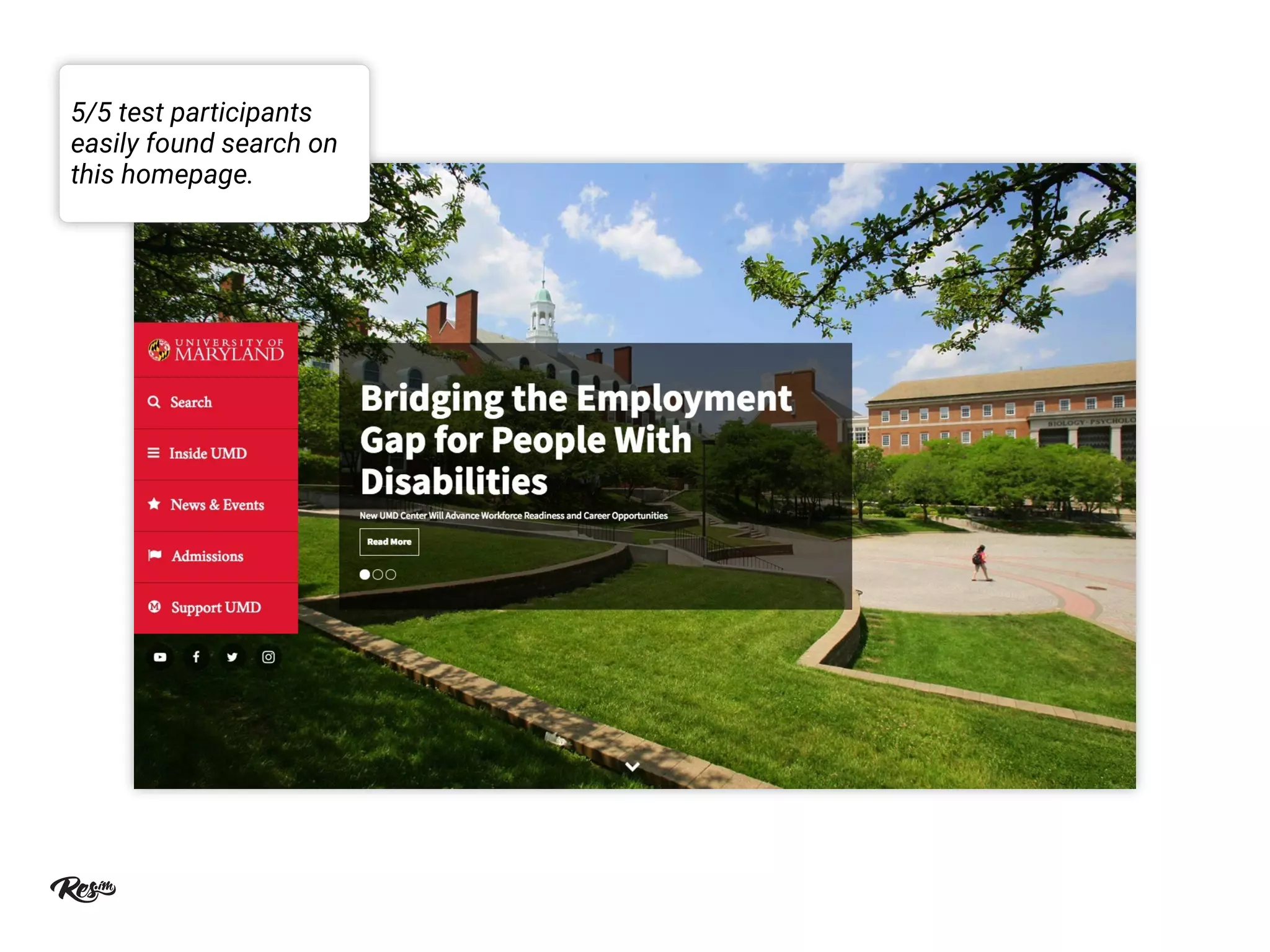

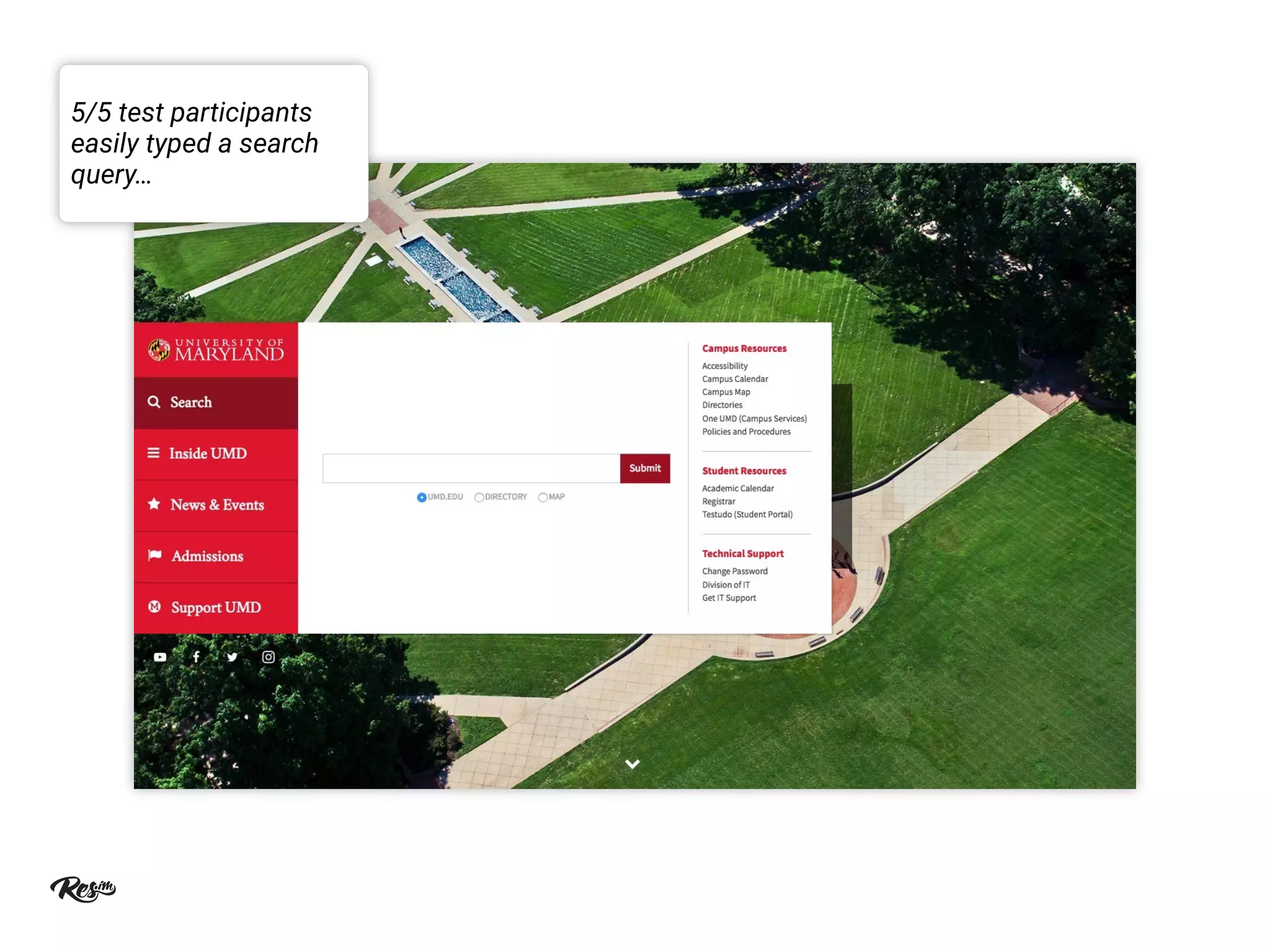

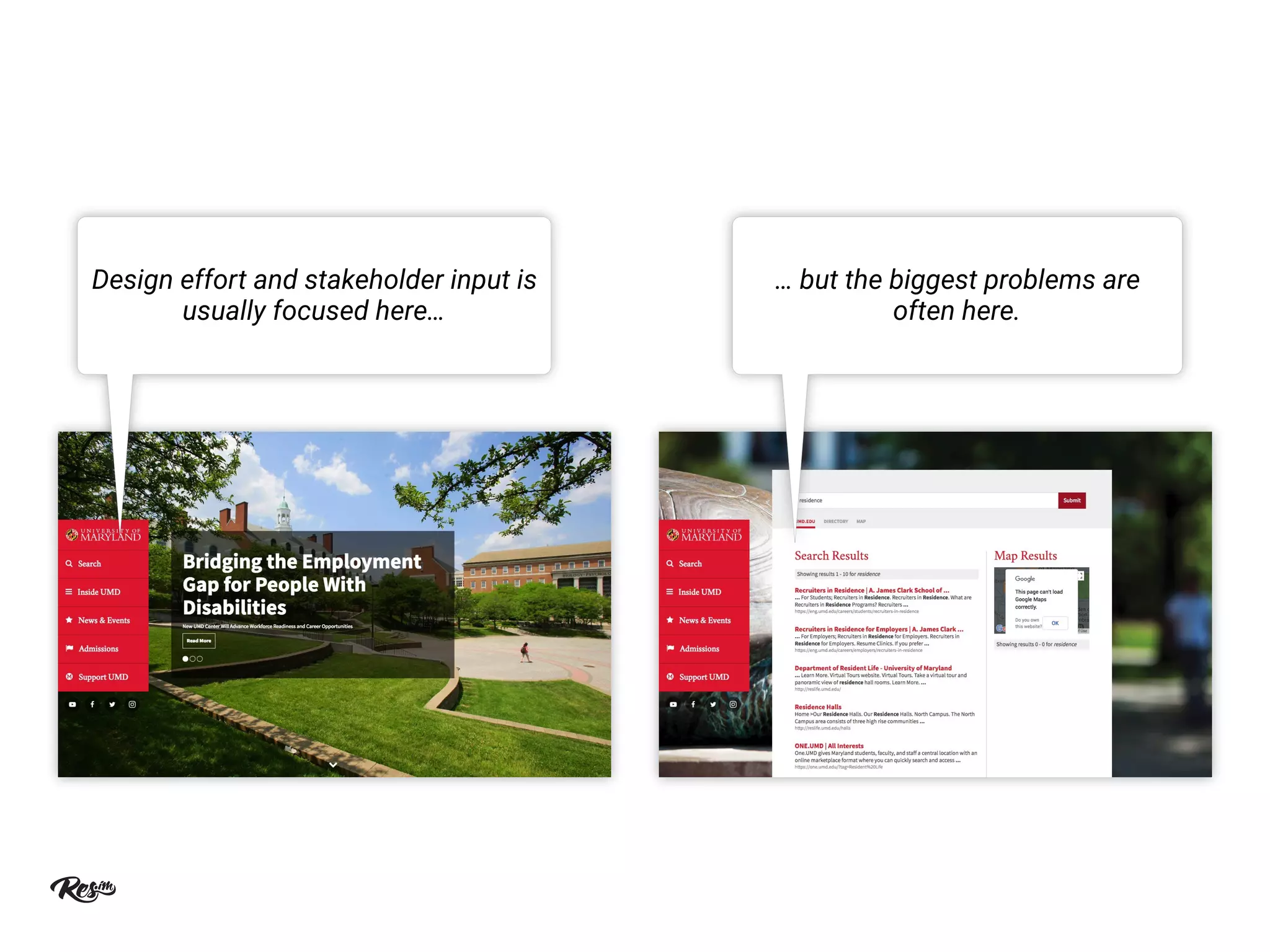

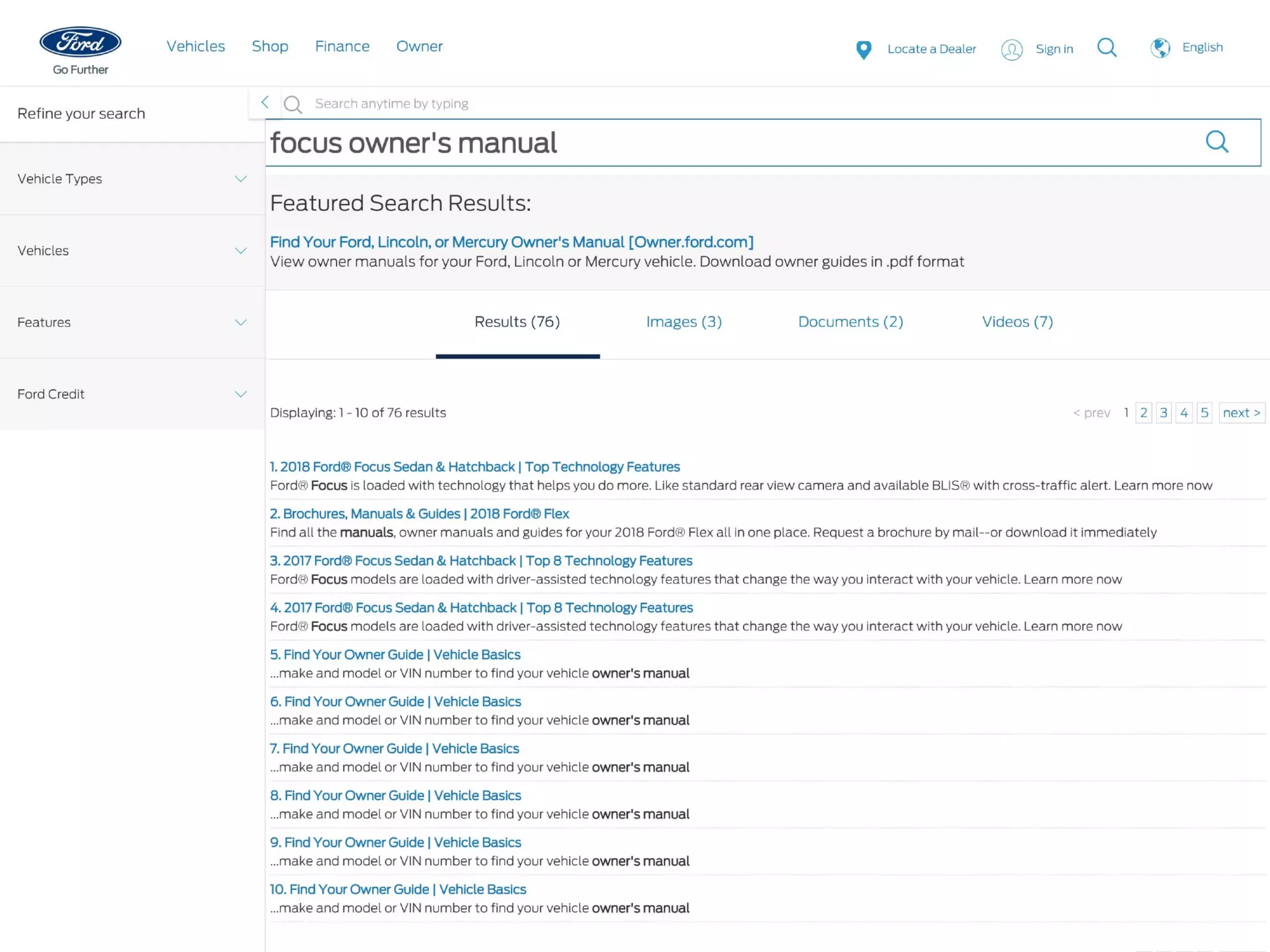

