Optical Switchingnetworking And Computing For Multimedia Systems 1st Mohsen Guizani

Optical Switchingnetworking And Computing For Multimedia Systems 1st Mohsen Guizani

Optical Switchingnetworking And Computing For Multimedia Systems 1st Mohsen Guizani

![survivability, bandwidth provisioning, and performance monitoring, supported at

the optical layer.

Harnessing the newly available bandwidth is difficult because today’s core

network architecture, and the networking equipment it is built on, lack both the

scale and functionality necessary to deliver the large amounts of bandwidth re-

quired in the form of ubiquitous, rapidly scalable, multigigabit services. Today’s

core network architecture model has four layers: IP and other content-bearing

traffic, over ATM for traffic engineering, over SONET for transport, and over

WDM for fiber capacity. This approach has functional overlap among its layers,

contains outdated functionality, and will not be able to scale to meet the exploding

volume of future data traffic, which makes it ineffective as the envisioned archi-

tecture for a next-generation data-centric networking paradigm.

A simplified two-tiered architecture that requires two types of subsystems

will set the stage for a truly optical Internet: service delivery platforms that en-

force service policies, and transport platforms that intelligently deliver the neces-

sary bandwidth to these service platforms. If IP can be mapped directly onto the

WDM layer, some of the unnecessary network layers can be eliminated, opening

up new possibilities for the potential of collapsing today’s vertically layered net-

work architecture into a horizontal model where all network elements work as

peers dynamically to establish optical paths through the network.

High-performance routers (IP layer) plus an intelligent optical transport

layer (DWDM layer) equipped with a new breed of photonic networking equip-

ment hold the keys to the two pieces of the puzzle that will compose the optical

Internet. Closer and efficient interworking of these two pieces is the key to solving

the puzzle. Specifically, linking the routing decision at the IP layer with the point-

and-click provisioning capabilities of optical switches at the transport layer, in

our opinion, is the cornerstone to the puzzle’s solution. This will allow routers

and ATM switches to request bandwidth where and when they need it.

Now that the basic building blocks are available for building such a network

of networks, the key innovations will come from adding intelligence that enables

the interworking of all the network elements (routers, ATM switches, DWDM

transmission systems and OXCs). The IETF has already addressed the interwork-

ing of routers and optical switches through the multiprotocol lambda switching

(MPλS) initiative [1]. The main goal of this initiative is to provide a framework

for real-time provisioning of optical channels, through combining recent ad-

vances in multiprotocol label switching (MPLS) traffic-engineering control plane

with emerging optical switching technology in a hybrid IP-centric optical net-

work. However, only a high-level discussion has been presented.

This work presents a balanced view of the vision of the next generation

optical Internet and describe, two practical near-term optical Internet candidate

model architectures along with a high-level discussion of their relative advantages

Copyright 2002 by Marcel Dekker. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-26-320.jpg)

![and disadvantages: (1) a router-centric architecture deployed on a thin optical

layer, and (2) a hybrid router/OXC-centric architecture deployed on a rich and

intelligent optical transport layer. A router-centric model assumes that IP-based

traffic is driving all the growth in the network, and the most cost-effective solution

is to terminate all optical links directly on the router. The granularity at which

data can be switched is at the packet level. In a hybrid router/OXC model, all

optical links coming into a core node are terminated on an OXC. The cross-

connect switches transit traffic (data destined for another core node) directly to

outbound connections, while switching access traffic (data destined for this core

node) to ports connected to an access router. The granularity at which data can

be switched is at the entire wavelength level, e.g., OC-48 or OC-192.

Both models are based on the two-layer model, IP directly over WDM,

and therefore DWDM equipment is available to provide the underlying band-

width. The main issue is really about the efficiency of a pure packet-switched

network versus a hybrid, which packet switches only at the access point and

circuit switches through the network. The distinction between these two models

is based on the way that the routing and signaling protocols are run over the IP

and the optical subnetwork layers.

A special consideration will be given to the hybrid router/OXC-centric

model, referred to as the integrated model in a recent IETF draft [2], since it is

our opinion that this model represents a credible starting point toward achieving

an all-optical Internet. This model aims at a tighter and more coordinated integra-

tion between the IP layer and the underlying DWDM-based optical transport

layer.

