Speaking Out Spring 2014 low res

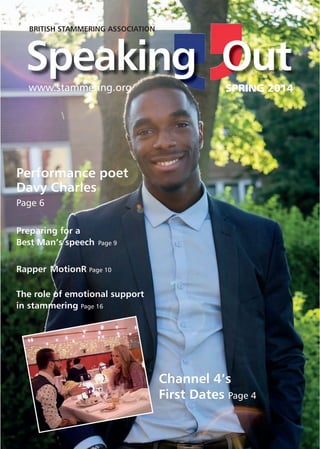

- 1. The British Stammering Association SPRING 2014 1 SPEAKING OUT SPRING 2014SPRING 2014 Speaking Out Preparing for a Best Man’s speech Page 9 Rapper MotionR Page 10 The role of emotional support in stammering Page 16 Channel 4’s First Dates Page 4 BRITISH STAMMERING ASSOCIATION www.stammering.org Performance poet Davy Charles Page 6

- 2. 2 SPRING 2014 The British Stammering Association SPEAKING OUT IN THE CHAIR JOHN M. EVANS Our world is changing fast – not least for people who stammer. Recently, BSA Trustees and staff held a series of meetings to take stock of how things have been changing and to plan our strategy for the next few years. One unwelcome change has been the reduced funding of speech and language therapy services. Owing to the reorganisation of the NHS, in many parts of the country the state of services is now worse than at any time in BSA’s history. At the same time, funding for BSA’s vital and unique programmes for children in the education system has become harder to secure. On the positive side, BSA has been able to make its views known to the Government through the Communication Trust, a coalition of nearly 50 organisations with expertise in speech, language and communication. We hope that BSA’s involvement, by way of submissions prepared with the highest levels of competence and professionalism, will continue to make a real difference to children who stammer. We have also seen two exciting developments which would have been unthinkable ten years ago. First, there is social media. Through the BSA’s Facebook page and our new closed group, over five thousand people affected by stammering have been able to talk to each other – ending the cruel isolation that so many people have experienced. BSA staff moderate these on an ongoing basis, ensuring that the conversation is both well-informed and positive. Members have been inspired to set up their own spin-off pages and groups, including one for parents of children who stammer and even a BSA supporters’ book club. Second, there is the BSA Employers Stammering Network (ESN). With eight large organisations already joined up, it is building momentum, with others joining on an almost weekly basis. We are very grateful to Iain Wilkie of EY and Leys Geddes, the ESN Ambassador (and former BSA Chair), who spearhead this initiative. Organisations are realising that pretending that stammering doesn’t exist works against the interest of both employees and employers. BSA is pioneering ways of helping them talk about stammering productively. We are channelling the wealth of our experience to people in the workplace, helping them to make their voices heard and their talents fully recognised. What’s the strategy? The basic aims of the BSA have not changed. Our goal is still that, at all stages in life, everyone who stammers has better life chances and opportunities for achieving equality with others, and that they receive both understanding and respect. In order to achieve this in our changing world, Trustees see the BSA moving away from simply providing information. A key new aim is encouraging community self-help. We want to link our knowledge and expertise with the new possibilities for bringing people together through the internet and translate that into interpersonal contacts – working to end isolation, helping us all to inform and encourage each other. The ESN fits in well with this. Campaigning hasn’t been forgotten, of course. Trustees want to see the BSA continue to campaign so that people who stammer receive proper understanding and respect, extending our efforts of recent years. The ESN can be seen as part of that initiative as well. I have kept a very exciting bit of news until last. BSA now has a new look, modern website; still packed with the unbiased, accurate information for which the BSA is famous, but now allowing for much greater interaction between us. Interaction and involvement – two key words for the future of the BSA. John M. Evans, BSA Chair Winter 2013Speaking Out-The British Stammering Association We are an Association In the chair as a group of people coming together for a common purpose. In our case, that is to do with stammering. Being part of an association does not mean we all have to see the purpose and ole of the BSA in the same way.After all, stammering affects people differently. Of course there are those of us who stammer – perhaps the bulk of people associated with the BSA. But there are also parents of children who stammer and people living with others who stammer in their families.There are Speech and LanguageTherapists (SLTs) and SLT students. In addition, there are a number of researchers and others who are fascinated by stammering, either because hey want to understand it, or because it is a symbol of their own efforts to communicate better. Someone said to us recently that the BSA“holds all of the stammering community.” How true that is.We work to support everyone affected by stammering, in an open way. We do not favour one type of treatment over another (though we are keen to destroy fraudulent claims of ‘cures’).We do not lay down any rules about the best way to live with stammering (though we do say how helpful it can be to be open about it).The BSA is a place where everyone can learn about tammering, a centre of expertise, recognised as such by everyone. heir personalities, and set themselves to live well with it. We support those who regard their stammering as relatively unimportant, but want to understand t better.We support those who have stammered all their lives, as well as those whose stammering is ‘late onset’ due, for example, to Parkinson’s disease. We upport people who consider they have won a victory over stammering and want to share that victory with others.We support people who are desperately ooking for a new way forwards. Acceptance and friendship are powerful – when we accept ourselves as we are, we give ourselves the power to change. When we accept others as they are, we give them strength to go forwards on their journeys, in the ways that they choose. When we share what we have learnt about stammering and our own Recently the BSA organised a strategy day, when a facilitator came and helped Trustees and staff to envision our strategy for the next few years.This was an mportant day for the BSA and we will be telling you more about it all soon.Some exciting things are happening. One thing that struck our facilitator was the passion that existed within the BSA, and that led us on to think about the source of that passion. Certainly it is a passion to see lives transformed – as we see all the time in self-help groups and at our open days and conferences.Certainly it is a passion to dispel the myths about Registered Charity Nos.1089967/SC038866 Est 1978 Registered Company No. 4297778 15 Old Ford Road, London E2 9PJ tel: 020 8983 1003 fax: 020 8983 3591 helpline: 0845 603 2001 email: mail@stammering.org website: www.stammering.org Vision A world that understands stammering Mission To initiate and support research into stammering To identify and promote effective therapies To offer support for all whose lives are affected by stammering To promote awareness of stammering Activities: INFORMATION AND SUPPORT SERVICE EDUCATION: THE EXPERT PARENT PROJECT RESEARCH COMMITTEE SELF HELP GROUPS TELEPHONE SUPPORT GROUPS OPEN DAYS NATIONAL CONFERENCE MAIL ORDER SERVICE AND POSTAL LENDING LIBRARY INTERNATIONAL LIAISON (International and European Stuttering Associations) MEMBER BENEFITS: Magazine, postal lending library, regular information updates, support groups Annual subscription: £15, concession rate £5 Speaking Out Editorial guidelines Unsolicited material is welcome. Due to space restrictions, not all articles can be guaranteed publication and may be considered for future editions. Speaking Out reserves the right to edit articles for space and/or clarity. Anyone who is contact the editor. For information on advertising Registered Charity Nos.1089967/SC038866 Est. 1978 Registered Company No. 4297778 15 Old Ford Road, London E2 9PJ tel: 020 8983 1003 fax: 020 8983 3591 helpline: 0845 603 2001 email: mail@stammering.org website: www.stammering.org Vision A world that understands stammering Mission To initiate and support research into stammering To identify and promote effective therapies To offer support for all whose lives are affected by stammering To promote awareness of stammering Activities: INFORMATION AND SUPPORT SERVICE EDUCATION: THE EXPERT PARENT PROJECT RESEARCH COMMITTEE SELF-HELP GROUPS TELEPHONE SUPPORT GROUPS OPEN DAYS NATIONAL CONFERENCE MAIL ORDER SERVICE AND POSTAL LENDING LIBRARY INTERNATIONAL LIAISON (International and European Stuttering Associations) MEMBER BENEFITS: Magazine, postal lending library, regular information updates, support groups Annual subscription: £15, concession rate £5 Speaking Out Editorial guidelines Unsolicited material is welcome. Due to space restrictions, not all articles can be guaranteed publication and may be considered for future editions. Speaking Out reserves the right to edit articles for space and/or clarity. Anyone who is unhappy with the editor’s decision should first contact the editor. For information on advertising and rates, please contact the editor. Editor: Steven Halliday Email: sh@stammering.org ISSN: 0143 8891 © 2014 British Stammering Association