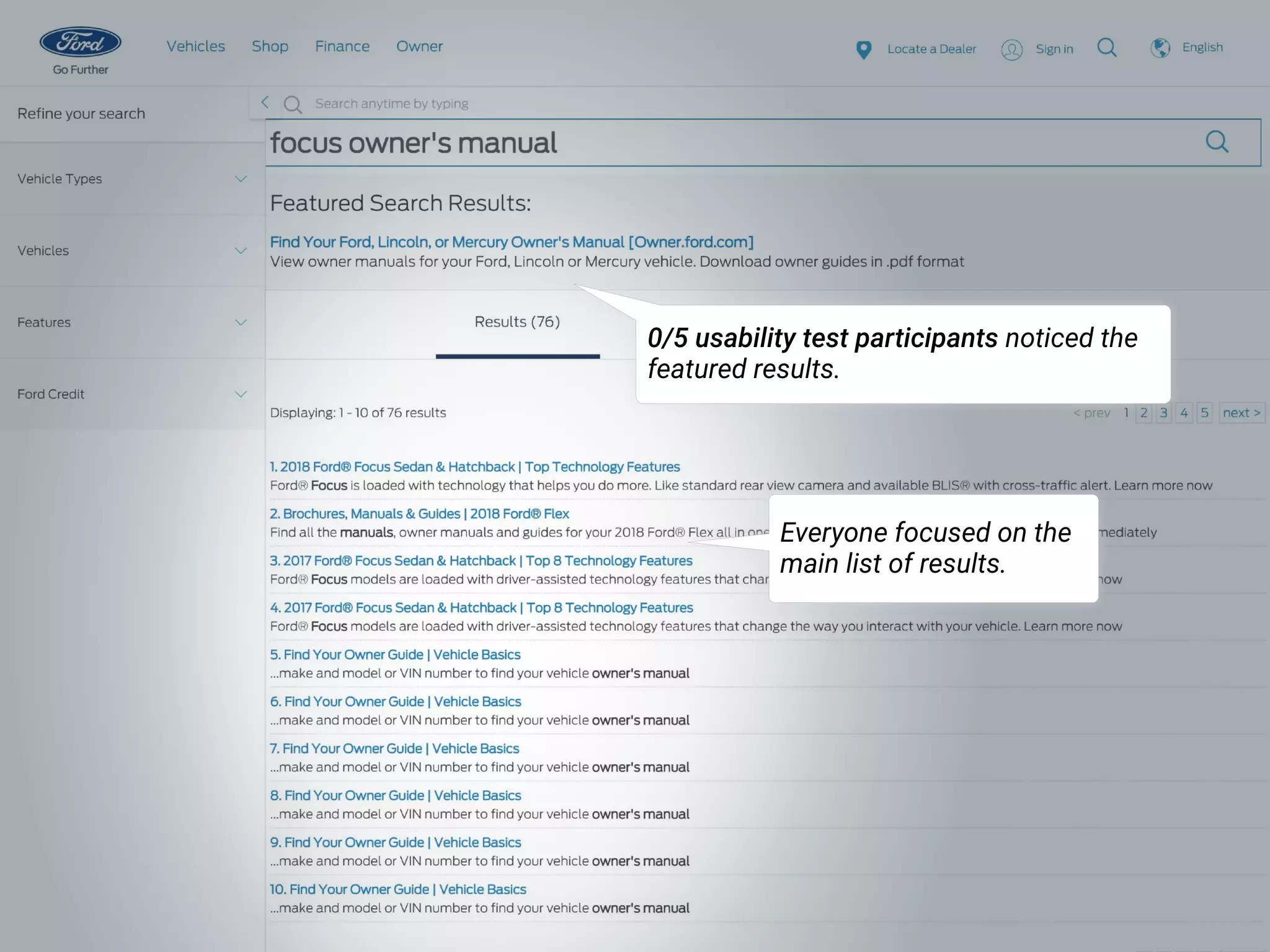

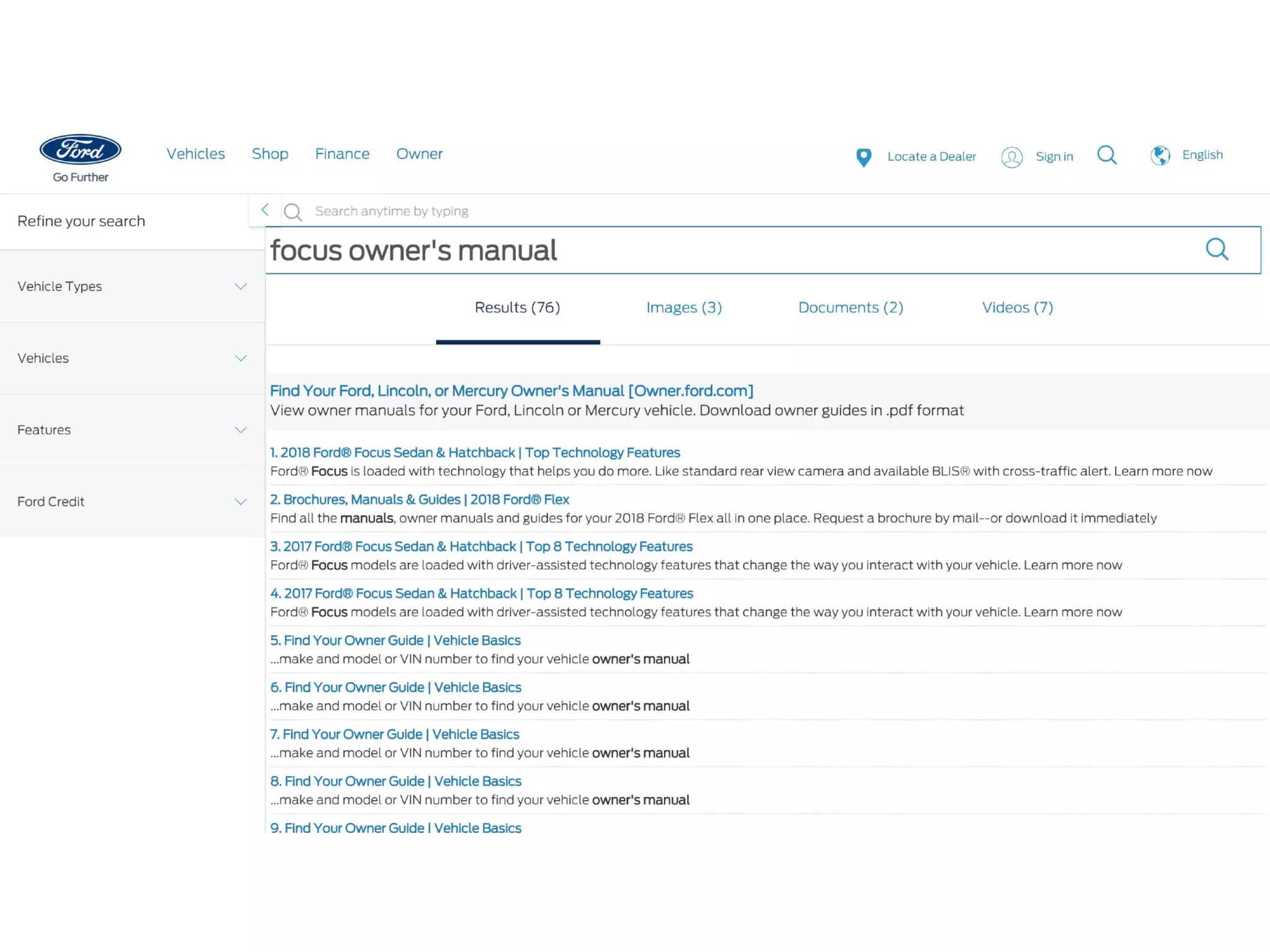

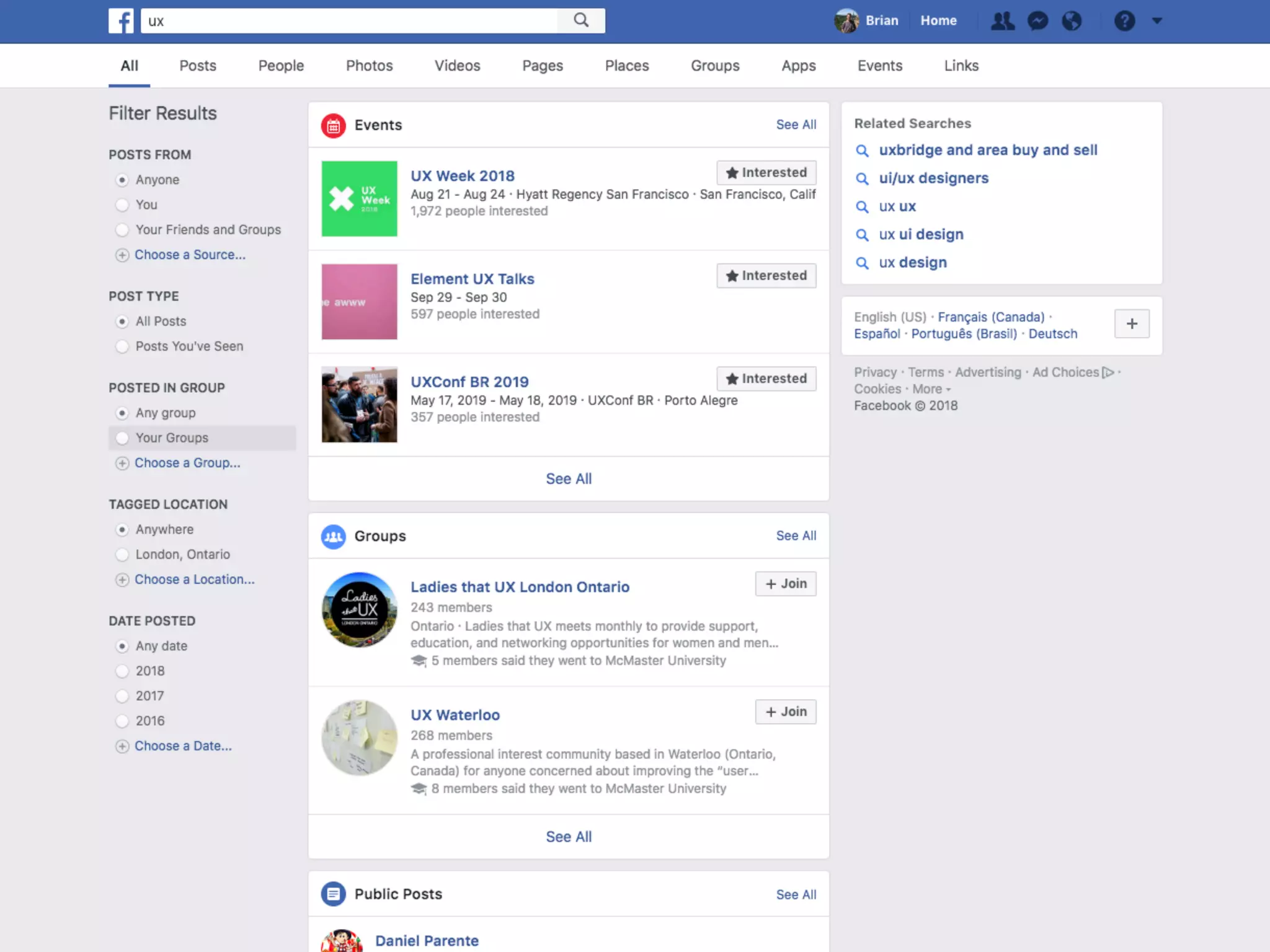

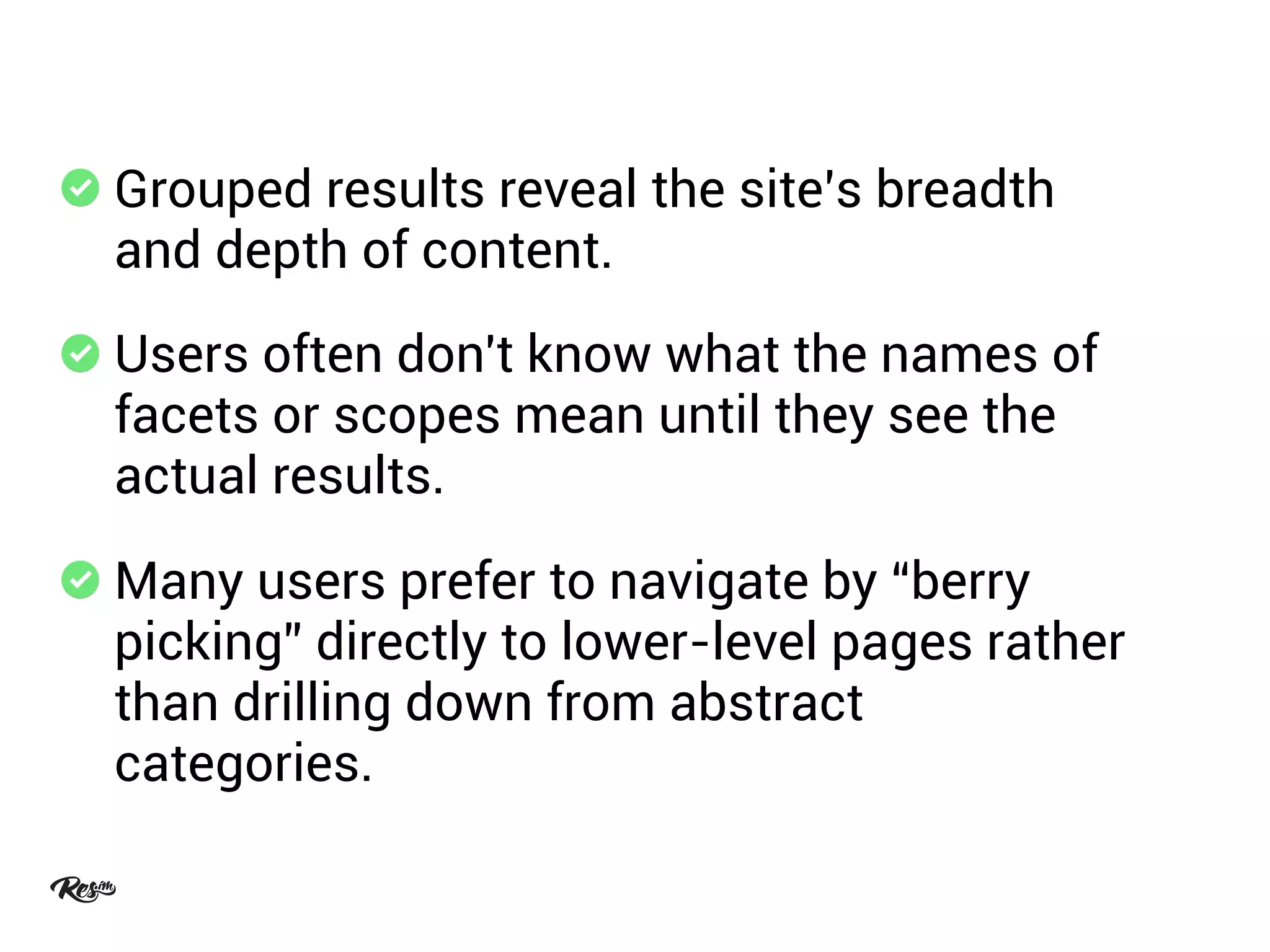

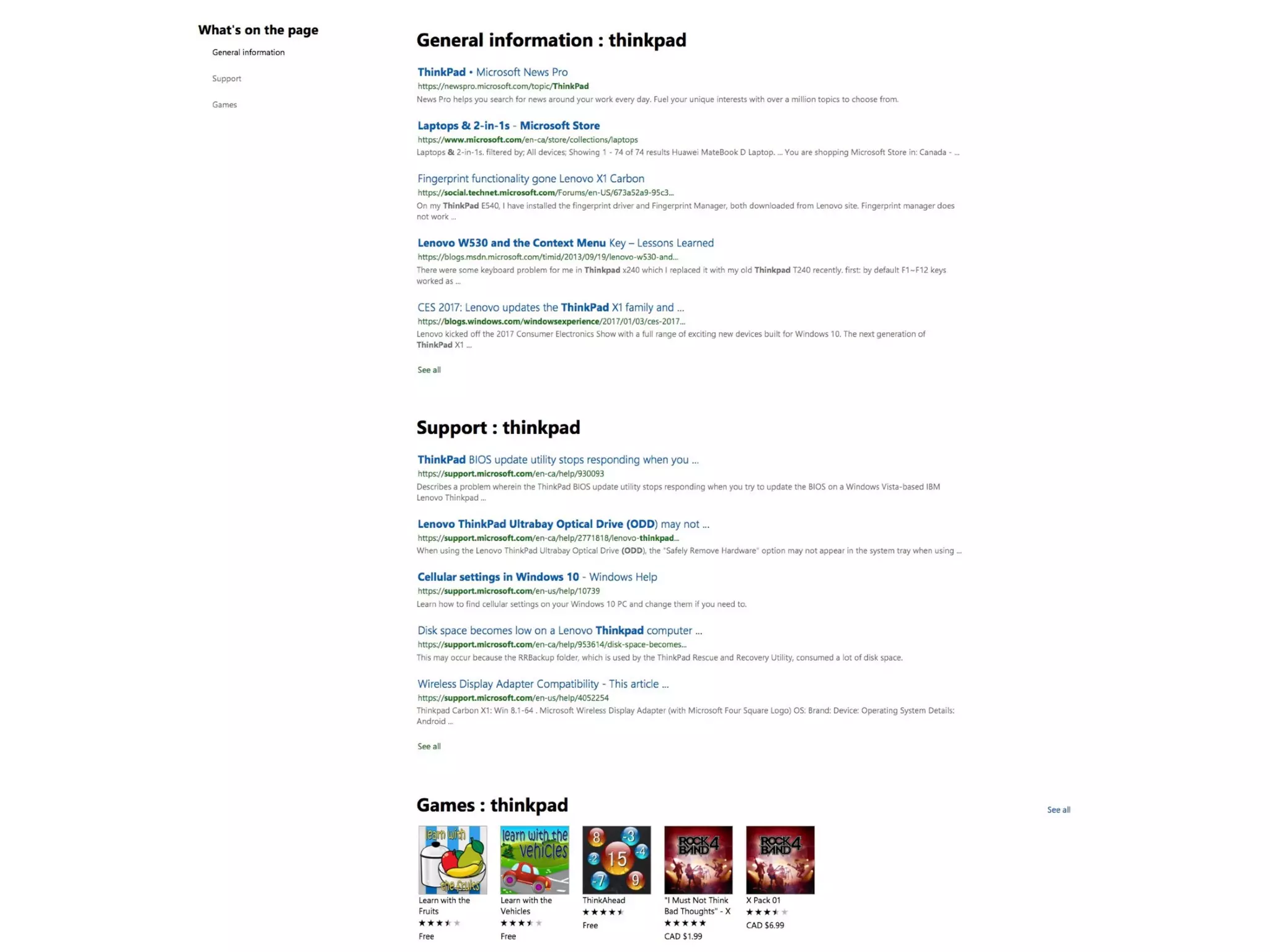

