This dissertation by Jesús Salvador Cepeda Barrera focuses on the coordination of multiple robotic agents for disaster and emergency response, highlighting the role of multi-robot systems (MRS) in improving operational efficiency and effectiveness in crisis scenarios. The research presents a behavior-based control architecture to facilitate cooperative behavior among robots, aiming to enhance their capabilities in urban search and rescue missions. The findings demonstrate the potential for MRS to improve performance, adapt to dynamic environments, and increase the survival rates during critical response periods.

![List of Figures

1.1 Number of survivors and casualties in the Kobe earthquake in 1995. Image

from [267]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

1.2 Percentage of survival chances in accordance to when victim is located. Based

on [69]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

1.3 70 years for autonomous control levels. Edited from [44]. . . . . . . . . . . . 6

1.4 Mobile robot control scheme. Image from [255]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

1.5 Minsky’s interpretation of behaviors. Image from [188]. . . . . . . . . . . . 18

1.6 Classic and new artificial intelligence approaches. Edited from [255]. . . . . 18

1.7 Behavior in robotics control. Image from [138]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

1.8 Coordination methods for behavior-based control. Edited from [11]. . . . . . 19

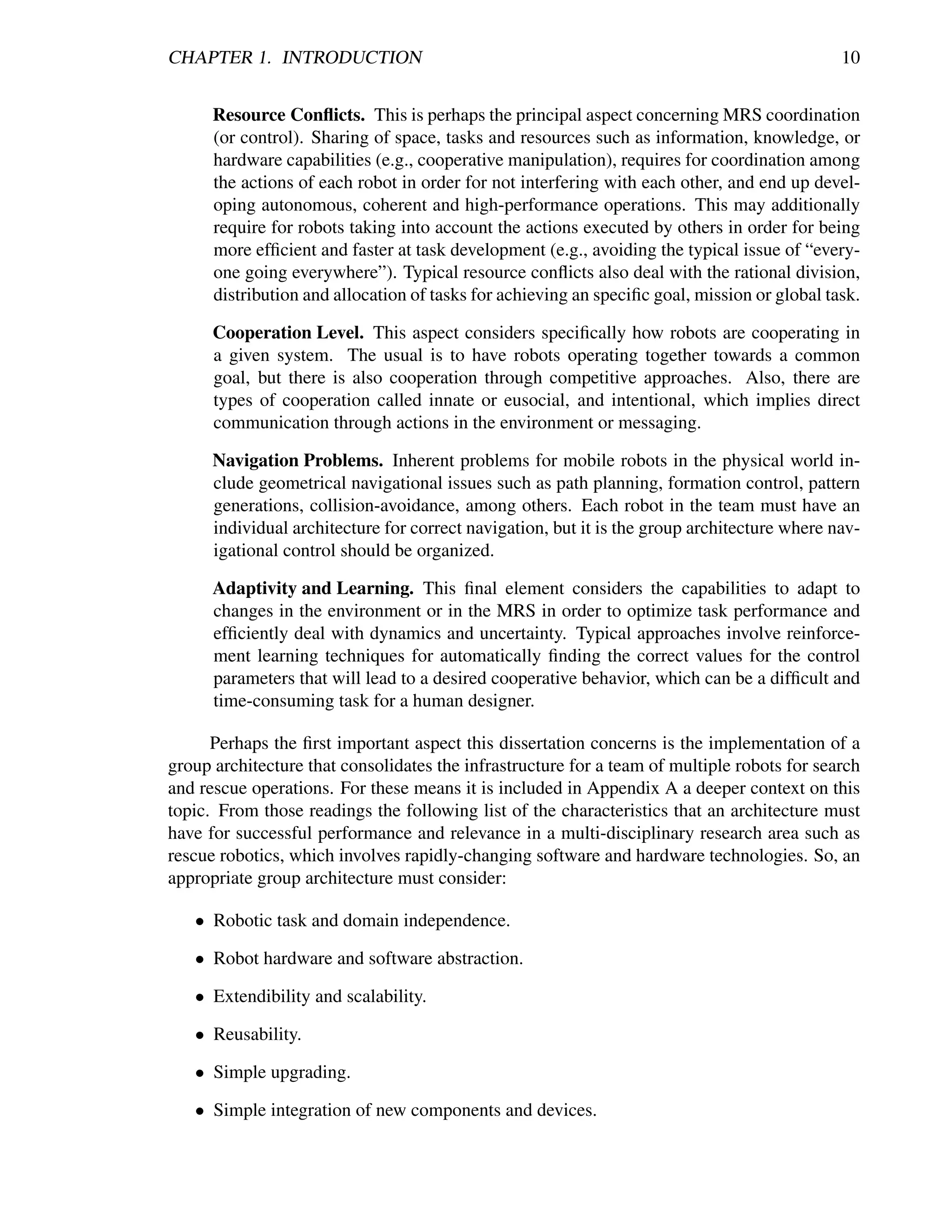

1.9 Group architecture overview. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

1.10 Service-oriented group architecture. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

2.1 Major challenges for networked robots. Image from [150]. . . . . . . . . . . 30

2.2 Typical USAR Scenario. Image from [267]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

2.3 Real pictures from the WTC Tower 2. a) shows a rescue robot within the white

box navigating in the rubble; b) robots-eye view with three sets of victim

remains. Image edited from [194] and [193]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

2.4 Typical problems with rescue robots. Image from [268]. . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

2.5 Template-based information system for disaster response. Image based on [156,

56]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

2.6 Examples of templates for disaster response. Image based on [156, 56]. . . . 42

2.7 Task force in rescue infrastructure. Image from [14]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

2.8 Rescue Communicator, R-Comm: a) Long version, b) Short version. Image

from [14]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

2.9 Handy terminal and RFID tag. Image from [14]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

2.10 Database for Rescue Management System, DaRuMa. Edited from [210]. . . . 44

2.11 RoboCup Rescue Concept. Image from [270]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

2.12 USARSim Robot Models. Edited from [284, 67]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

2.13 USARSim Disaster Snapshot. Edited from [18, 17]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

2.14 Sensor Readings Comparison. Top: Simulation, Bottom: Reality. Image

from [67]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

2.15 Control Architecture for Rescue Robot Systems. Image from [3]. . . . . . . . 50

2.16 Coordinated exploration using costs and utilities. Frontier assignment consid-

ering a) only costs; b) costs and utilities; c) three robots paths results. Edited

from [58]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

vi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-8-2048.jpg)

![2.17 Supervisor sketch for MRS patrolling. Image from [168]. . . . . . . . . . . . 53

2.18 Algorithm for determining occupancy grids. Image from [33]. . . . . . . . . 54

2.19 Multi-Robot generated maps in RoboCup Rescue 2007. Image from [225]. . . 55

2.20 Behavioral mapping idea. Image from [164]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

2.21 3D mapping using USARSim. Left) Kurt3D and its simulated counterpart.

Right) 3D color-coded map. Edited from [20]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

2.22 Face recognition in USARSim. Left) Successful recognition. Right) False

positive. Image from [20]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57

2.23 Human pedestrian vision-based detection procedure. Image from [90]. . . . . 57

2.24 Human pedestrian vision-based detection procedure. Image from hal.inria.fr/inria-

00496980/en/. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

2.25 Human behavior vision-based recognition. Edited from [207]. . . . . . . . . 58

2.26 Visual path following procedure. Edited from [103]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

2.27 Visual path following tests in 3D terrain. Edited from [103]. . . . . . . . . . 59

2.28 START Algorithm. Victims are sorted in: Minor, Delayed, Immediate and

Expectant; based on the assessment of: Mobility, Respiration, Perfusion and

Mental Status. Image from [80]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

2.29 Safety, security and rescue robotics teleoperation stages. Image from [36]. . . 61

2.30 Interface for multi-robot rescue systems. Image from [209]. . . . . . . . . . . 62

2.31 Desired information for rescue robot interfaces: a)multiple image displays, b)

multiple map displays. Edited from [292]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

2.32 Touch-screen technologies for rescue robotics. Edited from [185]. . . . . . . 64

2.33 MRS for autonomous exploration, mapping and deployment. a) the complete

heterogeneous team; b) sub-team with mapping capabilities. Image from [130]. 65

2.34 MRS result for autonomous exploration, mapping and deployment. a) origi-

nal floor map; b) robots collected map; c) autonomous planned deployment.

Edited from [130]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

2.35 MRS for search and monitoring: a) Piper J3 UAVs; b) heterogeneous UGVs.

Edited from [131]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

2.36 Demonstration of integrated search operations: a) robots at initial positions, b)

robots searching for human target, c) alert of target found, d) display nearest

UGV view of the target. Edited from [131]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

2.37 CRASAR MicroVGTV and Inuktun [91, 194, 158, 201]. . . . . . . . . . . . 70

2.38 TerminatorBot [282, 281, 204]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

2.39 Leg-in-Rotor Jumping Inspector [204, 267]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

2.40 Cubic/Planar Transformational Robot [266]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

2.41 iRobot ATRV - FONTANA [199, 91, 158]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

2.42 FUMA [181, 245]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

2.43 Darmstadt University - Monstertruck [8]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

2.44 Resko at UniKoblenz - Robbie [151]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

2.45 Independent [84]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

2.46 Uppsala University Sweden - Surt [211]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

2.47 Taylor [199]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

2.48 iRobot Packbot [91, 158]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74

2.49 SPAWAR Urbot [91, 158]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74

vii](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-9-2048.jpg)

![2.50 Foster-Miller Solem [91, 194, 158]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74

2.51 Shinobi - Kamui [189]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

2.52 CEO Mission II [277]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

2.53 Aladdin [215, 61]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

2.54 Pelican United - Kenaf [204, 216]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76

2.55 Tehzeeb [265]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76

2.56 ResQuake Silver2009 [190, 187]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76

2.57 Jacobs Rugbot [224, 85, 249]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

2.58 PLASMA-Rx [87]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

2.59 MRL rescue robots NAJI VI and NAJI VII [252]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

2.60 Helios IX and Carrier Parent and Child [121, 180, 267]. . . . . . . . . . . . . 78

2.61 KOHGA : Kinesthetic Observation-Help-Guidance Agent [142, 181, 189, 276]. 78

2.62 OmniTread OT-4 [40]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78

2.63 Hyper Souryu IV [204, 276]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

2.64 Rescue robots: a) Talon, b) Wolverine V-2, c) RHex, d) iSENSYS IP3, e)

Intelligent Aerobot, f) muFly microcopter, g) Chinese firefighting robot, h)

Teleoperated extinguisher, i) Unmanned surface vehicle, j) Predator, k) T-

HAWK, l) Bluefin HAUV. Images from [181, 158, 204, 267, 287]. . . . . . . 80

2.65 Jacobs University rescue arenas. Image from [249]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

2.66 Arena in which multiple Kenafs were tested. Image from [205]. . . . . . . . 82

2.67 Exploration strategy and centralized, global 3D map: a) frontiers in current

global map, b) allocation and path planning towards the best frontier, c) a

final 3D global map. Image from [205]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82

2.68 Mapping data: a) raw from individual robots, b) fused and corrected in a new

global map. Image from [205]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

2.69 Building exploration and temperature gradient mapping: a) robots as mobile

sensors navigating and deploying static sensors, b) temperature map. Image

from [144]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

2.70 Building structure exploration and temperature mapping using static sensors,

human mobile sensor, and UAV mobile sensor. Image from [98]. . . . . . . . 84

2.71 Helios IX in a door-opening procedure. Image from [121]. . . . . . . . . . . 85

2.72 Real model and generated maps of the 60 m. hall: a) real 3D model, b)

generated 3D map with snapshots, c) 2D map with CPS, d) 2D map with dead

reckoning. Image from [121]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

2.73 IRS-U and K-CFD real tests with rescue robots: a) deployment of Kohga

and Souryu robots, b) Kohga finding a victim, c) operator being notified of

victim found, d) Kohga waiting until human rescuer assists the victim, e)

Souryu finding a victim, f) Kohga and Souryu awaiting for assistance, g) hu-

man rescuers aiding the victim, and h) both robots continue exploring. Images

from [276]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

2.74 Types of entries in mine rescue operations: a) Surface Entry (SE), b) Borehole

Entry (BE), c) Void Entry (VE), d) Inuktun being deployed in a BE [201]. . . 89

2.75 Standardized test arenas for rescue robotics: a) Red Arena, b) Orange Arena,

c) Yellow Arena. Image from [67]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

viii](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-10-2048.jpg)