The work presented here builds on the recent IETF initiatives [1,2] and

other related work on the (MPλS) [3,4] and addresses the implementation issues

of the path selection component of the traffic engineering problem in a hybrid

IP-centric DWDM-based optical network. An overview of the methodologies and

associated algorithms for dynamic lightpath computation, that is based on a fully

distributed implementation, is presented. Specifically, we show how the complex

problem of real-time provisioning of optical channels can be simplified by using

a simple dynamic constraint-based routing and wavelength assignment (RWA)

algorithm that computes solutions to three subproblems: the routing problem, the

constrained-based shortest route selection problem, and the wavelength assign-

ment problem.

We present two different schemes for dynamic provisioning of the optical

channels. The first scheme is conceptually simple, but the overhead involved is

excessive. The second scheme is not as overhead consuming as the first one but

has the drawback that the chosen wavelength is only locally optimized along the

selected route; consequently the utilization of network resources is not globally

optimized. Two different scenarios are then considered: provisioning lightpaths

Copyright 2002 by Marcel Dekker. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-27-320.jpg)

![be less than optimal) or continue to be delivered over a parallel ATM network.

We will refer to this data-centric networking solution as a router-centric architec-

ture. The details of this architecture will be considered in the next section.

On the other hand, if data services are treated as one of many competing

services in a portfolio of service types, then it seems appropriate to build a net-

work that is optimized to carry a mix of different service types rather than being

optimized for one specific service type. We will refer to this networking solution

as a hybrid router/OXC-centric architecture, the details of which will also be

considered in the next section.

2.2 The Envisioned Data-Centric Networking Paradigm:

Optical Internet

Recently there have been several initiatives in building an optical Internet where

IP routes are interconnected directly with WDM links [5]. A simplified two-tiered

architecture that require two types of subsystems will set the stage for a truly

optical Internet: service delivery platforms that enforce service policies and trans-

port platforms that intelligently deliver the necessary bandwidth to these service

platforms. High-performance routers plus an intelligent optical transport layer

equipped with a new breed of photonic networking equipment hold the keys to

the two pieces of the puzzle that will compose the optical Internet.

However, closer and efficient interworking of these two pieces is the key

to solving the puzzle. Specifically, linking the routing decision at the IP layer

with the point-and-click provisioning capabilities of optical switches at the trans-

port layer, in our opinion, is the cornerstone to the puzzle’s solution. This will

allow routers and ATM switches to request bandwidth where and when they need

it.

As high-performance routers emerge with high bit rate optical interfaces

(like OC-48c and OC-192c), the high bit rate multiplexing traditionally per-

formed by a SONET terminal is no longer necessary. These routers, which repre-

sent the first piece of the two-tiered networking model, can also handle equipment

protection, further diminishing the need for SONET. On the other hand, in order

for this new two-tiered model to be truly viable, optical networking technologies

and systems must support additional functionality, including multiplexing, rout-

ing, switching, survivability, bandwidth provisioning, and performance monitor-

ing. These emerging sets of optical networking functionality and equipment is

the second piece of the two-tiered puzzle that will compose the optical Internet.

The following are some of the salient features and associated dramatic tech-

nological changes that should take place en route towards implementing the envi-

sioned optical Internet: (1) SONET transport should give way to optical transport;

fast restoration (50 ms) is necessary; without it, a significant availability and

reliability benchmark set by SONET would be lost; (2) bandwidth is provisioned,

Copyright 2002 by Marcel Dekker. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-29-320.jpg)

![channel provisioning driven by IP data paths and traffic engineering mechanisms.

This will require a tight cooperation of routing and resource management proto-

cols at the two layers. Multiprotocol label switching (MPLS) for IP packets is

believed to be the best integrating structure between IP and WDM. MPLS brings

two main advantages. First, it can be used as a powerful instrument for traffic

engineering. Second, it fits naturally to WDM when wavelengths are used as

labels. This extension of the MPLS is called multiprotocol lambda switching [1–

4]. The main characteristics of this model is that the IP/MPLS layers act as peers

of the optical transport network, so that a single routing protocol instance runs

over both the IP/MPLS and optical domains.

Hybrid advocates argue that routing is expensive and should be used only

for access, because circuit switching is better for asynchronous traffic, and restor-

ing traffic at the optical layer is faster and well understood. In addition, this model

allows seamless interconnection of IP and optical networks. The downside to this

approach is that hybrid networks have the disadvantages inherent to a circuit

switch model—they waste bandwidth and introduce an N2

problem, e.g., to con-

nect 30 routers in the east with 30 routers in the west requires more than 900

connections. Another disadvantage of the hybrid approach is that it requires rout-

ing information specific to optical networks to be known to routers. Finally, as

it is assumed they will need a router, hybrid solutions include another device to

manage.