- 3. The British Stammering Association SPRING 2014 3 SPEAKING OUT CONTENTS On Wednesday 5th March, BSA member Usman Choudhry was invited to Buckingham Palace to be presented with a Learning Ambassador Certificate by HRH Princess Anne. Usman was recognised after being awarded an Outstanding Adult Learner award from the National Institute for Adults Continuing in Education (NIACE) last year, having been nominated by the City Lit for his efforts in raising stammering awareness. He has helped set up a public speaking group for people who stammer, co-organised two BSA open days, arranged a training course where he works at the Bank of England on interviewing people with speech impediments, and nominated BSA to be its charity of the year, which raised £35,400. He was one of ten award winners selected from the last five years’ awards. Usman said, “At the Palace we were in the Centre Room, from where King George VI stepped out onto the balcony after his speech (and where William and Kate waved to the crowd after their wedding). When Princess Anne (King George’s granddaughter) honoured me, I thanked her. She replied, ‘No, thank you for all the great work you have done.’ Later, she walked round the room and I spoke to her for a few minutes. She seemed very well-informed about stammering and told me about her friend who had quite a bad stammer but spoke fluently when he had to shout when working on his farm. I told her how The King’s Speech inspired me to become a ‘stammering ambassador’.” BSA member becomes continuity announcer NEWS 4 Channel 4’s First Dates 5 The Stammerers Through University Campaign (STUC) STORIES 6 “If I can’t finish a word, how the hell will I finish life?” - A performance poet 7 It’s all in the presentation 8 Stammering in a foreign land 9 Prepare to succeed - Having to do a Best Man’s speech 10 It’s a rap - rapper MotionR THERAPY, SELF- HELP, PARENTS AND RESEARCH 11 My recent experience of NHS speech therapy 12 One small step for Manchester - The Manchester self-help group and advice on starting a group 14 Study on pre-school children draws criticism 16 The role of emotional support in stammering 18 Why so few teenage referrals? OTHERS 19 Stammering gallery 20 Book reviews & wordsearch competition 21 Obituary: Myrtle Aron 22 Readers’ letters 24 What’s been happening on the BSA Facebook page? Photos:MaxMaxwellPhotography As part of its ‘Born Risky: Alternative Voices’ season, Channel 4 recruited a number of people with communication difficulties to introduce some of its biggest shows. Organisers said, “We wanted to give them a platform and normalise the presence of disabled people on TV.” Matthew Oghene was chosen to represent people who stammer, and last December appeared in a primetime slot. Matthew said, “The experience was amazing. They actually wanted to use my voice! I auditioned last September with a script they sent me to read on the day. Then I had to go for a screen test and was accepted. We spent three days learning how to write a script at the Channel 4 headquarters. On the day of filming I arrived very early to get settled in and have make-up put on. The whole experience really made me feel excited about sharing my voice. We don’t often get to hear someone stammering on TV unapologetically.” In the announcement (available to watch online at http://bit.ly/1es9o42), Matthew says, “Hi, I’m Matthew and I have a stammer. Channel 4 have given the mic over to me to introduce the next show: Location, Location, Location. To say it once is hard enough, let alone three times!” Honoured at Buckingham Palace Photo: Channel 4

- 4. 4 SPRING 2014 First dates can be hard enough for people who stammer. Imagine being filmed for a television programme whilst on one! This didn’t seem to faze Paul Thompson, who took part in the Channel 4 show in February. My name is Paul, I’m from Weymouth and I recently took part in a TV show called ‘First Dates’. If you didn’t see it, it’s a reality dating show with a difference. It doesn’t focus on choosing a date; it’s about the date itself. Participants know nothing about the date they have been set up with other than what they look like, from an emailed photograph. I found out about it via a link on the BSA Facebook page, saying that Channel 4 were looking for people who stammer to audition. I’ve always wanted to be on telly and decided it would be fun so I applied. Ten minutes later I had a phone call from one of the producers, Joe, who gave me a brief phone interview (daunting I know, but Joe was very nice and made me relaxed as he knew I stammered). He asked me about myself, what kind of girls I like and how my stammer affects me. He seemed really interested, and a few days later I got the call to go to London to audition. The audition was basically an extended filmed version of the phone interview, with a bit more emphasis on my stammer. It was very relaxed and Joe was eager to get me on the show, and a week later I had confirmation that they wanted me. It was at this point I started getting nervous and excited all at the same time; I suddenly realised that I was going to be stammering in front of millions of viewers all over the UK! Scary. I was worried about my voice and how it would come across. I hate listening to my own voice so I could only imagine what others would think. But I knew it would be a good thing to do as it would put me outside my comfort zone and also hopefully raise awareness of stammering. I wanted more people to see how the condition affects us and how best to talk to somebody who stammers. Filming I went up to London to record the interview that would be broadcast, which repeated a lot of stuff I had said at the audition. They also asked what I was expecting from the date. They only showed a tiny bit of what was actually recorded, though. The dates themselves took place in a posh London restaurant. A bit smarter than what I’m used to; it was no Wetherspoon’s beer and a burger night! Being filmed for the show was weird. There were cameras everywhere; on the walls, the ceiling, by the bar, in the toilets and outside. Everything you did was captured, there was no escape! But after a while I kind of forgot they were there. The first date was with a writer called Christine. I was really, really nervous beforehand. Not because of the usual first date nerves (well, a bit) but because I wasn’t feeling well and I know that this makes my stammer worse. I had been stammering quite badly all morning, and I was worried I was going to come across like an idiot. It also stopped me saying a lot of things as I knew I was going to stammer so I really held back my conversation at times. The way the date was edited made Christine come across badly. She got a lot of abuse online afterwards with people calling her condescending, but she wasn’t really like that at all. They can’t show the whole date, so they pick the bits that keep viewers interested. Unfortunately this was me having a bad stammer day and Christine looking like she was being rude and patronising. Anyway, I thought she was really interesting. She did talk a lot but I didn’t mind as I was enjoying not talking so much, if I’m honest. She did talk over me a few times and tried to finish my sentences, and I did try to explain it wasn’t helping. I had a bit of an emotional five minutes in the post-interview, though, where they filmed me talking about how it went. I had a little cry because I was annoyed that my stammer was bad and I wanted the date to have gone better. We had a fun time, though, and agreed to be friends, with a high-five sealing the deal. For a few days after filming, I was quite upset with myself over the way it had gone. I was worried that I was going to come across as a bumbling, crying idiot and people were going to laugh at me. I thought my stammer was atrocious and I nearly called to ask them to remove the emotional bit. However, producers kept phoning and emailing me to check I was alright, which was lovely. They assured me that it would be edited in such a way that the viewers would warm to me and Channel 4’s First Dates Photo:CourtesyofTheDorsetEcho The British Stammering Association SPEAKING OUT Paul and second date Kathryn. (Photos: Channel 4)