![3.1 MaSE Methodology. Image from [289]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94

3.2 USAR Requirements (most relevant references to build this diagram include:

[261, 19, 80, 87, 254, 269, 204, 267, 268]). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

3.3 Sequence Diagram I: Exploration and Mapping (most relevant references to

build this diagram include: [173, 174, 175, 176, 21, 221, 86, 232, 10, 58, 271,

101, 33, 240, 92, 126, 194, 204]). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

3.4 Sequence Diagram IIa: Recognize and Identify - Local (most relevant refer-

ences to build this diagram include: [170, 175, 221, 23, 242, 163, 90, 207, 89,

226]). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

3.5 Sequence Diagram IIb: Recognize and Identify - Remote (most relevant ref-

erences to build this diagram include: [170, 175, 221, 23, 242, 163, 90, 207,

89, 226]). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

3.6 Sequence Diagram III: Support and Relief (most relevant references to build

this diagram include: [58, 33, 80, 19, 226, 150, 267, 204, 87, 254]). . . . . . . 102

3.7 Robots used in this dissertation: to the left a simulated version of an Adept

Pioneer 3DX, in the middle the real version of an Adept Pioneer 3AT, and to

the right a Dr. Robot Jaguar V2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

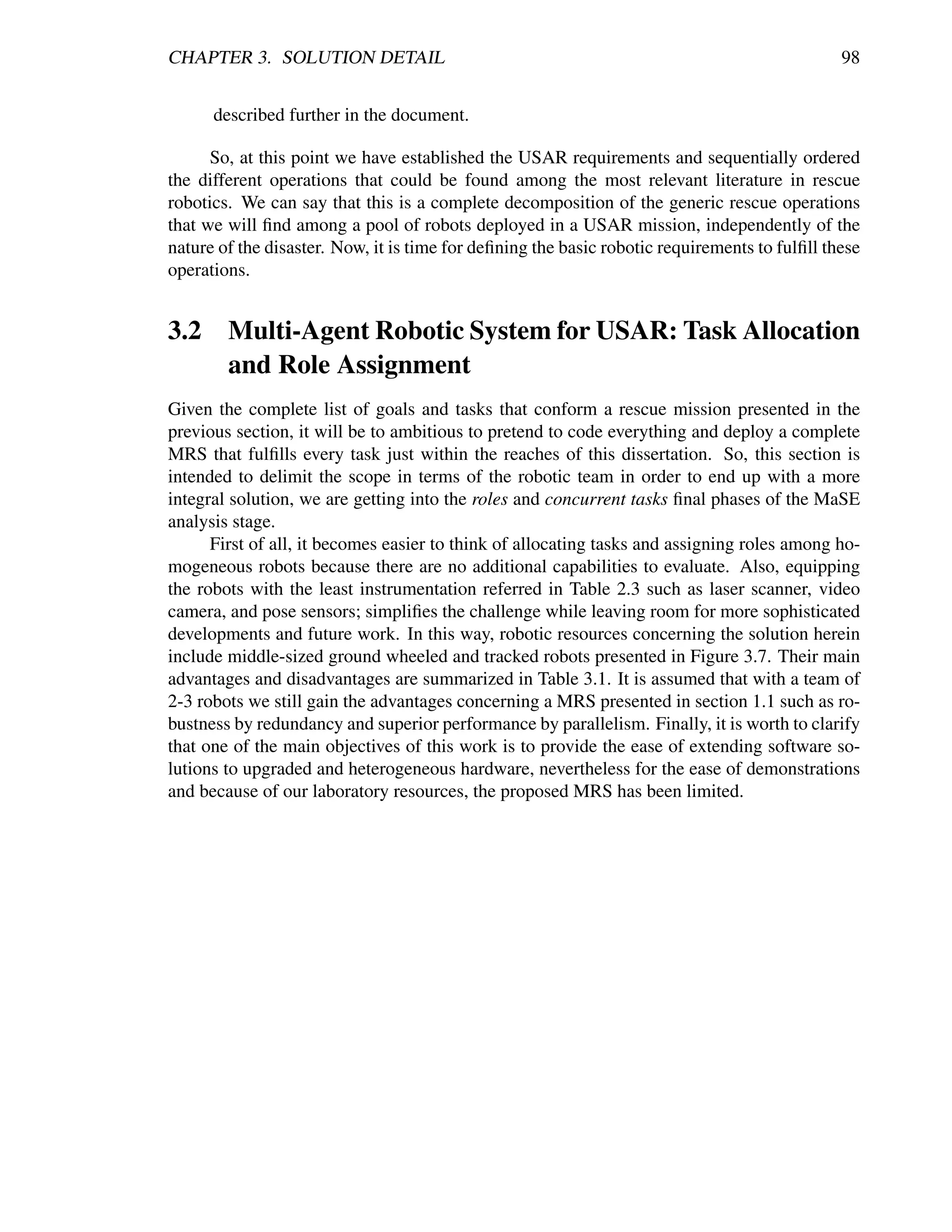

3.8 Roles, behaviors and actions mappings. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

3.9 Roles, behaviors and actions mappings. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

3.10 Behavior-based control architecture for individual robots. Edited image from [178].108

3.11 The Hybrid Paradigm. Image from [192]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109

3.12 Group architecture. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110

3.13 Architecture topology: at the top the system element communicating wireless

with the subsystems. Subsystems include their nodes, which can be differ-

ent types of computers. Finally, components represent the running software

services depending on the existing hardware and node’s capabilities. . . . . . 112

3.14 Microsoft Robotics Developer Studio principal components. . . . . . . . . . 114

3.15 CCR Architecture: when a message is posted into a given Port or PortSet,

triggered Receivers call for Arbiters subscribed to the messaged port in order

for a task to be queued and dispatched to the threading pool. Ports defined as

persistent are concurrently being listened, while non-persistent are one-time

listened. Image from [137]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 116

3.16 DSS Architecture. The DSS is responsible for loading services and manag-

ing the communications between applications through the Service Forwarder.

Services could be distributed in a same host and/or through the network. Im-

age from [137]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 117

3.17 MSRDS Operational Schema. Even though DSS is on top of CCR, many

services access CCR directly, which at the same time is working on low level

as the mechanism for orchestration to happen, so it is placed sidewards to the

DSS. Image from [137]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 118

ix](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-11-2048.jpg)

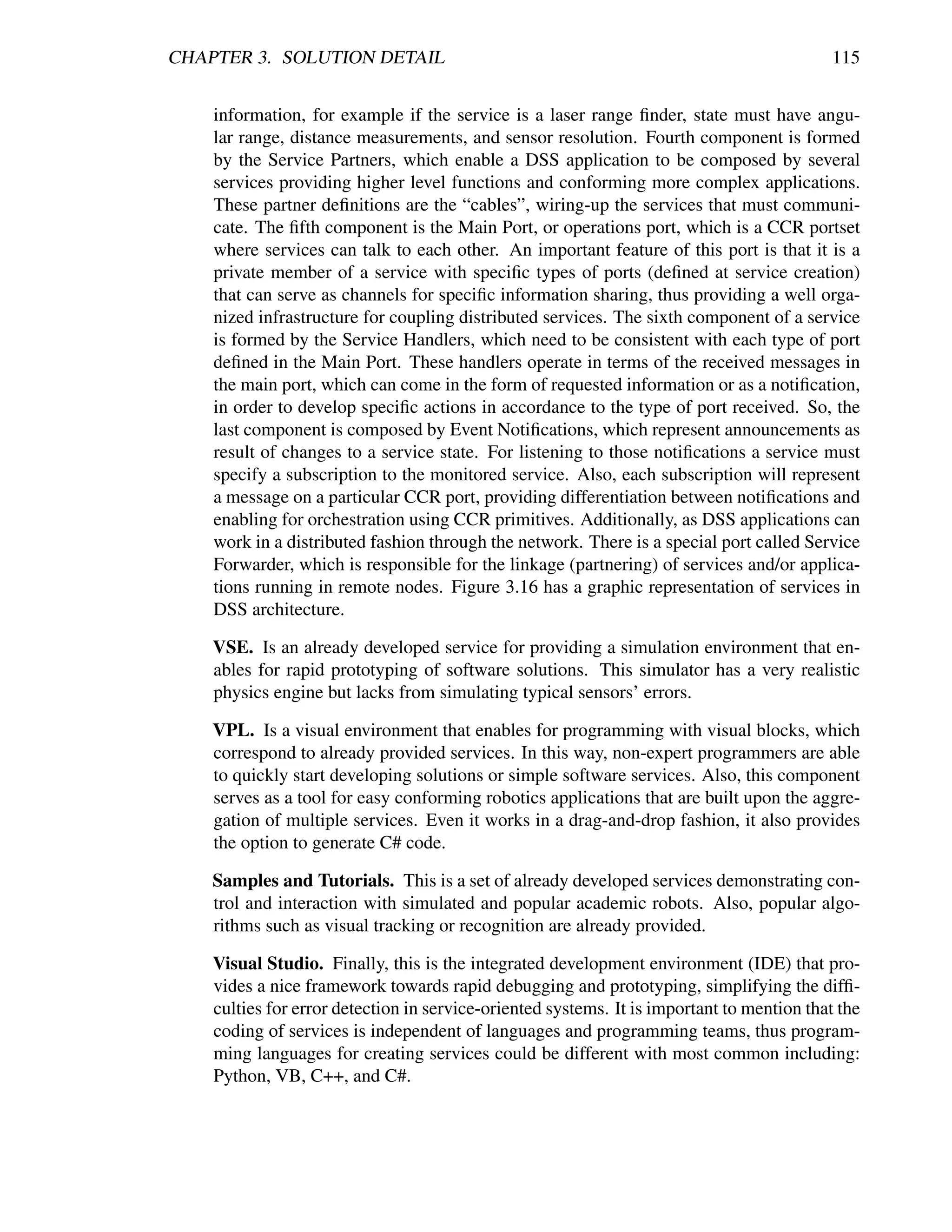

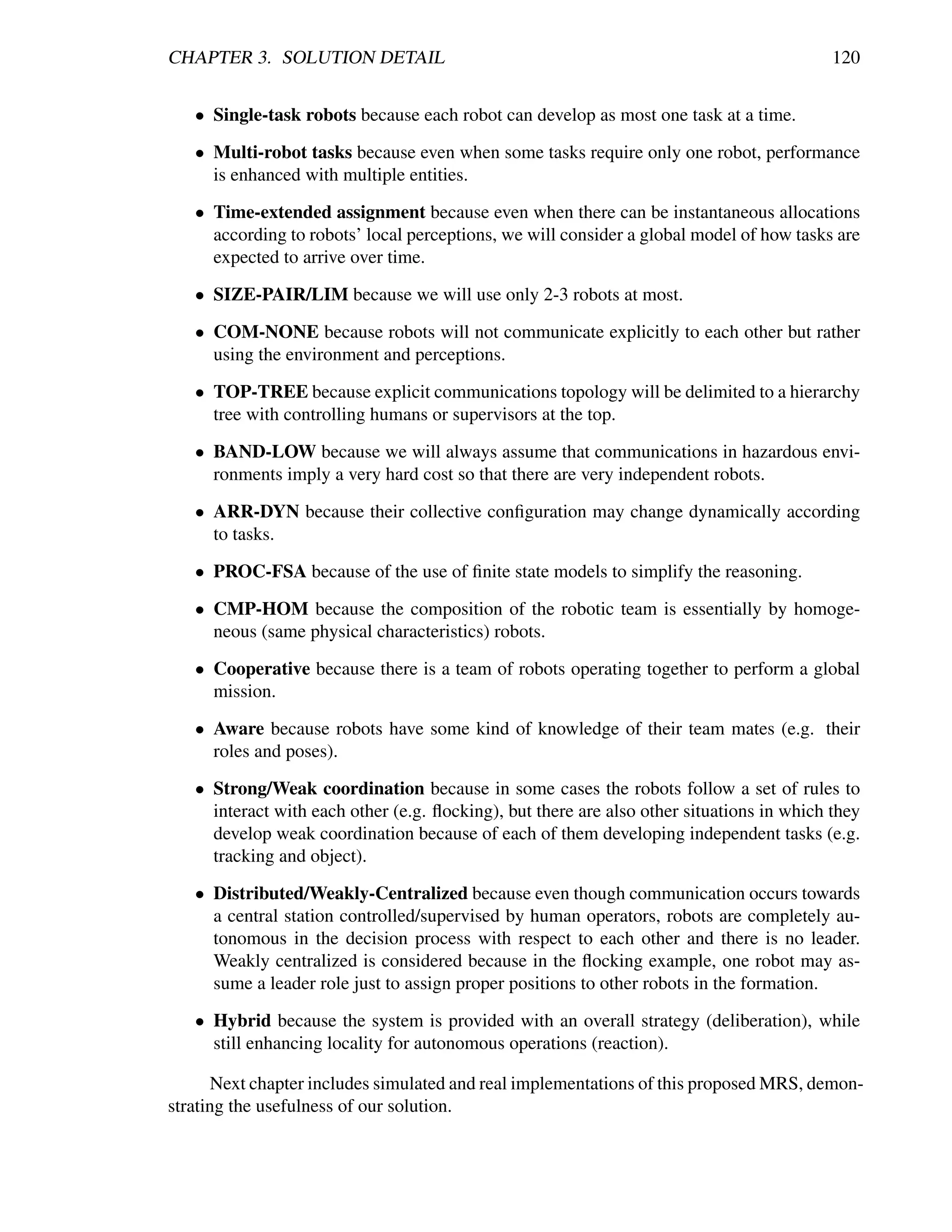

![3.18 Behavior examples designed as services. Top represents the handle collision

