This document is a thesis submitted to Mount Holyoke College examining factors that influence the outcome of U.S. mergers and acquisitions bids between 2009-2013. The author aims to take a holistic approach, analyzing how characteristics of the target and acquiring firms, deal specifics, and macroeconomic indicators relate to whether a bid is accepted and the final bid value. Prior research has largely focused on acquirers' perspectives, but the author argues targets' willingness to sell is also important. A literature review is followed by descriptions of the data and variables collected, preliminary statistics, and the logistic regression and linear regression models used to predict bid outcome and value. Key findings are that persistent negotiation, increasing GDP coupled with volatility raise bid success

![each bid. Previous research pays close attention to bid premium at different

time before the announcement date and typically include 3 of these time tags:

90 days, 60 days, 30 days, and 1 day before the announcement date. It is

argued that rumors about mergers and acquisitions start several weeks before

the announcement date, therefore I included in my data set stock quotes at 90

days, 30 days, and 1 day before the announcement date. Historical stock

quotes are readily accessible for almost all firms in my dataset on Google

Finance and InvestorPoint. Historical stock quotes for target firms that stop

trading after merger and acquisitions are available in Bloomberg. Walkling

(1985) draws attention to the base date used in premium calculating. He

argues that taking the date following SEC filings would lead to an

underestimated bid offer premium, since news about takeover, merger and

acquisition appears first in the financial press or press release from involved

firms (before the full-fledged report with SEC), and sometimes circulated on

the street months before the official announcement. The base price () for

premium calculations is the closed priced at t equals 1 day, 30 days, and 90

days before the date the transaction is made public via financial news.Bid

premium is calculated as:

Bid premium at time t = [(Bid Value - Stock Price at time t)/ Stock price at time t] * 100

The inconsistence in findings on the effect of bid premium on bid outcome

can be explained in several ways, for instance, deal rumors spread on the

'34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd1d54aa-e2a4-48fb-9ff6-755ecfc69e0e-161002205956/85/Phi-M-A-Thesis-44-320.jpg)

![streets months before the official announcement date, the variability in stock

prices follows a random walk, and stock prices reflect market’s expectation of

a company’s worth, not the true worth itself. I propose using bid appreciation

in place of bid premium as a determinant of bid outcome. Bid premium and

bid appreciation contain drastically different information about the bid. Bid

premium measures the surplus between the acquirer’s bid and the target’s

stock value at a given time, whereas bid appreciation measures the jump to

acquirer’s final bid from its initial bid. Bid appreciation is calculated as

followed:

Bid appreciation = [(Final bid - Initial Bid)/Initial Bid]*100

Since the base value is now the initial bid (instead of the presumably

“unaffected” stock price), bid appreciation reflects information true to the

value assigned to target by acquirer while controlling for the shifting in stock

prices and other events affecting the stock price before announcement date.

As stated above, macroeconomics data of interest include VIX

(volatility index), Fed’s fund rate and GDP (gross domestic product).

Econstats.com and the Federal Reserve Systems provide daily data on VIX

index and Fed fund’s rate respectively from which I calculated the weighted

average quarter and annual. The US Bureau of Economic Analysis provides

GDP data (available as both quarter and annual value and in 2009 dollars in

this dataset) that can be merged with the bid’s data by time tag.

'35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd1d54aa-e2a4-48fb-9ff6-755ecfc69e0e-161002205956/85/Phi-M-A-Thesis-45-320.jpg)

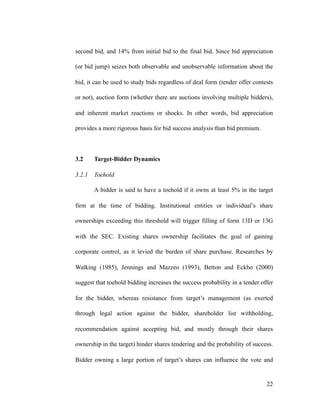

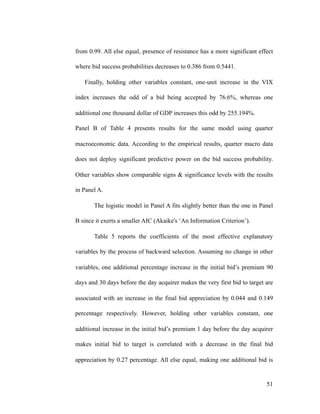

![APPENDIX

List of Industry by SIC Codes

Codes Used in R:

#Data clean-up & Descriptive Stats

mydata = read.csv("WIP.csv", header=T)

attach(mydata)

mydata$accepted = as.numeric(Rejected == 0)

rej = mydata[mydata$Rejected == 1,]

acc = mydata[mydata$Rejected == 0,]

mydata$SizeRatio=ASales/TSales

Industry First 2 digits of SIC code

Mining & Petroleum 10 to 13

Construction & Transportation 17, 40 to 47

Consumer Products (Food, Textile,

Print)

20, 22, 23, 26,27

Chemicals 28 to 34

Manufacturing 35 to 39

Communications 48

Wholesale of utilities, services &

products

49 to 51

Retail 52 to 59

Healthcare 63, 64, 80

Services 67, 70 to 87

'64](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd1d54aa-e2a4-48fb-9ff6-755ecfc69e0e-161002205956/85/Phi-M-A-Thesis-74-320.jpg)

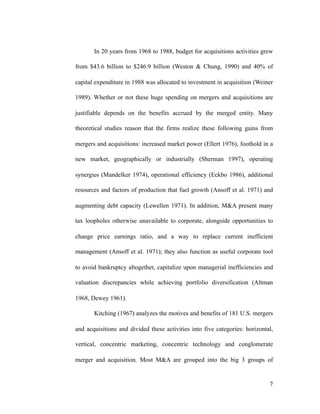

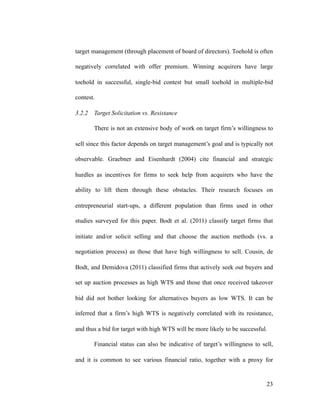

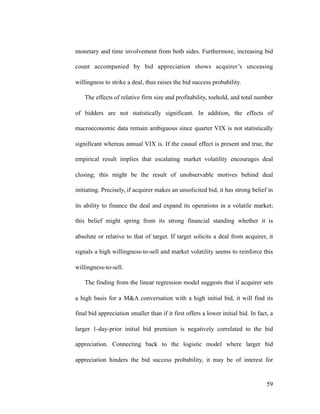

![Codes Used in R: (Continued)

dim(mydata)

attach(mydata)

#Backward selection of model

full=glm(accepted ~ fBidPrem90 + BidCounts + BidApp + ThSize + fBidCW

+ Resistance + SolicitedByTarget + SizeRatio + DiffROA + VIXa + FedRateA

+ GDPa, data = mydata, family = "binomial")

null=glm(accepted ~ BidCounts + BidApp + Resistance, data = mydata,

family = "binomial")

step(full,scope=list(upper=full, lower=null),data=mydata,

direction="backward")

#Random assign to training data vs. test data

rej = mydata[mydata$Rejected == 1,]

acc = mydata[mydata$Rejected == 0,]

nrej = dim(rej)[1]

nacc = dim(acc)[1]

trainIndsR = sample(1:nrej,nrej/2+1)

testIndsR = setdiff(1:nrej, trainIndsR)

trainDataRej = rej[trainIndsR,]

testDataRej = rej[testIndsR,]

trainIndsA = sample(1:nacc,nacc/2)

testIndsA = setdiff(1:nacc, trainIndsA)

trainDataAcc = acc[trainIndsA,]

testDataAcc = acc[testIndsA,]

trainData = rbind(trainDataAcc, trainDataRej)

attach(trainData)

nrow(trainData)

testData = rbind(testDataAcc, testDataRej)

attach(testData)

nrow(testData)

#T-test

t.test(acc$TransactionValueMil, rej$TransactionValueMil)

t.test(acc$DiffROA, rej$DiffROA)

'66](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd1d54aa-e2a4-48fb-9ff6-755ecfc69e0e-161002205956/85/Phi-M-A-Thesis-76-320.jpg)