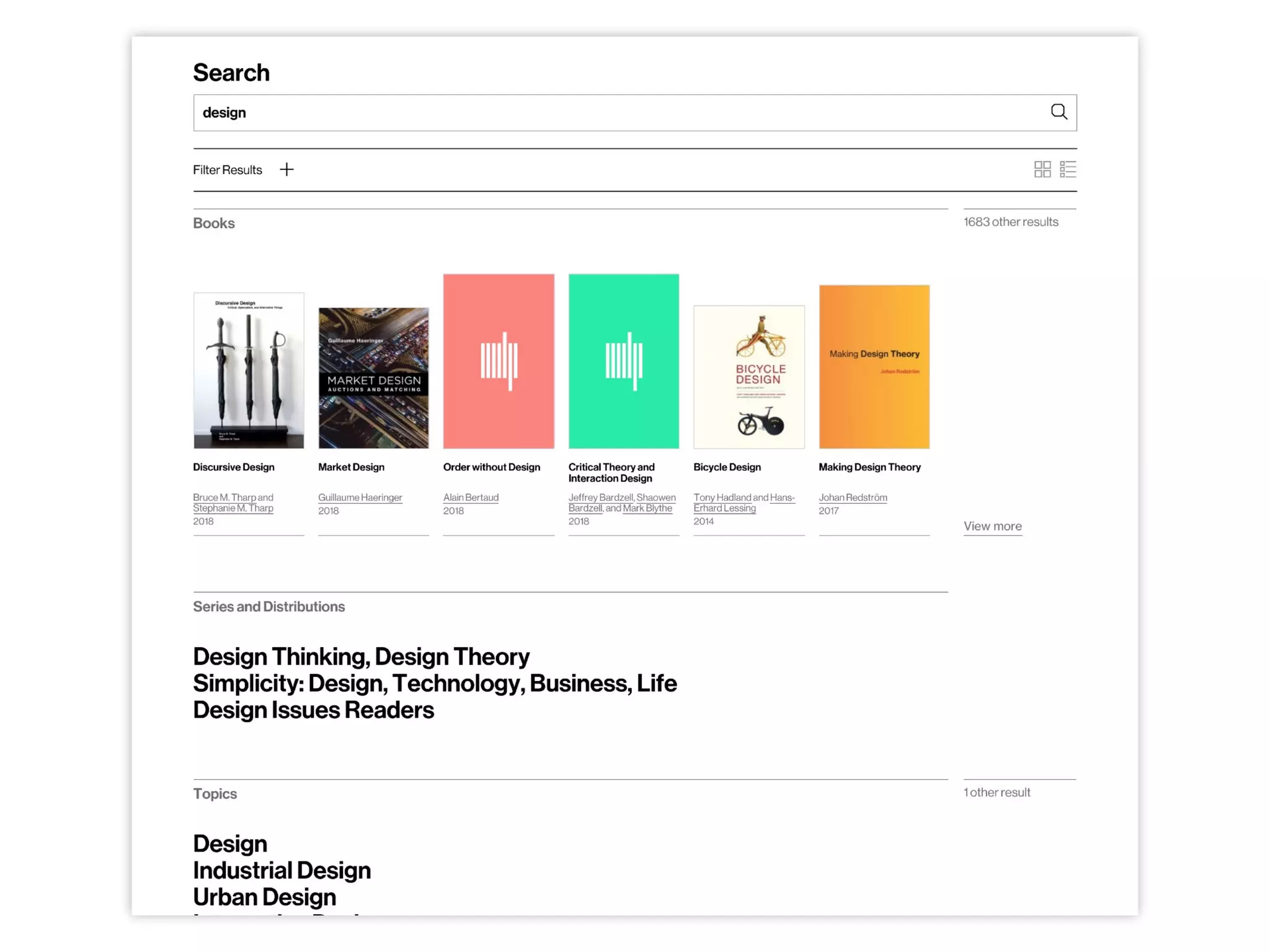

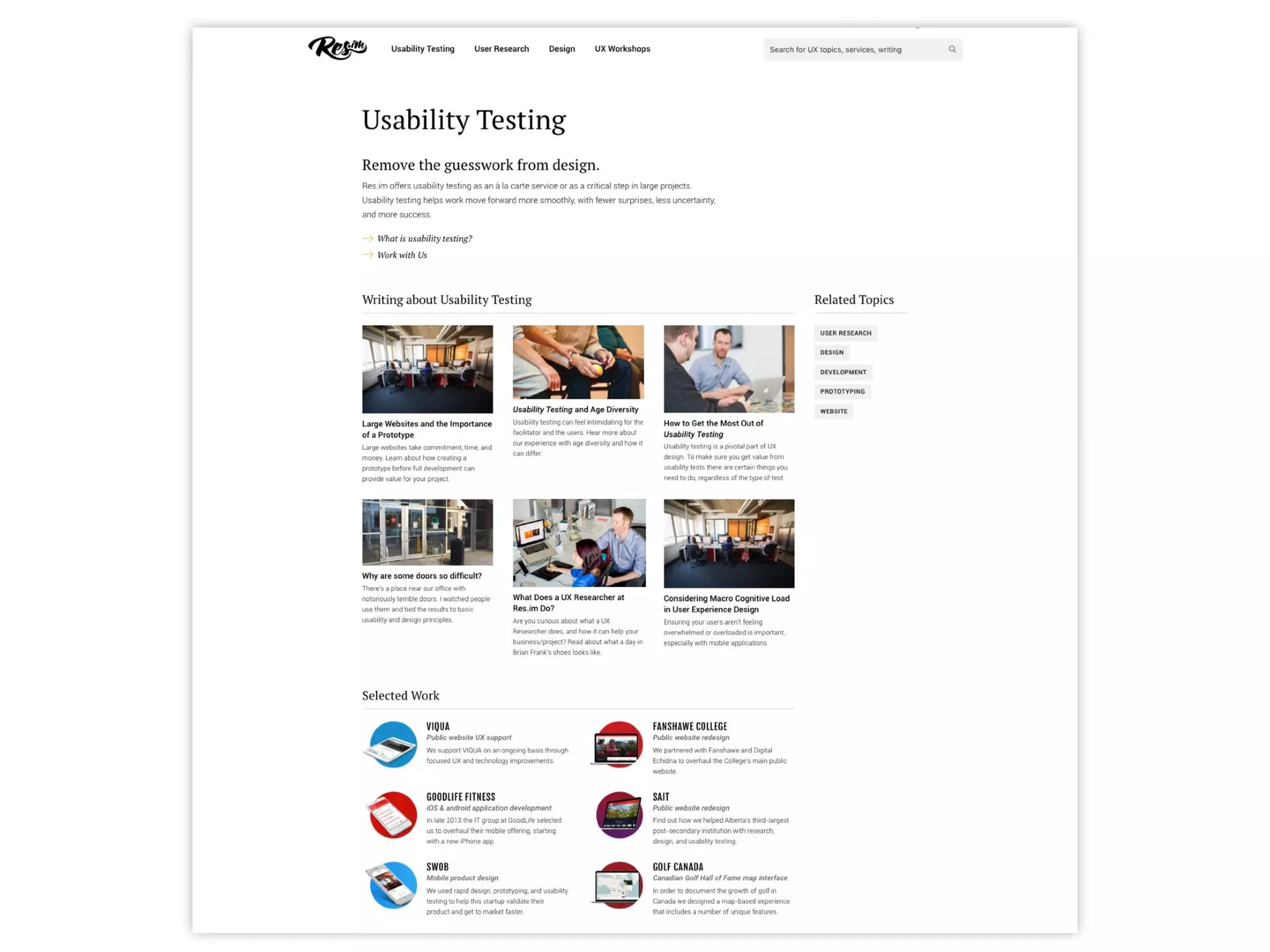

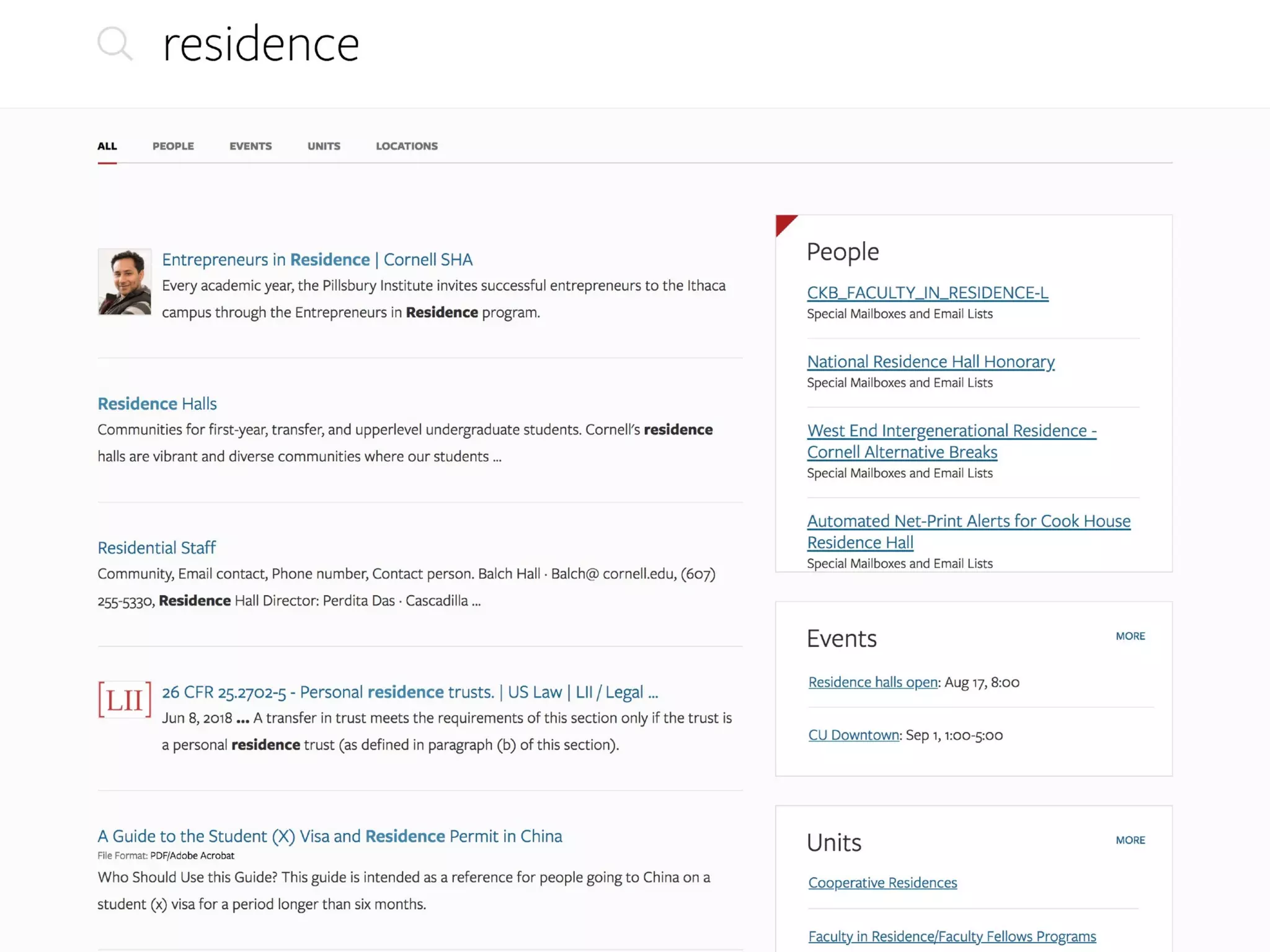

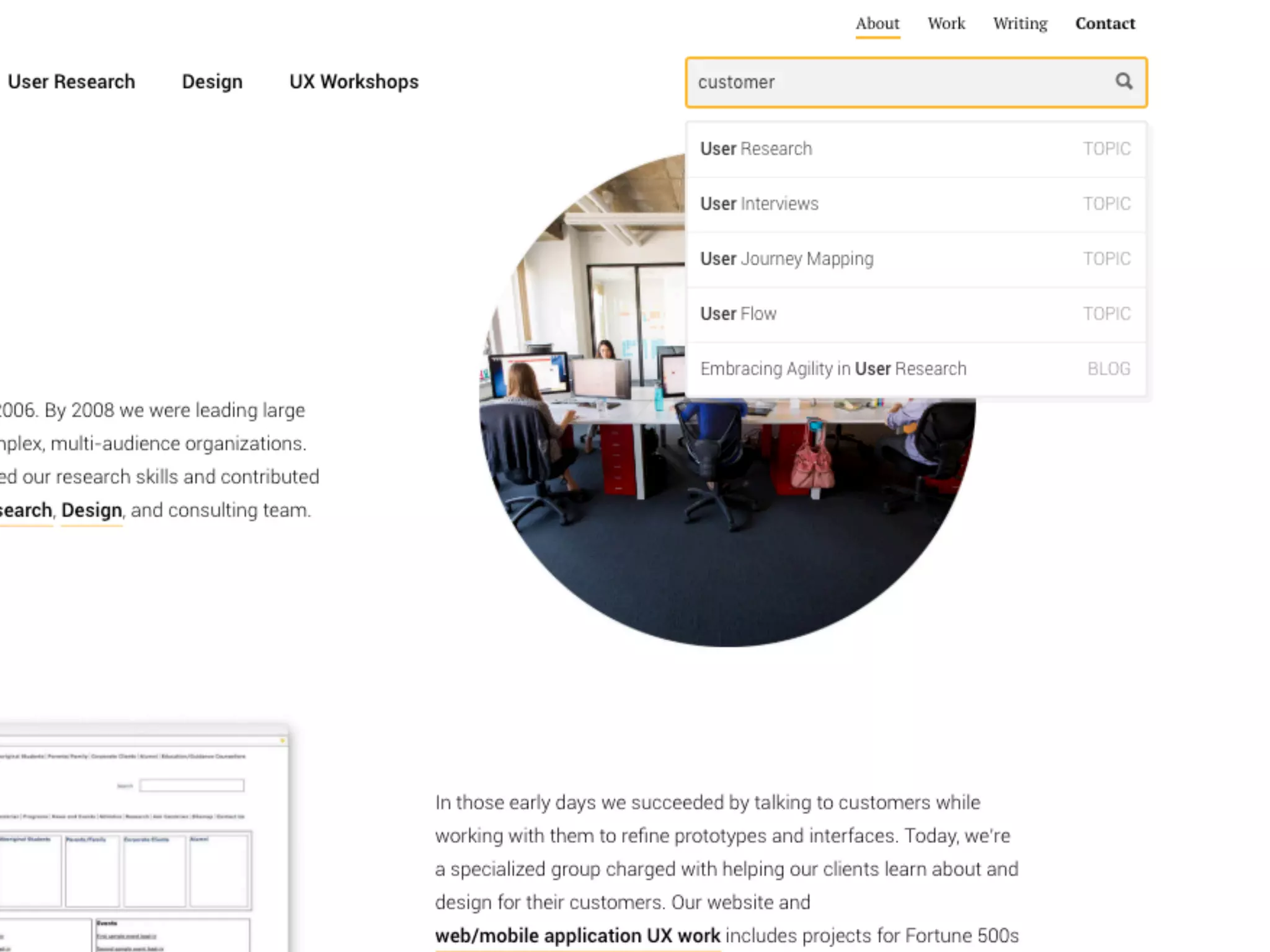