behavior, which according to a goal/current heading and the laser scanner sen-

sor, it evaluates the possible collisions and outputs the corresponding steering

and driving velocities. Middle represents the detection (victim/threat) behav-

ior, which according to the attributes to recognize and the camera sensor, it

implements the SURF algorithm and outputs a flag indicating if the object

has been found and the attributes that correspond. Bottom represents the seek

behavior, which according to a goal position, its current position and the laser

scanner sensor, it evaluates the best heading using the VFH algorithm and

then outputs the corresponding steering and driving velocities. . . . . . . . . 119

4.1 Process to Quick Simulation. Starting from a simple script in SPL we can

decide which is more useful for our robotic control needs and programming

skills, either going through C# or VPL. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122

4.2 Created service for fast simulations with maze-like scenarios. Available at

http://erobots.codeplex.com/. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123

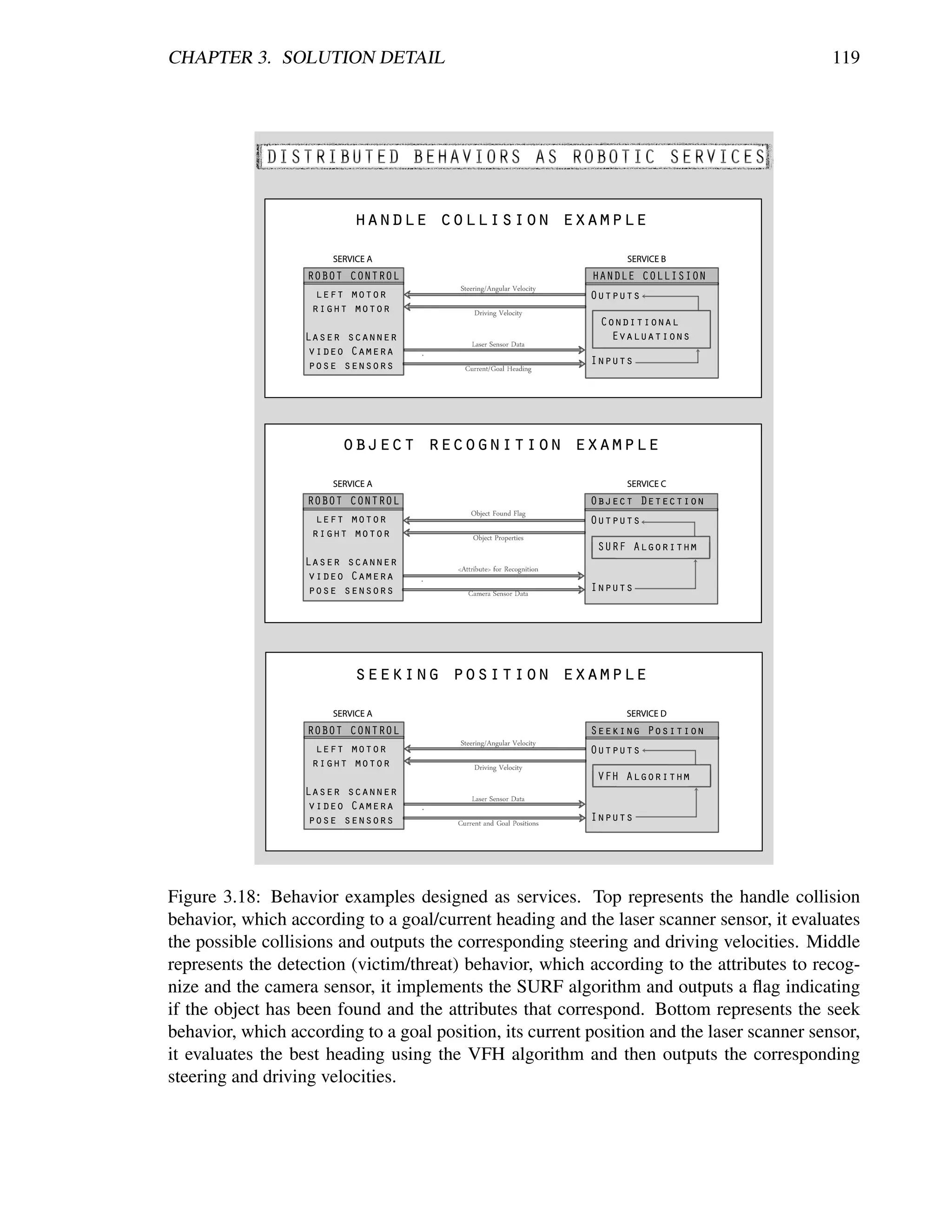

4.3 Fast simulation to real implementation process. It can be seen that going from

a simulated C# service to real hardware implementations is a matter of chang-

ing a line of code: the service reference. Concerning VPL, simulated and real

services are clearly identified providing easy interchange for the desired test. . 124

4.4 Local and remote approaches used for the experiments. . . . . . . . . . . . . 124

4.5 Speech recognition service experiment for voice-commanded robot naviga-

tion. Available at http://erobots.codeplex.com/. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

4.6 Vision-based recognition service experiment for visual-joystick robot naviga-

tion. Available at http://erobots.codeplex.com/. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 126

4.7 Wall-follow behavior service. View is from top, the red path is made of a robot

following the left (white) wall in the maze, while the blue one corresponds to

another robot following the right wall. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127

4.8 Seek behavior service. Three robots in a maze viewed from the top, one static

and the other two going to specified goal positions. The red and blue paths

are generated by each one of the navigating robots. To the left of the picture a

simple console for appreciating the VFH [41] algorithm operations. . . . . . 127

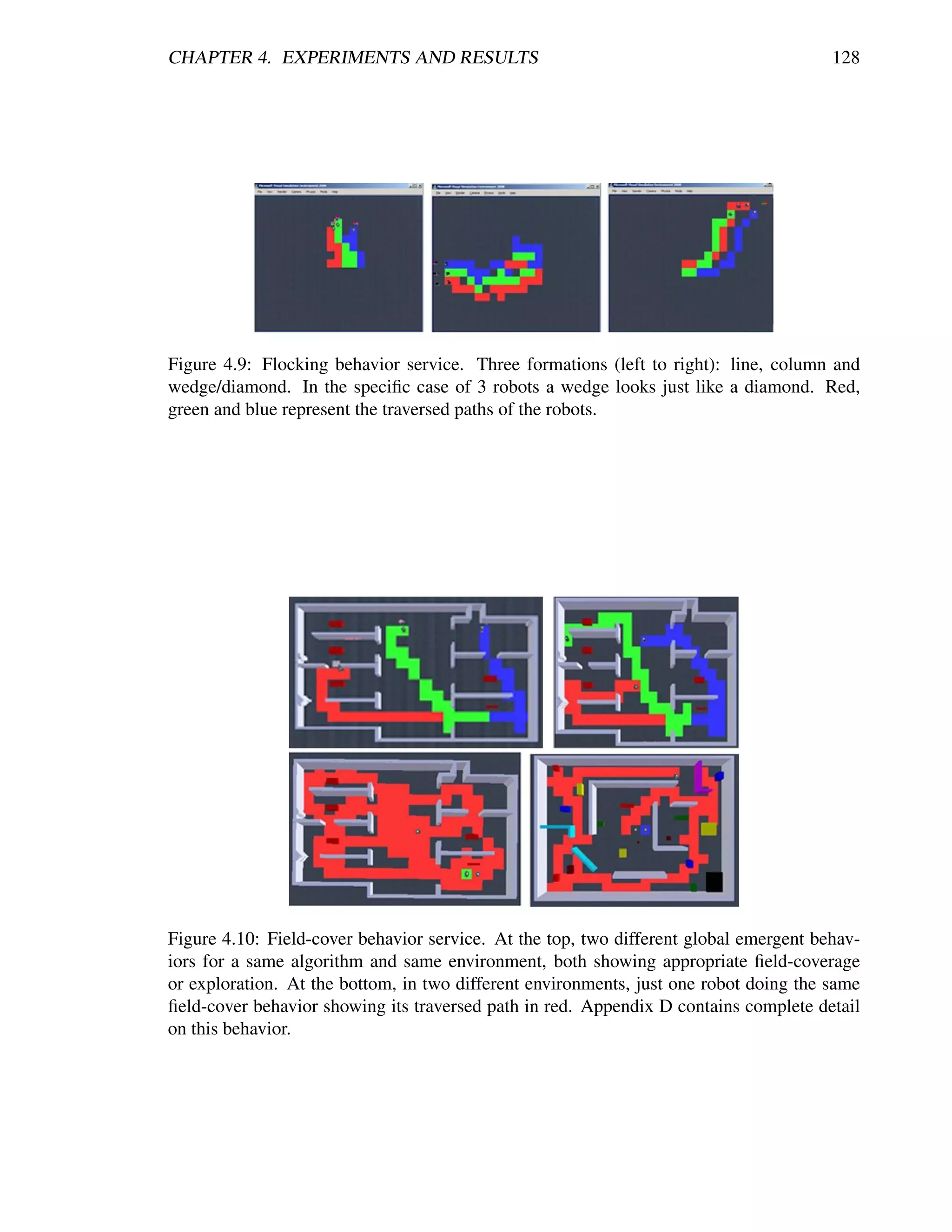

4.9 Flocking behavior service. Three formations (left to right): line, column and

wedge/diamond. In the specific case of 3 robots a wedge looks just like a

diamond. Red, green and blue represent the traversed paths of the robots. . . 128

4.10 Field-cover behavior service. At the top, two different global emergent behav-

iors for a same algorithm and same environment, both showing appropriate

field-coverage or exploration. At the bottom, in two different environments,

just one robot doing the same field-cover behavior showing its traversed path

in red. Appendix D contains complete detail on this behavior. . . . . . . . . . 128

4.11 Victim and Threat behavior services. Being limited to vision-based detection,

different figures were used to simulate threats and victims according to recent

literature [116, 20, 275, 207]. To recognize them, already coded algorithms

were implemented including SURF [26], HoG [90] and face-detection [279]

from the popular OpenCV [45] and EmguCV [96] libraries. . . . . . . . . . . 129

x](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-12-2048.jpg)

![4.12 Simultaneous localization and mapping features for the MSRDS VSE. Robot

1 is the red path, robot 3 the green and robot 3 the blue. They are not only

mapping the environment by themselves, but also contributing towards a team

map. Nevertheless localization is a simulation cheat and laser scanners have

no uncertainty as they will have in real hardware. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130