- 5. The British Stammering Association that it would all be alright. Second date I also featured in the next episode, where my second date was a down-to-earth, funny Irish lass, Kathryn. She was great. We got on famously, laughing and joking about all sorts of stuff. I was more relaxed with Kathryn but that probably had a lot to do with the fact that I wasn’t feeling ill this time. I even managed to get my BSA wristband into the conversation as well. Well, she noticed it and asked what it was. The stammer didn’t seem to bother her at all; she even said she liked it and that it was more like an accent than anything. “An accent that takes half an hour to say a word,” I believe was my reply. Unfortunately the date was to go no further either; Kathryn only wanted to be friends. I think the geographical distance between us was a big decider in that. Looking back, neither date was really my type anyway. I was so nervous before the first episode aired that I hardly watched myself at all. However, all my worries soon disappeared as the public reaction came flooding in. I couldn’t believe it. The amount of new Twitter followers, Facebook friend requests, messages and tweets was unbelievable! My phone was going crazy. Nobody had a bad word to say about me. I was completely overwhelmed with positive responses. It took me till 2am that night to sift through all the online correspondence. All my friends tuned in and left me lovely comments. I had random ladies from all over the country saying how they would love to date me and how brave I was for going on the show. It was mental. I even had a marriage proposal! (Not sure how serious that was, though). I get noticed and chatted to all the time when I’m out. Most people just want to say “well done” and talk to someone who’s been on the telly, but it’s still nice. A lot of the response has been from fellow people who stammer, saying it has given them confidence to do more challenging things, which is great. I’m glad I could be a kind of role model. Overall, I had a great time on the show. It was a wonderful experience and I met some awesome people in the cast and crew. I would definitely do it, or something similar, again. Watch Paul’s appearances on First Dates at http://bit.ly/1fEsjrI. Follow him on Twitter: @paulamahol. “I was worried that I was going to come across as a bumbling, crying idiot and people were going to laugh at me.” SPRING 2014 5 SPEAKING OUT Undergraduate Claire Norman introduces her project that aims to support students at university. Attending university can be truly beneficial and offers priceless opportunities and life skills. However, many students feel that their stammer prevents them from ‘coming out of their shell’ and obtaining the confidence required to achieve these. Hence, it can be assumed students who stammer find it difficult to develop in preparation for the working world that faces them when they graduate. I am a final year undergraduate studying French Studies at the University of Warwick and I have felt for a while now that there is little awareness of stammering within the university environment. In comparison to other, more evident disabilities, such as dyslexia, there is insufficient support for students who stammer. There was obviously a gap in the ‘market’ as far as I was aware. So I decided to change that. The Stammerers Through University Campaign (or ‘STUC’, emphasising the possible feeling of being trapped by having a stammer) is a concept that I created with the aim to bring together students and staff who stammer in a network where they can discuss issues and possible resolutions. It is a social enterprise supported by the University of Warwick in partnership with UnLtd and the Higher Education Funding Council for England and Wales. Thanks to the support of a departmental staff member at the university, I was made aware of the Social Enterprise Award, a scheme that offers funding for schemes that aim to support the wider community. Having posed my idea to a panel of judges, I was awarded £500 to get the scheme up and running. I held a focus group at my university in February for those affected by stammering, in order for me to gain an insight into what concerns they currently have. My aim is to hold a seminar in October to address the issues raised in a non-judgemental and supportive environment, when I will return as an alumnus to run it. The seminar will include external speakers, people who stammer at Warwick, staff, students, university personnel, Psychology and Applied Linguistics researchers, and many more. As far as education is concerned, I wish to develop this project to help students affected by stammering by extending it eventually to other universities and broadening the potential outreach. I want to provide students with a greater insight into how going to university doesn’t have to be the most daunting experience they will experience. It is vital to me that the message is emphasised that having a stammer does not have to prevent us from reaching our full potential. With the support of the BSA, together with the University of Warwick, I am certain that this campaign has the potential to succeed and prove beneficial to so many people. If you are a student and would like to get involved, go to www.stuc-uk.org. Follow the campaign on Twitter: @ STUC_UK. The Stammerers Through University Campaign (STUC)

- 6. The British Stammering Association SPEAKING OUT 6 SPRING 2014 Davy Charles tells us how taking up performance poetry has transformed his confidence. Time and time over, in the hope that chance would side with me, I went against insurmountable odds and came up empty-handed. Throughout my life I have tried many different ways of combating my stammer, but it wasn’t until I started doing performance poetry that I started thinking about it in a new and unusual way. Growing up on a tiny Caribbean island where people spoke both English and French, having a stammer did nothing but double the number of languages I couldn’t express myself in. My schoolteacher pretty much forced me into seeing a speech therapist. Going for therapy meant crossing the island on my own - I was only nine. But I was met with sheer disappointment, all my expectations flattened. I was given a few speaking exercises and told to breathe more. Where was the magic fix? None of it sunk in and after a dozen sessions I quit. When we moved to England in 2001 I had the chance to reinvent myself. I could leave the old me behind, stammer and all. I began making conscious efforts to speak fluently. But when I blocked, my self- awareness heightened, in turn exacerbating it and creating a cycle of tortuous mental exertion. But I kept pushing, putting myself in situations I hated, like speaking on the phone (I took a job in a call centre). I hoped with each confrontation my speech would improve, but it didn’t. There it was, like an unwanted extra limb forcing people to find somewhere else to look as it fumbled into the conversation. Unexpected inspiration Looking for a new creative outlet and challenge, I started doing performance poetry in 2013 through what I can only describe as divine intervention. One restless night I woke up at 4am and knew immediately I wasn’t going back to sleep. Lying there, it came to me; the first lines of what I later knew to be a poem, a poem I later called ‘The Story Of Your Opinion’, which had probably been buried inside me my whole life, as I’ve spent so much time worrying about others’ perception of me. I found a poetry event and went along, performing my poem ‘Frankenstein Love’. I remembered to compensate for my stammer; when I felt a block coming, I simply spoke faster and a lot of that poem was mostly inaudible through a combination of nerves and difficulty pronouncing the sounds, syllables and rhythms. I later joined a group called Gorilla Poetry. We have just about every type of poet, from classical to performance-based poets, even MCs. Styles, tone and content vary wildly, offering me a wealth of inspiration. Every time I think I’ve progressed and expanded my range, we get someone new performing who completely changes everything about what I thought poetry could be. Performing quickly becomes addictive. The feedback I get from audiences is something I can no longer live without. Rhythm I realised that it’s all about rhythm. The way I spoke fluently by connecting to the rhythm of the poem was symbolic of how each of us has our own rhythm, our own pulse and once we discover it, once we discover ourselves, we can then tap into our full potential. I realised I didn’t believe in that still voice inside. Self doubt, shyness and lack of conviction constantly shouted over it. I realised that breathing is listening. Speaking is a call and answer. That still voice calls, you inhale then answer by breathing out. Thanks to this new understanding of myself and my impediment, my speech is now much improved, but still far from perfect. There’s infinite room for you to grow, once you lose that negative clutter. Self-belief 2013 was one of the best years of my life. I won the top prize at the Word Emporium in Leeds, part of the Love Arts Festival and I also became Grand Bard of Gorilla Poetry. As Grand Bard of the collective I host its open mics and ‘slams’, which requires a lot of quick thinking - I’m getting better at it. At a recent slam, one performer got very nervous and left the stage after delivering only two lines - she was visibly distressed. In these tense and delicate moments I get nervous too and when I went onto the mic I stammered quite badly in trying to move the show forward with sensitivity. I’m now working with local film companies to create a series of spoken word videos which I will distribute online and through social networking. I can’t describe what all this has done for my self-belief – not just as a poet, but as a human being. All of us have a voice, but now I know I have something to say. When I sit and properly reflect on how much I’ve grown in terms of confidence and the performance of my poetry, I get frightened. I used to look at confident people and think, ‘I’ll never be that comfortable in front of everyone, I’ll never be so calm and collected’. Now, just a year later, my nerves are virtually gone. Virtually... Watch Davy performing ‘Sometimes I Stutter’ at www.davycharles.co.uk. He will feature in a BBC Radio 4 documentary on Thursday 17th April at 1:45pm, available on iPlayer after that. “Each of us has our own rhythm, our own pulse and once we discover it, once we discover ourselves, we can then tap into our full potential.” Davy’s trophies “If I can’t finish a word, how the hell will I finish life?”

