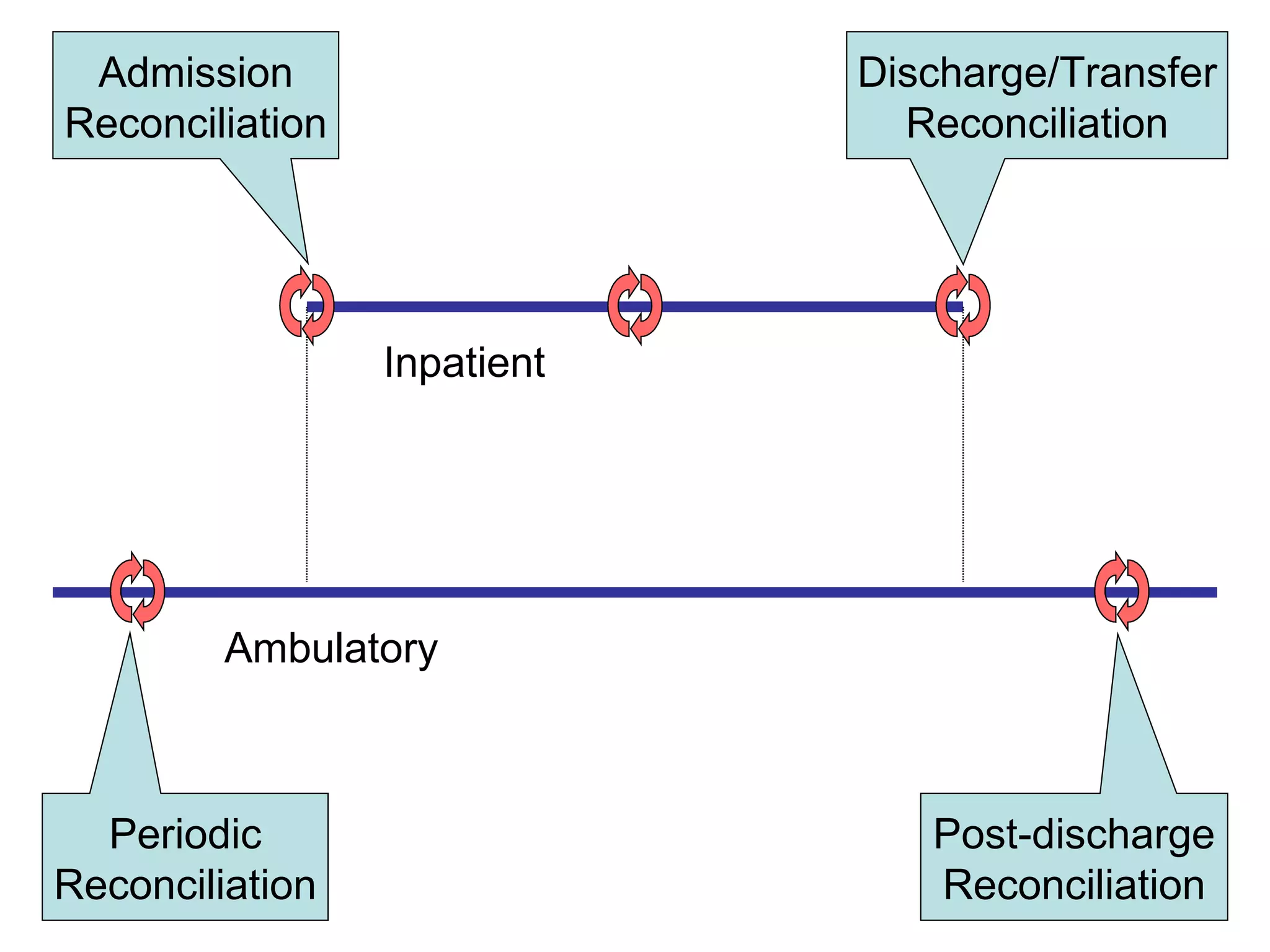

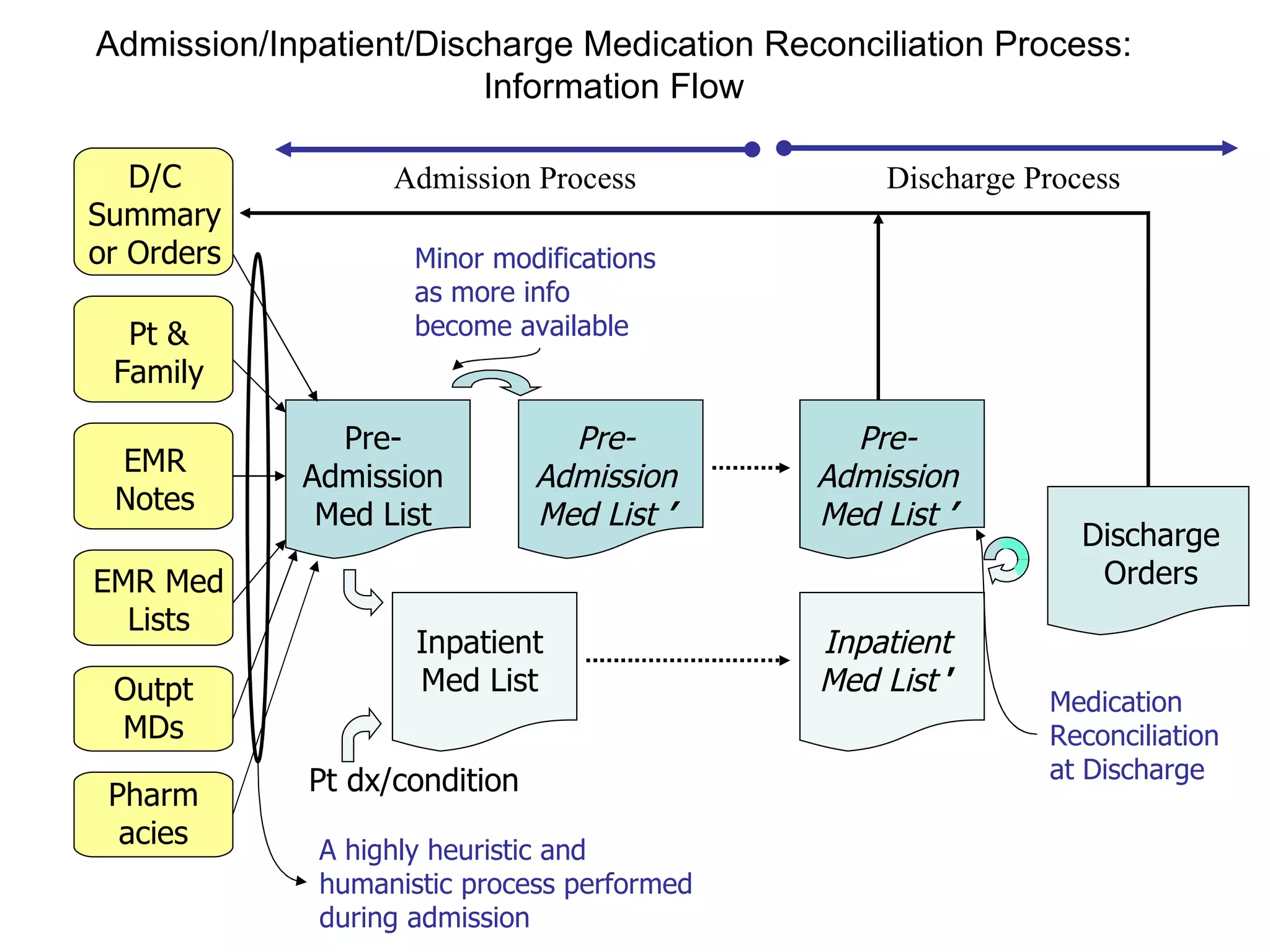

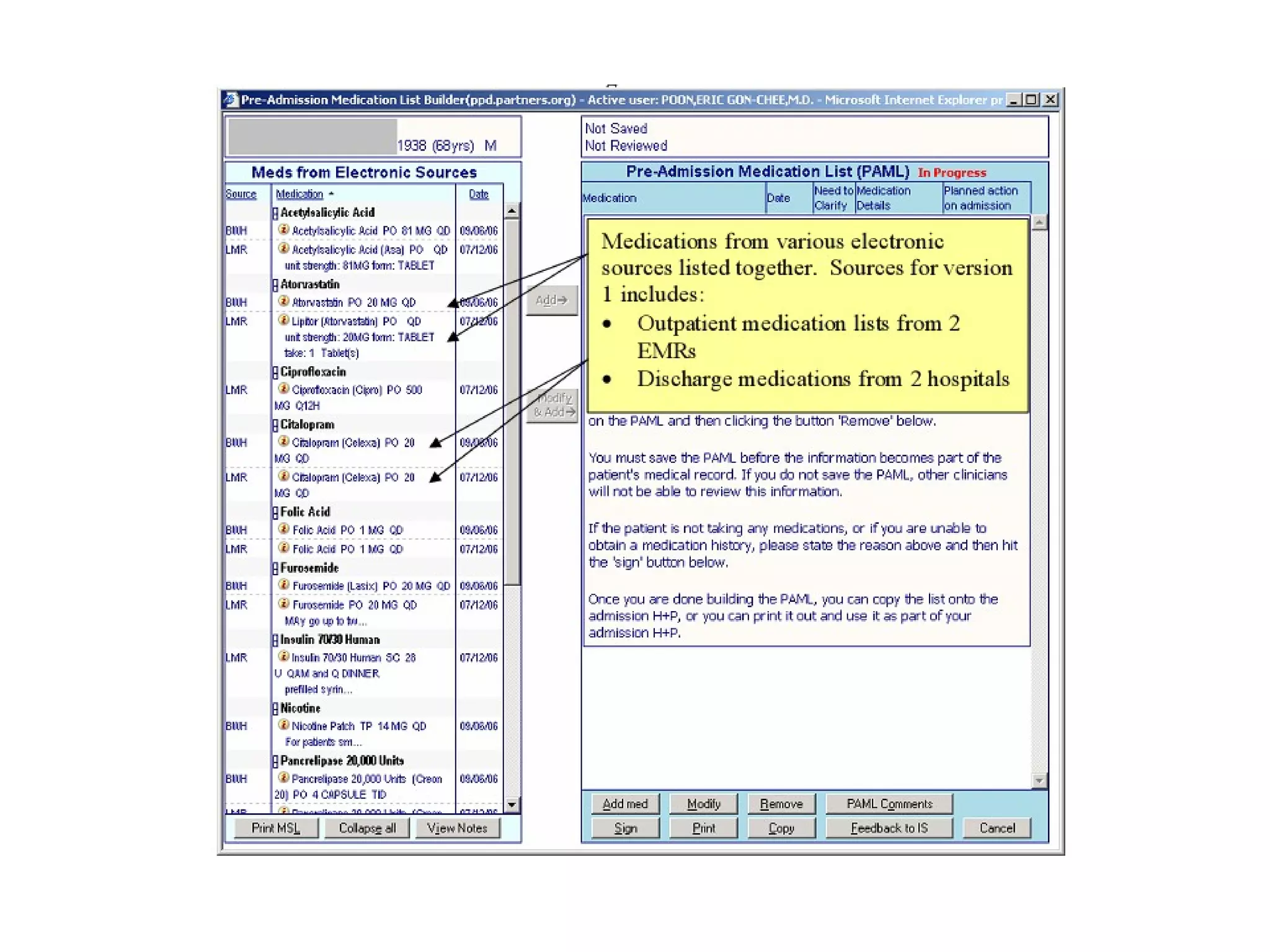

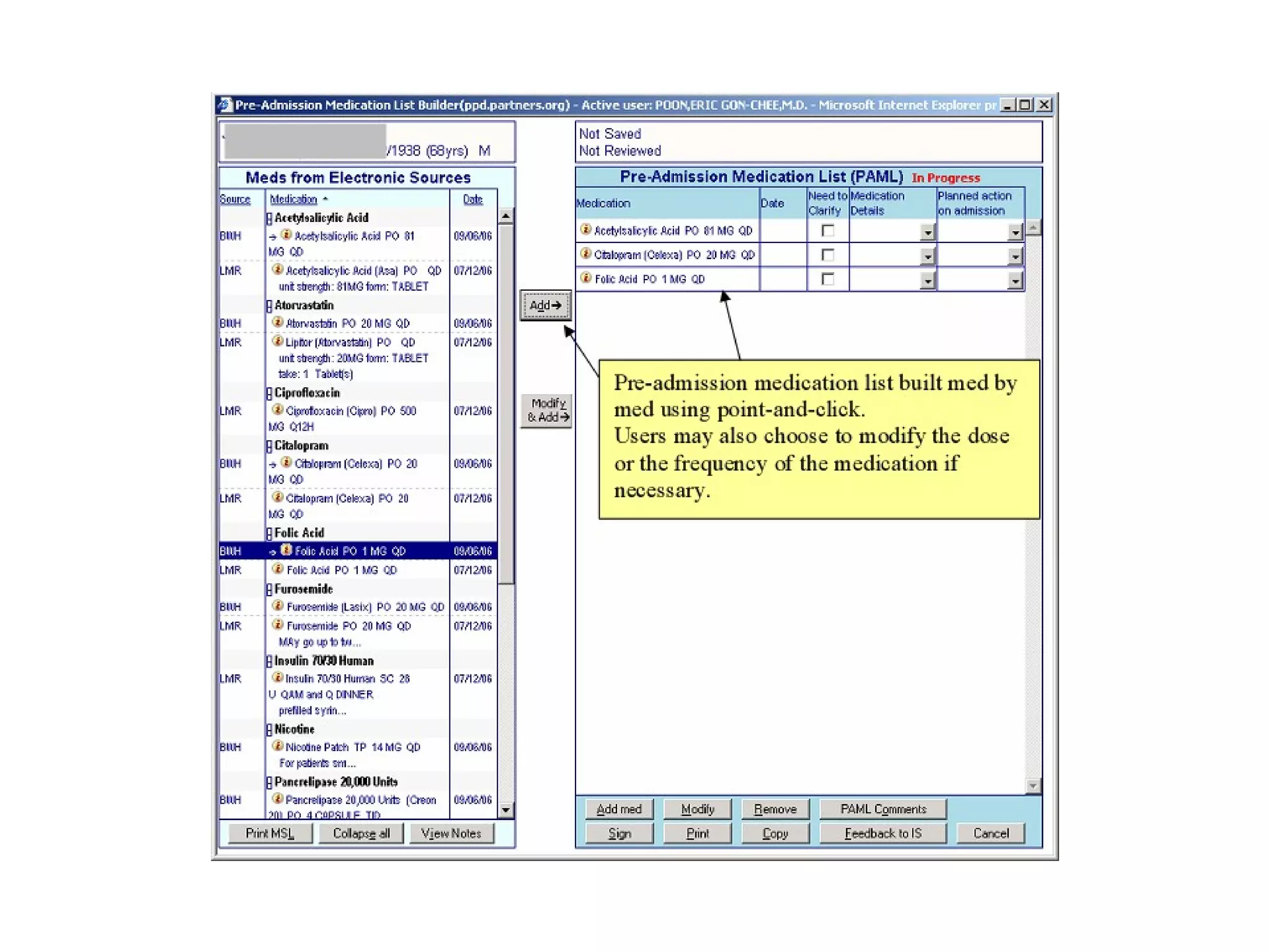

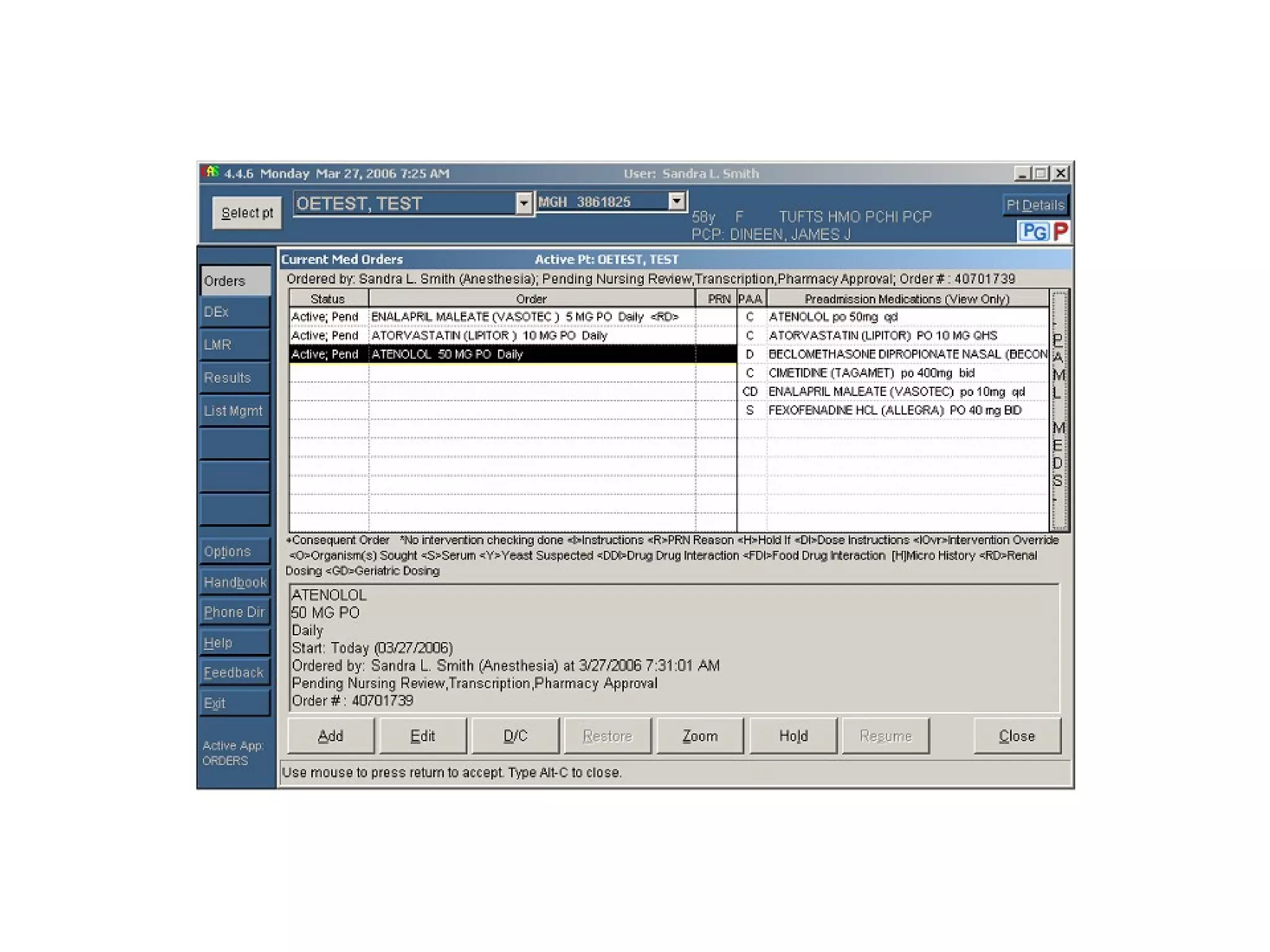