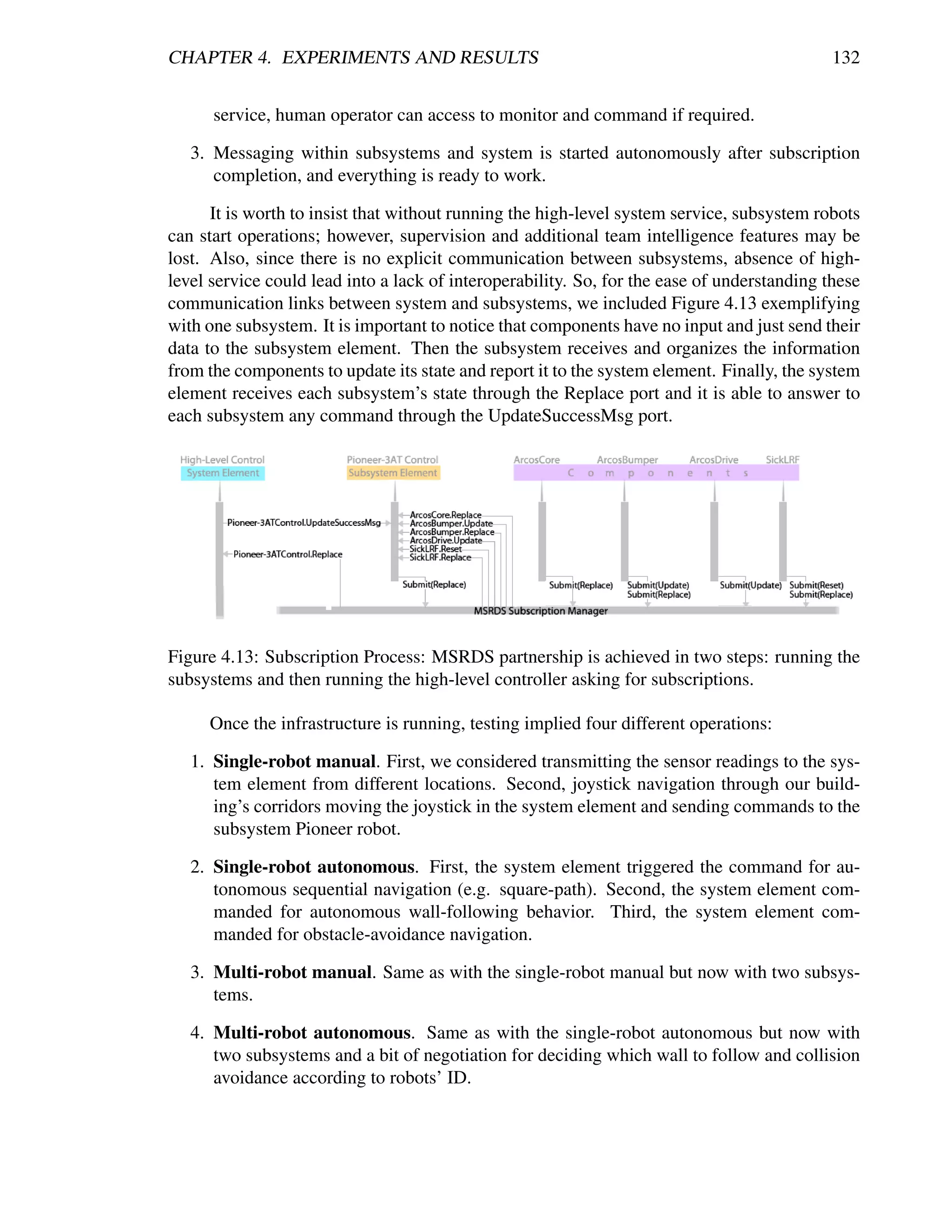

4.13 Subscription Process: MSRDS partnership is achieved in two steps: running

the subsystems and then running the high-level controller asking for subscrip-

tions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132

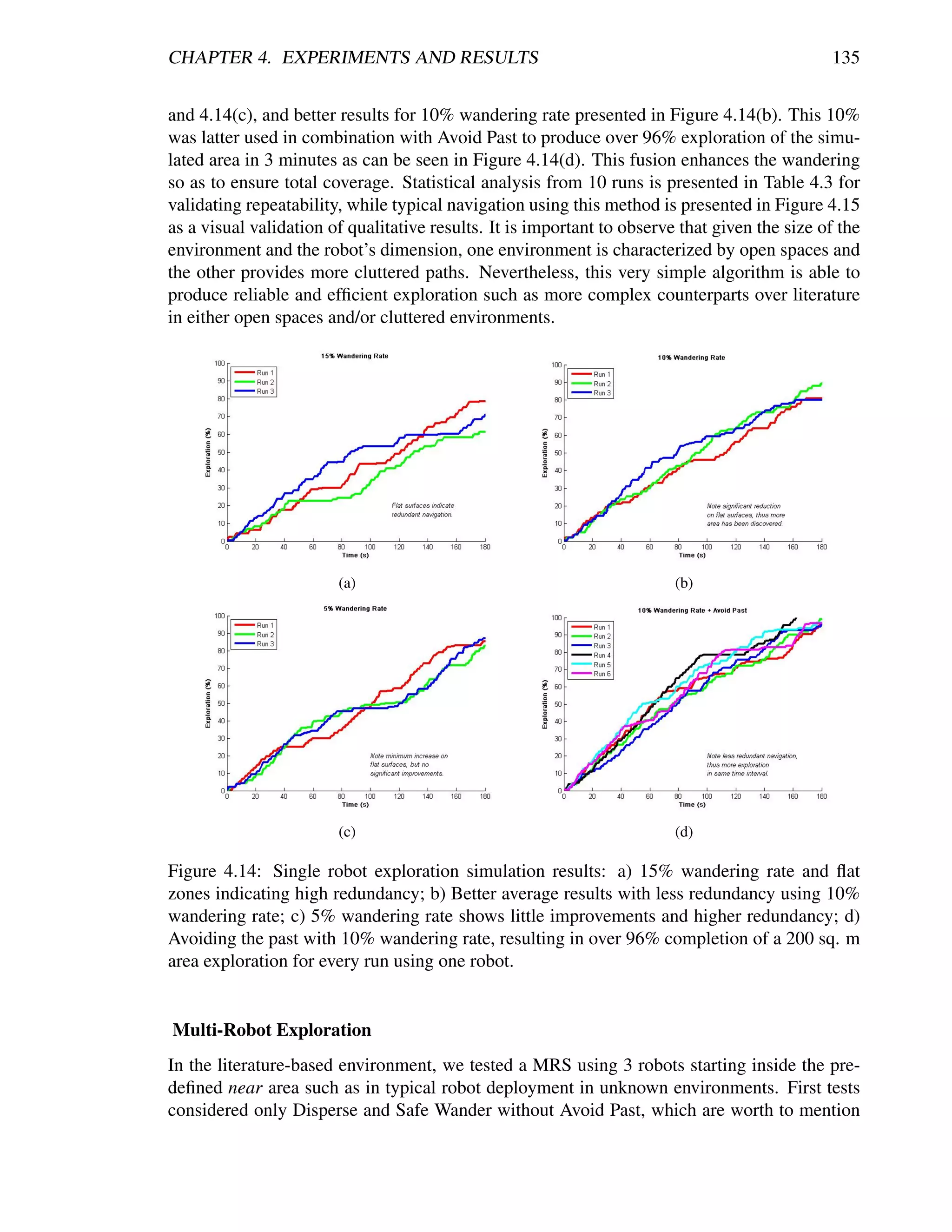

4.14 Single robot exploration simulation results: a) 15% wandering rate and flat

zones indicating high redundancy; b) Better average results with less redun-

dancy using 10% wandering rate; c) 5% wandering rate shows little improve-

ments and higher redundancy; d) Avoiding the past with 10% wandering rate,

resulting in over 96% completion of a 200 sq. m area exploration for every

run using one robot. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 135

4.15 Typical navigation for qualitative appreciation: a) The environment based

upon Burgard’s work in [58]; b) A second more cluttered environment. Snap-

shots are taken from the top view and the traversed paths are drawn in red.

For both scenarios the robot efficiently traverses the complete area using the

same algorithm. Black circle with D indicates deployment point. . . . . . . . 136

4.16 Autonomous exploration showing representative results in a single run for 3

robots avoiding their own past. Full exploration is completed at almost 3 times

faster than using a single robot, and the exploration quality shows a balanced

result meaning an efficient resources (robots) management. . . . . . . . . . . 137

4.17 Autonomous exploration showing representative results in a single run for 3

robots avoiding their own and teammates’ past. Results show more interfer-

ence and imbalance at exploration quality when compared to avoiding their

own past only. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 138

4.18 Qualitative appreciation: a) Navigation results from Burgard’s work [58]; b)

Our gathered results. Path is drawn in red, green and blue for each robot.

High similarity with a much simpler algorithm can be appreciated. Black

circle with D indicates deployment point. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 138

4.19 The emergent in-zone coverage behavior for long time running the exploration

algorithm. Each color (red, green and blue) shows an area explored by a

different robot. Black circle with D indicates deployment point. . . . . . . . 139

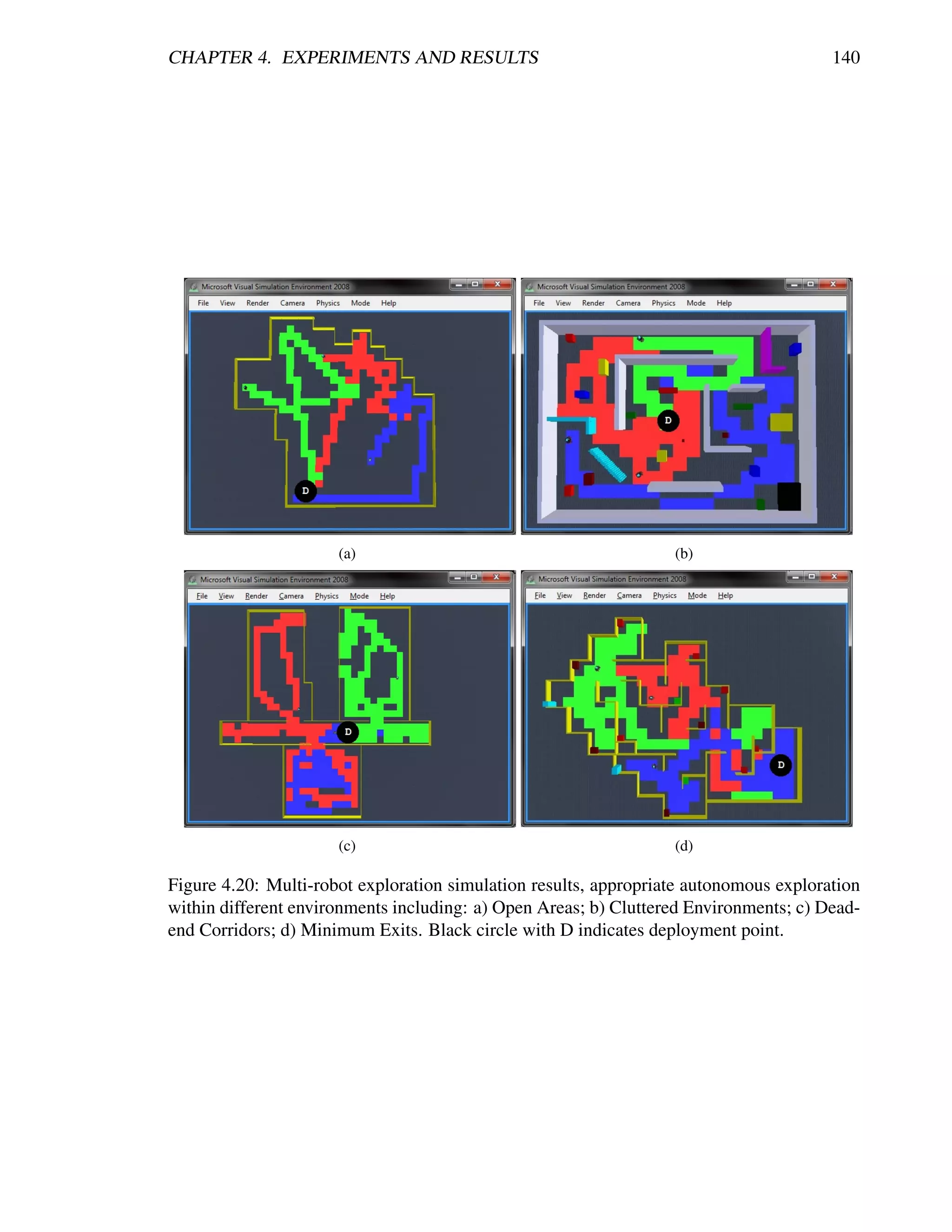

4.20 Multi-robot exploration simulation results, appropriate autonomous explo-

ration within different environments including: a) Open Areas; b) Cluttered

Environments; c) Dead-end Corridors; d) Minimum Exits. Black circle with

D indicates deployment point. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 140