In the following subsections, we start off with an overview of MPLS. The

architecture of the hybrid router/OXC-centric model considered here is then pre-

sented. Finally, we consider the implementation issues of the dynamic path selec-

tion component of the traffic engineering problem in the hybrid router/OXC-

centric model.

3.3.1 Overview of MPLS

MPLS introduces a new forwarding paradigm for IP networks. The idea is similar

to that in ATM and frame relay networks. A path is first established using a

signaling protocol; then a label in the packet header, rather than the IP destination

address, is used for making forwarding decisions in the network. In this way,

MPLS introduces the notion of connection-oriented forwarding in an IP network.

In the absence of MPLS, providing even the simplest traffic engineering functions

(e.g., explicit routing) in an IP network is very cumbersome.

Two signaling protocols may be used for path setup in MPLS: the

Constraint-Based Routed Label Distribution Protocol (CR-LDP) and extensions

to Resource Reservation Protocol (RSVP) [6]. The path set up by the signaling

protocol is called a label-switched path (LSP). Routers that support MPLS are

called label-switched routers (LSRs). An LSP typically originates at an edge LSR,

traverses one or more core LSRs, and then terminates at another edge LSR. The

Copyright 2002 by Marcel Dekker. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-33-320.jpg)

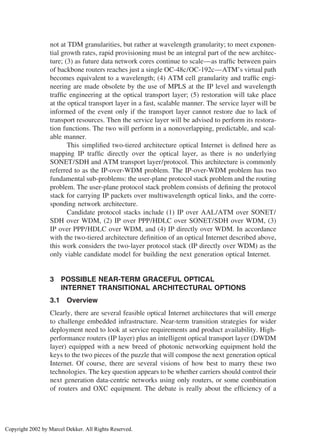

![OC-192) from input ports to output ports. The switching fabric may be purely

optical or electrical or a combination. The LSRs are clients of the optical network

and are connected to their peers over switched optical paths (lightpaths) spanning

potentially multiple OXCs. LSRs process traffic in the electrical domain on a

packet-by-packet basis. The OXC processing unit is one wavelength.

A lightpath is a fixed bandwidth connection between two network elements

such as IP/LSR routers established via the OXCs. Two IP/LSR routers are logi-

cally connected to each other by a single-hop channel. This logical channel is

the so-called lightpath. A continuous lightpath is a path that uses the same wave-

length on all links along the whole route from source to destination.

Each node in this network consists of an IP router and a dynamically recon-

figurable OXC. The IP/LSR router includes software for monitoring packet flows.

The router is responsible for all nonlocal management functions, including the

management of optical resources, configuration and capacity management, ad-

dressing, routing, topology discovery, traffic engineering, and restoration. In gen-

eral, the router may be traffic bearing, or it may function purely as a controller

for the optical layer and carry no IP data traffic [2]. In this work, it is assumed

to be a combination of both. The node may be implemented using a stand-alone

router interfacing with the OXC through a defined interface, or it may be an

integrated system, in which the router is part of the OXC system.

These OXCs may be equipped with full wavelength conversion capability,

limited wavelength conversion capability, or no wavelength conversion capability

at all. If the WDM systems contain transponders or if electronic OXCs are used,

then it is implied that a channel associated with a specific wavelength in the

WDM input can be converted to an output channel associated with a different

wavelength in the WDM output (i.e., wavelength conversion is inherent). How-

ever, if the switching fabric is optical and there is no transponder function in the

WDM system, then wavelength conversion is only implemented if optical-to-

electronic conversion is performed at the input or output ports, or if optical wave-

length converters are introduced to the OXC.

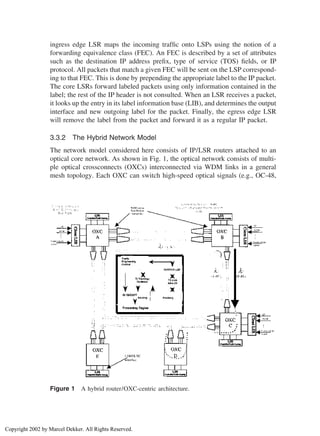

Some of the processing capabilities and functionality of the hybrid nodes

(wavelength conversion capable or incapable) comprising the core network are

shown in Figs. 2, 3, and 4, respectively. These include, but are not limited to,

wavelength merging, flow aggregation (grooming) into a continuous lightpath,

flow switching to a different lightpath, and flow processing/termination at an

intermediate node along a continuous lightpath. Wavelength merging is a strategy

for reusing precious wavelengths that allows tributary flows to be aggregated by

merging packets from several streams. The OXC requires enhanced capabilities

to perform this merging function [7]. The device would be able to route the same

wavelength from different incoming fibers into a single outgoing fiber. The key

property of this device is that contention between bits on the wavelength must

be resolved before they are multiplexed into the common outgoing fiber.

