Morphing A Guide To Mathematical Transformations For Architects And Designers Choma

Morphing A Guide To Mathematical Transformations For Architects And Designers Choma

Morphing A Guide To Mathematical Transformations For Architects And Designers Choma

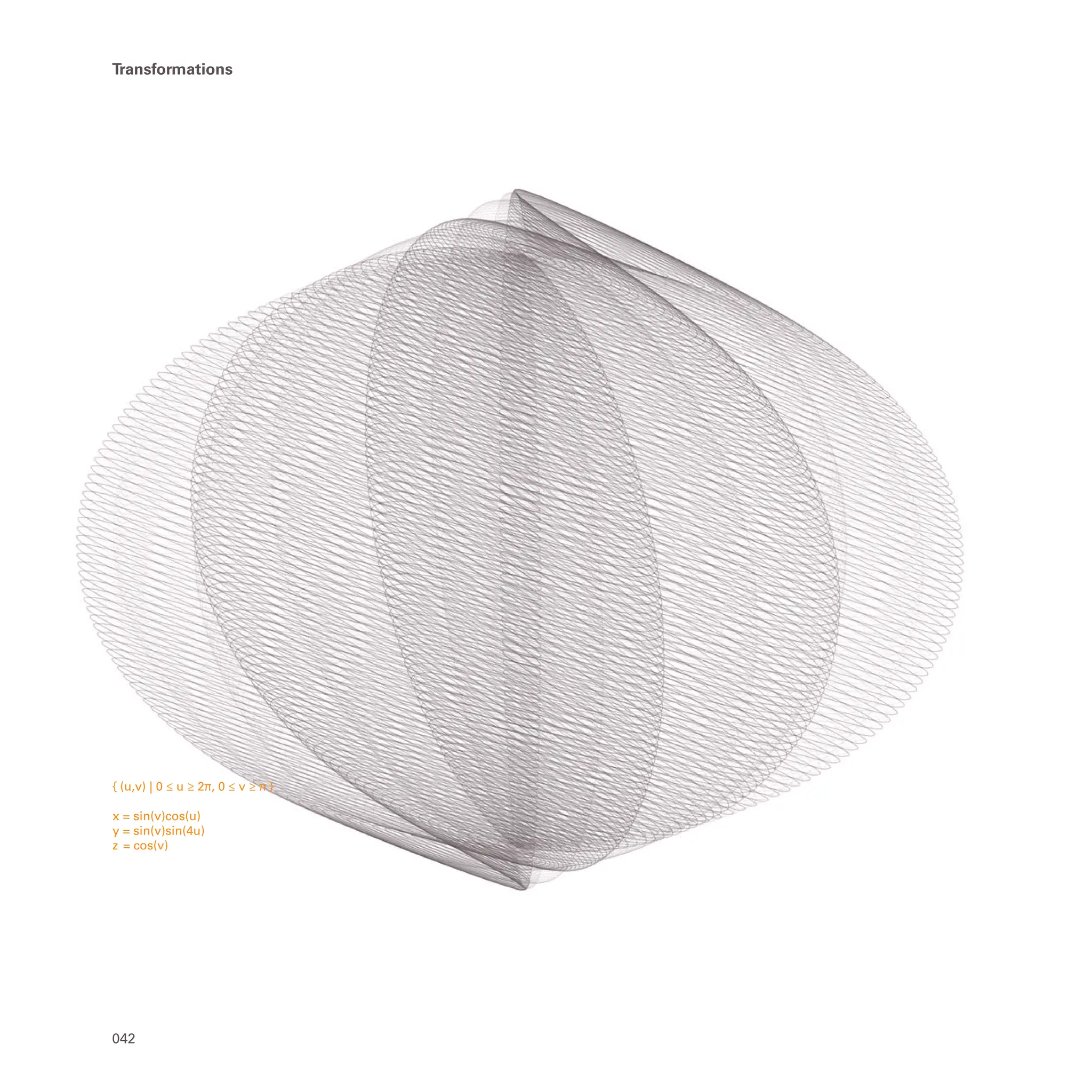

![043

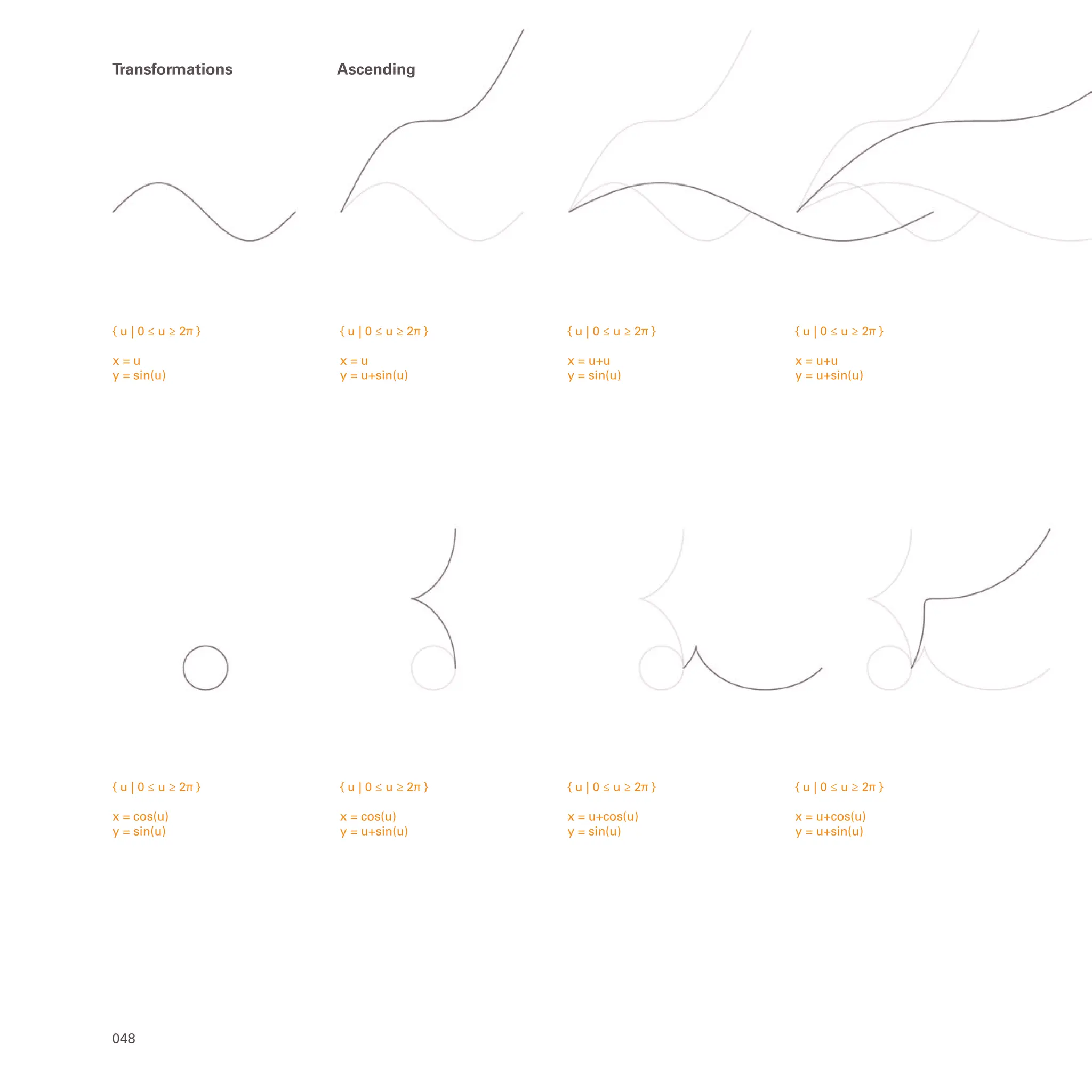

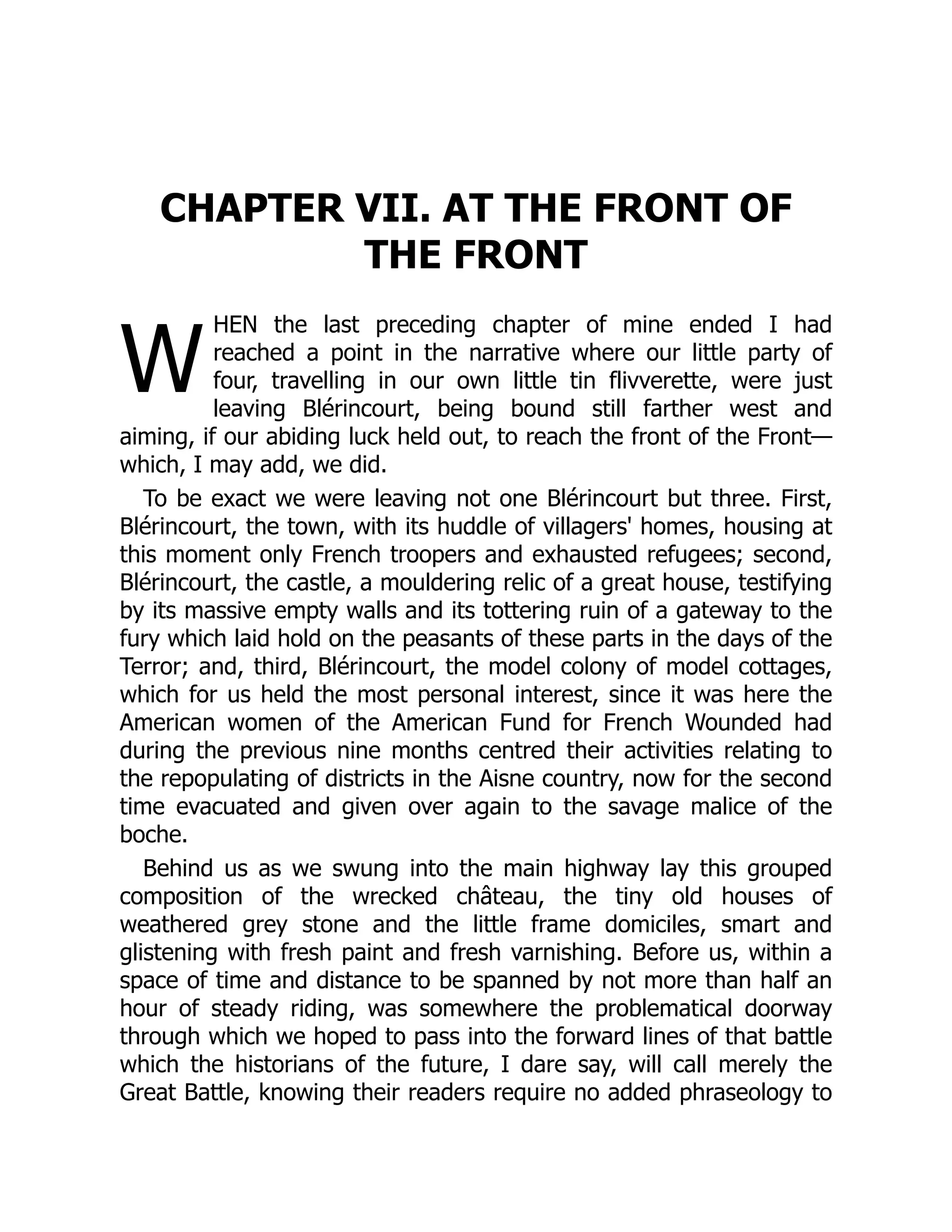

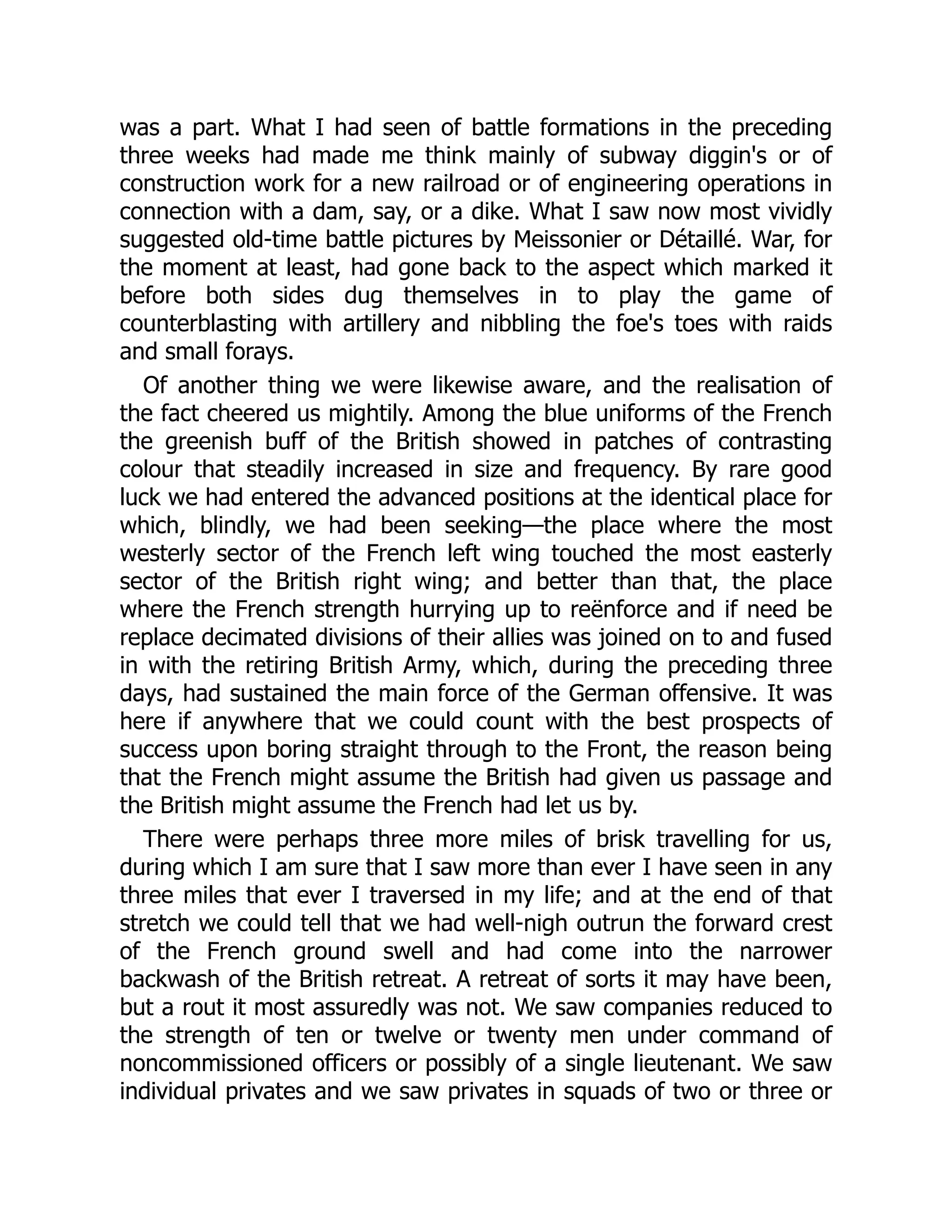

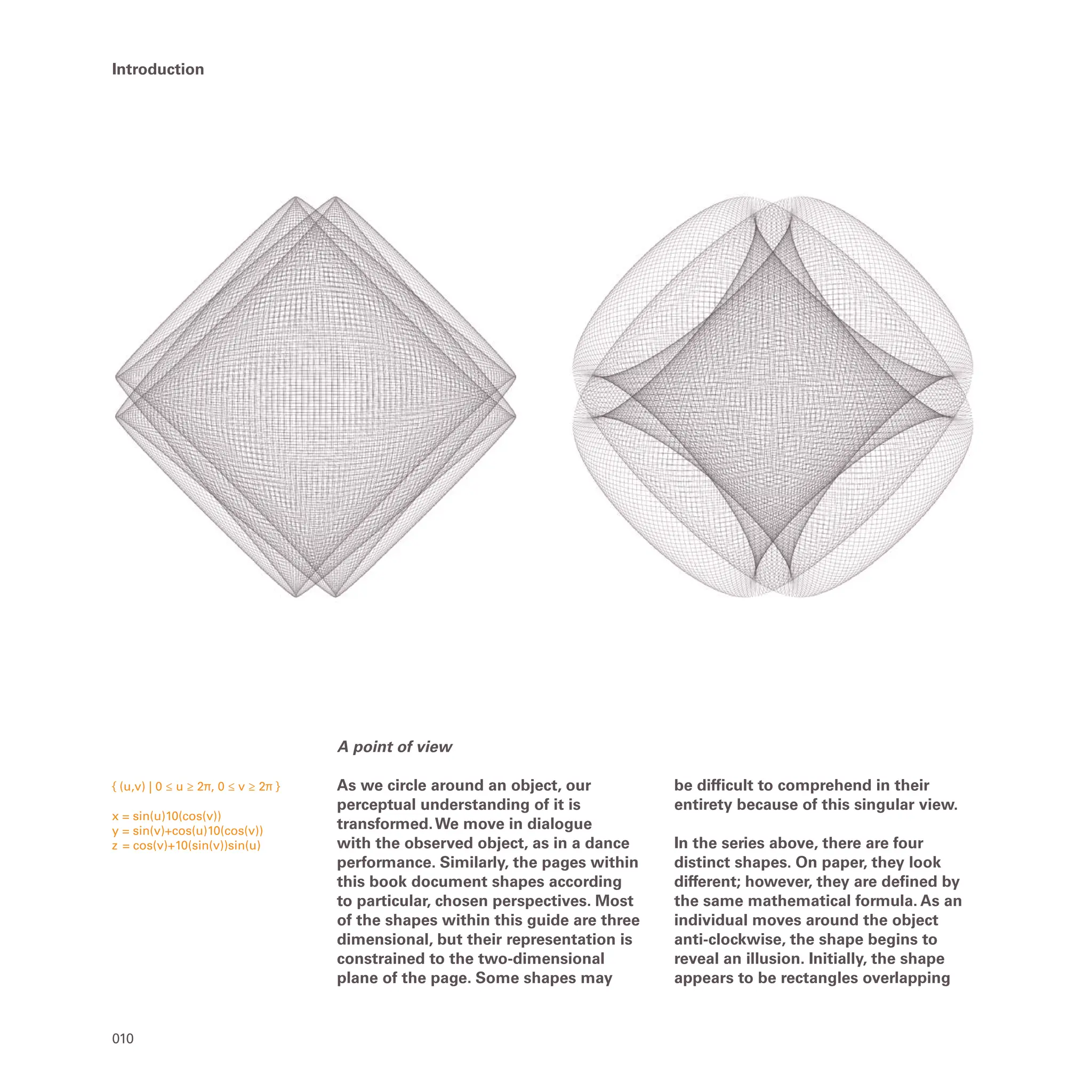

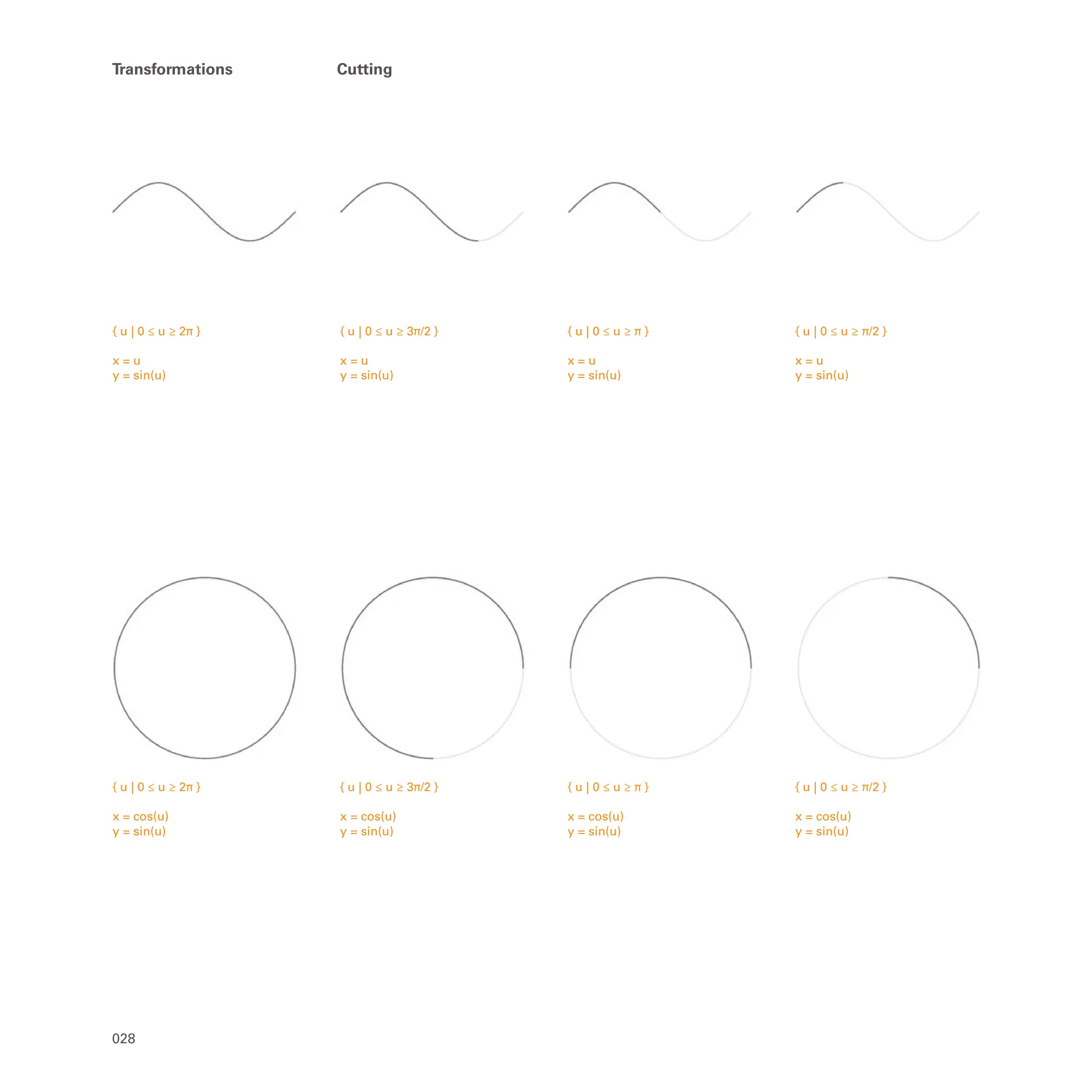

