M browne mag design

•

0 likes•274 views

Enrique, a 17-year-old Honduran boy, is found badly injured in the small Mexican village of Las Anonas after falling from a freight train. The villagers take him in and care for his wounds. Enrique tells them that he is traveling north through Mexico to find his mother who left Honduras 11 years ago to work in the United States. Despite facing many dangers along the way like robberies, beatings, and deportations, Enrique is determined to continue his journey to be reunited with his mother. The villagers offer Enrique food, money, and clothes to help him on his way to getting medical help.

Report

Share

Report

Share

Download to read offline

Recommended

Recommended

More Related Content

Recently uploaded

Recently uploaded (20)

2º CALIGRAFIAgggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg.doc

2º CALIGRAFIAgggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg.doc

Digital/Computer Paintings as a Modern- day Igbo Artists’ vehicle for creatin...

Digital/Computer Paintings as a Modern- day Igbo Artists’ vehicle for creatin...

2137ad - Characters that live in Merindol and are at the center of main stories

2137ad - Characters that live in Merindol and are at the center of main stories

European Cybersecurity Skills Framework Role Profiles.pdf

European Cybersecurity Skills Framework Role Profiles.pdf

The Legacy of Breton In A New Age by Master Terrance Lindall

The Legacy of Breton In A New Age by Master Terrance Lindall

2137ad Merindol Colony Interiors where refugee try to build a seemengly norm...

2137ad Merindol Colony Interiors where refugee try to build a seemengly norm...

Tackling Poverty in Nigeria, by growing Art-based SMEs

Tackling Poverty in Nigeria, by growing Art-based SMEs

Winning Shots from Siena International Photography Awards 2015

Winning Shots from Siena International Photography Awards 2015

Nagpur_❤️Call Girl Starting Price Rs 12K ( 7737669865 ) Free Home and Hotel D...

Nagpur_❤️Call Girl Starting Price Rs 12K ( 7737669865 ) Free Home and Hotel D...

THE SYNERGY BETWEEN TRADITIONAL “ULI” BODY PAINTING SYMBOLS AND DIGITAL ART.

THE SYNERGY BETWEEN TRADITIONAL “ULI” BODY PAINTING SYMBOLS AND DIGITAL ART.

Caffeinated Pitch Bible- developed by Claire Wilson

Caffeinated Pitch Bible- developed by Claire Wilson

thGAP - BAbyss in Moderno!! Transgenic Human Germline Alternatives Project

thGAP - BAbyss in Moderno!! Transgenic Human Germline Alternatives Project

Featured

Featured (20)

Product Design Trends in 2024 | Teenage Engineerings

Product Design Trends in 2024 | Teenage Engineerings

How Race, Age and Gender Shape Attitudes Towards Mental Health

How Race, Age and Gender Shape Attitudes Towards Mental Health

AI Trends in Creative Operations 2024 by Artwork Flow.pdf

AI Trends in Creative Operations 2024 by Artwork Flow.pdf

Content Methodology: A Best Practices Report (Webinar)

Content Methodology: A Best Practices Report (Webinar)

How to Prepare For a Successful Job Search for 2024

How to Prepare For a Successful Job Search for 2024

Social Media Marketing Trends 2024 // The Global Indie Insights

Social Media Marketing Trends 2024 // The Global Indie Insights

Trends In Paid Search: Navigating The Digital Landscape In 2024

Trends In Paid Search: Navigating The Digital Landscape In 2024

5 Public speaking tips from TED - Visualized summary

5 Public speaking tips from TED - Visualized summary

Google's Just Not That Into You: Understanding Core Updates & Search Intent

Google's Just Not That Into You: Understanding Core Updates & Search Intent

The six step guide to practical project management

The six step guide to practical project management

Beginners Guide to TikTok for Search - Rachel Pearson - We are Tilt __ Bright...

Beginners Guide to TikTok for Search - Rachel Pearson - We are Tilt __ Bright...