Copyright 2002 by Marcel Dekker. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-35-320.jpg)

![Figure 4 Backbone nodes with partial wavelength conversion and O-E-O processing

capabilities.

The MPLS label switching concept is extended to include wavelength-

switched lightpaths. Optical nodes are treated as IP-MPLS devices, termed here-

after optical lambda switch router (O-LSR) nodes, where each O-LSR node is

assigned a unique IP address [3]. We assume that the OXCs are within one admin-

istrative domain and run interdomain routing protocols, such as OSPF and IS-

IS, for the purpose of dynamic topology discovery. For optimal use of network

resources, the routing protocols have been enhanced to disseminate additional

link-state information over that currently done by standard OSPF and IS-IS proto-

cols.

The request to set up a path can come either from a router or from an ATM

switch connected to the OXCs (O-LSRs). The request must identify the ingress

and the egress OXCs between whom the lightpath has to be set up. Additionally,

it may also include traffic-related parameters such as bandwidth (OC-48/Oc-192),

reliability parameters and restoration options, and setup and holding priorities

for the path. The lightpaths are provisioned by choosing a route through the

network with sufficient available capacity. The lightpath is established by allocat-

ing capacity on each link along the chosen route, and appropriately configuring

the OXCs. Protection is provided by reserving capacity on routes that are physi-

cally diverse from the primary lightpath.

Copyright 2002 by Marcel Dekker. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-37-320.jpg)

![link-state advertisement protocol, at the first-hop router’s TED. Specifically, these

are the link attributes that are included as part of each router’s link-state advertise-

ment.

As an illustrative example, consider a lightpath request from A to C as

shown in Fig. 1. There are two alternative disjoint routes (k ⫽ 2 in this example)

that should be stored at node A. The first route (first shortest path route) is A–

B–C, and the second route is A–E–D–C. The first route has two links, AB and

BC. Assume that the number of used wavelengths on link AB ⫽ 4, and that the

number of used wavelengths on link BC ⫽ 12. Then the average number of used

wavelengths on route A–B–C ⫽ 8 wavelengths.

The second disjoint alternative route (second shortest path route) has three

links, AE, ED, and DC. Assume that the number of used wavelengths on link

AE ⫽ 5, the number of used wavelengths on link ED ⫽ 2, and that the number

of used wavelengths on link DC ⫽ 8, Then the average number of used wave-

lengths on this route ⫽ 5 wavelengths. Because the average number of used

wavelengths [5] on the second route (A–E–D–C) is less than those [8] on the

first route (A–B–C), the second route is selected. Note that route A–B–C was

not selected, even though it is the shortest path. This is a constraint-based shortest

route selection problem.

4.2.3 The Wavelength Assignment Problem

For a given request, once a constrained shortest path (the path with the least

average number of used wavelengths per the entire route) is selected out of the

k routes, a wavelength assignment algorithm is invoked (on-line) to assign the

appropriate wavelength(s) across the entire route. A wavelength assignment algo-

rithm must thus be used to select the appropriate wavelength (S).

Several heuristics wavelength assignment algorithms can be used, such as

the Random wavelength assignment (R), least used (LU), most used (MU), least-

loaded (LL), and max-sum algorithms [8–12]. The implementation of these algo-

rithms requires the propagation of information throughout the network about the

state of every wavelength on every link in the network. As a result, the state

required and the overhead involved in maintaining this information would be

excessive. However, the advantage gained is that the chosen wavelength is glob-

ally optimized, and consequently the utilization of network resources is globally

optimized, since the wavelength assignment algorithm has global information

about the state of every wavelength on every link in the network.

Note that, as mentioned above, the complexity of the wavelength assign-

ment algorithm depends on whether the network nodes are wavelength conver-

sion capable or incapable. In general, the complexity of the proposed approach

and the overhead involved in maintaining and updating the TED depends on the

value of k. The smaller the value of k, the lower the overhead involved and the

simpler the algorithm. A reasonable value of k may range from 4 to 6.

