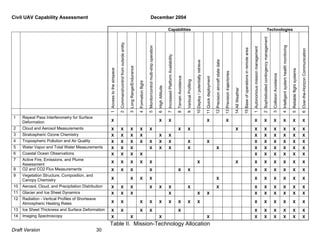

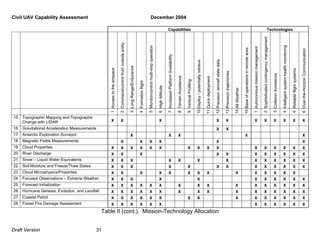

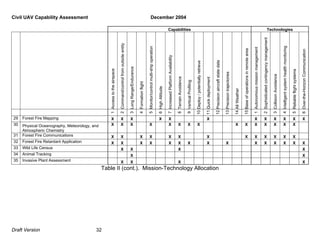

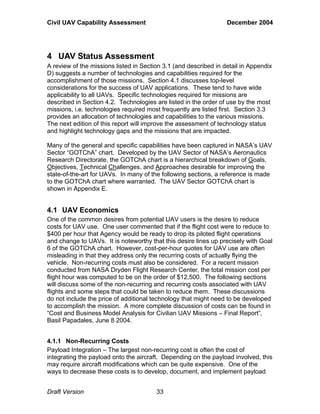

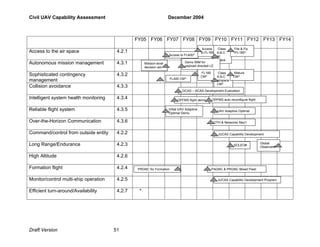

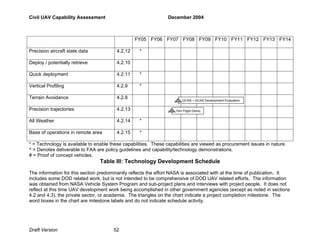

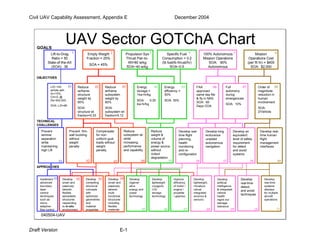

This document provides a draft assessment of civil uninhabited aerial vehicle (UAV) missions and technologies. It identifies 35 potential civil UAV missions across earth science, homeland security, commercial, and land management categories. From these missions, the document determines 21 key capabilities and technologies needed to support the missions, such as access to national airspace, long range/endurance, and over-the-horizon communication. The document also discusses the current state and development status of these capabilities. The goal is to complement the Department of Defense's UAV roadmap and help guide funding to develop enabling technologies for civil UAV missions.