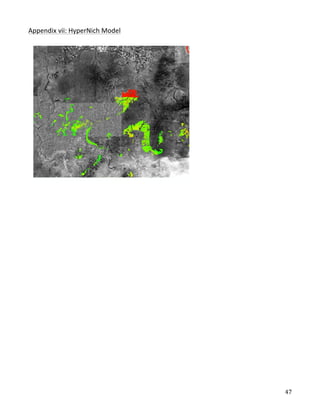

This document describes the creation of habitat distribution models for the endemic plant species Astragalis anserinus. The author collected environmental data for the species' range and used MaxEnt modeling in the R statistical programming language to create two habitat distribution models, MaxEnt1 and MaxEnt2. Both models were evaluated using metrics like AUC. A combination of the two models was used to make a final recommended habitat map. However, the author notes that some presence data points may be inaccurate and require field verification. An improved model incorporating verified data is recommended. The modeling provides a cost-effective way to predict habitat compared to solely using fieldwork.

![51

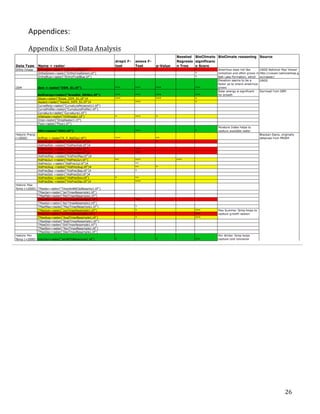

Appendix

ix:

Sample

R

code

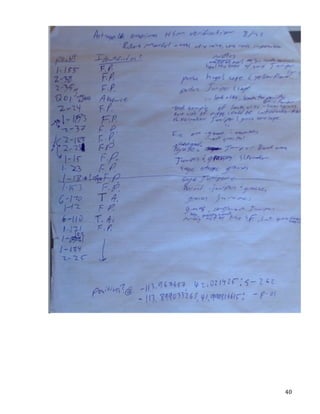

####

MaxEnt

Code

Example

####

Robert

Machol

####

UofU

-‐

MST

&

UDAF

####

Ded

2014

##Set

working

directory

setwd("~/Documents/MST/Summer

2014/Final

Project")

##Load

dismo

library

library("dismo",

lib.loc="/Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/3.1/Resources/library")

##Load

maptools

library("maptools",

lib.loc="/Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/3.1/Resources/library")

##rgdal

library("rgdal",

lib.loc="/Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/3.1/Resources/library")

##

proj4

spatial

plotting

library("proj4",

lib.loc="/Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/3.1/Resources/library")

##scales-‐

for

transparnt

plotting

library("scales",

lib.loc="/Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/3.1/Resources/library")

##Corgram

to

view

colinearity

library("corrgram",

lib.loc="/Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/3.1/Resources/library")

##MASS

to

write

Matrix

library("MASS",

lib.loc="/Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/3.1/Resources/library")

#####Load

rasters

#####

##

cut

from

171

rasters

to

6

according

to

'DataFileList.xlsx'

##

@

30m

resolution

dem

=

raster("RasterOutput/DEM_S1.tif")

SolEnergy=raster("RasterOutput/AreaSol_DEMs1.tif")

IMI=raster("RasterOutput/IMI1.tif")

TmaxJul8110=raster("RasterOutput/PRISMTmax8110Jul.tif")

tmin8110Feb

=raster("RasterOutput/PRISMtmin8110Feb.tif")

HisPrecJun

=

raster("RasterOutput/HisPrecJun1.tif")

#

Envirofiles

Stack

envirofiles

=

(c(dem,SolEnergy,IMI,TmaxJul8110,tmin8110Feb,HisPrecJun))

enviropredictors=(stack(envirofiles))

summary(enviropredictors)

#####Load

Points######

##

Presence

points:

Points

=

read.csv("PresentFinal.csv")

Points

##

I

only

want

the

coordinates...