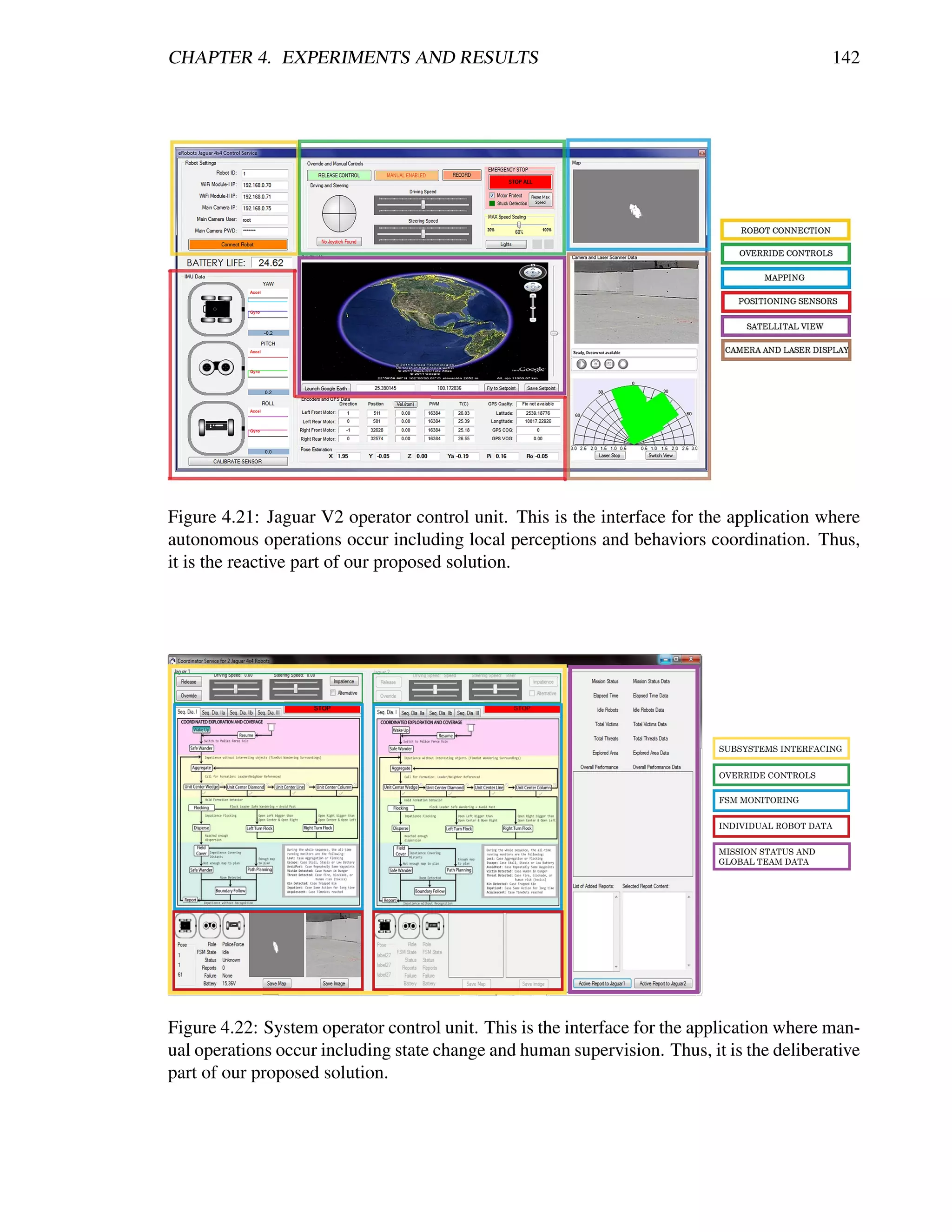

4.21 Jaguar V2 operator control unit. This is the interface for the application where

autonomous operations occur including local perceptions and behaviors coor-

dination. Thus, it is the reactive part of our proposed solution. . . . . . . . . 142

4.22 System operator control unit. This is the interface for the application where

manual operations occur including state change and human supervision. Thus,

it is the deliberative part of our proposed solution. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142

4.23 Template structure for creating and managing reports. Based on [156, 56]. . . 143

xi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-13-2048.jpg)

![4.24 Deployment of a Jaguar V2 for single robot autonomous exploration experi-

ments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 144

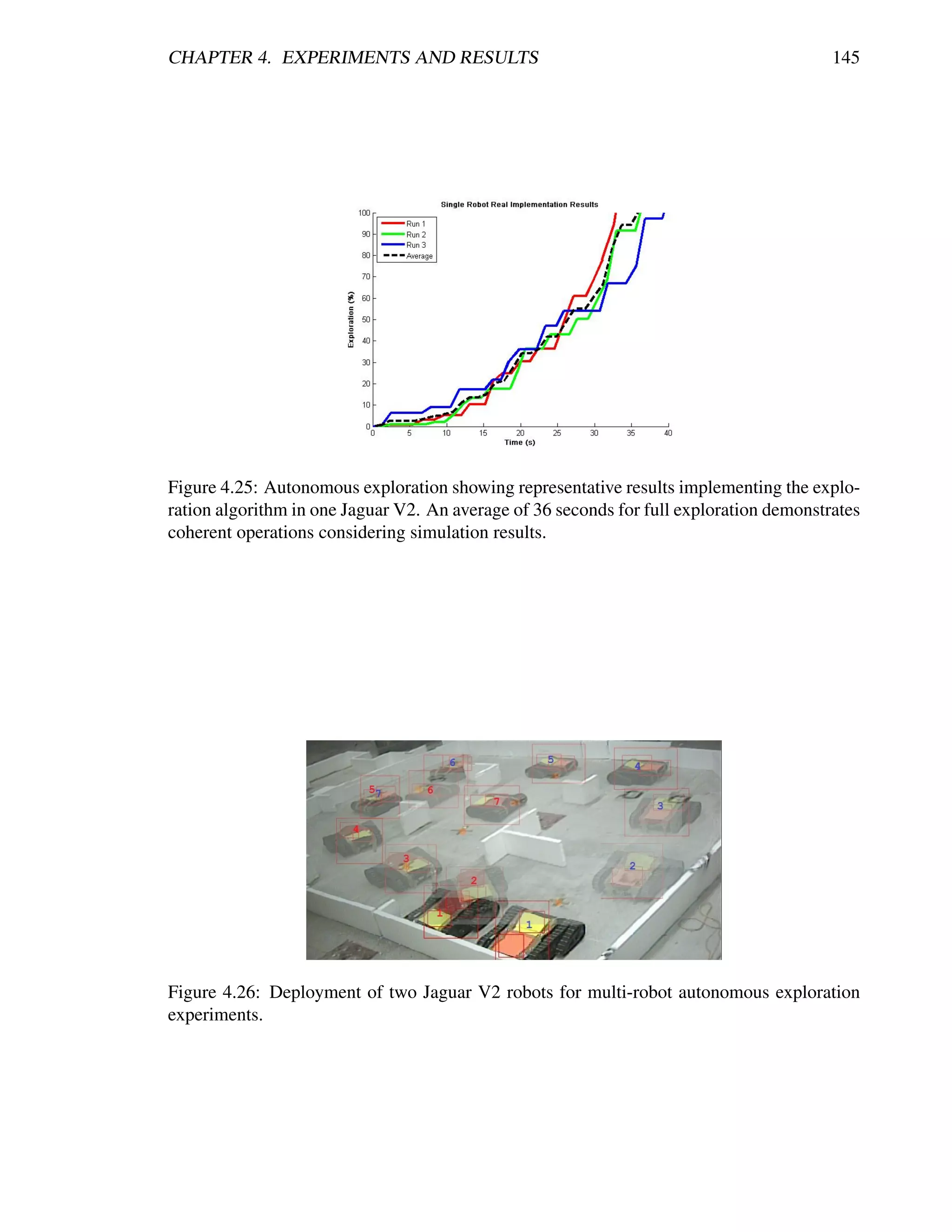

4.25 Autonomous exploration showing representative results implementing the ex-

ploration algorithm in one Jaguar V2. An average of 36 seconds for full ex-

ploration demonstrates coherent operations considering simulation results. . . 145

4.26 Deployment of two Jaguar V2 robots for multi-robot autonomous exploration

experiments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 145

4.27 Autonomous exploration showing representative results for a single run using

2 robots avoiding their own past. An almost half of the time for full explo-

ration when compared to single robot runs demonstrates efficient resource

management. The resultant exploration quality shows the trend towards per-

fect balancing between the two robots. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146

4.28 Comparison between: a) typical literature exploration process and b) our pro-

posed exploration. Clear steps and complexity reduction can be appreciated

between sensing and acting. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 147

A.1 Generic single robot architecture. Image from [2]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 154

A.2 Autonomous Robot Architecture - AuRa. Image from [12]. . . . . . . . . . . 155

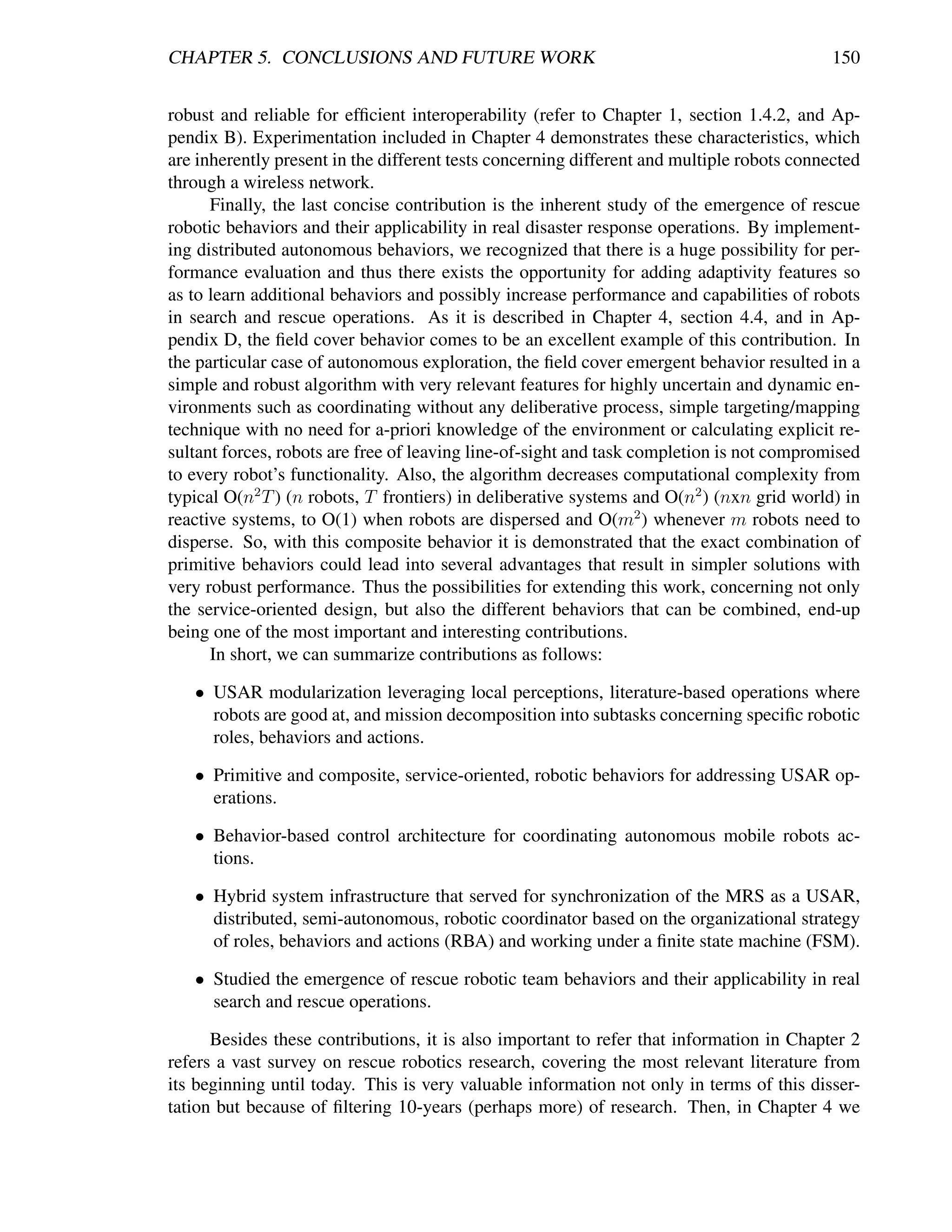

D.1 8 possible 45◦ heading cases with 3 neighbor waypoints to evaluate so as to

define a CCW, CW or ZERO angular acceleration command. For example,

if heading in the -45◦ case, the neighbors to evaluate are B, C and D, as left,

center and right, respectively. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 181