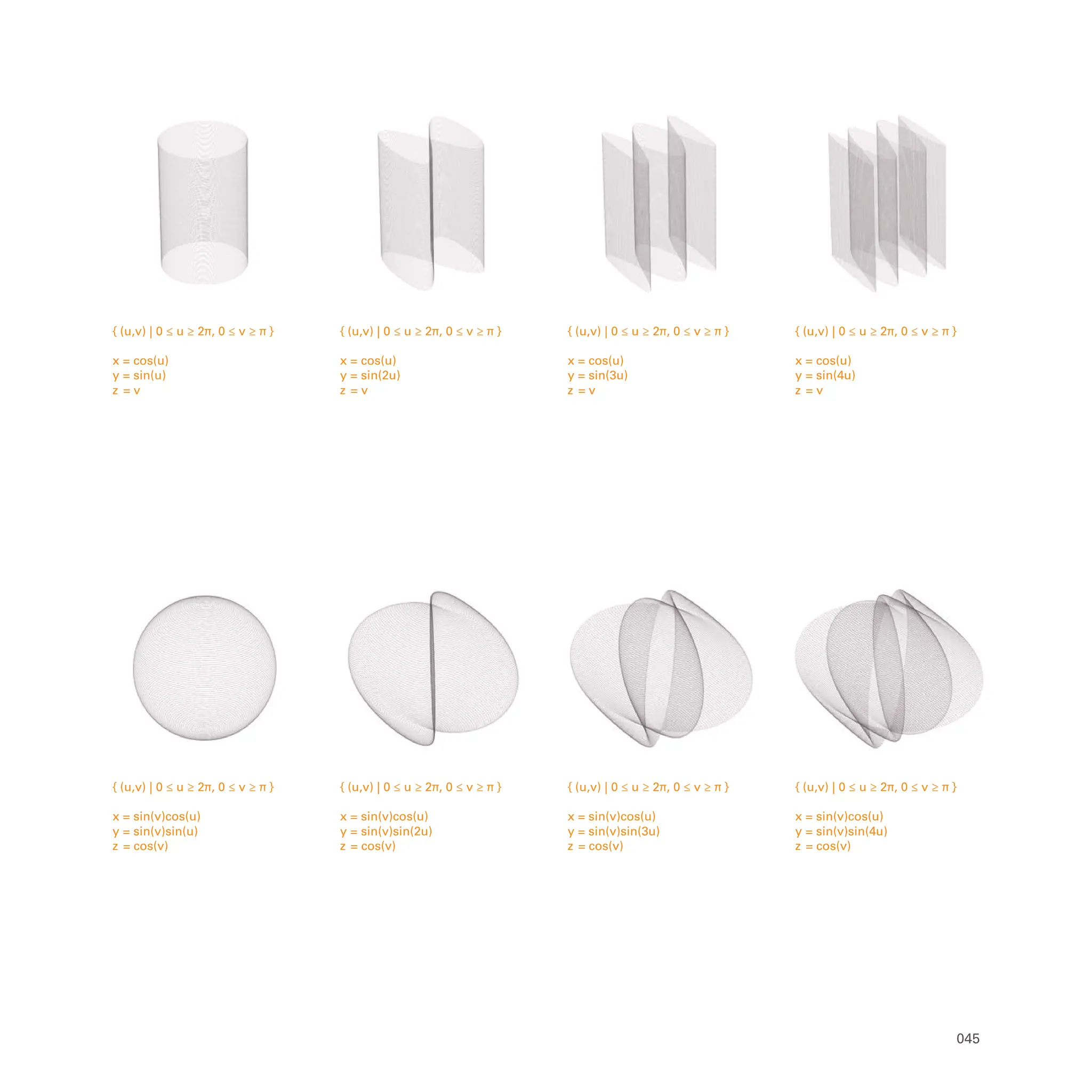

Within the trigonometric functions (sine, cosine) there are

parameters (u, v).Within cutting, these parameters control the

end points of a curve. However, when these parameters are

scaled while embedded inside a trigonometric function [for

example, sin(A(u)), where A is a scaling factor], they control the

frequency of the curve defined. For example, if the parameter is

doubled, the output would yield double the number of periods

over the same length. Multiplying the parameter also multiplies

the frequency of the curve.

Modulating](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5900846-250605004241-0eade27b/75/Morphing-A-Guide-To-Mathematical-Transformations-For-Architects-And-Designers-Choma-48-2048.jpg)