Copyright 2002 by Marcel Dekker. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-41-320.jpg)

![cantly longer time. The first-hop router is responsible for ensuring that restoration

capacity is reserved for all restorable failures. The first-hop router informs the

source once this is completed. The establishment of a restored lightpath is com-

pleted when the primary capacity is allocated and the restoration capacity is re-

served [2].

4.4 Provisioning Lightpaths in a Network Without

Wavelength Conversion Capabilities

A network or a subnetwork that does not have wavelength converters will be

referred to as being wavelength continuous. In the case where wavelength con-

verters are not available, the procedures used to provision a lightpath in the above

section, where wavelength converters are available, are identical, except that the

wavelength assignment algorithm is now different.

In this case, where wavelength converters are not available, a common

wavelength must be located on each link along the entire route. Whatever wave-

length is chosen on the first link defines the wavelength allocation along the rest

of the section. A wavelength assignment algorithm must thus be used to choose

this wavelength.

Finally, in the case where the lightpath is wavelength continuous (cut-

through), optical nonlinearities, chromatic dispersion, amplifier spontaneous

emission, and other factors together limit the scalability of an all-optical network.

Routing in such networks will then have to take into account noise accumulation

and dispersion to ensure that lightpaths are established with adequate signal quali-

ties. This work assumes that the all-optical (sub-) network considered is geo-

graphically constrained so that all routes will have adequate signal quality, and

physical layer attributes can be ignored during routing and wavelength assign-

ment. However, the policies and mechanisms proposed here can be extended to

account for physical layer characteristics.

It is important to emphasize that while the proposed scheme is conceptually

simple, to provision the network one needs to propagate information throughout

the network about the state of every wavelength on every link in the network.

As a result, the states required and the overhead involved in maintaining this

information would be excessive.

To relieve the excessive overhead problem, another approach is first to

select the shortest path between source and destination based only on the conven-

tional OSPF algorithm; except that the overhead consuming heuristics wave-

length assignment algorithms used above should now be replaced with a simple

wavelength assignment signaling protocol (SWASP) that requires wavelength

usage information from only the links along the chosen route [2,7].

In this case, we must select a route and wavelength upon which to establish

a new lightpath, without detailed knowledge of wavelength availability. Con-

Copyright 2002 by Marcel Dekker. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-43-320.jpg)

![structing the continuous lightpath requires SWASP to pick a common free wave-

length along the flow path; therefore the algorithm must collect the list of free

wavelengths for each node. If there is one free wavelength common to all the

nodes, it will be picked; if not, the algorithm returns a message to the first-hop

router informing it that the lightpath cannot be established. The signaling can be

initiated either at the, end of the path (last-hop router) or at the beginning of the

path (first-hop router) [7].

If the signaling is initiated from the first-hop router, the algorithm picks

the set of free wavelengths along the first link of the path to be established. When

the next hop receives that set it intersects it with its own free wavelength set and

forwards the result to the next hop. If the final set is not empty, the last-hop

router picks one free wavelength from the resulting set, configures its local node,

and sends an acknowledgment back to the previous hop with the chosen wave-

length. Upon receiving an acknowledgment, the previous hop configures its local

node and passes the acknowledgment to its previous hop, until the packet is

received by the first-hop router (ingress node) [7]. The signaling can also be

initiated from the last-hop router, but it will take more time.

Although this second scheme is not as overhead consuming as the first one,

the drawback is that the chosen wavelength is now only locally optimized, and

consequently the utilization of network resources is not globally optimized.

5 CONCLUSION

An overview of the vision of the next generation optical Internet has been pre-

sented. We have described two practical near-term optical Internet candidate

model architectures along with a high-level discussion of their relative advantages

and disadvantages: a router-centric architecture deployed on a thin optical layer,

and a hybrid router/OXC-centric architecture deployed on a rich and intelligent

optical transport layer. The fundamental distinction between these two models

is based on the way that the routing and signaling protocols are run over the IP

and the optical subnetwork layers.

This work has addressed the implementation issues of the path selection

component of the traffic-engineering problem in a hybrid IP-centric DWDM-

based optical network. An overview of the methodologies and associated algo-

rithms for dynamic lightpath computation has also been presented. Specifically,

we have shown how the complex problem of real-time provisioning of optical

channels can be simplified by using a simple dynamic constraint-based routing

and wavelength assignment (RWA) algorithm that computes solutions to three

subproblems: the routing problem, the constraint-based shortest route selection

problem, and the wavelength assignment problem.