- 7. The British Stammering Association SPRING 2014 7 SPEAKING OUT Most of us have been through the nightmare of having to give a presentation. 18 year-old Jodie Chapman talks us through her recent experience and gives advice on how to cope with them. In January I had to do a presentation at college on an enzymes experiment we did in Chemistry. In it we had to talk about our aims and predictions for the experiment, the equipment we used, the methodology, results and then give an evaluation and a conclusion. We had ten minutes in which to do it. Being an unconfident person (because of my stammer), I was very nervous about it. On the morning of the presentation I felt really sick. On the way to college I was shaking and had a full sweat on. On the bus I did actually think I was going to throw up! My heart was racing and I simply could not relax. I met up with my friends in the lesson beforehand. One of them asked how many slides I had included, and was panicking because I had done more than her... which made me panic because I thought I had done too many! I told them that I was really worried. I was scared because I was desperate to get a distinction for this assignment, and for that you have to present with ‘confidence and polish’. They told me I was going to be absolutely fine. They said, “Just think, you’re getting it done and out the way today, so you won’t have to do it on Friday,” which made me feel a bit more at ease. I had emailed my teacher the day before, telling her how nervous I was. She suggested I pretend I was talking to an empty room, which helped. She also gave me an extra minute to do it in because of my speech. Once I got to the classroom I felt so scared. My heart was racing and I was having a cold sweat. Normally I would have a homeopathic pastille to help me calm down before doing these types of things, but I didn’t have time, as my teacher arrived shortly after and asked if I was ready to do the presentation. She reassured me and said I’d be fine. She then told the other students that they could work on their computers or watch me, but either way they HAD to be quiet. This took the pressure off a bit. She also told them to be nice to me (I think she was referring to my stammer and that they shouldn’t laugh if I got stuck on a word). Then I remember her saying, “Whenever you’re ready,” a sentence I was dreading. In the moment I had a dry mouth and throat throughout and a sweaty back. I didn’t think I would get everything said in time. I sped through it and stammered quite a lot in the process; I think the speed caused me to stammer more. But for the first time ever I actually ignored everyone else and imagined I was just talking to the teacher. When I did block, I either concentrated on reading from the slide or the flash card. I knew I couldn’t just read from them; I had to make eye contact with the audience, which I did. However, my teacher said that if I wanted to, I could look out the window while speaking. I really didn’t care about my stammer at the time, because I was just so eager to say my stuff and get it out the way. When I finished I remember my teacher saying, “I bet you’re glad it’s all done now. It wasn’t that bad, was it?” It was definitely the best presentation I’ve ever done, and the one that I’m the most proud of. I felt so relieved. As it turned out, I got no response (good or bad) from the other students when I stammered. Tips If anyone has a presentation coming up, I would say that it helps to talk to someone about it. Tell a friend, family member or teacher how you feel and what you think will happen. They’ll be able to reassure you that it will be fine. Ask your teacher if you can do your presentation first out of everyone in the group, which will mean you won’t have to wait and worry. If it’s a timed presentation, ask for extra time. If you see a speech therapist, ask them for coping strategies. My therapist reminded me to use ‘soft onsets’ and to say the first sounds really slowly to help the words flow together better. Before the presentation, try telling your audience that you have a stammer (if they don’t already know); this will not only reassure them, but you will feel a bit more relaxed because they are aware that you might stammer. Also, try and sound confident in what you’re saying. Practice the presentation until you know it inside out. Try and relax the night before. Take a hot bath and listen to music. But the main thing is to have fun whilst you’re up there. Speak from the heart. It’s really not the end of the world if you stammer, and people will not think less of you. And do you want to know what grade I got for my presentation? A distinction! “Then I remember my teacher saying, ‘Whenever you’re ready,’ a sentence I was dreading.” It’s all in the presentation

- 8. 8 SPRING 2014 The British Stammering Association SPEAKING OUT Lecturer Grant Meredith shares his experiences of teaching in China and explains how his stammer wasn’t as big a barrier as he feared. In 2012 I was invited to lecture a course on effective communication skills, team work and oral presentations in China as part of a partnership commitment with my own university in Australia (University of Ballarat). What followed was an eye-opening adventure in terms of fluency, respect and the use of a Western teaching method. At first I was a little apprehensive in accepting the offer. It would mean nearly a month away from my family and I only knew one phrase in Mandarin. I was also unsure about how they would accept my overt and at times very severe stammer. So off I travelled to tropical Shaoguan University in Guangdong province. Upon arrival I was greeted by my minder and I found that I had to slow my speech rate down to half my normal speed for him to understand what I was saying. I spoke too fast and my accent was very thick. This was a challenge in itself because I’m usually a very fast talker. Slowing down certainly smoothed my speech out and I found myself stammering less. The next challenge was communicating with my new students. After settling in I was introduced to the academic hierarchy who were all very interested in my thoughts and teaching methods. The next day I would meet my students from amongst the 25,000 who lived on campus. I was also told that I would stick out, being the only ‘white person’ there. Cultural differences The next day came and I entered the lecture hall. In front of me was a class full of focused students. They had all learnt English during their school years but still their conversational skills were very mixed. After teaching for three hours I asked them for some feedback concerning how well they understood me. Now, I was stammering overtly, loud and proud the whole time, but to my surprise it was not an issue. Most students said they had never spoken to a native English speaker and were having trouble understanding my accent. My accent was too heavy for them but my stammer didn’t raise a mention. These students had grown up in a very respectful society where lecturers are seen in very high regard. The physical characteristics of how I spoke didn’t bother them at all. Not a single one stared, laughed or even seemed to acknowledge it. It took the students a full week of daily classes with me to be able to understand most of what I was saying. Surprisingly they were finding it more difficult to get used to my Western teaching style. They were confused why I smiled as I taught and at how animated I was. They were also taken aback when I asked them questions. Usually a Chinese lecturer would not ask the class questions or interact so openly with them. It was so interesting to live and teach in such a respectful culture where my stammering was not an issue. Another challenge was learning how to toast. Often I would be asked out to dinner by members of the university hierarchy. These dinners were amusing because most of the time there was no interpreter and the hosts spoke little, if no English. In that case my hosts would interact fully with each other and I would smile and eat. However, the problem came when I was required to toast individuals and the table. Early on I was told that I should toast everyone to my right-hand side at least once every meal. I am still unsure if that was in fact custom or simply a ploy to get me drunk. The problem I found was not conducting the toast but trying to think of something different to say each time. At some meals I gave more than 10 toasts and I found myself getting very good at it and using phrases that would make a politician proud. The big one My final big challenge was conducting a public lecture to the university about research that I had been working on. Invitations were sent out to all interested parties and on the night I was treated like a star. I entered the auditorium and was greeted by a crowd of over 400 applauding staff and students, all of whom had voluntarily come to hear my speech. I was ushered to the stage and asked to sit down at a table with a microphone on it. I said, “Sit down? I don’t know how to lecture sitting down!” So I stood up, walked around, smiled and even showed a little humour as I presented. All along I was stammering, grimacing and blocking uncontrollably, but with confidence. I received a standing ovation and some remarked that it was like meeting Steve Jobs! I was swamped afterwards by people wanting their photograph taken with me. A few weeks later it was time to fly back to Australia and back to my family. It was an amazing experience and it was such an embracing culture. I was blocking, prolonging and repeating the whole time and yet it was not a concern at all. “I received a standing ovation and some remarked that it was like meeting Steve Jobs!” Stammering in a foreign land Grant in action Grant (back row, third from left) with students