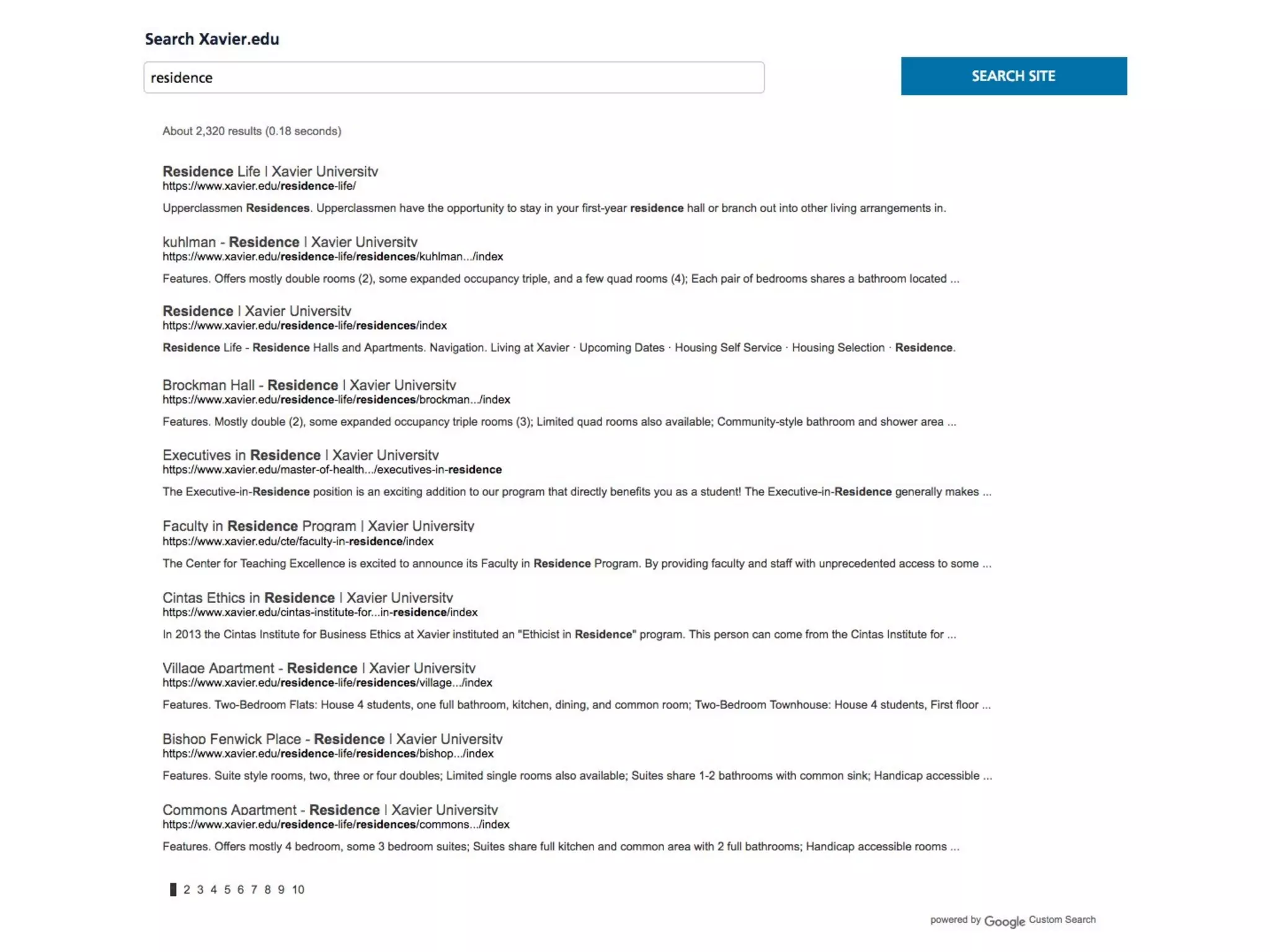

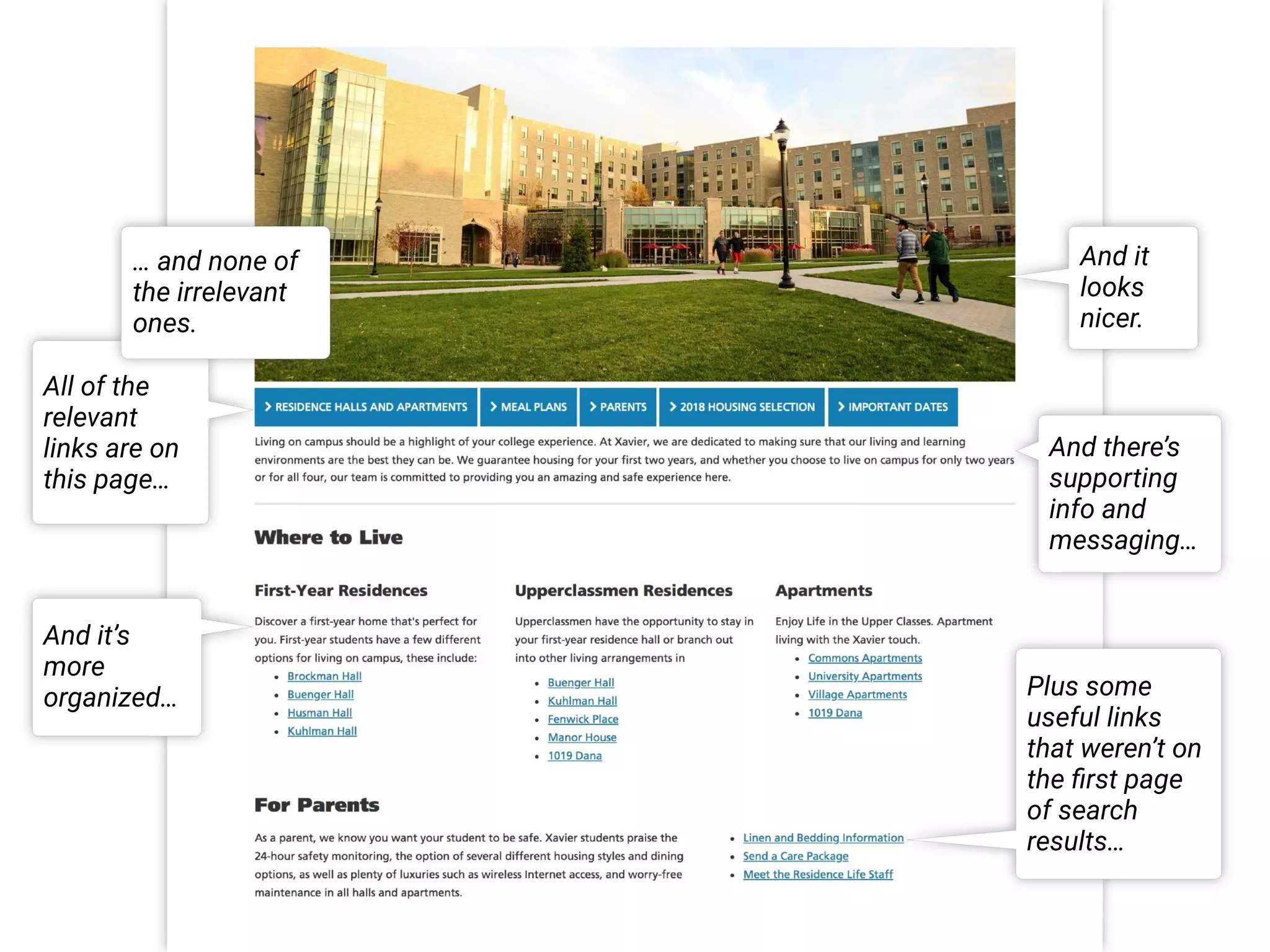

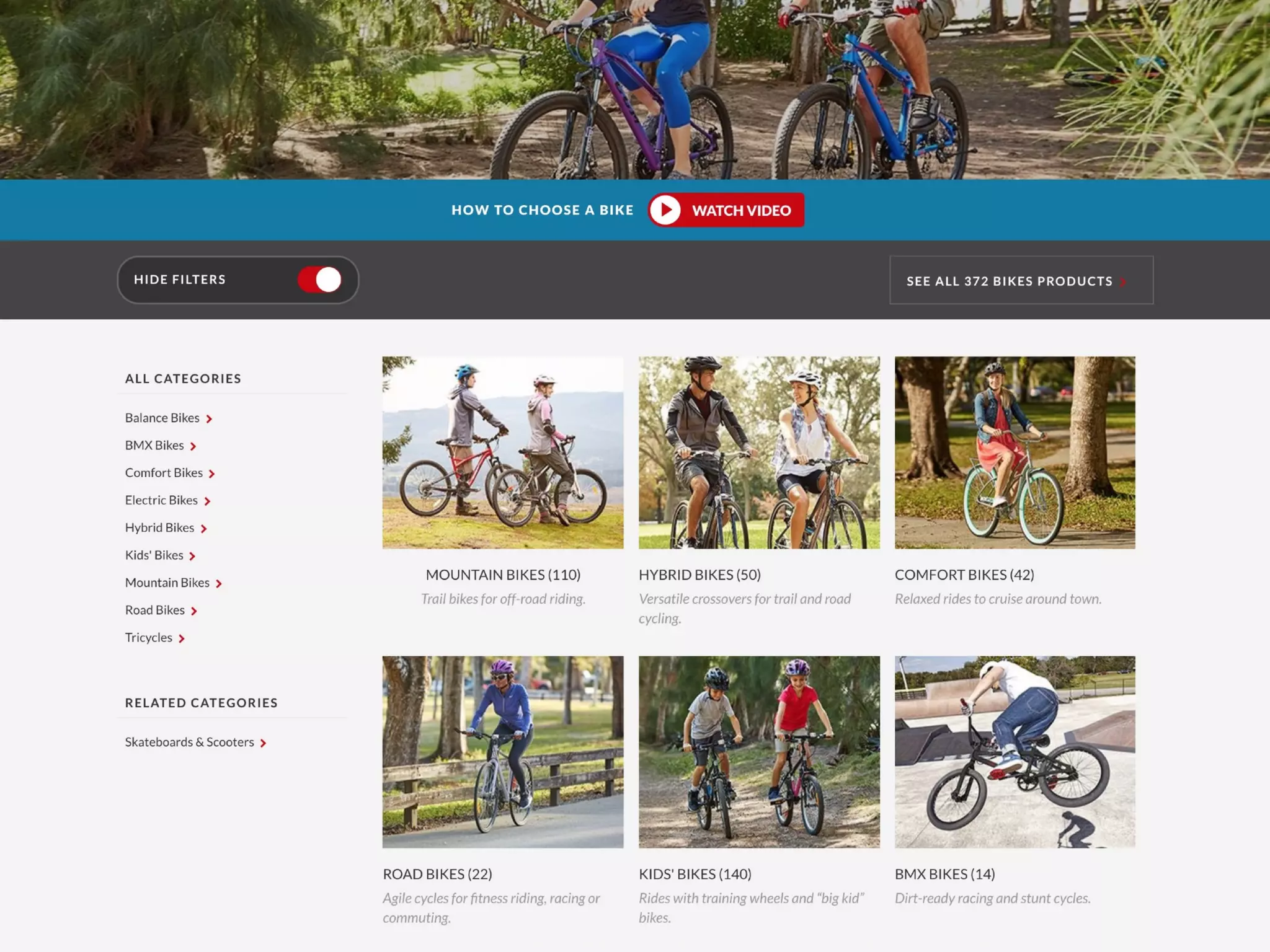

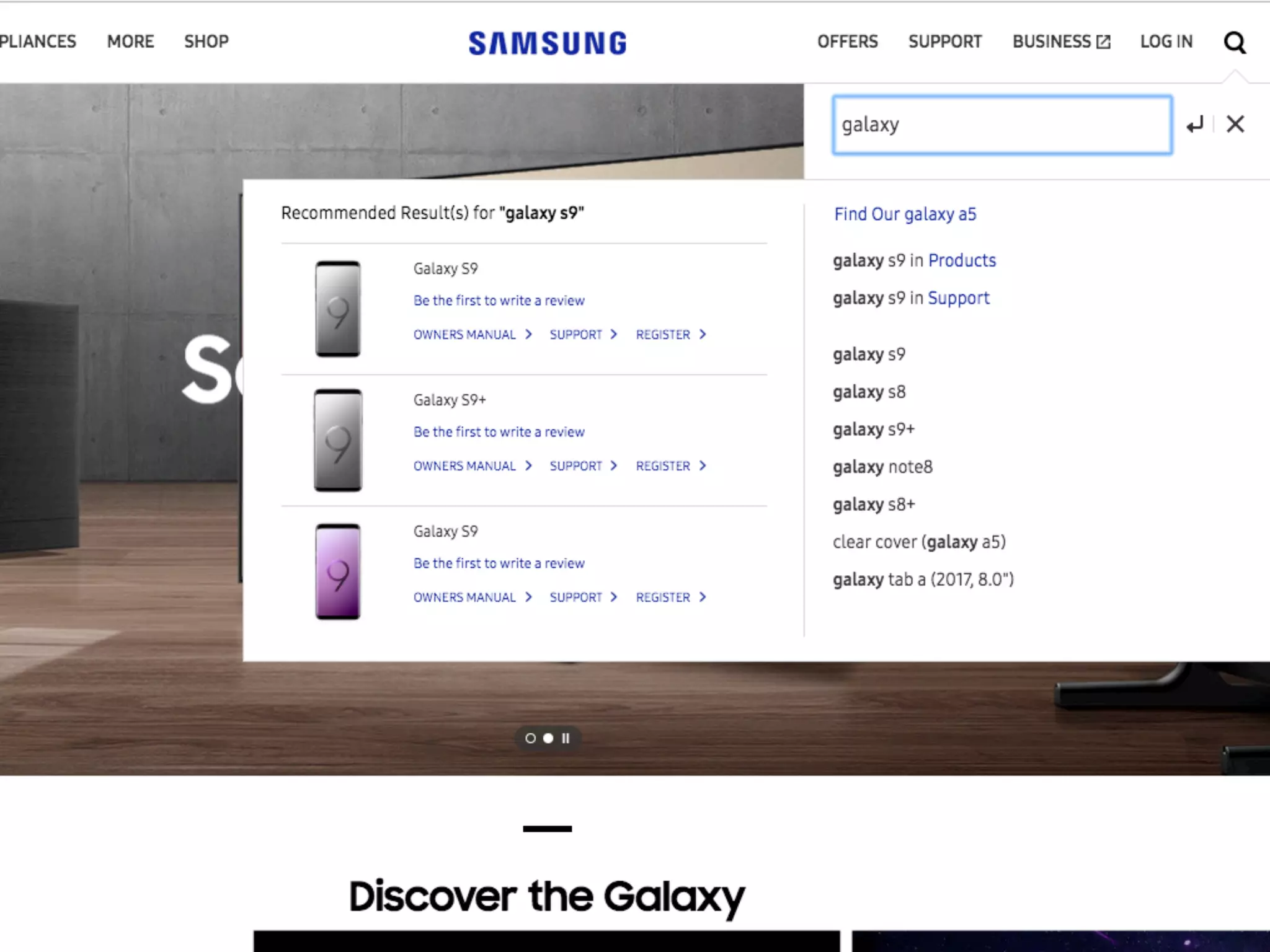

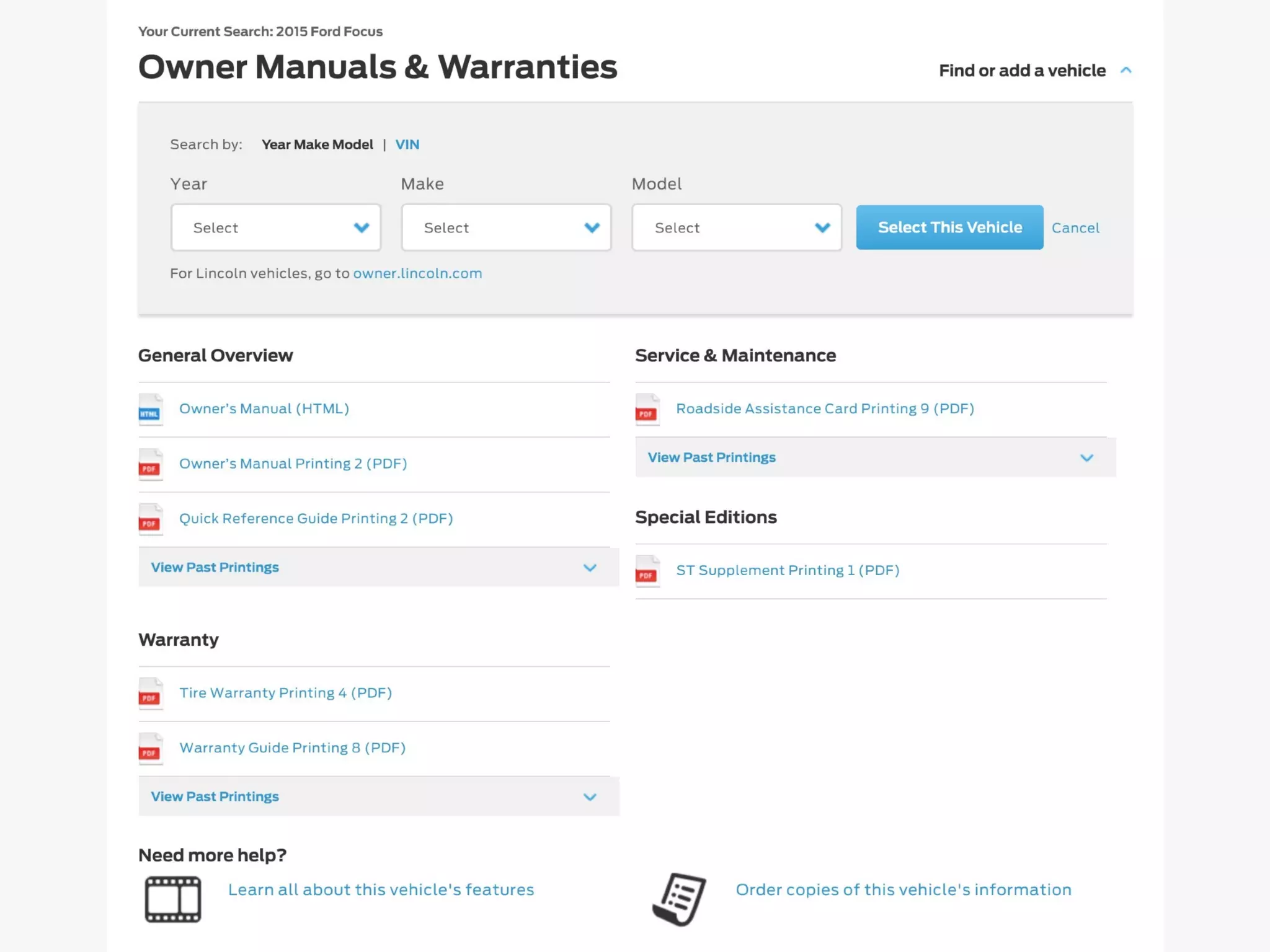