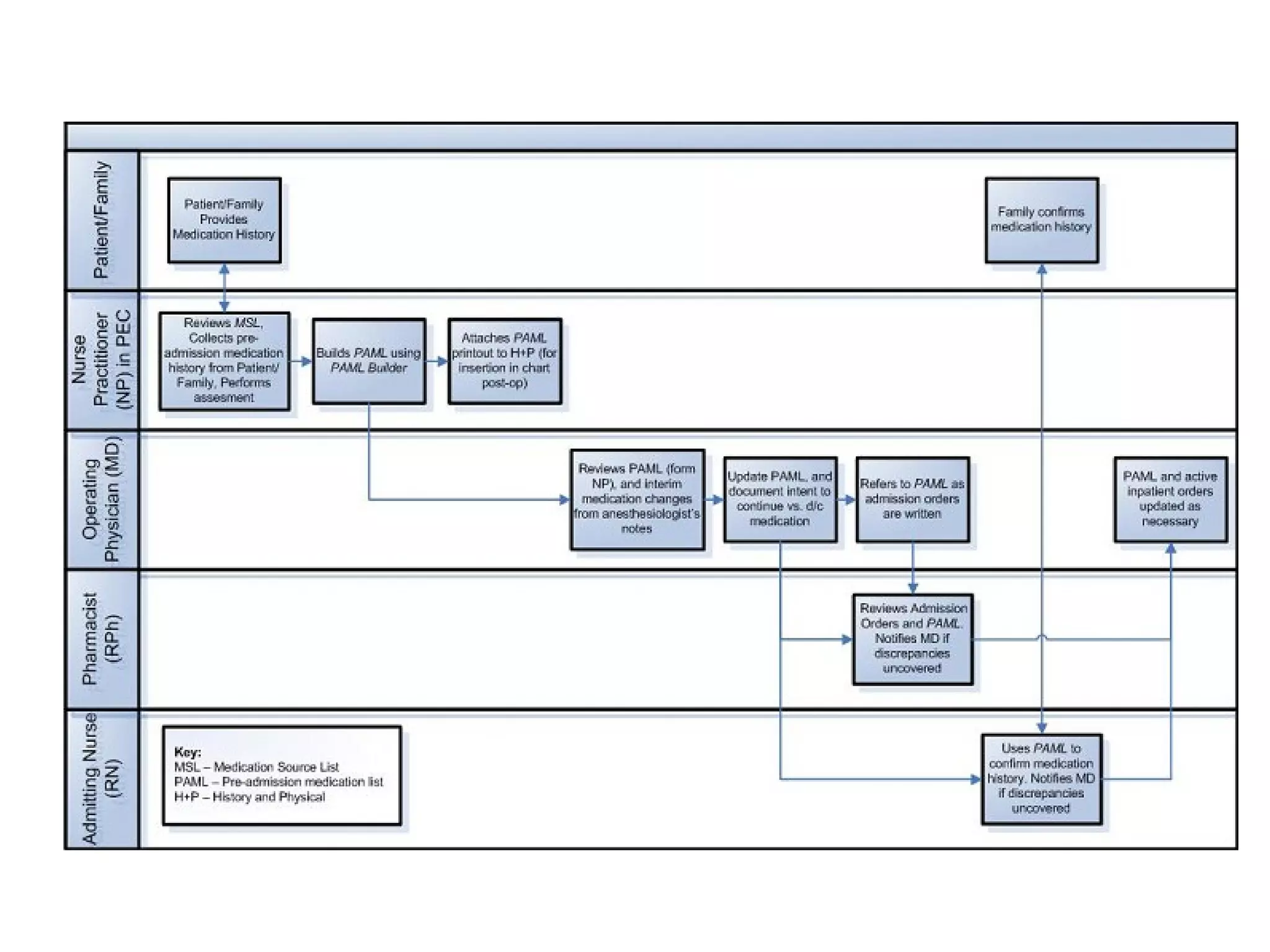

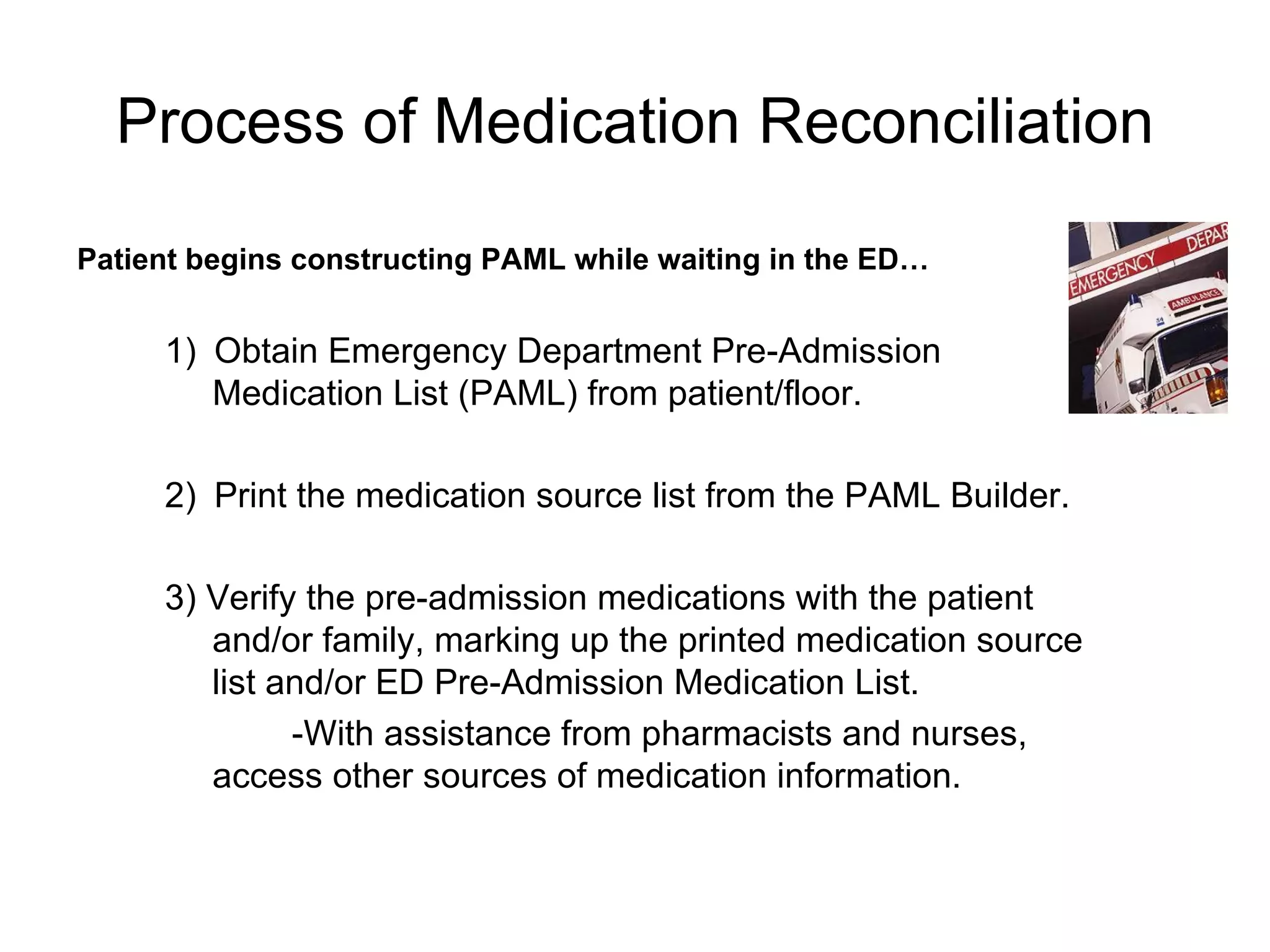

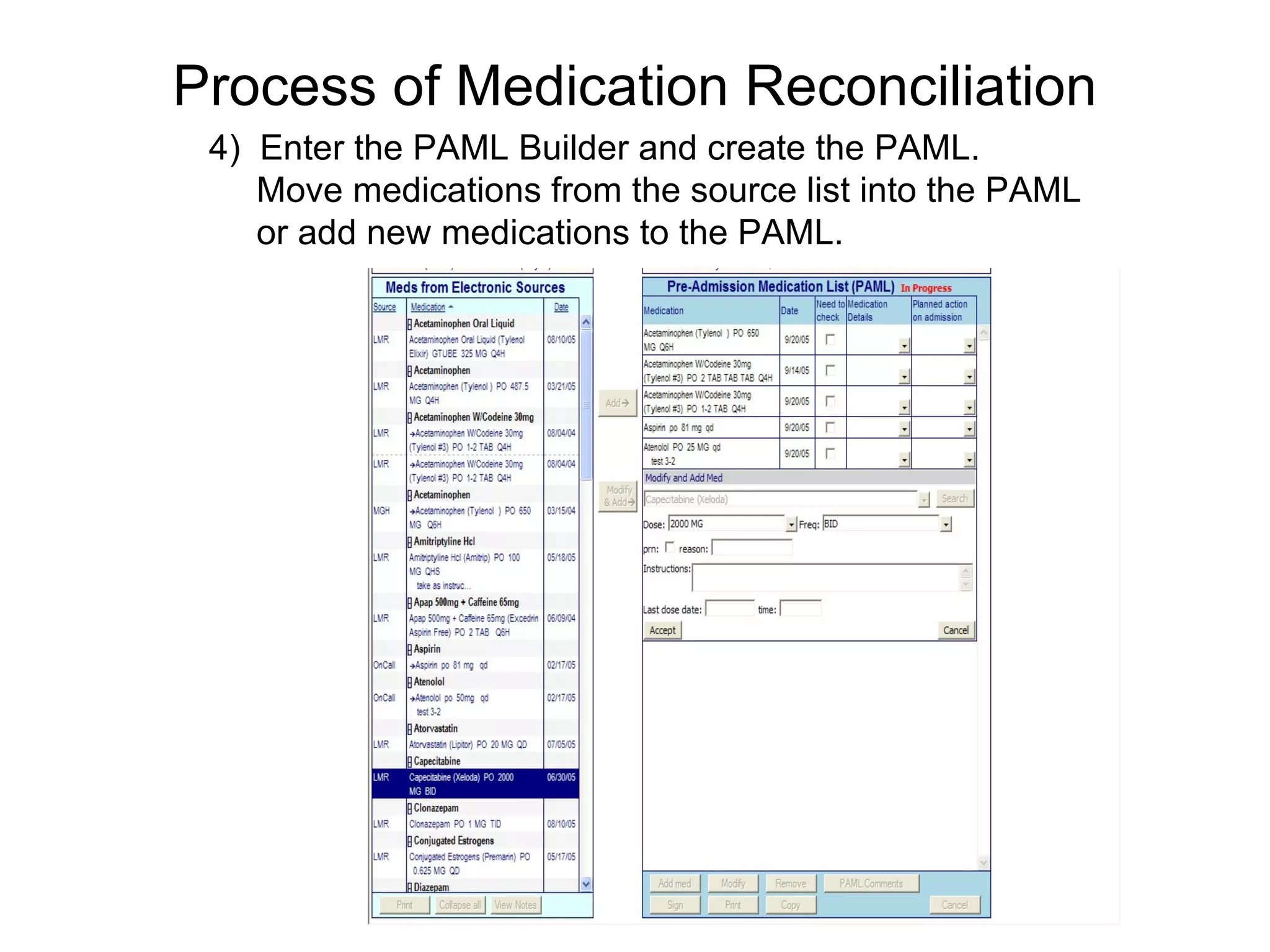

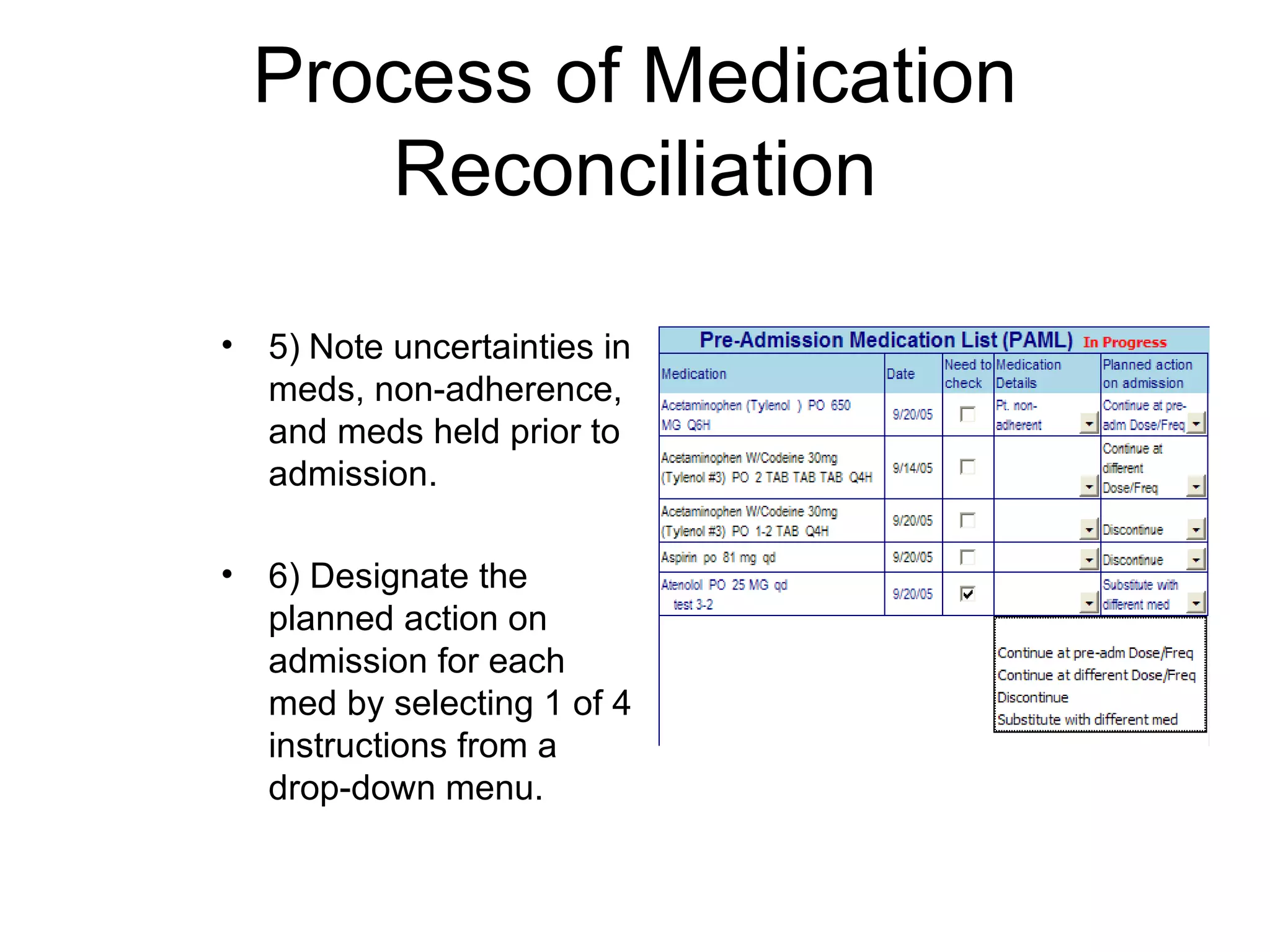