- 9. The British Stammering Association SPRING 2014 9 SPEAKING OUT Being asked to be Best Man at a wedding can be a proud moment... until you realise you have to make a speech. Trevor Bradley explains how he prepared for his by working on changing his mindset. Appreciation. Fear. Avoidance. All of these thoughts flooded into my mind when my grandson Stefan asked me to be Best Man at his wedding within two years. Plenty of time, I thought, to prepare a speech. What would I say? What couldn’t I say? How would I or my audience react when I stammer? At the age of 62 I have acquired what I call a ‘toolbox’ of therapies, some useful, some not. Luckily I am a member of the Doncaster Stammering Association (DSA) self-help group, with Chair Bob Adams. There, we practice speaking circles, a great aid for overcoming anxiety of public speaking. Both the audience and the speaker have mutual respect and what you say is not the ultimate aim. You don’t need to be funny or interesting. In fact you don’t need to say a word, it’s the connection of eyes and minds, the giving and receiving. It’s OK to be you. At the end the applause you receive from the audience is a thank you for being you! This positive outcome was what I needed to focus on, not the need to be fluent. Positivity Understanding the way I speak to myself is important. If I keep thinking negative thoughts then what outcome will I have? I had the opportunity to add to my toolbox by attending a two-day intensive course organised by Hilary Liddle and Cheryl Orr at the Doncaster Speech & Language Therapy Department. In the group we discussed icebergs. No, not the ones that can sink a ship, but the ones that float around in our subconscious, threatening to sink ourselves. What we show on the surface is not always mirrored below. I have always tried to hide my stammer by constantly changing words, pretending to forget someone’s name, avoiding taking risks in socialising, and always taking the back seat. At the end of the session we made a list of what feelings lie beneath the surface. Mine included humiliation, shame, fear, anger, and thoughts of ‘I’m not good enough’. So on the wedding day all I needed below the surface was a positive attitude to the way I communicate. My main anxiety was how I could make the speech as amusing as possible. I practiced it in front of the DSA but didn’t get many laughs. In fact it read like a short autobiography and I wasn’t pleased with the result, although the group said it sounded OK. I needed to find additional guidance for my toolbox and found Barbara Gomersall, a Neuro-linguistic Programming (NLP) practitioner whose course I attended in 2008. She recommended changes such as reassembling the words to make it punchy, like stand-up comics do, and to anchor feelings of fun, pleasure, relaxation and speaking with expression. Now my iceberg contained positive thoughts - no longer ‘is this good enough?’. With this in mind I practiced at home using three mirrors: one placed in the centre, one to the left and one to the right, making eye contact with each and visualising people laughing with me, not at me when I spoke. I also used a voice recorder. One last technique Hilary taught me was voluntary stammering, the behaviour I spent most of my life concealing. Far from being embarrassing on the day of the wedding, it proved to be liberating. Before the speech I felt happy to be among family and friends but I waited nervously for my time to come. The speech The time had finally arrived - the Best Man’s speech. Nervous yes, but my iceberg beneath the surface was full of positives. I unfolded the pieces of paper from my pocket. The speech was there in front of my eyes. It seemed a blur of words I could not focus on, just the memory of many hours spent practicing speaking and gesturing at the correct moments. The fuse had been lit. Nothing could stop it now. “For those of you who don’t know me, my name is T-T-T-Trevor and I am Stefan’s granddad. You may have noticed that I sssssssstammer. The good news is, if you don’t hear me the first time you’ll hear me the ssssssss... 8th time.” Bob gave me permission to use one of his quotes to advertise my dysfluency so that I could laugh at myself in a positive, accepting way and to allow the audience to laugh with me. I relied on physical and vocal memory to carry the performance and I ended with: “And finally, will everyone stand and toast Stefan and Lauren.” Applause rang out around the room and many came over to congratulate me. At the end I was happy; relieved, with a sense of accomplishment that I gave it my best and my best was good enough. Without the help of the four people mentioned I would not have had the inner belief that I could communicate effectively in the public arena. You could say I had made myself bulletproof from the fear of failure and being judged. I had practiced to succeed. “The speech was there in front of my eyes. It seemed a blur of words I could not focus on. The fuse had been lit. Nothing could stop it now.” Prepare to succeed

- 10. It’s a rap Ruben Sewkumar, aka ‘MotionR’, talks about being inspired to take up rapping and how music has helped him with his stammer. I have had my stammer for as long as I can remember. I am 17 now and having a stammer does come with challenges on an everyday basis. For most people, ordering food, talking out in public and making jokes are all normal things to do. But with a stammer all of those things are difficult. Let me take you back three years ago to McDonald’s, where I was ordering an egg Mcmuffin. I just couldn’t finish the last part of the word and was struggling to get the sound out. The cashier looked at me, laughed and said, “Next please.” At that point my confidence and self-esteem sank and I didn’t try again. My high school life wasn’t easy either. I was picked on frequently and was somewhat of an outcast because of my stammer. I didn’t really talk to anyone and no-one really understood my condition. I hardly had a social life until year 10 or 11, when I met a small group of people, whom to this day I’m still friends with. Inspiration I started rapping at the age of 11 or 12 after listening to Eminem. He inspired me to start writing myself and remains my biggest influence. I never took writing seriously back then and just wrote when I wanted to. But I found out that I could rap and not stammer at all, which was amazing; it not only helped me express how I felt, but it gave me confidence and I have been rapping ever since. I don’t know what it is about music, but it helps me. It is hard to break out in the music scene when no-one wants to give you a chance, but I write and rap to get my feelings out and to express myself. I bought myself a microphone and I record, mix and produce my own songs all in my bedroom on my computer. I’m not sure where the name ‘MotionR’ came from - I just wanted my initial in it! With regards to the creative process behind my music, I write whatever comes into my head. I always carry my notepad with me wherever I go, or I just type lyric ideas onto the ‘notes’ section on my mobile phone so that I don’t forget them. All of my songs have a meaning and a message behind them. Some of my songs are based on my stammer, songs such as ‘Dear Destiny’ and ‘Famous’. Here’s part of a verse from ‘2 Aspects Of Life’: “Take a second, close your eyes. Just imagine living life not uttering and people not understanding that you’re ssssssstuttering! I’ve grown up with this disorder but who would have thought I could get my words out on a tape recorder? See, rap has helped me and I feel obliged to give something back.” The response I am getting from my friends and peers at college and others around me for my music is pretty positive; everyone is supporting me. I haven’t performed live yet but there are chances to do so at college and I will be taking them (with a bit of confidence, ha ha!). I would love to perform and spread the message that even with a speech disorder you can get past it; you can make something of yourself and follow your dreams. Therapy In 2012 I joined a speech therapy course at The Michael Palin Centre in London, where I was taught different techniques for controlling my stammer. One was called ‘the freeze’ and helped to overcome a block: when you stammered, you had to stop and try again. Another technique called voluntary stammering, where you would choose to stammer, helped a lot too. I was doing well with my speech after the course; I was going out, ordering food and taking leaps that I never knew I could take. Recently, though, it has reverted back to the way it was before the speech therapy, and has got to a point where I ask my friends at college to order my food for me. It’s pathetic and patronising, I know; I should be able to order my own food! Some days I’m fluent but on other days talking is a nightmare. College has been amazing, though. I have just done three presentations and they all went well. All my classmates are supportive and I couldn’t ask for a better place to study and have a social life. No-one really understands what it’s like not to be able to say what you want, or how it makes you feel. They can only imagine. People may laugh and say things, but we’re all the same at the end of the day. Music, and rap in general, has really helped me deal with my stammer and I don’t honestly know what I would do without it. Listen to ‘Dear Destiny’ by MotionR: http://bit.ly/1jaCdW9. (Please note that several of his other songs have explicit lyrics). Follow MotionR on Twitter: @ Motionrmusic. “I would love to perform and spread the message that even with a speech disorder you can get past it; you can make something of yourself and follow your dreams.” SPEAKING OUT 10 SPRING 2014 The British Stammering Association