We have also presented two different schemes for dynamic provisioning

Copyright 2002 by Marcel Dekker. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-44-320.jpg)

![Figure 1 Various applications depend on the MAC protocols used in shared medium

networks.

A plethora of MAC protocols have been proposed for future-generation

LANs/MANs [4]. Unfortunately, most of these MAC protocols are not suitable

for multimedia applications because they have been designed with one generic

traffic type in mind. As a result, they perform quite well for the traffic types

they have been designed for but poorly for other traffic streams with different

characteristics. This observation is true for MAC protocols for wireline networks

as well as wireless networks.

The objective of this paper is to propose a methodology and framework

for integrating different MAC protocols into a single shared medium network

efficiently to accommodate various types of multimedia traffic streams with dif-

ferent characteristics and QoS demands. The proposed integrated MAC protocol

is termed Multimedia Medium Access Control (Multimedia-MAC) protocol. We

also develop efficient analytical methodologies for the performance evaluation

of our MAC protocols using different traffic and networking environments.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 gives an overview of MAC

protocols. Section 3 introduces our Multimedia-MAC protocol. In Sec. 4, we

derive an analytical model for the performance evaluation of our protocol. We

present an example application of our Multimedia-MAC using wavelength divi-

sion multiplexing networks in Sec. 5. Finally, Sec. 6 concludes the paper.

2 OVERVIEW OF MAC PROTOCOLS

MAC protocols have been the subject of a vast amount of research over the past

two decades. Without going into detail about any specific MAC protocol, we can

Copyright 2002 by Marcel Dekker. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-47-320.jpg)

![classify MAC protocols into three categories [4]: preallocation access protocols,

reservation protocols, and random access protocols.

Preallocation-based protocols. The nodes access the shared medium in a

predetermined way. That is, each active node is allocated one or more

slots within a frame, and these slots cannot be accessed by other nodes.

Reservation-based protocols. A node that is preparing a packet transfer has

to reserve one or more time slots within a frame before the actual packet

transmission can take place. The reservation is typically done using dedi-

cated control slots within a frame or a separate reservation channel. As

a result, access to the data slots is achieved without the possibility of

collision.

Random access protocols. The nodes access the shared medium with no

coordination between them. Thus when more than one packet is transmit-

ted at the same time, a collision occurs, and the information contained

in all the transmitted packets is lost. As a result, a collision resolution

mechanism must be devised to avoid high packet delays or even unstable

operation under high loads.

To serve various multimedia applications, the traffic loaded on the network

is no longer of a single type but is a mixture of different types of traffic streams

to be served simultaneously. Different traffics have different characteristics and

thus have different transmission requirements. We can classify multimedia traffic

streams as a function of their data burstiness and delay requirements as shown

in Fig. 2. For example, video/audio streams and plain old telephone service

(POTS) have small data burstiness but require almost constant transmission delay

and almost fixed bandwidth in order to guarantee their QoS. On the other hand,

applications such as image networking and distance learning are less stringent

in terms of their delay requirements, but their traffic streams are very bursty.

Finally, there are other applications that require a very low delay while their

traffic streams are bursty. Examples of this type of applications include control

messages for video-on-demand systems or interactive games, and network control

and management.

These different traffic streams are better served by different MAC proto-

cols. Video/audio data streams and other constant-bit-rate (CBR) traffic streams

benefit best from allocation-based MAC protocols, since they can guarantee that

each node has a cyclic and fixed available bandwidth. The best MAC protocols

for this purpose would be a simple round-robin time division multiplexing access

(TDMA) scheme. On the other hand, reservation-based MAC protocols are very

well suited for applications where the traffic streams are bursty (i.e., VBR Traffic)

or the traffic load of the nodes is unbalanced, since reservation-based MAC proto-

cols schedule the transmission according to a particular transmission request.

Copyright 2002 by Marcel Dekker. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-48-320.jpg)

![a packet has missed its transmission deadline or not. We propose a general ap-

proach to find the deadline missing rate (DMR), which is defined as the probabil-

ity that a packet transmission exceeds an arbitrary given deadline. This model

can also be used in finding traditional metrics, such as mean packet delay and

throughput. We use a queueing system with a vacation model to model the wait-

ing time distribution of the subprotocols. Then we employ a numerical method

to evaluate the distribution and obtain its moments. Based on the moments, we

approximately determine the DMR of these subprotocols (Fig. 4).