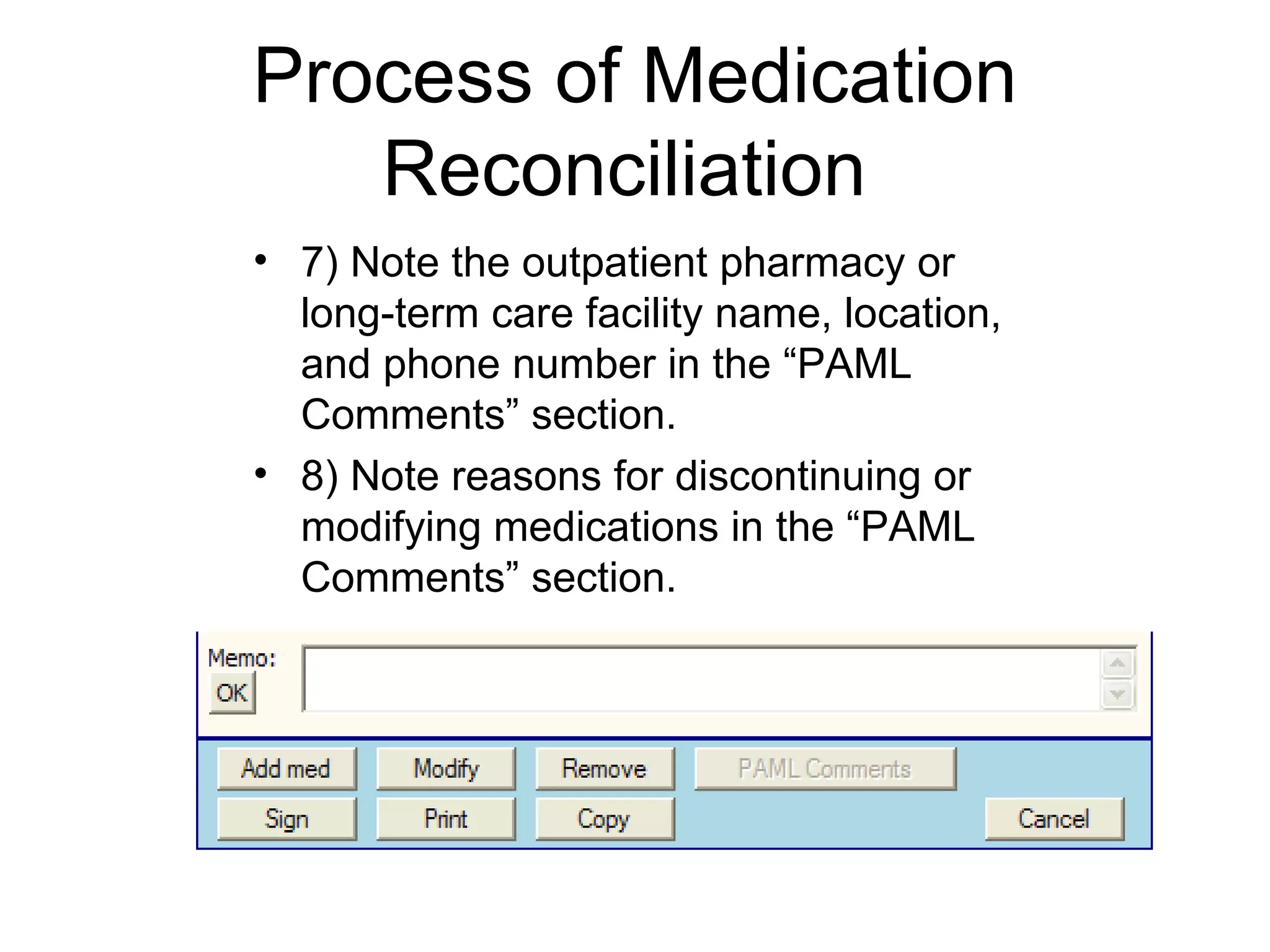

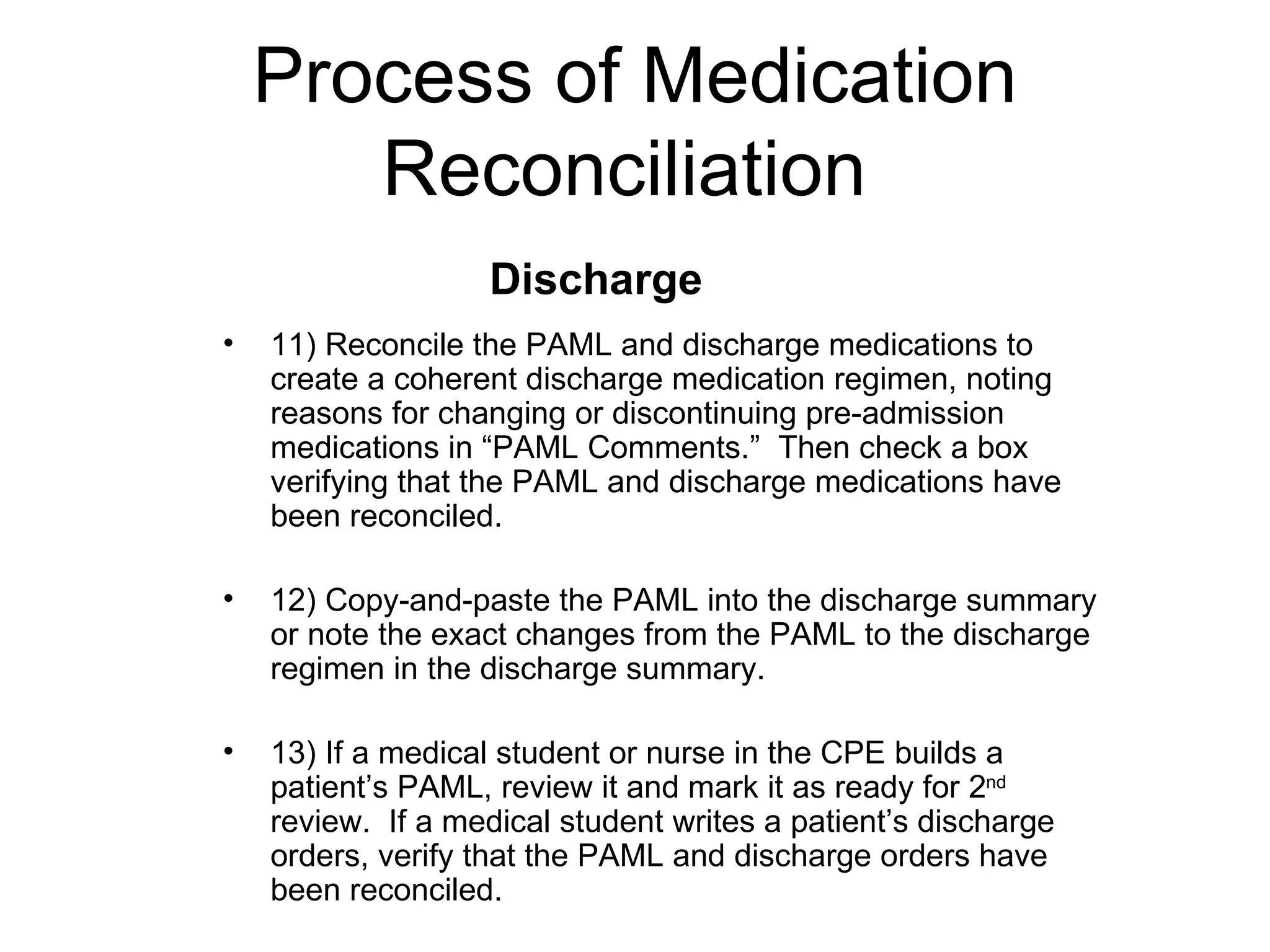

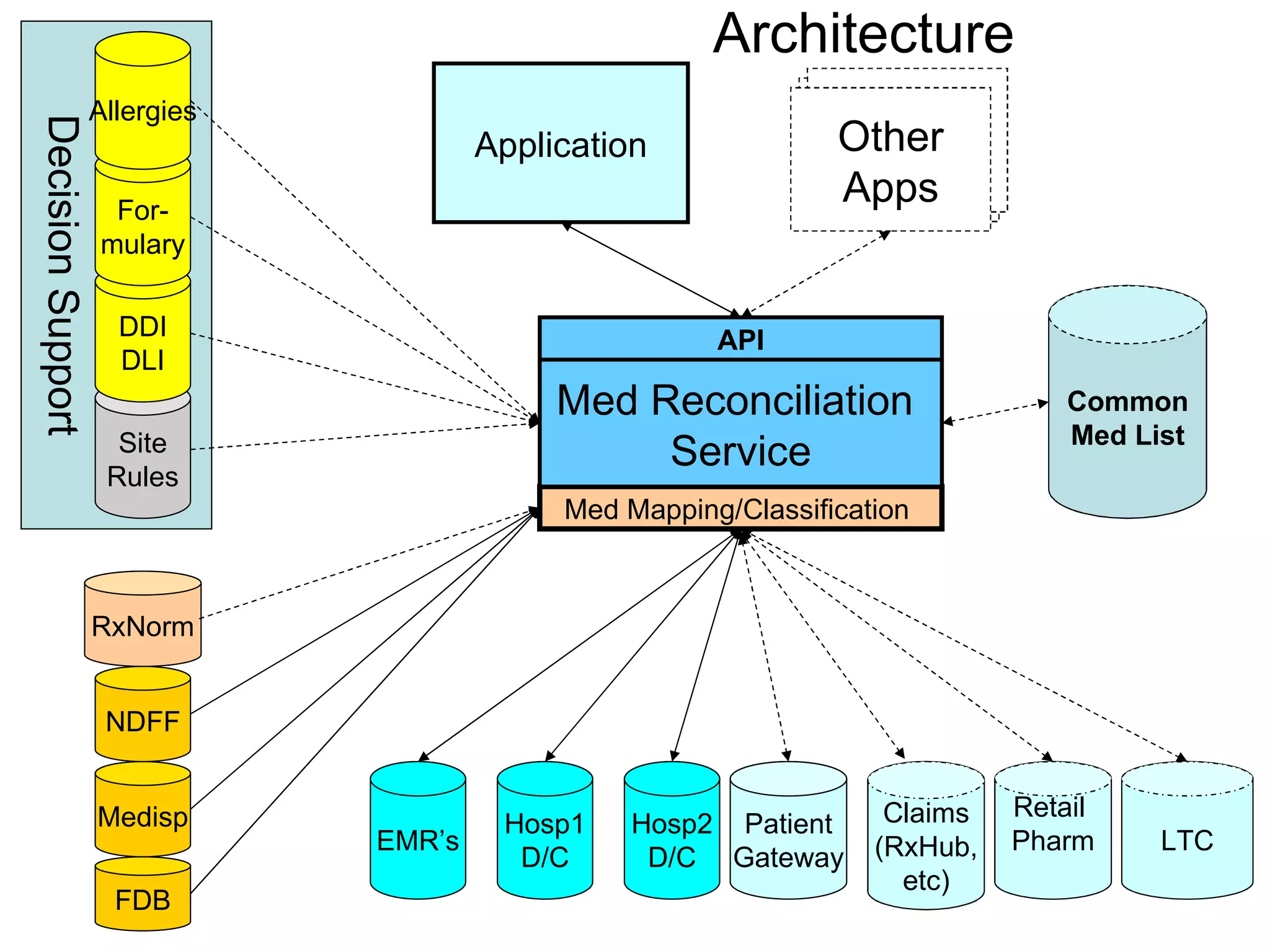

The document discusses medication reconciliation, which is defined as a process to obtain and document a complete list of a patient's pre-admission medications and reference this list when writing admission, transfer, and discharge orders. It provides background on medical errors from medication issues and the importance of medication reconciliation. It then describes the medication reconciliation process, which involves verifying the patient's medication list with them and reconciling the list at discharge.

![The Problem Limited ability to exchange drug information Can electronically exchange some information about packaged drug products (NDC 0006-0114-68, Lipitor 10mg tablets in bottles of 100) Cannot share other clinically useful concepts (atorvastatin [Lipitor] 50mg PO once daily)…due to lack of a standard (coded) terminology for exchange](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/MedRecandTerminologytoMCP2008-090220081310-phpapp02/75/Med-Rec-And-Terminology-To-Mcp-2008-31-2048.jpg)