- 11. Ben Hewett shares his progress after returning to therapy after over twenty years, and highlights the growing threat that NHS services are under. I didn’t start stammering until I was eight, so because I spoke fluently up until then, my beginning to stammer constituted a change in the way I spoke - unlike those who stammer from the time they can talk - this served to emphasise my stammering to everyone who knew me and draw attention to it. I didn’t understand and greatly feared it. I was taken to a speech therapist. This experience - which consisted mostly of reading exercises and being repeatedly told to slow down - was of little help. In hindsight, I believe that the period of time during which I spoke fluently reinforced the idea that fluency was the norm and thus stammering was abnormal and should be hidden at all costs; to return to fluent speech was all I wanted and nothing less than this would do. My single-minded desire for fluency (and my hatred of stammering) persisted throughout my teens and twenties, during which I struggled to achieve anything I wanted to. I left school after my GCSEs, worked in various unfulfilling jobs for eight years (hiding my speech and the impact it had upon me as best I could) before finding the courage to go to university. There I found some confidence, both personally and academically, which gave me hope. However, upon leaving university, my speech deteriorated and my confidence nose-dived. Return to therapy At this very low point, I decided to seek speech therapy again. I had little optimism that it would help (given my previous experience) but decided it had to be worth a try as the alternative was far worse. Implicitly, I wanted fluency but this was quashed in the first session when I was told - in the kindest possible way - that there is no cure and that I was likely to stammer, in some capacity, for the rest of my life. This was hard to take but, in a sense, a degree of relief set in: maybe I didn’t need to struggle anymore. This sense of relief - resignation, in all but name - was soon replaced with optimism that even though I may stammer for the rest of my life, there were things I could do to manage it. Much of therapy to date has centred upon identifying my stammering behaviours - my avoidances, as well as what I physically do when I block - and desensitising myself to the act of blocking. To allow myself to feel the full force of a block (which were often uncontrollable) and to not panic and avoid the block was a crucial step for me. I won’t sugar-coat it: desensitising myself to stammering has been one of the hardest things I’ve ever done but it’s also one of the most empowering as the sense of acceptance, and therefore of control, was genuinely attitude-changing. This sea-change in attitude and the boost in self-belief soon resulted in another important change: I realised that my speech-related anxieties derived from my own negative relationship with my stammer, rather than from anybody else’s negative reaction to it. This further increased the sense that my stammer was something which was mine and as such, it was something that I could change. I started working through Block Modification Therapy, an approach premised upon the idea that I had a choice as to how I reacted to a block. Whereas before, my reaction was to struggle and ‘push through’ the block, this taught me to do the opposite: to stop, identify where the block was, reduce the tension and to slowly and calmly utter the word. I soon realised that I could block and still utter any word with minimal struggle; blocking didn’t have to mean I couldn’t say that word. The most significant benefits I have gained from therapy have been the changes in belief about my speech. I believed that stammering was something which happened to me, and was to be avoided. I now believe it is something I do and something which doesn’t have to be struggled against or avoided. My outlook has changed completely. I still stammer and find it difficult at times, but I now have a few skills to manage it in order to lead the life I want to lead. Therapy cut short Unfortunately, however, after almost nine months, my therapy was prematurely cut short due to cut-backs at the Trust which provided the adult stammering service. This news was very distressing as I was several months away from completing the therapy plan set out for me and I felt very much like I’d been abandoned. The dire situation in Birmingham with regards to adult stammering services prompted the BSA to launch an awareness campaign in the city, involving local MP Jack Dromey, giving me the opportunity to be interviewed by a local newspaper in order to raise awareness of the issue. The interview - a telephone interview of all things! - went really well and, in a way, the opportunity to assist the BSA in this way helped me to realise how far I’d come in my stammering journey. Thankfully, whether due to the pressure of the interview or not, I’m being transferred to a neighbouring service and will continue my therapy there. The British Stammering Association SPRING 2014 11 SPEAKING OUT Ben in The Birmingham Mail My recent experience of NHS speech therapy