In a Multimedia-MAC protocol, the traffic streams are transmitted under

the control of different subprotocols, and are multiplexed into the shared chan-

nel(s). Thus the services given to each of the data streams are not continuous,

i.e., the service may be unavailable sometimes. As a result, we employ a queueing

with vacation model to model the Multimedia-MAC protocol. Corresponding to

different features of the different traffics and their services, we use a different

queueing model to analyze their performance. More precisely, we use a D/D/1

queue with vacation system to model a TDM subprotocol operation; we use a

M(x)

/M/1 queue with Erlang vacation to model the reservation type protocol; and

we use a M/G/1 queue with deterministic vacation to model the random access

protocol. To determine the DMR of a packet for a given traffic load and deadline,

the packet waiting time distribution should be derived. However, it is a difficult

problem to get the distribution of non-M/M/1 queues with general vacation [3].

Figure 4 Our approach to modeling and analyzing the Multimedia-MAC protocol.

Copyright 2002 by Marcel Dekker. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-52-320.jpg)

![We successfully apply an approach that combines the decomposition properties

of general queueing vacation systems, numerically calculating the moments of

the waiting time distribution from their Laplace–Stieltjes Transform (LST)

forms, and approximately computing the tail probability from the moments.

4.1 General Queueing Model Without Vacation

Let us start from a simple case: a general arrival and a general service with a

single server model, denoted a GI/G/1 queue.

4.1.1 G/G/1 Queue

Let wn denote the waiting time of the nth packet in the queue. Let un denote the

interarrival time between the nth packet and the n ⫹ 1th packet, and vn denote

the service time of the nth packet. We choose the packet departure time as the

embedded point, denoted as Dn. Because we assume there is no server vacation

at the moment, the transmission is continuous if the packet buffer is nonempty,

i.e., the waiting time of a packet is equal to the previous packet waiting time

plus its service time minus the interarrival time between them. Hence we have

wn⫹1 ⫽ wn ⫹ vn ⫺ un (1)

⫽ wn ⫹ xn (2)

where xn ⫽ vn ⫺ un . If the buffer is empty when the n ⫹ 1th packet arrives, the

packet is transmitted immediately without queueing, so wn⫹1 ⫽ 0 in this case.

Combining these two cases, we get

wn⫹1 ⫽ MAX(0,wn ⫹ vn ⫺ un ) (3)

From the above equation, we can get the idle period in which the server (the

channel) is idle. The idle period is denoted by In ⫽ ⫺MIN(0,wn ⫹ vn ⫺ un ).

Then

wn⫹1 ⫺ In ⫽ wn ⫹ xn (4)

E[e⫺s(wn⫹1⫺In

)

] ⫽ E[e⫺swn]E[e⫺sxn] (5)

Because we have wn⫹1 ⫽ 0, when In ⬎ 0, and wn ≠ 0 when In ⫽ 0, we get

E[e⫺s(wn⫹1⫺In

)

] ⫽ E[e⫺swn |In ⬎ 0]Pr(In ⬎ 0)

(6)

⫹ E[e⫺swn⫹1 |In ⫽ 0]Pr(In ⫽ 0)

Because wn⫹1 ⫽ 0 when In ⬎ 0, then E[e⫺swn⫹1 |In ⬎ 0] ⫽ 1. Let Pr(In ⬎ 0) ⫽

a0 which is the probability of a new packet arrival seeing an empty buffer. Using

Eq. (7), we get

Copyright 2002 by Marcel Dekker. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-53-320.jpg)

![E[e⫺swn]E[e⫺sxn] ⫽ E[e⫺s(⫺In) |In ⬎ 0]α0 ⫹ E[e⫺sWn⫹1] ⫺ a0 (7)

In a steady state, we get

lim

n→∞

E[e⫺swn ] ⫽ lim

n→∞

E[e⫺swn⫹1 ] ⫽ E[e⫺sW

]

Using the LST definition, the LST of the waiting time in the queue is W*

(s) ⫽ E[e⫺sW

], and the LST of the idle period I is I* (s) ⫽ E[e⫺sI

]. We define

the LST of the accessory random variable x ⫽ limn→∞ xn to be K* (s) ⫽ E[e⫺sX

].