D.2 Implemented 2-state Finite State Automata for autonomous exploration. . . . 184

xii](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-14-2048.jpg)

![List of Tables

1.1 Comparison of event magnitude. Edited from [182]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

1.2 Important concepts and characteristics on the control of multi-robot systems.

Based on [53, 11, 2, 24]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

1.3 FSA, FSM and BBC relationships. Edited from [192]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

1.4 Components of a hybrid-intelligence architecture. Based on [192]. . . . . . . 21

1.5 Nomenclature. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

1.6 Relevant metrics in multi-robot systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

2.1 Factors influencing the scope of the disaster relief effort from [83]. . . . . . . 40

2.2 A classification of robotic behaviors. Based on [178, 223]. . . . . . . . . . . 51

2.3 Recommendations for designing a rescue robot [37, 184, 194, 33, 158, 201, 267]. 69

3.1 Main advantages and disadvantages for using wheeled and tracked robots [255,

192]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

4.1 Experiments’ results: average delays . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133

4.2 Metrics used in the experiments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134

4.3 Average and Standard Deviation for full exploration time in 10 runs using

Avoid Past + 10% wandering rate with 1 robot. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 136

4.4 Average and Standard Deviation for full exploration time in 10 runs using

Avoid Past + 10% wandering rate with 3 robots. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137

4.5 Average and Standard Deviation for full exploration time in 10 runs using

Avoid Kins Past + 10% wandering rate with 3 robots. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 138

B.1 Comparison among different software systems engineering techniques [219,

46, 82, 293, 4]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161

C.1 Wake up behavior. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162

C.2 Resume behavior. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 163

C.3 Wait behavior. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 163

C.4 Handle Collision behavior. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 164

C.5 Avoid Past behavior. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 164

C.6 Locate behavior. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 165

C.7 Drive Towards behavior. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 165

C.8 Safe Wander behavior. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 166

C.9 Seek behavior. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 166

C.10 Path Planning behavior. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 167

xiii](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-15-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 1

Introduction

“One can expect the human race to continue attempting systems just within or

just beyond our reach; and software systems are perhaps the most intricate

and complex of man’s handiworks. The management of this complex craft

will demand our best use of new languages and systems, our best adaptation

of proven engineering management methods, liberal doses of common sense,

and a God-given humility to recognize our fallibility and limitations.”

– Frederick P. Brooks, Jr. (Computer Scientist)

C HAPTER O BJECTIVES

— Why this dissertation.

— What we are dealing with.

— What we are solving.

— How we are solving it.

— Where we are contributing.

— How the document is organized.

In recent years, the use of Multi-Robot Systems (MRS) has become popular for several

application domains such as military, exploration, surveillance, search and rescue, and even

home and industry automation. The main reason for using these MRS is that they are a

convenient solution in terms of costs, performance, efficiency, reliability, and reduced human

exposure to harmful environments. In that way, existing robots and implementation domains

are of increasing number and complexity, turning coordination and cooperation fundamental

features among robotics research [99].

Accordingly, developing a team of cooperative autonomous mobile robots with efficient

performance has been one of the most challenging goals in artificial intelligence. The co-

ordination and cooperation of MRS has involved state of the art problems such as efficient

navigation, multi-robot path planning, exploration, traffic control, localization and mapping,

formation and docking control, coverage and flocking algorithms, target tracking, individual

and team cognition, tasks’ analysis, efficient resource management, suitable communications,

among others. As a result, research has witnessed a large body of significant advances in

the control of single mobile robots, dramatically improving the feasibility and suitability of

cooperative robotics. These vast scientific contributions created the need for coupling these

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-19-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 2

advances, leading researchers to develop inter-robot communication frameworks. Finding a

framework for cooperative coordination of multiple mobile robots that ensures the autonomy

and the individual requirements of the involved robots has always been a challenge too.

Moreover, considering all possible environments where robots interact, disaster scenar-

ios come to be among the most challenging ones. These scenarios, either man-made or natu-

ral, have no specific structure and are highly dynamic, uncertain and inherently hostile. These

disastrous events like: earthquakes, floods, fires, terrorist attacks, hurricanes, trapped popu-

lations, or even chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear explosions(CBRN or CBRNE);

involve devastating effects on wildlife, biodiversity, agriculture, urban areas, human health,

and also economy. So, the rapidly acting to save lives, avoid further environmental damage

and restore basic infrastructure has been among the most serious social issues for the intellec-

tual community.

For that reason, technology-based solutions for disaster and emergency situations are

main topics for relevant international associations, which had created specific divisions for

research on this area such as IEEE Safety, Security and Rescue Robotics (IEEE SSRR)

and the RoboCup Rescue, both active since 2002. Therefore, this dissertation focuses on

an improvement for disaster response and recovery, encouraging the relationship between

multiple robots as an important tool for mitigating disasters by cooperation, coordination and

communication among them and human operators.

1.1 Motivation

Historically, rescue robotics began in 1995 with one of the most devastating urban disasters

in the 20th century: the Hanshin-Awajii earthquake in January 17th in Kobe, Japan. Accord-

ing to [267], this disaster claimed more than 6,000 human lives, affected more than 2 million

people, damaged more than 785,000 houses, direct damage costs were estimated above 100

billion USD, and death rates reached 12.5% in some regions. The same year robotics re-

searchers in the US pushed the idea of the new research field while serving as rescue workers

at the bombing of the Murrah federal building in Oklahoma City [91]. Then, the 9/11 events

consolidated the area by being the first known place in the world to have real implementations

of rescue robots searching for victims and paths through the rubble, inspecting structures, and

looking for hazardous materials [194]. Additionally, the 2005 World Disasters report [283]

indicates that between 1995 and 2004 more than 900,000 human lives were lost and direct

damage costs surpassed the 738 billion USD, just in urban disasters. Merely indicating that

something needs and can be done.

Furthermore, these incidents as well as other mentioned disasters can also put the res-

cuers at risk of injury or death. In Mexico City the 1985 earthquake killed 135 rescuers during

disaster response operations [69]. In the World Trade Center in 2001, 402 rescuers lost their

lives [184]. More recently in March 2011, in the nuclear disaster in Fukushima, Japan [227]

rescuers were not even allowed to enter the ravaged area because it implied critical radiation

exposure. So, the rescue task is dangerous and time consuming, with the risk of further prob-

lems arising on the site [37]. To reduce these additional risks to the rescuers and victims,

the search is carried out slowly and delicately provoking a direct impact on the time to locate](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-20-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 3

survivors. Typically, the mortality rate increases and peaks the second day, meaning that sur-

vivors who are not located in the first 48 hours after the event are unlikely to survive beyond

a few weeks in the hospital [204]. Figure 1.1 shows the survivors rescued in the Kobe earth-

quake. As can be seen, beyond the third day there are almost no more victims rescued. Then,

Figure 1.2 shows the average survival chances in a urban disaster according to the days after

the incident. It can be appreciated that after the first day the chances of surviving are dramati-

cally decreased by more than 40%, and also after the third day another critical decrease shows

no more than 30% chances of surviving. So, there is a clear urgency for rescuers in the first

3 days where chances are good for raising survival rate, thus giving definition to the popular

term among rescue teams of “72 golden hours”.

Figure 1.1: Number of survivors and casualties in the Kobe earthquake in 1995. Image

from [267].

Figure 1.2: Percentage of survival chances in accordance to when victim is located. Based

on [69].

Consequently, real catastrophes and international contributions within the IEEE SSRR

and the RoboCup Rescue lead researchers to define the main usage of robotics in the so called](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-21-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 4

Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) missions. The essence of USAR is to save lives but,

Robin Murphy and Satoshi Tadokoro, two of the major contributors in the area, refer the

following possibilities for robots operating in urban disasters [204, 267]:

Search. Aimed to gather information on the disaster, locate victims, dangerous ma-

terials or any potential hazards in a faster way without increasing risks for secondary

damages.

Reconnaissance and mapping. For providing situational awareness. It is broader than

search in the way that it creates a reference of the ravaged zone in order to aid in the

coordination of the rescue effort, thus increasing the speed of the search, decreasing the

risk to rescue workers, and providing a quantitative investigation of damage at hand.

Rubble removal. Using robotics can be faster than manually and with a smaller foot-

print (e.g., exoskeletons) than traditional construction cranes.

Structural inspection. Providing better viewing angles at closer distances without ex-

posing the rescuers nor the survivors.

In-situ medical assessment and intervention. Since medical doctors may not be per-

mitted inside the critical ravaged area, called hot zone, robotic medical aid ranges from

verbal interactions, visual inspections and transporting medications; to complete sur-

vivors’ diagnosis and telemedicine. This is perhaps the most challenging task for robots.

Acting as a mobile beacon or repeater. Serve as landmark for localization and ren-

dezvous purposes or simply extending the wireless communication ranges.

Serving as a surrogate. Decreasing the risk to the rescue workers, robots may be used

as sensor extensions for enhancing rescuers’ perceptions enabling them to remotely

gather information of the zone and monitor other rescuers progress and needs.

Adaptively shoring unstable rubble. In order to prevent secondary collapse and avoid-

ing higher risks for rescuers and survivors.

Providing logistics support. Provide recovery actions and assistance by autonomously

transporting equipment, supplies and goods from storage areas to distribution points and

evacuation and assistance centres.

Instant deployment. Avoiding the initial overall evaluations for letting human rescuers

to go on site, robots can go instantly, thus improving speed of operations in order to raise

survival rate.

Other. General uses may suggest robots doing particular operations that are impossible

or difficult to perform by humans, as they can enter smaller areas and operate without

breaks. Also, robots can operate for long periods in harsher conditions in a more ef-

ficient way than humans do (e.g., they don’t need water or food, no need to rest, no

distractions, and the only fatigue is power running low).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-22-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 5

In the same line, multi-agent robotic systems (MARS, or simply MRS) have inherent

characteristics that come to be of huge benefit for USAR implementations. According to [159]

some remarkable properties of these systems are:

Diversity. They apply to a large range of tasks and domains. Thus, they are a versatile

tool for disaster and emergency support where tasks are plenty.

Greater efficiency. In general, MRS exchanging information and cooperating tend to

be more efficient than a single robot.

Improved system performance. It has been demonstrated that multiple robots finish

tasks faster and more accurately than a single robot.

Fault tolerance. Using redundant units makes a system more tolerable to failures by

enabling possible replacements.

Robustness. By introducing redundancy and fault tolerance, a task is lesser compro-

mised and thus the system is more robust.

Lower economic cost. Multiple simpler robots are usually a better and more affordable

option than one powerful and expensive robot, essentially for research projects.

Ease of development. Having multiple agents allow developers to focus more pre-

cisely than when trying to have one almighty agent. This is helpful when the task is

as complex as disaster response.

Distributed sensing and action. This feature allows for better and faster reconnais-

sance while being more flexible and adaptable to the current situation.

Inherent parallelism. The use of multiple robots at the same time will inherently search

and cover faster than a single unit.

So, the essential motivation for developing this dissertation resides in the possibilities

and capabilities that a MRS can have for disaster response and recovery. As referred, there are

plenty of applications for rescue robotics and the complexity of USAR demands for multiple

robots. This multiplicity promises an improved performance in sensing and action that are

crucial in a disaster race against time. Also, it provides a way for speeding up operations

by addressing diverse tasks at the same time. Finally, it represents an opportunity for instant

deployment and for increasing the number of first responders in the critical 72 golden hours,

which are essential for increasing the survival rate and for preventing a larger damage.

Additionally, before getting into the specific problem statement, it is worth to refer that

choosing the option for multiple robots keeps developments herein aligned with international

state of the art trends as shown in Figure 1.3. Finally, this topic provides us with an insight

into social, life and cognitive sciences, which, in the end, are all about us.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-23-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 6

Figure 1.3: 70 years for autonomous control levels. Edited from [44].

1.2 Problem Statement and Context

The purpose of this section is to narrow the research field into the specific problematic we

are dealing with. In order to do that, it is important to give a precise context on disasters and

hazards and about mobile robotics. Then we will be able to present an overview of search and

rescue robotics (SAR or simply rescue robotics) for finally stating the problem we address

herein.