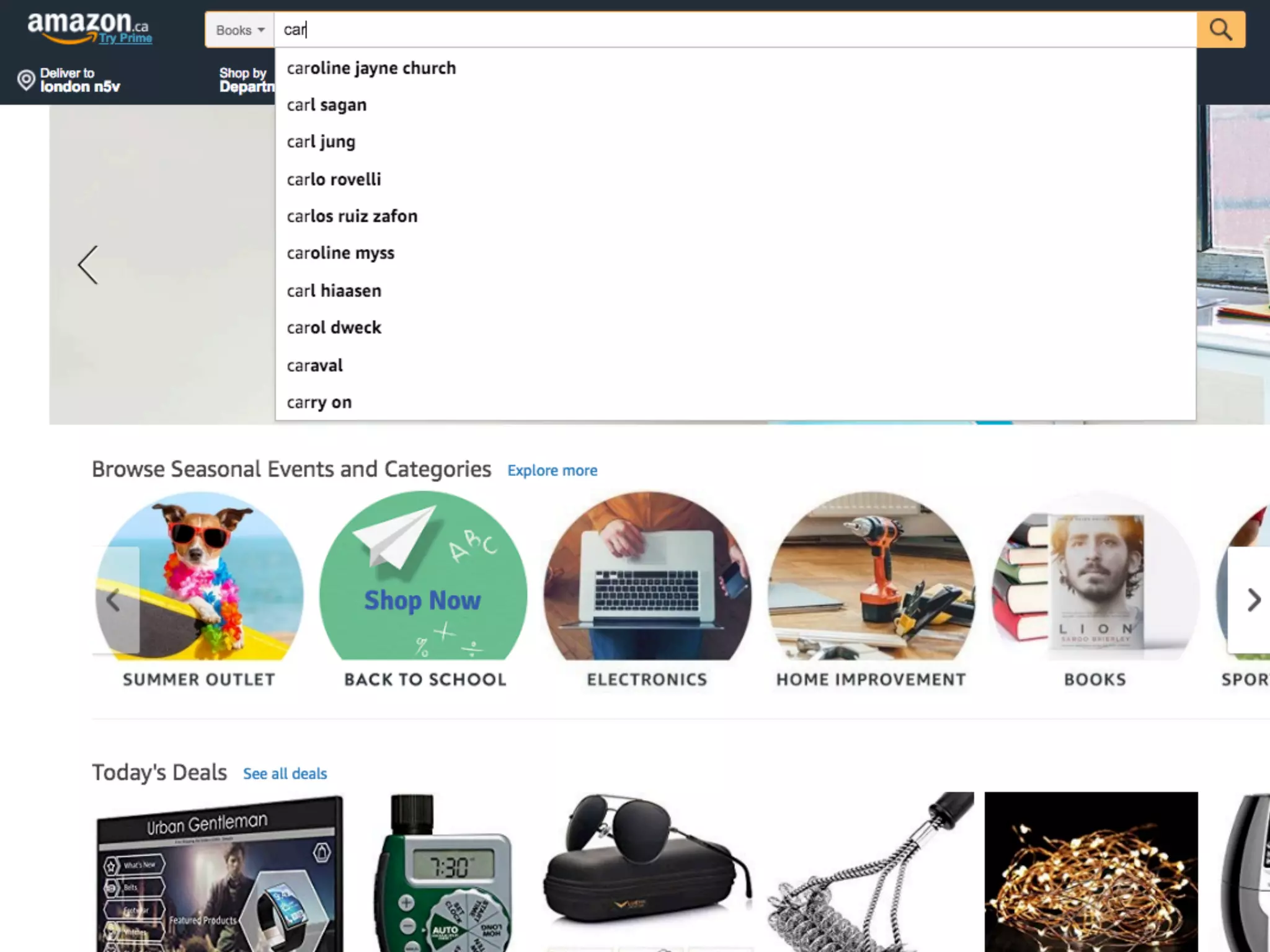

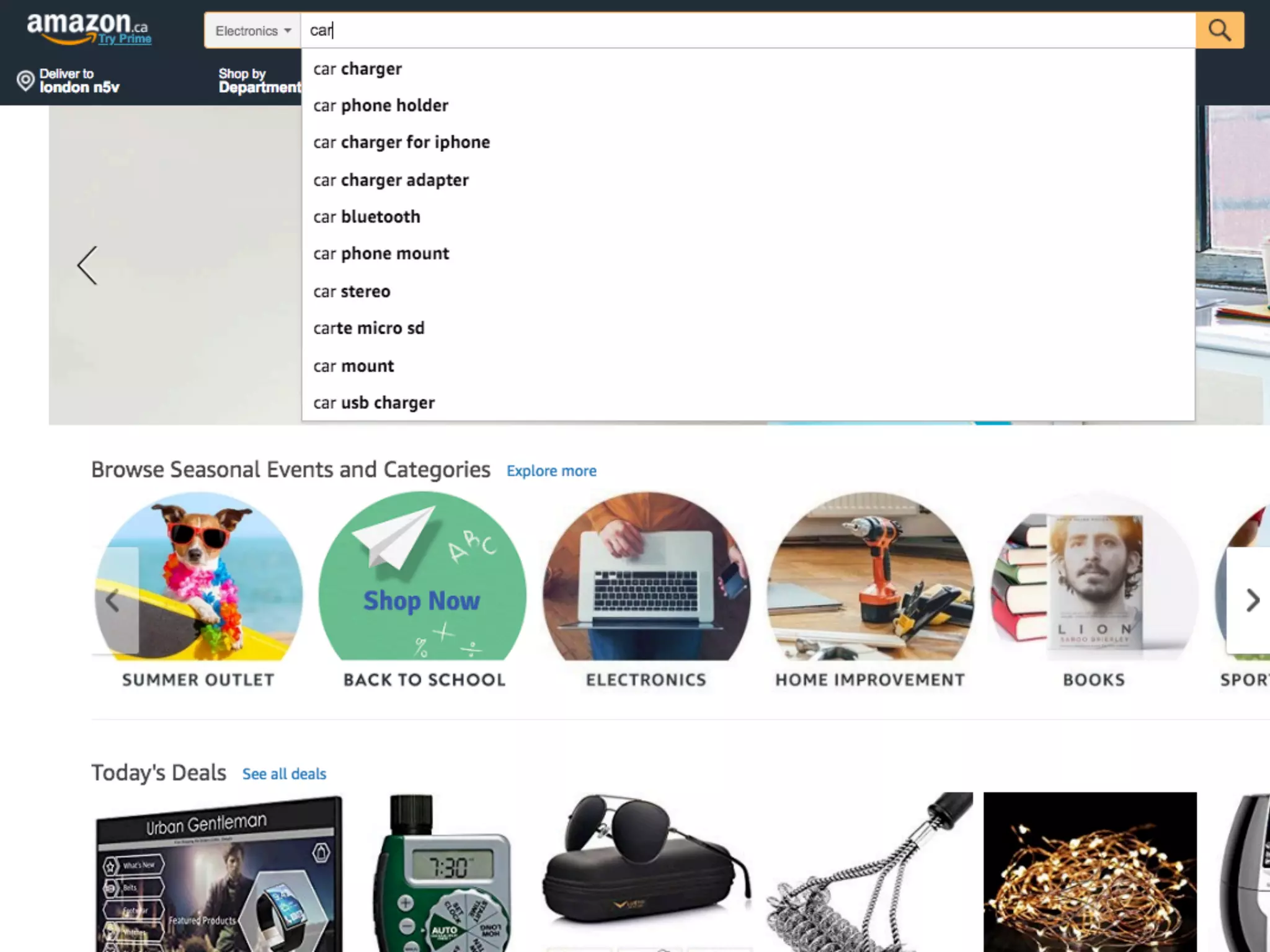

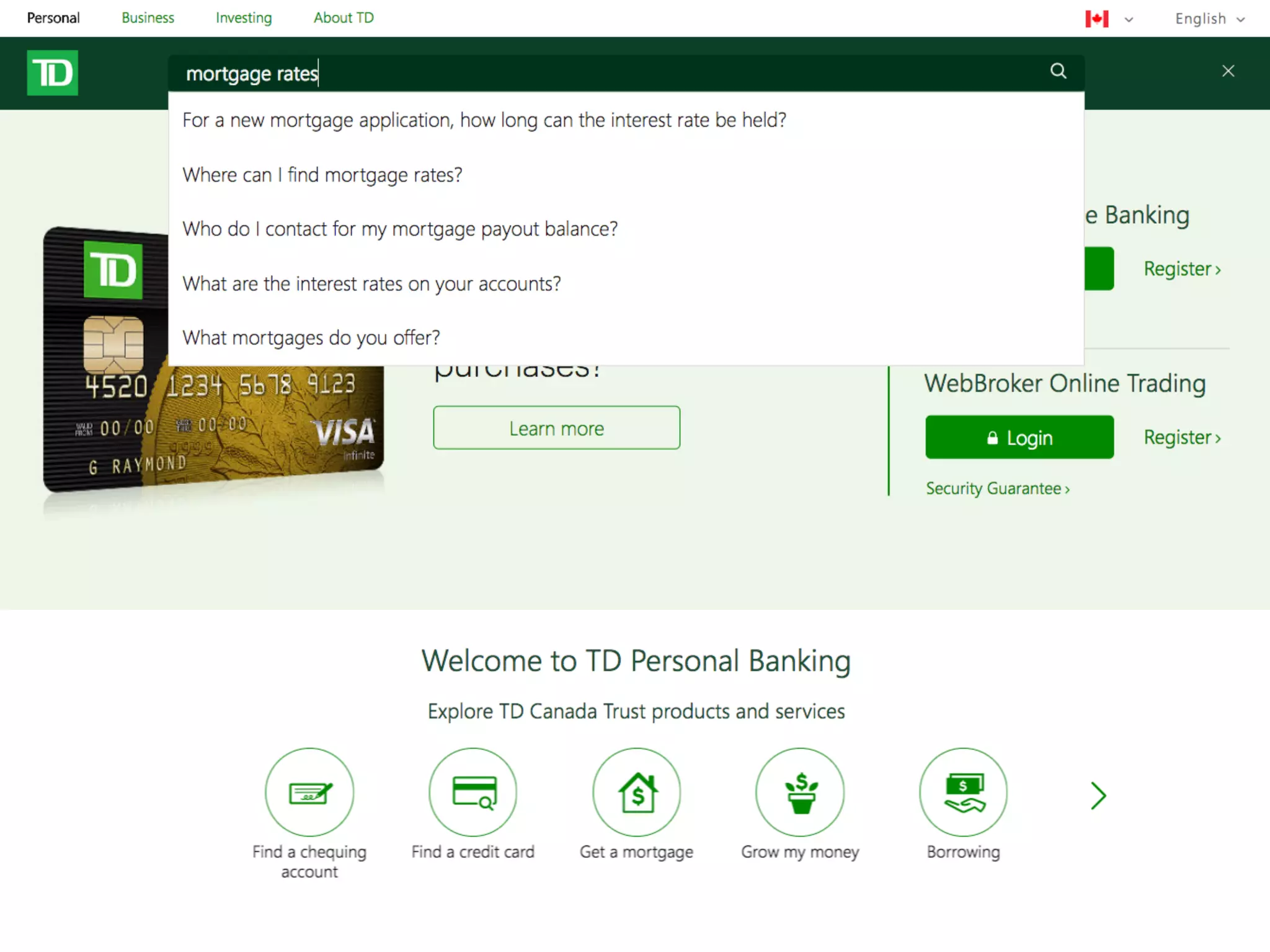

The document summarizes strategies for improving university and college website search functions from a user-centered perspective. It recommends a three-phase approach: 1) Understand users through analytics, user flows and interviews; 2) Clean up content and leverage existing search features; 3) Test improvements like featured results, grouped results, redirects, autosuggestions and scoped/contextual search. The document cautions against "technology-first" approaches and advocates testing changes with users to address small usability issues that make a big difference in search experiences.