- 12. The British Stammering Association Max Gattie introduces the Manchester Stammering Support Group and gives tips for setting up a group in your area. Being around others who stammer is an unforgettable, if initially awkward, rite of passage. As in a hall of mirrors, manifestations of oneself are reflected back multifold. Several stages of the stammering odyssey are seen simultaneously. Experiences you’d viewed as unique turn out to be not so extraordinary after all. As these commonalities crystallise, you gain insights which would have been impossible to obtain otherwise. The Manchester Stammering Support Group meets every fortnight. We have a private room at a further education college in the city’s Spinningfields business district. After a formal session lasting a couple of hours, we’ll continue at a bar or pub nearby. There are extra-curricular activities too: Christmas parties, karaoke nights and speed dating evenings have all featured. Members are experienced in a range of therapies, and some have even done research into stammering. We also have trainee or qualified Speech and Language Therapists in attendance. With a growing member base, the group is going strong. But it wasn’t always this way. Seven years ago, there was no group at all in Manchester. Starting a group may be easier with NHS help In 2007, after a series of one-to-one sessions at Manchester Royal Infirmary, I’d reached the stabilisation phase of speech therapy. My therapist, Rachel Purcell, suggested I attend a support group. I was keen to participate but Rachel only had contact details for one group member, who had moved out of the area. Nothing was running. We would have to start anew. Recruiting from her client list, we set up a group at the hospital. Initial meetings were held monthly, with four or five attendees. We continued in this way for about a year, shuttling between whatever rooms were available. After a few memorable sessions amidst learning skeletons and saline drips, we decided to move away from the hospital environment. This took us as far as a pub over the road. Soon after, I moved the group again, to a bar near my flat. This might sound selfish, but at the time I was the only regular attendee and thought I might as well make it easy on myself. It helped that I lived next to a major transport hub in the city centre, easy to get to from any part of Manchester. The geographical advantage was, in my opinion, essential in enabling the group to grow. Meetings continued like this for a couple of years and others started attending regularly. Growing the group beyond five or six was still difficult, though. Location and management structure are important At around this point, one of the regulars suggested we move the group, after hearing about a social welfare project that could provide us with a meeting room and minimal funding. A drawback was that we’d be on the outskirts of the city, at least two bus journeys away for most members. It was an attractive opportunity, though. We’d had difficulty finding a private room in the city centre, and had ended up in quiet corners of pubs. This is far from ideal. It can be off-putting for first-time visitors who are self-conscious about stammering. It also precludes many activities, such as guided relaxation or prepared speeches, which would otherwise have been worthwhile. With these limits on meeting structure, it was all too easy for sessions to end up as a talking shop, covering the same old ground every time. Additionally, the organisation was too loose. I was sending out reminder emails for each meeting, but after several years was keen to step away from the day-to-day running. I didn’t have time to work out a detailed programme for each meeting so I was enthusiastic about shaking up proceedings and moving to a more formal setting. Before going on, it’s worth mentioning that I was concurrently gaining a lot of experience with group leadership elsewhere. I’d acted as club president, and then area governor, for the local Toastmasters public speaking club. As such, I had a good insight into the workings of professionally-run groups. I also knew how difficult it was to find free rooms in the city centre. This wasn’t a problem for Toastmasters, which could rely on 20 attendees at each meeting, and a member list of 30 who paid fees twice yearly. But the stammering group was nowhere near this size, and charging for attendance was unfeasible. So, we moved to the new venue. The member who had suggested this insisted on a rigid hierarchy, with himself in command. This came as a surprise to long-time members, one of whom walked out early on after being chagrined for lack of attention in a secretarial role. Attendance dropped, although it was hard to tell if this was due to the location, or the new structure. After a few more meetings, the member who had “I quickly found myself making friends, whom I’ll keep for the rest of my life.” One small step for Manchester Max (left), Christmas party, 2012 At the NHS facility, complete with learning skeleton (Max, second left) 12 SPRING 2014 SPEAKING OUT

- 13. The British Stammering Association SPRING 2014 13 SPEAKING OUT initiated the move dissolved the new group without consultation. This was our biggest test yet. No meeting room, a scattered member base, and nothing scheduled. Try to let the members run their own group Fortunately, I was able to resuscitate the group. I had some help, since the member who’d walked out supported a move back to the city centre. With the better catchment in this location, we expected to gain visitors as before, and pull back some of our former members. In particular, by locating the group near the Oxford Road student corridor we could practically guarantee one or two new visitors every week. Rather than meeting in a public space, we redoubled our efforts to find a private room. As mentioned, this was difficult without paying. However, the Lass O’Gowrie pub provided us with a semi-private space, in return for which we purchased food and added to their bar takings. If they had no other bookings, they’d even let us use their public performance space, which had a stage area and overhead projector. Other changes were to run the group via consensus decision-making; to abolish the role of group leader; and have a different member taking the lead for each meeting. This sounds unworkable but turned out to be a very good fit. It helps to keep meetings fresh, and spreads out administrative duties. The facilitator also puts together the programme and sends out email reminders. A further advantage is that it empowers group members, some of whom have had little experience with leadership duties. We gained members rapidly, and they attended more frequently. One of them has recently negotiated a meeting room for us at The Manchester College, which has several advantages over the pub setting, not least of which are that we can count on a private space and presentation facilities for every session. For me, it’s a pleasure to take a back seat from the day-to-day running of the group, and to be able to turn up and enjoy meetings in the same way as any other participant. Quotes from members “I’ve been part of various self- help groups up and down the country and the Manchester group suits my needs the most. It has a great variety of people of all ages, ethnic backgrounds, knowledge, skills and abilities. I quickly found myself making friends, whom I’ll keep for the rest of my life. The group continues to enrich my knowledge of stammering (benefitting from several members being involved in current stammering research), challenges my own prejudices and hang-ups, and furthers my journey into self-awareness and acceptance. Quite simply, the people who have attended the Manchester group are some of the most wonderful and inspiring people I have ever met.” Laura Patryas “We cover an interesting range of subjects (e.g., Mindfulness, the telephone, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, etc.). The meetings are always well-structured and balanced. Time is given for the topic of the night and then the second half of the meeting is about speech practice. I find this particularly useful to work on my speech, whether it be reading aloud or doing ‘table topics’ (two minute ad-libbed speeches borrowed from Toastmasters), etc. The social element, with the option of going for a drink after the meeting, is also very important.” Clive Collins The Manchester Stammering Support Group meets every fortnight at St John’s Centre, The Manchester College. Email manchester-stammering@ googlegroups.com for further details. “There are a lot of things I really like about this group, so it’s hard to pick out one thing in particular. I like the fact that there is a solid core of members who, despite still stammering, are doing very well in their lives, and have very definitely gone beyond the common psychological hang-ups that people otherwise often have about stammering. Just being around such people is very therapeutic. I like how the responsibility for co-ordinating meetings is taken by a different group member each time. I like how the group has successfully managed to avoid promoting any particular brand of therapy or self-help, yet at the same time provides members with a lot of useful (and accurate) information.” Paul Brocklehurst Max’s suggestions for starting a group 1. Recruit members from your local NHS Speech and Language Therapy service and ask BSA to list your group on their website; 2. Choose a meeting place near to public transport links. Try to get a private room. Colleges or community groups may help; 3. Have members take it in turns to facilitate meetings. This will reduce the pressure on you, keep the agenda fresh and make members more confident; 4. It may be preferable to resist a formal leadership hierarchy. Try instead to make decisions by consensus; 5. Once the group is running, make yourself dispensable. Contribute as any other member would, and allow the group to come to its own conclusions. That said, you may occasionally need to steer and chivvy things along; 6. Structure meetings so that all participants have an opportunity to talk, if they want to. One way to ensure this is do ‘table topics’, which are a good way to round off the evening. See also the BSA’s guidance and resources on self-help groups, or see if there’s a group in your area, at www. stammering.org/shgs.html. Meetings usually end with a visit to the pub