1.2.1 Disaster Response

Everyday people around the world confront experiences that cause death, injuries, destroy per-

sonal belongings and interrupt daily activities. These incidents are known as accidents, crises,

emergencies, disasters, or catastrophes. Particularly, disasters are defined as deadly, destruc-

tive, and disruptive events that occur when hazards interact with human vulnerability [182].

The hazard comes to be the threat such as an earthquake, CBRNE, terrorist attack, among

others previously referred (a complete list of hazards is presented in [182]). This dissertation

focuses on aiding in emergencies and disasters such as Table 1.1 classifies.

Once a disaster has occurred, it changes with time through 4 phases that characterize the

emergency management according to [182, 267] and [204]. In spite of the description pre-

sented below, it is worth to refer that Mitigation and Preparedness are pre-incident activities,

whereas Response and Recover are post-incident. Particularly, disaster and emergency re-

sponse requires the capabilities of being as fast as possible for rescuing survivors and avoiding

any further damage, while being cautious and delicate enough to prevent any additional risk.

This dissertation is settled precisely in this phase, where the first responders’ post-incident

actions reside. The description of the 4 phases is now presented.

Ph. 1: Mitigation. Refers to disaster prevention and loss reduction.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-24-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 7

Ph. 2: Preparedness. Efforts to increase readiness for a disaster.

Ph. 3: Response (Rescue). Actions immediately after the disaster for protecting lives and

property.

Ph. 4: Recovery. Actions to restore the basic infrastructure of the community or, preferably,

improved communities.

Table 1.1: Comparison of event magnitude. Edited from [182].

Accidents Crises Emergencies/ Calamities/ Catas-

Disasters trophes

Injuries few many scores hundreds/thousands

Deaths few many scores hundreds/thousands

Damage minor moderate major severe

Disruption minor moderate major severe

Geographic localized disperse disperse/diffuse disperse/diffuse

Impact

Availability abundant sufficient limited scarce

of Resources

Number of few many hundreds hundreds/thousands

Responders

Recovery minutes/ days/weeks months/years years/decades

Time hours/days

During the response phase search and rescue operations take place. In general, these

operations consist on activities such as looking for lost individuals, locating and diagnosing

victims, freeing extricated persons, providing first aids and basic medical care, and transport-

ing the victims away from the dangers. The human operational procedure that persists among

different disasters is described by D. McEntire in [182] as the following steps:

1) Gather the facts. Noticing just what happened, the estimated number of victims and

rescuers, type and age of constructions, potential environmental influence, presence of

other hazards or any detail for improving situational awareness.

2) Asses damage. Determine the structural damage in order to define the best actions basi-

cally including: entering with medical operation teams, evacuating and freeing victims,

or securing the perimeter.

3) Identify and acquire resources. Includes the need for goods, personnel, tools, equip-

ment and technology.

4) Establish rescue priorities. Determining the urgency of the situations for defining which

rescues must be done before others.

5) Develop a rescue plan. Who will enter the zone, how they will enter, which tools are

going to be needed, how they will leave, how to ensure safety for rescuers and victims;

all the necessary for following an strategy.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-25-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 8

6) Conduct disaster and emergency response operations. Search and rescue, cover, fol-

low walls, analyse debris, listen for noises indicating survivors, develop everything that

is considered as useful for saving lives. According to [267], this step is the one that

takes the longest time.

7) Evaluate progress. Prevention of further damage demands for continuously monitor-

ing the situation including to see if the plan is working or there must be a better strategy.

In the described procedure, research has witnessed characteristic human behavior [182].

For example, typically the first volunteers to engage are untrained people. This provokes a

lack of skills that shows people willing to help but unable to handle equipments, coordinate

efforts, or develop any data entry or efficient resources administration and/or distribution. An-

other example is that there are emergent and spontaneous rescuers so that the number can be

overwhelming to manage, therefore causing division of labor and encountered priorities so

that some of them are willing to save relatives, friends and neighbors, without noticing other

possible survivors. Additionally, professional rescuers are not always willing to use volun-

teers in their own operations, thus from time to time, there are huge crowds with just a few

working hands. This situation leads into frustrations that compromise safeness of volunteers,

professional rescue teams, and victims, thus decreasing survival rates while increasing possi-

bilities for larger damages. The only good behavior that persists is that victims do cooperate

with each other and with rescuers during the search and rescue.

Consequently, we can think of volunteering rescue robotic teams for conducting the

search and rescue operations at step 6, which constitutes the most time-consuming disaster

response activities. Robots do not feel emotions such as preferences for relatives, they are

typically built for an specific task, and they will surely not become frustrated. Moreover,

robots have demonstrated to be highly capable for search and coverage, wall following, and

sensing under harsh environments. So, as R. Murphy et al. referred in [204]: there is a

particular need to start using robots in tactical search and rescue, which covers how the field

teams actually find, support, and extract survivors.

1.2.2 Mobile Robotics

Given the very broad definition of robot, it is important to state that we refer to the machine

that has sensors, a processing ability for emulating cognition and interpreting sensors’ signals

(perceive), and actuators in order to enable it to exert forces upon the environment to reach

some kind of locomotion, thus referring a mobile robot. When considering one single mobile

robot, designers must take into account at least an architecture upon which the robotic re-

sources are settled in order to interact with the real world. Then robotic control takes place as

a natural coupling of the hardware and software resources conforming the robotic system that

must develop an specified task. This robotic control has received huge amounts of contribu-

tions from the robotics community most them focusing in at least one of the topics presented

in Figure 1.4: perception and robot sensing (interpretation of the environment), localization

and mapping (representation of the environment), intelligence and planning, and mobility

control.

Furthermore, a good coupling of the blocks in Figure 1.4 shall result in mobile robots ca-

pable to develop tasks with certain autonomy. Bekey defines autonomy in [29] as: a systems’](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-26-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 9

Figure 1.4: Mobile robot control scheme. Image from [255].

capability of operating in the real-world environment without any form of external control

for extended periods of time; they must be able to survive dynamic environments, maintain

their internal structures and processes, use the environment to locate and obtain materials for

sustenance, and exhibit a variety of behaviors. This means that autonomous systems must

perform some task while, within limits, being able to adapt to environment’s dynamics. In

this dissertation special efforts towards autonomy including every block represented in Figure

1.4 are required.

Moreover, when considering multiple mobile robots there are additional factors that in-

tervene for having a successful autonomous system. First of all, the main intention of using

multiple entities is to have some kind of cooperation, thus it is important to define cooperative

behavior. Cao et al. in [63] refer that: “given some task specified by a designer a multiple-

robot system displays cooperative behavior if due to some underlying mechanism, there is an

increase in the total utility of the system”. So, pursuing this increase in utility (better perfor-

mance) cooperative robotics addresses major research axes [63] and coordination aspects [99]

presented below.

Group Architecture. This is the basic element of a multi-robot system, it is the persis-

tent structure allowing for variations at team composition such as the number of robots,

the level of autonomy, the levels of heterogeneity and homogeneity between them, and

the physical constraints. Similar to individual robot architectures, it refers to the set

of principles organizing the control system (collective behaviors) and determining its

capabilities, limitations and interactions (sensing, reasoning, communication and act-

ing constraints). Key features of a group architecture for mobile robots are: multi-level

control, centralization / decentralization, entities differentiation, communications, and

the ability to model other agents.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-27-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 11

• Simple debugging and prototyping.

• Support for parallelism.

• Support for modularity.

• Use of standardized tools.

These characteristics are fully considered in the implementations concerning this dis-

sertation and are detailed further in this document. What is more, the architectural design

involves the need for a coordination and cooperation mechanism for confronting the disaster

response requirements. This implies not only solving individual robot control problems but

also the resource conflicts and navigational problems that arise. For this means information

on robotic control is included.

Mobile Robots Control and Autonomy

A typical issue when defining robotic control is to find where it fits among robotic software.

According to [29] there are two basic perspectives: 1) Some designers refer exclusively to

robot motion control including maintaining velocities and accelerations at a given set point,

and orientation according to certain path. Also, they consider a “low-level” control for which

the key is to ensure steady-states, quick response time and other control theory aspects. 2) On

the other hand, other designers consider robotic control to the ability of the robot to follow

directions towards a goal. This means that planning a path to follow resides in a way of “high-

level” control that constantly sends the commands or directions to the robot control in order

to reach a defined goal. So, it turns difficult to find a clear division between each perspective.

Fortunately, a general definition for robotic control states that: “it is the process of

taking information about the environment, through the robot’s sensors, processing it as nec-

essary in order to make decisions about how to act, and then executing those actions in the

environment”– Matari´ [177]. Thus, robotic control typically requires the integration of mul-

c

tiple disciplines such as biology, control theory, kinematics, dynamics, computer engineering,

and even psychology, organization theory and economics. So, this integration implies the

need for multiple levels of control supporting the idea of the necessity for the individual and

group architectures.

Accordingly, from the two perspectives and the definition, we can refer that robotic

control happens essentially at two major levels for which we can embrace the concepts of

platform control and activity control provided by R. Murphy in [204]. The first one is the one

that moves the robot fluidly and efficiently through any given environment by changing (and

maintaining) kinematic variables such as velocity and acceleration. This control is usually

achieved with classic control theory such as PID controllers and thus can be classified as a

low-level control. The next level refers to the navigational control, which main concern is to

keep the robot operational in terms of avoiding collisions and dangerous situations, and to be

able to take the robot from one location to another. This control typically includes additional

problems such as localization and environment representation (mapping). So, generally it

needs to use other control strategies lying under artificial intelligence such as behavior-based

control and probabilistic methods, and thus being classified as a high-level control.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-29-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 12

Consequently, we must clarify that this dissertation supposes that there is already a

robust, working low-level platform control for every robot. So, there is the need for developing

the high-level activity control for each unit and the whole MRS to operate in search and

rescue missions. In that way, this need for the activity control leads us to three major design

issues [159]:

1. It is not clear how a robot control system should be decomposed; meaning particular

problems at intra-robot control (individuals) that differ from inter-robot control (group).

2. The interactions between separate subsystems are not limited to directly visible connect-

ing links; interactions are also mediated via the environment so that emergent behavior

is a possibility.

3. As system complexity grows, the number of potential interactions between the compo-

nents of the system also grows.

Moreover, the control system must address and demonstrate characteristics presented in

Table 1.2. What is important to notice is that coordination of multi-robot teams in dynamic

environments is a very challenging task. Fundamentally, for having a successfully controlled

robotic team, every action performed by each robot during the cooperative operations must

take into account not only the robot’s perceptions but also its properties, the task requirements,

information flow, teammates’ status, and the global and local characteristics of the environ-

ment. Additionally, there must exist a coordination mechanism for synchronizing the actions

of the multiple robots. This mechanism should help in the exchange of necessary informa-

tion for mission accomplishment and task execution, as well as provide the flexibility and

reliability for efficient and robust interoperability.

Furthermore, for fulfilling controller needs, robotics community has been highly con-

cerned in creating standardized frameworks for developing robotic software. Since they are

significant for this dissertation, information on them is included in Appendix B, particularly

focusing in Service-Oriented Robotics (SOR). Robotic control as well as individuals and

group architectures must consider the service-oriented approach as a way of promoting its

importance and reusability capabilities. In this way, software development concerning this

dissertation turns to be capable of being implemented among different resources and circum-

stances and thus becoming a more interesting, relevant and portable solution with a better

impact.

1.2.3 Search and Rescue Robotics

Having explained briefs on disasters and mobile robots, it is appropriate to merge both re-

search fields and refer about robotics intended for disaster response. In spite of all the pre-

viously referred possibilities for robotics in search and rescue operations, this technology is

new and its acceptance as well as its hardware and software completeness will take time. Ac-

cording to [204], as of 2006, rescue robotics took place only in four major disasters: World

Trade Center, and hurricanes Katrina, Rita and Wilma. Also, in 2011, in the nuclear disaster

at Fukushima, Japan, robots were barely used because of problems such as mobility in harsh

environments where debris is scattered all over with tangled steel beams and collapsed struc-

tures, difficulties in communication because of thick concrete walls and lots of metal, and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-30-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 13

Table 1.2: Important concepts and characteristics on the control of multi-robot systems. Based

on [53, 11, 2, 24].

Situatedness The robots are entities situated and surrounded by the real world. They

do not operate upon abstract representations.

