This document provides an overview of a training manual on microinsurance for disaster risk reduction. The summary is:

1) The training manual was developed by AIDMI to address gaps in training materials on microinsurance and CBDRR.

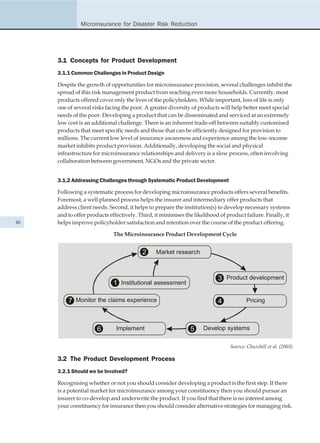

2) It includes 4 modules that can be used individually or together in a day-long training session.

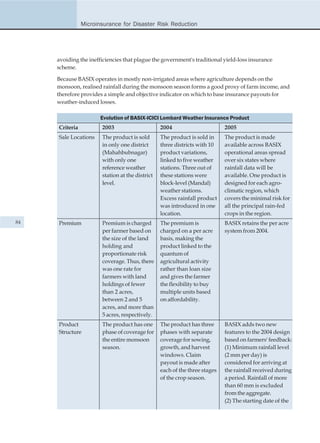

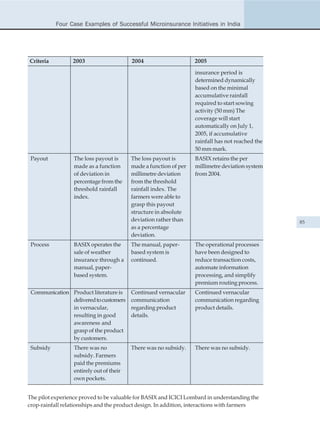

3) The modules aim to increase awareness of microinsurance and provide examples of successful microinsurance programs in India.

. Rising from the Ashes: Development Strategies in

Times of Disaster. London: IT Publications.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/micro-insurance-module-tlc-india-1278252234-phpapp02/85/Micro-Insurance-Module-T-L-C-India-92-320.jpg)