Pointsxy

=

Points[,1:2]

Pointsxy

#787

points

##Absence

Points:

Absence

=

read.csv("NegsFinal.csv")

Absencexy

=

Absence[,1:2]

Absencexy

#362

points

#tail(Absencexy)

####

Points

&

Coordinate

Metadata:

####](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4f0642fe-ff34-400e-9d28-12ccf8090a4b-150407130702-conversion-gate01/85/MacholInternship5-51-320.jpg)

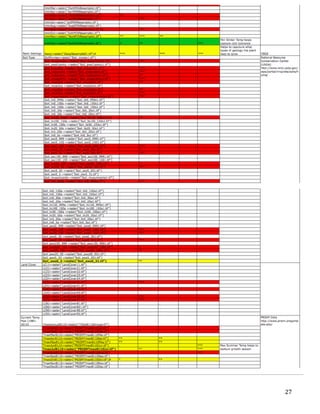

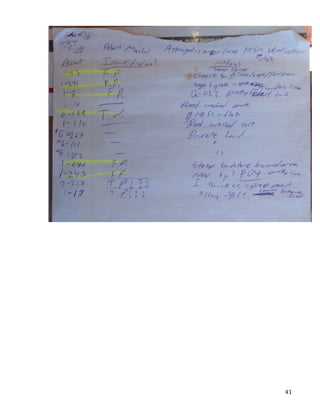

![52

##cooridinates

for

study

area:

42.47,41.24

&

-‐114.88,-‐113.42

##Geographic

Coordinate

System:

GCS_WGS_1984

##Datum:

D_WGS_1984

##Prime

Meridian:

Greenwich

##Angular

Unit:

Degree

####

Plot

Points:

####

par=(mfrow=c(1,1))

PointsCRS

=

CRS("+proj=longlat

+ellps=WGS84")

Points.sp

=

SpatialPoints(cbind(Pointsxy$XCoord,

Pointsxy$YCoord),

proj4string=PointsCRS)

summary(Points.sp)

bbox(Points.sp)

proj4string(Points.sp)

coordinates(Points.sp)

Points.spdf

=

SpatialPointsDataFrame(cbind(Pointsxy$XCoord,

Pointsxy$YCoord),

Pointsxy,

proj4string

=

PointsCRS)

summary(Points.spdf)

plot(Points.spdf)

###

General

visualization

of

point

data

###

##USA

Download

USA

=

getData('GADM',

country='USA',

level

=

1)

Absence.spdf

=

SpatialPointsDataFrame(cbind(Absencexy$XCoord,

Absencexy$YCoord),

Absence,

proj4string

=

PointsCRS)

plot(USA,

xlim=c(-‐114.45,

-‐113.9),

ylim=c(41.6,42.1),

axes=TRUE)#Point

Coordinates

points(Pointsxy$XCoord,

Pointsxy$YCoord,

col=alpha("green",

0.3),

cex=.5,

pch=3)#Include

accual

and

random

from

survey

plots

points(Absencexy$XCoord,

Absence$YCoord,

col=alpha("red",

0.3),

cex=.5,

pch=4)#Include

accual

and

random

from

survey

plots

legend("topleft",

legend

=

c("Presence

-‐

787

points",

"Absence

-‐

362

points"),

col

=

c("green",

"red"),

pch

=

c(3,4)

)

title(

main="A.anserinus

Point

Data")

##All

predictors

plot

(enviropredictors)

#######

Extract

Values

From

Rasters

Via

Points

###########

##Presence

Values:

presvals=extract(enviropredictors,Pointsxy)#(RnR)

##Absence

VAlues

absvals=extract(enviropredictors,Absencexy)#(RnR)

##for

presence

or

absence

points,

we

will

call

"pb"

(new

variable,

0

absence

points,

1

presence

points)

pb

=c(rep(1,nrow(presvals)),

rep(0,nrow(absvals)))

##combine

these

points

into

a

singel

data.frame

admdata=data.frame(cbind(pb,rbind(presvals,absvals)))

names(admdata)

summary(admdata)

##vissually

check

for

Collinearity:

##Plot

data

in

pairs

pairs(admdata[,2:6],cex=0.1,

fig=TRUE)

library("corrgram",

lib.loc="/Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/3.1/Resources/library")

par(mfrow=c(1,1))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4f0642fe-ff34-400e-9d28-12ccf8090a4b-150407130702-conversion-gate01/85/MacholInternship5-52-320.jpg)

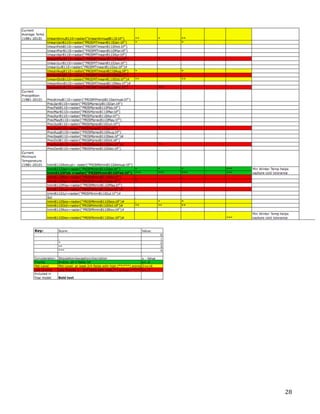

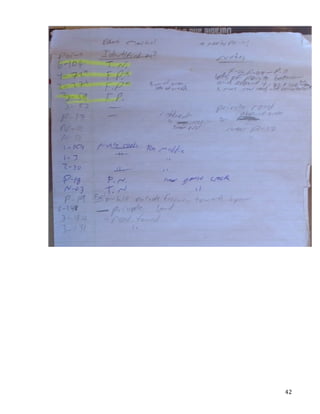

![53

corrgram(admdata[,2:6],

order=TRUE,

lower.panel=panel.shade,

upper.panel=panel.pie,

text.panel=panel.txt,

main="A.anserinus

Collinearity

Data")

corrgram(admdata[,2:6],

order=TRUE,

lower.panel=panel.ellipse,

upper.panel=panel.pts,

text.panel=panel.txt,

diag.panel=panel.minmax,

main="A.anserinus

Collinearity

Data")