Embodiment Each robot has a physical presence (a body). This has consequences in

its dynamic interactions with the world.

Reactivity The robots must take into account events with time bounds compatible

with the correct and efficient achievement of their goals.

Coherence Referring that robots should appear to an observer to have coherence of

actions towards goals.

Relevance / The active behavior should be relevant to the local situation residing on

Locality the robot’s sensors.

Adequacy / The behavior selection mechanism must go towards the mission accom-

Consistency plishment guided by their tasks’ objectives.

Representation The world aspect should be shared between behaviors and also trigger

for new behaviors.

Emergence Given a group of behaviors there is an inherent global behavior with

group and individual’s implications.

Synthesis To automatically derive a program for mission accomplishing.

Communication Increase performance by explicit information sharing.

Cooperation Proposing that robots should achieve more by operating together.

Interference Creation of protocols for avoiding unnecessary redundancies.

Density N number of robots should be able to do in 1 unit of time, what 1 robot

should in N units of time.

Individuality Interchangeability results in robustness because of repeatability or un-

necessary robots operating.

Learning / Automate the acquisition of new behaviors and the tuning and modifi-

Adaptability cation of existing ones according to the current situation.

Robustness The control should be able to exploit the redundancy of the processing

functions. This implies to be decentralized to some extent.

Programmability A useful robotic system should be able to achieve multiple tasks de-

scribed at an abstract level. Its functions should be easily combined

according to the task to be executed.

Extendibility Integration of new functions and definition of new tasks should be easy.

Scalability The approach should easily scale to any number of robots.

Flexibility The behaviors should be flexible to support many social patterns.

Reliability The robot can act correctly in any given situation over time.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-31-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 14

physical presence within adverse environments because radiation affects electronics [227].

In short, the typical difficulty of sending robots inside major disasters is the need for a big

and slow robot that can overcome the referred challenges [217]. Not to mention the need

for robots capable of performing specific complex tasks like opening and closing doors and

valves, manipulating fire fighting hoses, or even carefully handling rubble to find survivors.

It is worth to mention that there are many types of robots proposed for search and rescue,

including robots that can withstand radiation and fire-fighter robots that shoot water to build-

ings, but the thing is that there is still not one all-mighty unit. For that reason, most typical

rescue robotics implementations in the United States and Japan reside in local incidents such

as urban fires, and search with unmanned vehicles (UxVs). In fact, most of the real implemen-

tations used robotics only as the eyes of the rescue teams in order to gather more information

from the environment as well as to monitor its conditions in order for better decision making.

And even that way, all the real operations allowed only for teleoperated robots and no auton-

omy at all [204]. Nevertheless, these real implementations are the ones responsible of having

a better understanding of the sensing and acting requirements as well as listing the possible

applications for robots in a search and rescue operation.

On the other hand, making use of the typical USAR scenarios where rescue robotics

research is implemented there are the contributions within the IEEE SSRR society and the

RoboCup Rescue. Main tasks include mobility and autonomy (act), search for victims and

hazards (sense), and simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) (reason). Also, human-

robot interactions have been deeply explored. The simulated software version of the RoboCup

Rescue has shown interesting contributions in exploration, mapping and victim detection al-

gorithms. Good sources describing some of these contributions can be found at [20, 19]. The

real testbed version has not only validated functionality of previously simulated contributions,

but also pushed the design of unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) that show complex abilities

for mobility and autonomy. Also, it has leveraged the better usage of proprioceptive instru-

mentation for localization as well as exteroceptive instrumentation for mapping and victims

and hazards detection. Good examples of these contributions can be found at [224, 261].

So, even though the referred RoboCup contributions are simulated solutions far from

reaching a real disaster response operation, they are pushing the idea of having UGVs that can

enable rescuers to find victims faster as well as identifying possibilities for secondary damage.

Also, they are leveraging the possibility for other unmanned vehicles such as larger UGVs

that can be able to remove rubble faster than humans do, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs)

to extend the senses of the responders by providing a birds eye view of the situation, and

unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) and unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) for similarly

extending and enhancing the rescuers’ senses [204].

In summary, some researchers are encouraging the development of practical technolo-

gies such as design of rescue robots, intelligent sensors, information equipment, and human

interfaces for assisting in urban search and rescue missions, particularly victim search, infor-

mation gathering, and communications [267]. Some other researchers are leveraging devel-

opments such as processing systems for monitoring and teleoperating multiple robots [108],

and creating expert systems on simple triage and rapid medical treatment of victims [80].

And there are few others intending the analysis and design of real USAR robot teams for

the RoboCup [261, 8], fire-fighting [206, 98], damaged building inspection [141], mine res-

cue [201], underwater exploration robots [203], and unmanned aerial systems for after-collapse](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-32-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 15

inspection [228]; but they are still in a premature phase not fully implemented and with no

autonomy at all. So, we can synthesize that researchers are addressing rescue robotics chal-

lenges in the following order of priority: mobility, teleoperation and wireless communica-

tions, human-robot interaction, and robotic cooperation [268]; and we can also refer that the

fundamental work is being leaded mainly by Robin Murphy, Satoshi Tadokoro, Andreas Birk,

among others (refer Chapter 2 for full details).

The truth is that there are a lot of open issues and fundamental problems in this barely

explored and challenging research field of rescue robotics. There is an explicit need for robots

helping to quickly locate, assess and even extricate victims who cannot be reached; and there

is an urgency for extending the rescuers’ ability to see and act in order to improve disaster

response operations, reduce risks of secondary damage, and even raise survival rates. Also,

there is an important number of robotics researchers around the globe focusing on particular

problems in the area, but there seems to be no direct (maybe less) effort towards generating

a collaborative rescue multi-robot system, which appears to be further in the future. In fact,

the RoboCup Rescue estimates a fully autonomous collaborative rescue robotic team by 2050,

which sounds pretty much as a reasonable timeline.

1.2.4 Problem Description

At this point we have presented several possibilities and problems that involve robotics for

disaster and emergency response. We have mentioned that robots come to fit well as rescuer

units for conducting search and rescue operations but several needs must be met. First we

defined the need for crafting an appropriate architecture for the individual robots as well as

for the complete multi-robot team. Next we added the necessity for appropriate robotic control

and the efficient coordination of units in order to take advantage of the inherent characteristics

of a MRS and be able to provide efficient and robust interoperability in dynamic environments.

Then we included the requirement for software design under the service-oriented paradigm.

Finally, we expressed that there is indeed a good number of relevant contributions using single

robots for search and rescue but that is not the case when using multiple robots. Thus, in

general the central problem this dissertation addresses is the following:

H OW DO WE COORDINATE AND CONTROL MULTIPLE ROBOTS SO AS TO ACHIEVE

COOPERATIVE BEHAVIOR FOR ASSISTING IN DISASTER AND EMERGENCY RE -

SPONSE , SPECIFICALLY, IN URBAN SEARCH AND RESCUE OPERATIONS ?

It has to be clear that this problem implies the use of multiple robotic agents working

together in a highly uncertain and dynamic environment where there are the special needs for

quick convergence, robustness, intelligence and efficiency. Also, even though the essential

purpose is to address navigational issues, other factors include: time, physical environmen-

tal conditions, communications management, security management, resources management,

logistics management, information management, strategy, and adaptivity [83]. So, we can

generalize by mentioning that the rescue robotic team must be prepared for navigating in

hostile dynamic environment where the time is critical, the sensitivity and multi-agent coop-

eration are crucial, and finally, strategy is vital to scope the efforts towards supporting human

rescuers to achieve faster and more secure USAR operations.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-33-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 16

1.3 Research Questions and Objectives

Having stated problem, the general idea of having a MRS for efficiently assisting human first

responders in a disaster scenario includes several objectives to complete. In Robin Murphy’s

words the most pressing challenges for rescue robotics reside in:

“How to reduce mission times ? How to localize, map, and integrate data from the

robots into the larger geographic information systems used by strategic decision

makers? How to make rescue robot operations more efficient in order to find more

survivors or provide more timely information to responders? How to improve the

overall reliability of rescue robots?”

– Robin. R. Murphy [204]

Consequently, we can state the following research questions addressed herein:

1. H OW TO FORMULATE , DESCRIBE , DECOMPOSE AND ALLOCATE USAR MISSIONS

AMONG A MRS SO AS TO ACHIEVE FASTER COMPLETION ?

2. H OW TO PROVIDE APPROPRIATE COMMUNICATION , INTERACTION , AND CONFLICT

RECOGNITION AND RECONCILIATION BETWEEN THE MRS SO AS TO ACHIEVE EF -

FICIENT INTEROPERABILITY IN USAR?

3. H OW TO ENSURE ROBUSTNESS FOR USAR MISSION ACCOMPLISHMENT WITH CUR -

RENT TECHNOLOGY WHICH IS BETTER FOR SIMPLE BUT FAST CONTROL ?

4. H OW TO MEASURE PERFORMANCE IN USAR SO AS TO LEARN AND ADAPT ROBOTIC

BEHAVIORS ?

5. H OW TO MAKE THE WHOLE SYSTEM EXTENDIBLE , SCALABLE , ROBUST AND RELI -

ABLE ?

In such way, we can define the following objectives in order to develop an answer to the

stated questions:

1. Modularize search and rescue missions.

(a) Identify main USAR requirements.

(b) Decompose USAR operations in fundamental tasks or subjects so as to allocate

them among robots.

(c) Define robotic basic requirements for USAR.

2. Determine the basic structure for the multi-agent robotic system.

(a) Control architecture for the autonomous mobile robots.

(b) Control architecture for the rescue team.

3. Create a distributed system structure for coordination and control of a MRS for USAR.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-34-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 17

(a) Identify possibilities for defining roles in accordance to fundamental tasks in USAR.

(b) Define appropriate robotic behaviors needed for the tasks and matching the defined

roles.

(c) Decompose behaviors into observable disjoint actions.

4. Develop innovative algorithms and computational models for mobile robots coordina-

tion and cooperation towards USAR operations.

(a) Create the mechanism for synchronization of the MRS actions in order to go co-

herently and efficiently towards mission accomplishment.

(b) Create the robotic behaviors for USAR.

(c) Create the mechanism for coordinating behavioral outputs in individual robots

(connect the actions).

(d) Identify the possibilities for an adaptivity feature so as to learn additional behav-

iors and increase performance.

5. Demonstrate results.

(a) Make use of standardized tools for developing the robotic software for both simu-

lation and real implementations.

(b) Implement experiments with real robots and testbed scenarios.

So, next section provides an overview about how we fulfill such objectives so as to push

forward rescue robotics state of the art.

1.4 Solution Overview

Perhaps the most important thing when working towards a long term goal is to provide solu-

tions with certain capabilities for continuity in order to achieve increasing development and

suitability for future technologies. In this way, solutions provided herein intend to promote a

modular development in order for fully integrating and adding new control elements as well as

new software and hardware resources so as to permit upgrades. The main purpose is to have

a solution that can be constantly improved according to the current rescue robotics advances

so that performance and efficiency can be increased. So, in this section, general information

characterizing our solution approach is presented. First is described the behavioral and coor-

dination strategies, then the architectural and service-oriented design, and finally briefs on the

typical testbeds for research experiments.

1.4.1 Dynamic Roles + Behavior-based Robotics

When considering human cognition M. Minsky states in The Emotion Machine [188] that the

human mind has many different ways of thinking that are used according to different circum-

stances. He considers emotions, intuitions and feelings as these different ways of thinking,

which he calls selectors. In Figure 1.5 is exposed how given a set of resources it depends on](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dtc-phd-thesis-finalversion-121215102213-phpapp01/75/PhD-Thesis-Coordination-of-Multiple-Robotic-Agents-for-Disaster-and-Emergency-Response-35-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 18

the active selectors which resources are used. It can be appreciated that some resources can

be shared among multiple selectors.

Figure 1.5: Minsky’s interpretation of behaviors. Image from [188].

In robotics, these selectors come to be the frontiers for sets of actions that activate robotic

resources according to different circumstances (perceptions). This approach was introduced

by R. Brooks in a now-classic paper that suggests a control composition in terms of robotic

behaviors [49]. This control strategy revolutionized the area of artificial intelligence by essen-

tially characterizing a close coupling between perception and action, without an intermediate

cognitive layer. Thus, a classification aroused of what is now known as classic and new arti-

ficial intelligence, refer to Figure 1.6. The major motivation for using this new AI resides in