Then by Eq. (7), we can get the packet waiting time in a G/G/1 queue as

W* (s) ⫽

α0 [1 ⫺ I* (⫺s)]

1 ⫺ K* (s)

(8)

From equation (8), we can derive the LST forms of different queueing models

for different arrivals and service disciplines.

4.1.2 D/D/1 Queue

In a D/D/1 queue, the packet arrival rate and service rate are deterministic. Let

λ denote the arrival rate and µ represent the service rate. Then un ⫽ 1/λ, and vn

⫽ 1/µ. Hence

I* (s) ⫽ e⫺s(1/µ⫺1/λ)

K* (s) ⫽ E[e⫺s(vn⫺un)

] ⫽ e⫺s(1/λ⫺ 1/µ)

Thus the LST form of a D/D/1 queue is W* (s) ⫽ 1.

4.1.3 M/G/1 Queue

For a Poisson arrival system, the idle time distribution is the same as the inter-

arrival-time distribution because of the property of Poisson Arrival See Time

Averages (PASTA) which implies the memoryless property of the Poisson pro-

cess (17). Then

A* (s) ⫽ I* (s) ⫽

λ

(λ ⫹ s)

(9)

where A is the random variable of packet arrivals and A* (s) is its LST. We

denote the packet service time distribution by B(t) and its LST by B* (s). Its

mean is µ ⫽ B*′ (0).

Recall that

K(s) ⫽ E[e⫺s (vn⫺un)

] ⫽ E[e⫺svn]E[e⫺s(⫺un)

] ⫽ B* (s)

λ

λ ⫺ s

(10)

Copyright 2002 by Marcel Dekker. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-54-320.jpg)

![Nadouesiouek is given in a Relation of 1656,

Nadouechiouec, 1660; and soon also

Nadouesseronons, Nadouesserons, etc.

An excellent article on the Sioux, entitled Dakota Land

and Dakota Life, by Rev. E. D. Neill, occupies pp. 254-

294 of the 2d ed. 1872, of Minn. Hist. Soc. Coll.,

originally published in 1853.

[VIII-4] The punctuation of the last two sentences in

the original left Pike's meaning obscure. It was by no

means evident whether the language which he had

used to the Indians held up to their minds a happy

coincidence of circumstances which the traders helped

to bring about before the Almighty interfered at all, or

whether the happy coincidence of circumstances

consisted in the endorsement of his language both by

the traders and the Almighty. On the whole, I am

inclined to think he meant that the speeches he made

to the Indians whom he addressed directly were

repeated and backed up by the traders among those

Indians to whom he had no access; and that this was

the happy coincidence of circumstances which enabled

the Almighty to finish the business. But after all I am

not quite confident that I catch his meaning. If I do, I

must say that he is not very complimentary to the

Deity, whose assistance he suspects may have been

necessary to effect that which the traders and himself

jointly attempted. For it seems from his further

reflections on the subject that he thought God possibly

equal to burying the hatchet between the Sioux and

Chippewas, but hardly able to keep the peace without

the assistance of the military and of a special agent.

However, Pike was nothing if not a good soldier, and

he had Napoleonic authority for supposing that God](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-56-320.jpg)

![would always be found on the side of the heaviest

artillery.

[IX-1] This article formed Doc. No. 2, pp. 52, 53 of the

App. to Part III. of the orig. ed., entitled "Explanatory

Table of Names of Places, Persons, and Things, made

use of in this Volume." But there is not a name of any

person in it, and not a name of anything in it that does

not belong to Part I., i. e., to the Mississippi voyage

alone. Having thus been obviously out of place in Part

III., it is now brought where it belongs, and a new

chapter made for it, with a new head, which more

accurately indicates what it is. But even as a

vocabulary of Mississippian place-names, it is a mere

fragment, neither the plan nor scope of which is

evident, as the names occur neither in alphabetical nor

any other recognizable order, and include only a very

small fraction of those which Pike uses in Part I. of his

book. He may have intended to make something of it

which should justify the title he gave it, and left it out

of Part I. for that reason; but nothing more came of it,

and it was finally bundled into Part III. The lists

include a few terms which do not occur elsewhere in

the work, as for example, "River of Means"; but are

chiefly curious as an evidence of the difficulty our

author found in spelling proper names twice alike.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/488363-250521162021-fd7b383a/85/Optical-Switchingnetworking-And-Computing-For-Multimedia-Systems-1st-Mohsen-Guizani-57-320.jpg)