####Model

Fitting:

Generalized

Linear

Model(glm)####

gc()

#clear

garbage

from

memmory

M2

=

glm(formula=pb~.,data=admdata)

summary(M2)

##Bioclim

only

takes

presence

values

bc=

bioclim(presvals)

pairs(bc)

##Predicting

GLM

pM2

=

predict(enviropredictors,

M2,

na.rm=TRUE)

plot(pM2)

title(main

=

"Generalized

Linear

Model

Raw

Value")

summary(M2)

####

Train/Test

data

####

##get

training/testing

sets

of

data

from

admdata

head(admdata)

samp

=

sample(nrow(admdata),

round(0.75*nrow(admdata)))

traindata=admdata[samp,]

traindata=traindata[traindata[,1]

==

1,

2:7]

testdata=admdata[-‐samp,]

pres

=

admdata[admdata[,1]

==

1,

2:7]

absen

=

admdata[admdata[,1]

==

0,

2:7]

##AUC

could

be

biased

due

to

high

extent

=

high

AUC

values

(Lobo

et

al.

2008,

Jimenez-‐Valverde

2011)

##So,

get

rid

of

"spatial

sorting

bias"

via

"point-‐wise

distance

sampling"

nr=nrow(Pointsxy)

s=sample(nr,0.25*nr)

pres_train=Pointsxy[-‐s,]

pres_test=Pointsxy[s,]

nr=nrow(Absencexy)

s=sample(nr,0.25*nr)

back_train=Absencexy[-‐s,]

back_test=Absencexy[s,]

sb=ssb(pres_test,back_test,pres_train)

sb[,1]/sb[,2]

##Spacial

Sorting

Bias

(SSB)

=

0.326

(If

no

bias

SSB=1)

##Create

subsample

where

SSB

is

removed

i

=

pwdSample(pres_test,back_test,pres_train,

n=1,tr=0.1)

pres_test_pwd=pres_test[!is.na(i[,1]),]

back_test_pwd=back_test[na.omit(as.vector(i)),]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4f0642fe-ff34-400e-9d28-12ccf8090a4b-150407130702-conversion-gate01/85/MacholInternship5-53-320.jpg)

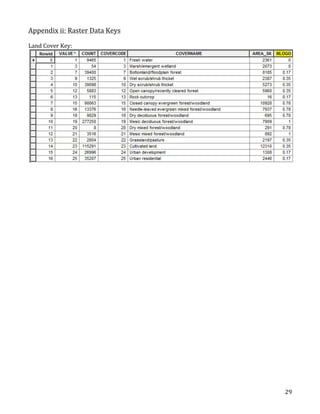

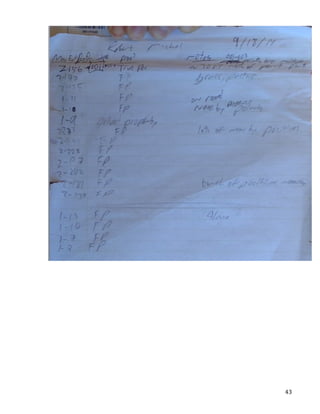

![54

sb2=ssb(pres_test_pwd,back_test_pwd,pres_train)

sb2[1]/sb2[2]

##SSB

=

0.999

-‐-‐

Much

Reduced!

###Visualize

train/test

points

r=raster(enviropredictors,1)

plot(!is.na(r),col=c('white','light

grey'),legend=FALSE)

points(back_train,

pch='-‐',

cex=0.5,

col=

'yellow')

points(back_test,

pch='-‐',

cex=0.5,

col=

'black')

points(pres_train,

pch=

'+'

,

col=

'green'

)

points(pres_test,

pch=

'+'

,

col=

'blue'

)

##########

MaxEnt

##############

##Note!