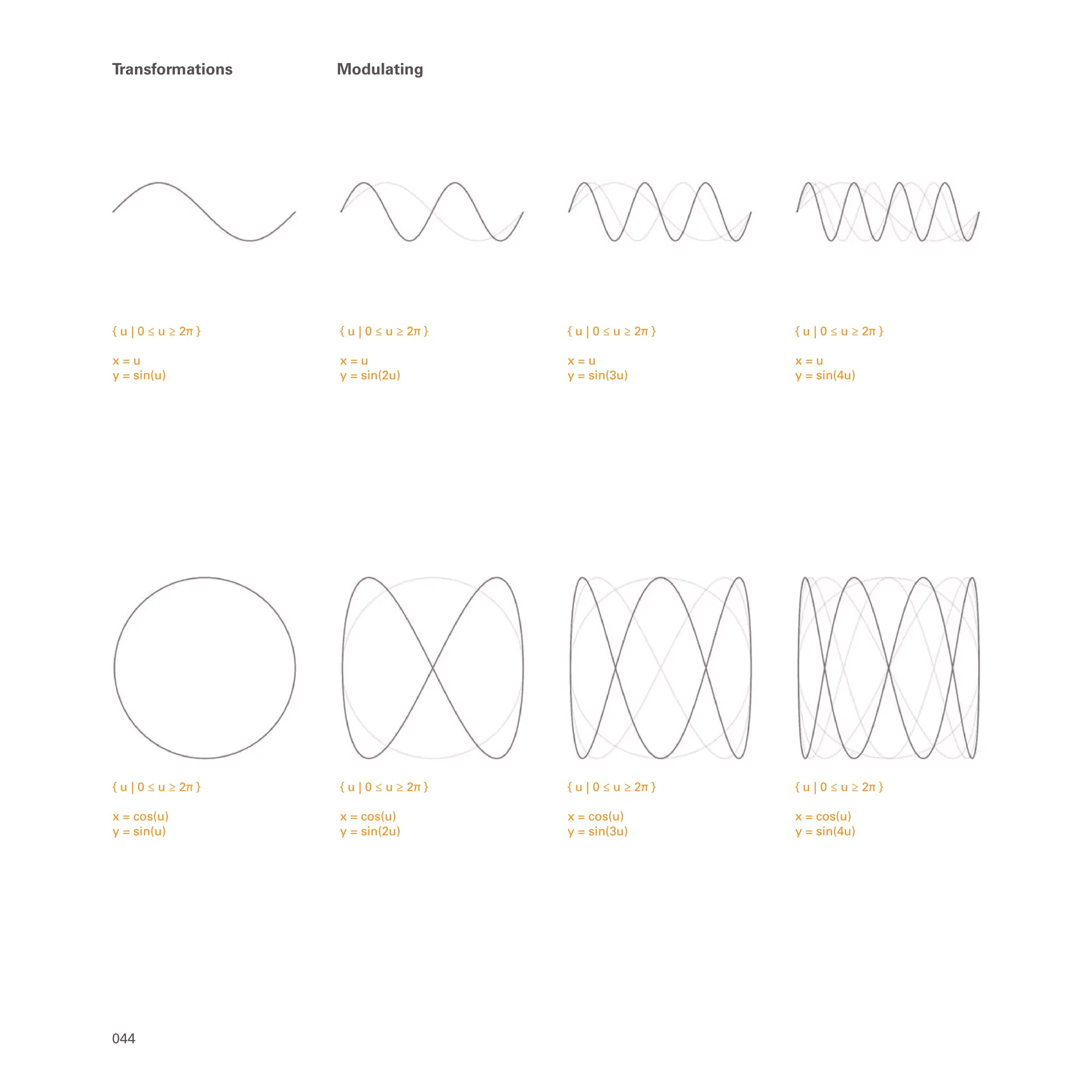

![047

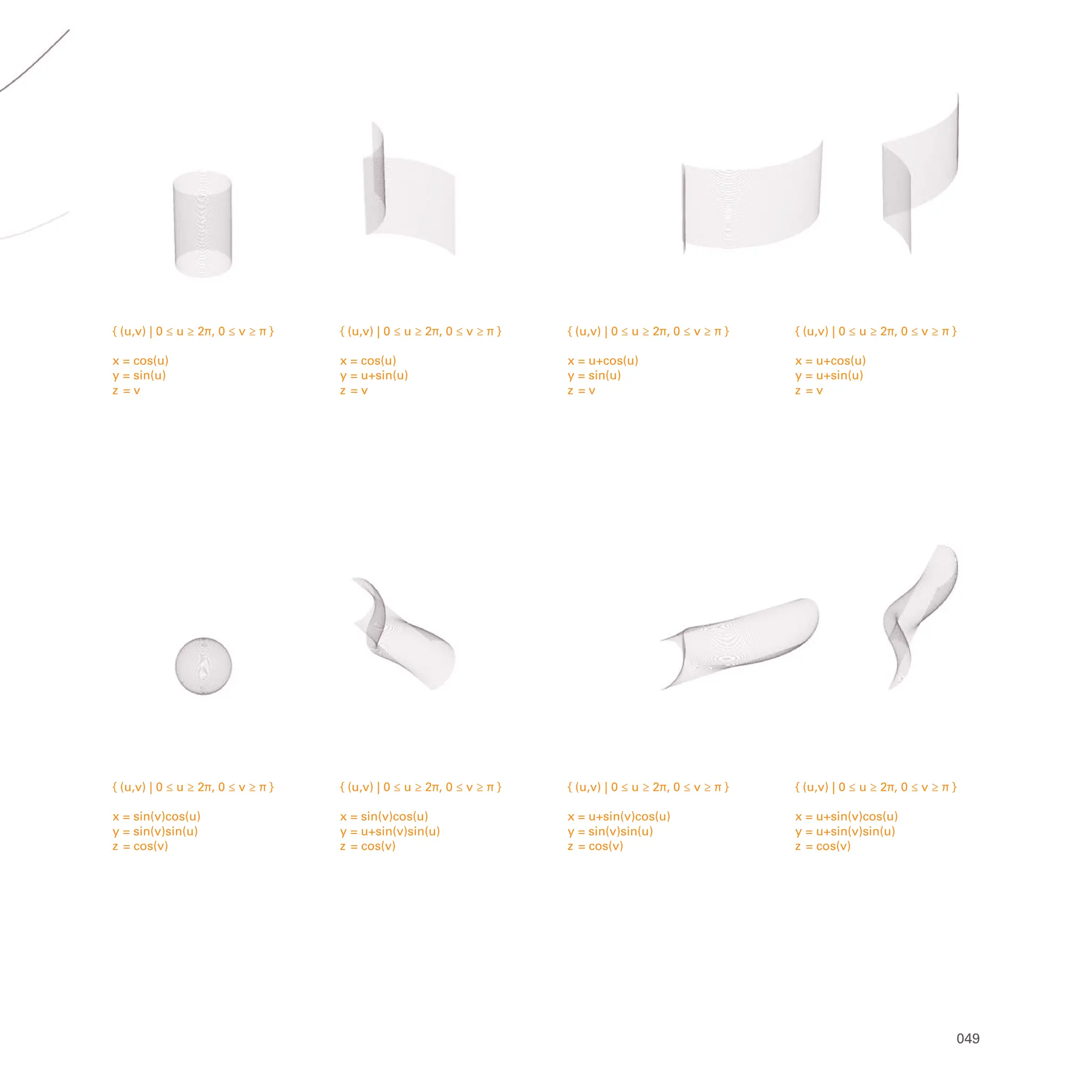

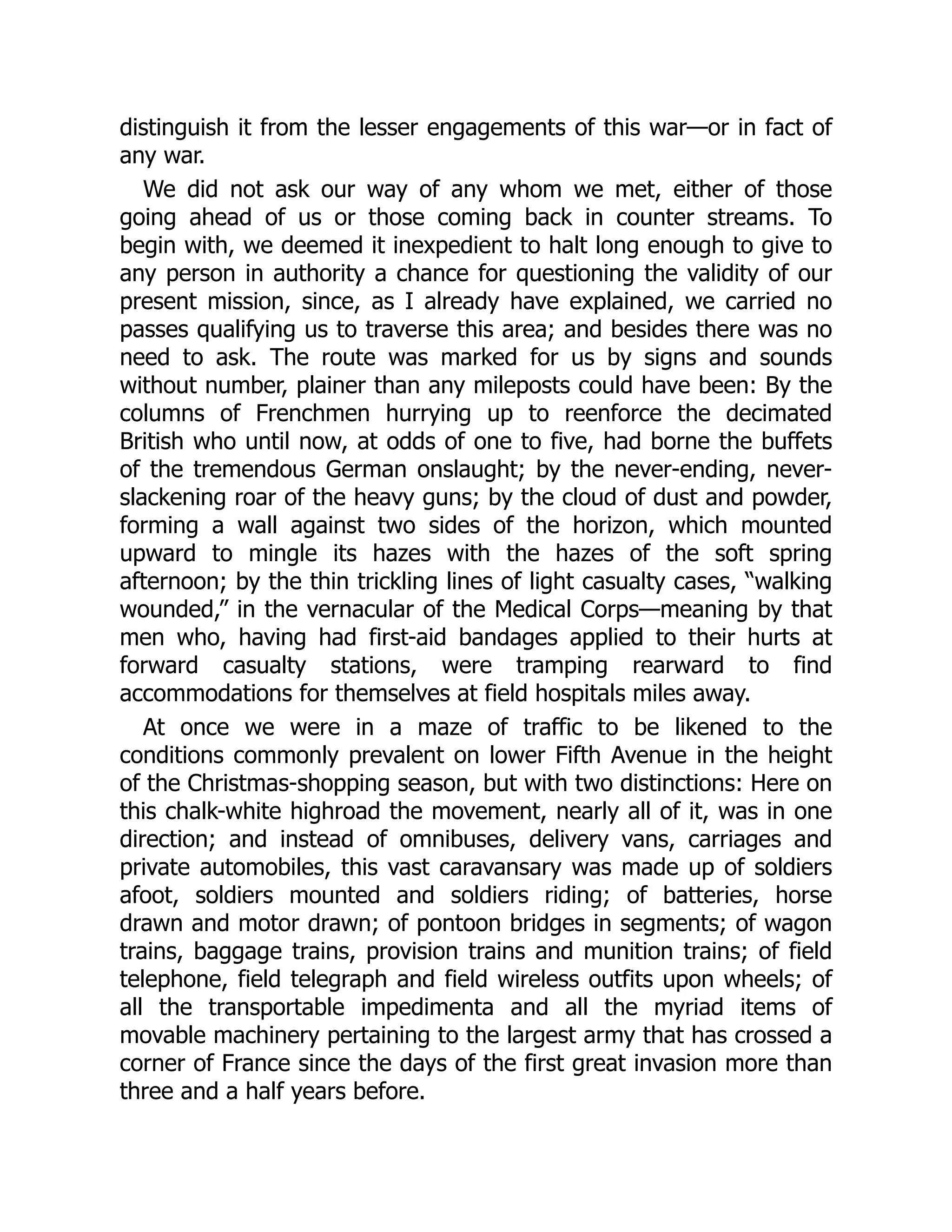

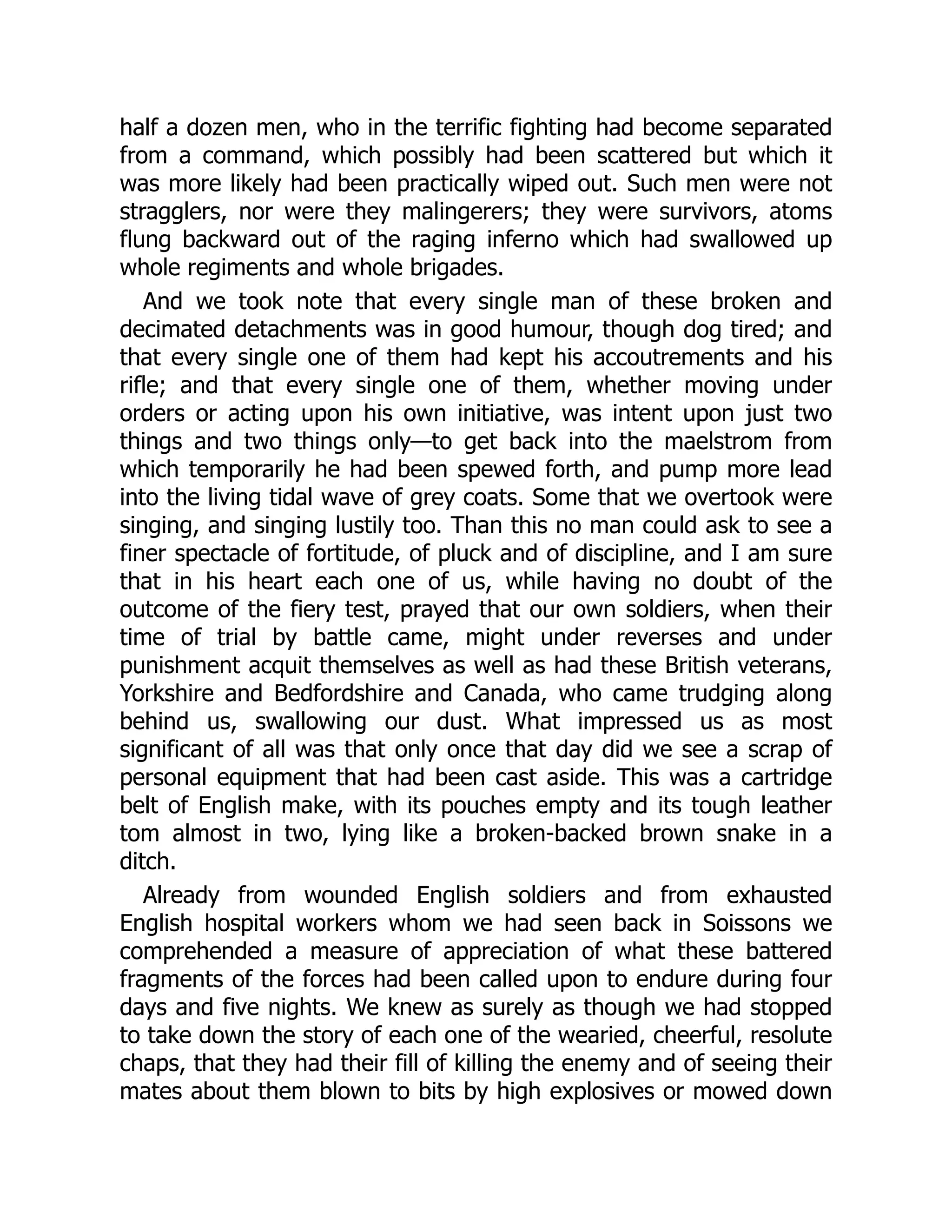

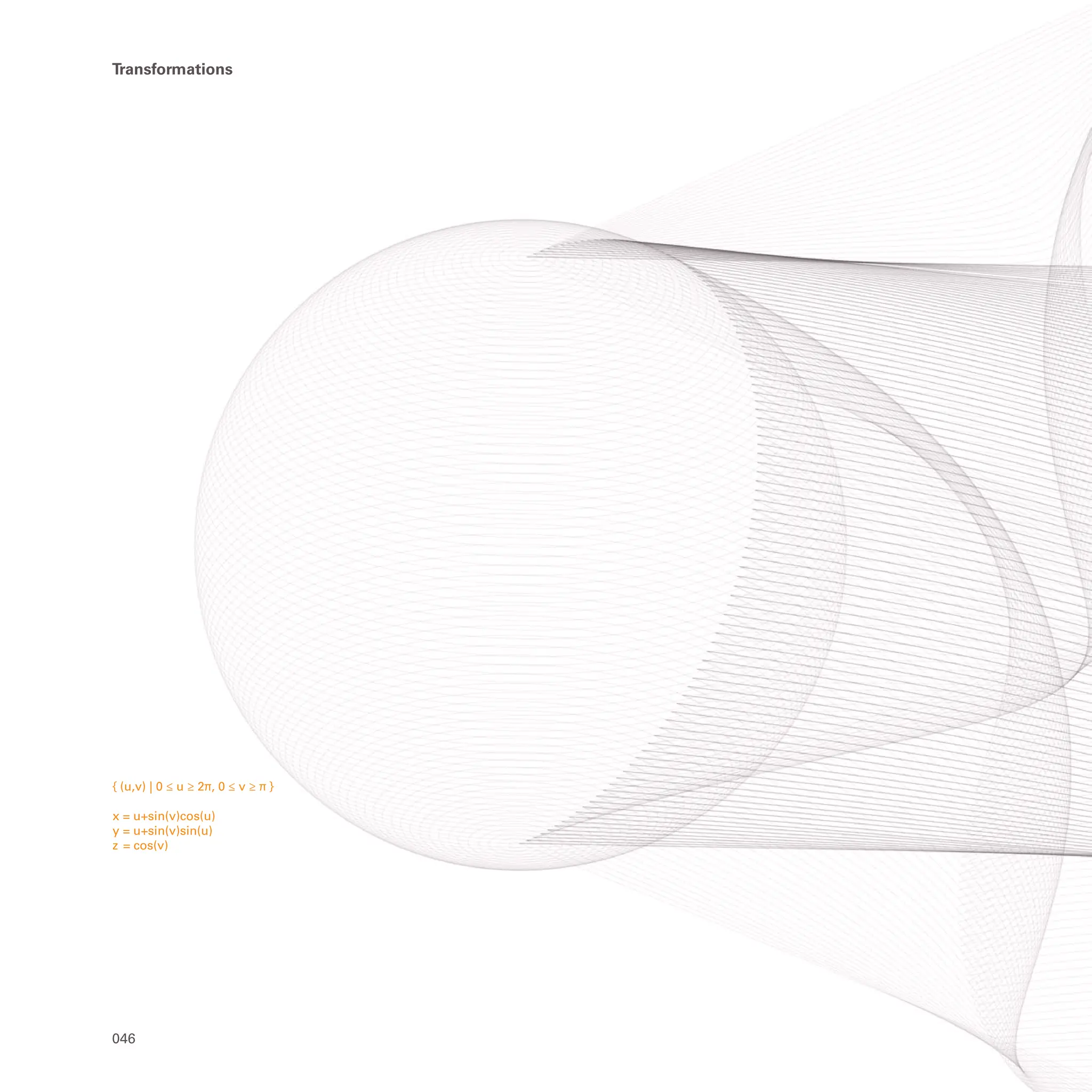

Imagine a piece of graph paper with an x-axis and a y-axis.

If a sine curve was drawn on the x-axis, its period would start

and end on the x-axis. Plotting a sine curve is much like plotting

a horizontal line, with undulations of a specific amplitude and

frequency. Adding a u-parameter outside the trigonometric

function [for example, u+sin(u)] is much like plotting a diagonal

line at an angle to the horizontal. For every cycle the function

completes, it incrementally moves vertically.The centre of the

sine curve would no longer follow the x-axis; instead, it would

follow the newly plotted diagonal line. Adding an integer

to a function would give a linear translation, while adding

a u-parameter would shift the shape and produce a

diagonal trajectory.

Ascending](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5900846-250605004241-0eade27b/75/Morphing-A-Guide-To-Mathematical-Transformations-For-Architects-And-Designers-Choma-52-2048.jpg)