M browne mag design

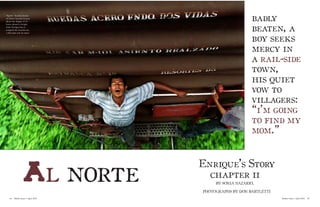

- 1. “Spent” Nearly exhausted, Santo Antonio Gamay shows the fatigue of 15 hours aboard a freight train. Enrique has attempted the treacherous 1,564-mile trek six times. badly beaten, a boy seeks mercy in a rail-side town, his quiet vow to villagers: “i’m going to find my mom.” Al norte Enrique’s Story Mother Jones // April 2010 45 44 Mother Jones // April 2010 chapter ii BY SONIA NAZARIO, PHOTOGRAPHS BY DON BARTLETTI

- 2. The day’s work is done at Las Anonas, a rail-side hamlet of 36 families in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, when a field hand, Sirenio Gomez Fuentes, sees a startling sight: a battered and bleeding boy, naked except for his undershorts. It is Enrique. He limps forward on bare feet, stumbling one way, then another. His right shin is gashed. His upper lip is split. The left side of his face is swollen. He is crying. Near this spot in Las Anonas, Mexico, Sirenio Gomez Fuentes was startled to see Enrique, bleeding and nearly naked, stumbling toward him. Gomez hears him whisper, “Give me water, please.” The knot of apprehension in Sirenio Gomez melts into pity. He runs into his thatched hut, fills a cup and gives it to Enrique. “Do you have a pair of pants?” Enrique asks. Gomez dashes back inside and fetches some. There are holes in the crotch and the knees, but they will do. Then, with kindness, Gomez directs Enrique to Carlos Carrasco, the mayor of Las Anonas. Whatever has happened, maybe he can help. Enrique hobbles down a dirt road into the heart of the little town. He encounters a man on a horse. Could he help him find the mayor? “That’s me,” the man says. He stops and stares. “Did you fall from the train?” Again, Enrique begins to cry. Mayor Carrasco dismounts. He takes Enrique’s arm and guides him to his home, next to the town church. “Mom!” he shouts. “There’s a poor kid out here! He’s all beaten up.” Carrasco drags a wooden pew out of the church, pulls it into the shade of a tamarind tree and helps Enrique onto it. Lesbia Sibaja, the mayor’s mother, puts a pot of water on to boil and sprinkles in salt and herbs to clean his wounds. She brings Enrique a bowl of hot broth, filled with bits of meat and potatoes. He spoons the brown liquid into his mouth, careful not to touch his broken teeth. He cannot chew. Townspeople come to see. They stand in a circle. “Is he alive?” asks Gloria Luis, a stout woman with long black hair. “Why don’t you go home? Wouldn’t that be better?” “I am going to find my mom,” Enrique says, quietly. He is 17. It is March 24, 2000. Eleven years before, his mother had left home in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, to work in the United States. She did not come back, and now he is riding freight trains up through Mexico to find her. Gloria Luis looks at Enrique and thinks about her own children. She earns little; most people in Las Anonas make 30 pesos a day, roughly $3, working the fields. She digs into a pocket and presses 10 pesos into Enrique’s hand. Several other women open his hand, adding 5 or 10 pesos each. Mayor Carrasco gives Enrique a shirt and shoes. He has cared for injured immigrants before. Some have died. Giving Enrique clothing will be futile, Carrasco Lesbia Sibaja, the mayor’s mother, puts a pot of water on to boil and sprinkles in salt and herbs to clean his wounds. She brings Enrique a bowl of hot broth, filled with bits of meat and potatoes. He spoons the brown liquid into his mouth, careful not to touch his broken teeth. He cannot chew. Townspeople come to see. They stand in a circle. “Is he alive?” asks Gloria Luis, a stout woman with long black hair. “Why don’t you go home? Wouldn’t that be better?” “I am going to find my mom,” Enrique says, quietly. He is 17. It is March 24, 2000. Eleven years before, his mother had left home in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, to work in the United States. She did not come back, and now he is riding freight trains up through Mexico to find her. Gloria Luis looks at Enrique and thinks about her own children. She earns little; most people in Las Anonas make 30 pesos a day, roughly $3, working the fields. She digs into a pocket and presses 10 pesos into Enrique’s “He limps forward on bare feet, stumbling one way, then another. His right shin is gashed. His upper lip is split. The left side of his face is swollen. He is crying.” “Heavy hands” Grupo Beta undercover police agents subdue a youth near an immigration checkpoint in Chiapas, Mexico. Enrique has faced deportation on each one of his attempts to reach the United States. “End of the line” 13-year-old David Velasquez peers out of a jail cell crowded with other train stowaways captured in Chiapas, Mexico. Next stop, a deportation to the Guatemala border. Enrique and other Centrail American migrants face robbings and beatings upon their confinement and deportation. 46 Mother Jones // April 2010