Most

widely

used

SDM

algorythm

(according

to

Hijmans

and

Elith)

##limit

extent:

ext

=

extent(-‐144.6,

-‐113.7,

41.5,

42.3)

##Uses

"jar"

package

-‐

http://www.cs.princeton.edu/~schapire/maxent/

jar

<-‐

paste(system.file(package="dismo"),

"/java/maxent.jar",

sep='')

jar

if

(file.exists(jar)){

xm=maxent(enviropredictors,pres_train,

ext

=

ext)

plot(xm)

}

else

{

cat('cannot

run

this

example

because

maent

is

not

available')

plot(1)

}

response(xm)

e

=

evaluate(pres_test,back_test,xm,enviropredictors)

e

#AUC=0.7712

px=predict(enviropredictors,xm,progress='')

par(mfrow=c(1,2))

plot(px,main='MaxEnt,

Raw

Values')

trpx=threshold(e,'spec_sens')

plot(px>trpx,

main='Presence/Absence')

points(pres_train,

pch='+')

##Write

raw

data

as

raster

writeRaster(px,file="RawMaxExt.tif",overwrite=TRUE)

##Write

pres/abs

model

as

raster

MaxExtPresAbs=(px>trpx)

writeRaster(MaxExtPresAbs,file="MaxExtPresAbs.tif",overwrite=TRUE)

####

Max

Ext

Evaluation

####

e=evaluate(testdata[testdata==1,],

testdata[testdata==0,],

xm)

e

plot(e,'ROC')

##AUC

value

=

.827

(guess

@

.5)

##k-‐fold

-‐

do

it

agin

k

times

pres

=

admdata[admdata[,1]

==

1,

2:7]

absen

=

admdata[admdata[,1]

==

0,

2:7]

k

=

100

##I

am

going

to

run

this

10

times

group

=

kfold(pres,

k)

##presence

only,

which

is

good

becuase

the

absence

falls

very

close

##absence

is

supposed

to

be

used

to

test

model](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4f0642fe-ff34-400e-9d28-12ccf8090a4b-150407130702-conversion-gate01/85/MacholInternship5-54-320.jpg)

![55

group[1:100]

unique(group)

e=list()

for

(i

in

1:k)

{

train=pres[group!=i,]

test=pres[group==i,]

xm=maxent(enviropredictors,pres_train)

e[[i]]=evaluate(p=test,a=absen,xm)

}

e

##AUC

values

for

sensitivity(true

positive

rate)

##

and

specificity

(true

negaitive

rate)

##With

SSB:

evaluate(xm,

p=pres_test,a=back_test,x=enviropredictors)

##AUC

with

=0.719

(0.5

is

guess)

##SSB

removed

evaluate(xm,

p=pres_test_pwd,

a=back_test_pwd,

x=enviropredictors)

##AUC

SSB

reduced

=

0.621

##These

numbers

changed

each

time

you

run

new

model,

so...

##Hist

for

AUC

with

SSB

removed

k

=

100

##I

am

going

to

run

this

100

times

group

=

kfold(pres,

k)

##presence

only,

which

is

good

becuase

the

absence

falls

very

close

##absence

is

supposed

to

be

used

to

test

model

group[1:100]

unique(group)

e=list()

for

(i

in

1:k)

{

j

=

pwdSample(pres_test,back_test,pres_train,

n=1,tr=0.1)

pres_test_pwd=pres_test[!is.na(j[,1]),]

back_test_pwd=back_test[na.omit(as.vector(j)),]

sb2=ssb(pres_test_pwd,back_test_pwd,pres_train)

xm=maxent(enviropredictors,pres_train)

e[[i]]=evaluate(xm,

p=pres_test,a=back_test,x=enviropredictors)

}

e

##AUC

values

for

sensitivity(true

positive

rate)

##

and

specificity

(true

negaitive

rate)

auc

=

sapply(e,function(x){slot(x,'auc')}

)

auc

par(mar=c(1,1,1,0))

par(oma=c(1,1,0.5,0))

par(mfrow=c(1,1))

hist(auc,

main

=

'MaxExt

AUC

with

SSB',

sub

=

'mean

=

0.796')

meanauc

=

mean(auc)

#0.745

abline(v

=

meanauc,

col

=

"blue",

lwd

=

2)

text(meanauc,

0

,

round(meanauc,

4))

text(meanauc,

6

,

"mean

=

",

cex

=

1)

TprTnr

=

sapply(e,function(x){

x@t[which.max(x@TPR

+

x@TNR)]

}

)

TprTnr

par(mar=c(1,1,1,0))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4f0642fe-ff34-400e-9d28-12ccf8090a4b-150407130702-conversion-gate01/85/MacholInternship5-55-320.jpg)