- 14. 14 SPRING 2014 The British Stammering Association SPEAKING OUT Study on pre-school children draws criticism An Australian study recently published in the journal Pediatrics, entitled ‘Natural history of stuttering up to 4 years of age’, has prompted some in the dysfluency world to question its findings and methodology. We asked one of its authors to provide a summary of the study, and a leading Speech and Language Therapist to respond to it. Professor Sheena Reilly, from the Department of Paediatrics at the University of Melbourne, writes: Recently we reported findings from a study of early stammering1 that surprised many and continues to be the subject of debate. We recruited 1,910 infants, aged 8-10 months, to the Early Language in Victoria Study (ELVS). Within ELVS we embedded a study to examine the onset and development of stammering. This study was different from many others in that: • The children were recruited at a younger age, that is, before many of the children had started stammering; • Information was collected on all participants before they started stammering, as well as at frequent, regular intervals once they started; • Participants were recruited from the community (e.g., maternal and child health centres, magazine advertisements), rather than speech therapy clinics where children were seeking treatment; • In addition to stammering data, information was collected on the children’s social, emotional and behavioural development; • When each child was reported as stammering by their parents, and had it confirmed by one of our speech pathologists, the child was visited at their home on a monthly basis for 12 months. All parents participating in the original ELVS were eligible and invited to participate in the stammering sub-study. The majority of parents elected to participate. Participating families were provided with a fridge magnet displaying examples of different stammering behaviours and prompted every four months to telephone our research team if they noticed that their child had started stammering. Once a parent telephoned to report that their child was stammering, a 45-minute face-to-face assessment was conducted at the child’s home. For those children confirmed as stammering, monthly home visits then took place for one year. In addition to this, a questionnaire was completed by parents every year around the time of their child’s birthday. At 4 years of age, the child’s language skills (comprehension and expression) and non-verbal cognition were measured. Parental reports of the child’s social, emotional and behavioural development and quality of life were also obtained. The main findings were as follows: • Childhood stammering was more than we expected; 11.2% of children were confirmed as stammering by 4 years of age; • Being a twin, being male and having a mother with a higher level of education were all associated with stammering onset. However, this doesn’t mean that these factors together will predict stammering onset. By 4 years of age: • Children who had stammering onset had better language development and non-verbal skills than non-stammering children; • The negative social, emotional and behavioural effects commonly reported to be associated with stammering, were not evident; • Children who stammered were not more shy or withdrawn compared to the non-stammering group; • Children who stammered had better health-related quality of life compared to the non-stammering group. • Only 6.3% of children recovered from stammering in the first 12 months after onset. This recovery rate was lower than had previously been reported. Recovery rates within the first 12 months after onset were higher for boys, for children who did not repeat whole words at onset and for children who had a lower stammering severity at onset. Conclusions We concluded that stammering seemed to be more common in the pre-school years than was previously thought. We were surprised that the negative consequences associated with stammering were not apparent in the majority of children by 4 years of age. Current best practice recommends waiting 12 months before starting treatment unless the child is distressed, parents are concerned, or the child becomes reluctant to communicate. This recommendation is based on research conducted about the Lidcombe Programme, which is the only speech and language therapy treatment for early stammering that is supported by randomised controlled trials2,3 . The evidence indicates that waiting 12 months after onset Prof Sheena Reilly (centre), with Dr Elaina Kefalianos and Peta Newell

- 15. The British Stammering Association SPRING 2014 15 SPEAKING OUT before commencing treatment may actually improve a child’s response to treatment. However, this period involves ‘watchful waiting’, which requires parents to monitor fluctuations in their child’s stammering severity as well as changes to their child’s response to stammering. Given that (a) so few children recovered from stammering in the first year after onset; and (b) there were no detectable negative outcomes by 4 years of age, we suggested that treatment for some children may be delayed for slightly longer than 12 months to allow more time for natural recovery to occur. Limited resources are available to manage early childhood stammering; therefore we argued that these resources should be allocated to those children who do not recover naturally and/or those who experience negative outcomes. Given the low rates of recovery reported in our study, we were unable to determine what predicts which children will recover from stammering, but this will be the focus of our research in the future. References 1. Reilly, S., Onslow, M., Packman, A., Cini, E., Ukoumune, O. C., Bavin, E. L., Prior, M., Eadie, P., Block, S., & Wake, M. (2013). Natural history of stuttering to 4 years of age: A prospective community-based study. Pediatrics, 132(3), 460-467. 2. Jones, M., Onslow, M., Packman, A., Williams, S., Ormond, T., Schwarz, I., & Gebski, V. (2005). Randomised controlled trial of the Lidcombe Programme of early stuttering intervention. British Medical Journal, 331, 659-661. 3. Lewis, C., Packman, A., Onslow, M., Simpson, J.A., Jones, M. (2008). A phase II trial of telehealth delivery of the Lidcombe Program of Early Stuttering Intervention. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology, 17, 139-149. Response by Elaine Kelman, Head Speech and Language Therapist at The Michael Palin Centre: This ongoing study of 1,910 children in Melbourne, Australia, caused a significant stir when the investigators published their paper last year, reporting their findings on 142 children who stammer up to the age of 4 years. The popular press responded in typical fashion, selecting snippets of information from which they created dramatic and misleading headlines, such as ‘Pre- schoolers’ Stuttering Not Harmful’ (USA Today) and ‘Children who stutter do not suffer disadvantage at school’ (Daily Mail). This was extremely unfortunate, given that the study’s most significant finding, namely that many more children experience stammering and fewer of those stop within a year than was previously thought, became somewhat buried. There followed a flurry of exchanges, beginning with the Stuttering Foundation of America’s ‘A Blunder from Down Under’ electronic correspondence between the authors and commentators Joseph Donaher and Ellen Kelly in Pediatrics (read at http://bit.ly/1j7D9in); the Michael Palin Centre’s ‘Good news? Bad news? There is such a thing as bad publicity’ (http://bit. ly/1gezaOS); verbal presentations on the Stutter Talk podcast (www.stuttertalk. com/tag/sheena-reilly/); and most recently an article by Ehud Yairi in the Stuttering Foundation’s winter newsletter (http://bit. ly/1gCLzqc). In this article, I will attempt to outline the key areas of debate that have arisen. The primary concern among professionals arose from the potential unintended consequence of the above media headlines, that “parents may be discouraged from seeking advice, doctors will assure them that the child will be fine and the opportunity for early intervention will be lost” (Kelman). There was also concern that the findings indicated that children in this sample “showed little evidence of harm to their mental health, temperament, or psychosocial health- related quality of life”. Donaher and Kelly questioned the authors’ interpretation of this data and pointed out the importance of clinicians continuing to evaluate and address the psychological wellbeing and emotional reactions of a child who stammers. There is no question that stammering can have an impact on these areas from an early age in some children and this is often the reason why parents seek therapy for their child. One of the limitations of large group studies is that the results of a minority can be lost in the process of exploring the group average. Methodology It is also important to note that the population reported on by Reilly and colleagues is not a clinical population. It represents a population of all children who start to stammer, rather than those who stammer severely or are concerned enough to seek therapy. So for therapists, it is important to understand that the results and recommendations of this study do not necessarily transfer to the child in the clinic and therefore Donaher and Kelly are right to state that the impact of the stammer should continue to be considered. Yairi celebrated the excellent use of a “good- size” longitudinal sample, representing the general population of an area, starting in very early childhood and employing multiple variables. He expressed concerns about previous studies that were not referred to, pointing out that the findings regarding incidence, the children’s superior language skills and their temperament characteristics had been reported in articles dating back to 1957. In response, the authors stated that this was due to insufficient space and the different nature of this study. The 12 months recommendation There have also been concerns about the authors’ suggested guidelines for intervention. Firstly, relating to the recommendation to delay treatment for 12 months unless the child is distressed, there is parental concern, or if the child becomes reluctant to communicate. Some of those responding to the article and ensuing publicity were worried that parents and other professionals will focus on the ‘wait and see’ aspect of this recommendation, rather than the proviso, to be watchful and commence intervention if there are certain indicators. The second concern was the recommendation that when therapy is indicated it should be the Lidcombe Programme, which is not the only evidence-based approach and is not the only option. In the discussion that followed, the authors emphasised their original point that these recommendations arose from the original research into the Lidcombe Programme, not from this epidemiological study. This is a longitudinal study which will help us to understand more about the development of stammering over time; the factors that contribute to the disorder; and the impact that it has for different age groups. It is exciting that this new research stimulates debate which subsequently encourages accountability and open-mindedness and above all moves us forward as we seek to understand, support and ultimately help to improve the lives of children who stammer. Elaine Kelman