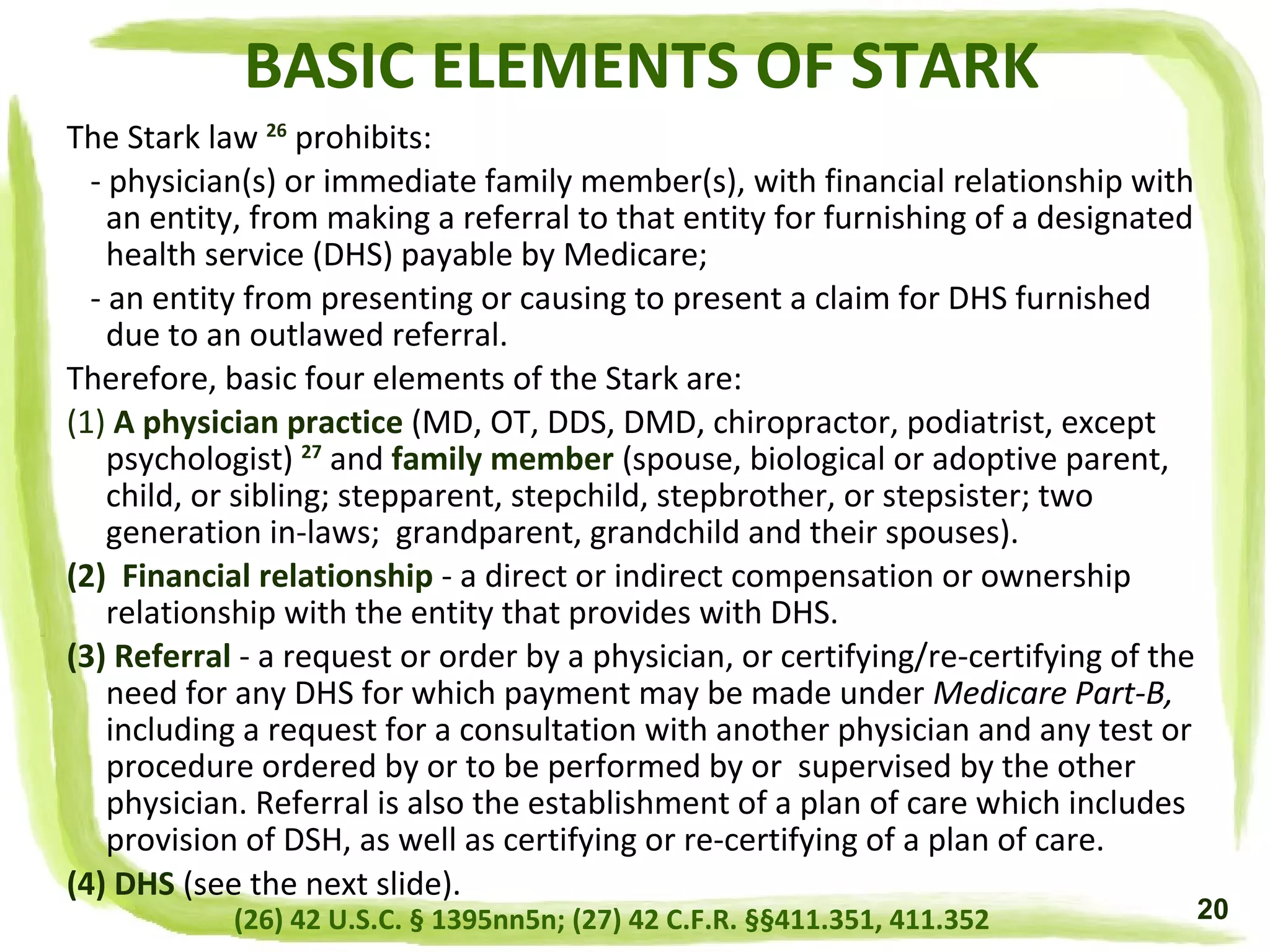

- The Stark Law prohibits physician self-referrals of Medicare patients for designated health services if the physician has a financial relationship with the entity providing those services.

- It addresses questions about who enforces the law, why the law was created, what activities it prohibits, and differences between it, the Anti-Kickback Statute, and the False Claims Act.

- The document outlines penalties for Stark Law violations and lists 17 areas of compliance risk identified by the Office of Inspector General related to healthcare fraud and abuse.

![ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORDS EXCEPTIONS

(1) E -prescribing Exception:

- the DHS entity may provide only hardware, software, or IT and training services that

are necessary and used solely for e-prescribing information

- it may not provide monetary remuneration

- e -prescribing items must be provided by:

[A] hospital to a physician who is a staff member;

[B] group practice to a member physician;

[C] Medicare Part-D sponsor or Medicare Advantage organization to a prescribing

physician;

[D] items and services must be provided in connection with an e-prescription drug

program that meets applicable standards under Medicare Part-D sponsor or Medicare

Advantage plan;

[E] do not restrict a physician's ability to use the items or services with other e-

prescribing or e-health records for any patient;

[F] a physician cannot make the receipt, amount or nature of items or services a

condition of doing business with the donor;

[G] eligibility of physician for items or services and nature or amount of items or

services can't take into account volume or value of referrals or other business;

[H] arrangement must be in a signed agreement that specifies:

- all items and services being provided

- donor's costs of items and services including all electronic prescriptions

- non monetary remuneration covering software or IT and training services needed

and is used to create, maintain, send or receive e-health records.

(93) 42 CFR Sec 411.357w

79](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stark-160918234919/75/Stark-Law-by-Naira-Matevosyan-79-2048.jpg)