- 3. hand. Several other women open his hand, adding 5 or 10 pesos each. Mayor Carraco gives Enrique a shirt and shoes. He has cared for injured immigrants before. Some have died. Giving Enrique clothing will be futile, Carrasco thinks, if he can’t find someone with a car who can get the boy to medical help. Adan Diaz Ruiz, mayor of San Pedro Tapanatepec, the county seat, happens by in his pickup. Carrasco begs a favor: Take this kid to a doctor. Diaz balks. He is miffed. “This is what they get for doing this journey,” he says. Enrique cannot pay for any treatment. Why, Diaz wonders, do these Central American governments send us all their problems? Looking at the small, soft-spoken boy lying on the bench, he reminds himself that a live migrant is better than a dead one. In 18 months, Diaz has had to bury eight of them, nearly all mutilated by the trains. Already today, he has been told to expect the body of yet another, in his late 30s. Sending this boy to a doctor would cost the county $60. Burying him in a common grave would cost three times as much. First, Diaz would have to pay someone to dig the grave, then someone to handle the paperwork, then someone to stand guard while Enrique’s unclaimed body is displayed on the steamy patio of the San Pedro Tapanatepec cemetery for 72 hours, as required by law. All the while, people visiting the graves of their loved ones would complain about the smell of another rotting migrant. “We will help you,” he tells Enrique finally. He turns him over to his driver, Ricardo Diaz Aguilar. Inside the mayor’s pickup, Enrique sobs, but this time with relief. He says to the driver, “I thought I was going to die.” An officer of the judicial police approaches in a white pickup. Enrique cranks down his window. Instantly, he recoils. He recognizes both the officer and the truck. The officer, too, seems startled. For a moment, the officer and the mayor’s driver discuss the new dead immigrant. Quickly, the policeman pulls away. “That guy robbed me yesterday,” Enrique says. The policeman and a partner had taken 100 pesos from him and three other ABOVE: “ready to jump” Honduran migrants prepare to jump as the train approaches an immigration checkpoint in Chiapas, Mexico. Several had been arrested here before and deported 200 miles back to the Guatemala border. Continued on page 133... Mother Jones // April 2010 49 48 Mother Jones // April 2010 ABOVE: “Soaring” “the pilgrim train” Mexican authorities call freights crowded with migrants “El Tren Peregrino” or “The Pilgrim Train”. Treated as law-breaking foreigners in Mexico, undocumented Central Americans have made cargo trains a major migratory route north to the U.S. border. migrants at gunpoint in Chahuites, about five miles south. The mayor’s driver is not surprised. The judicial police, he says, routinely stop trains to rob and beat immigrants. The judiciales--the Agencia Federal de Investigacion--deny it. In San Pedro Tapanatepec, the driver finds the last clinic still open that night. Perseverance When Enrique’s mother left, he was a child. Six months ago, the first time he set out to find her, he was still a callow kid. Now he is a veteran of what has become a perilous children’s pilgrimage to the north. Every year, experts say, an estimated 48,000 youngsters like Enrique from Central America and Mexico enter the United States illegally and without either of their parents. Many come looking for their mothers. They travel any way they can, and thousands ride the tops and sides of freight trains. They leap on and off rolling train cars. They forage for food and water. Bandits prey on them. So do street gangsters deported from Los Angeles, who have made the train tops their new turf. None of the youngsters have proper papers. Many are caught by the Mexican police or by la migra, the Mexican immigration authorities, who take them south to Guatemala. Most try again. Like many others, Enrique has made several attempts. The first: He set out from Honduras with a friend, Jose del Carmen Bustamante. They remember traveling 31 days and about 1,000 miles through Guatemala into the state of Veracruz in central Mexico, where la migra captured them on top of a train and sent them back to Guatemala on what migrants call el bus de lagrimas, the bus of tears. These buses make as many as eight runs a day, deporting more than 100,000 unhappy passengers every year. The second: Enrique journeyed by himself. Five days and 150 miles into Mexico, he committed the mistake of falling asleep on top of a train with his shoes off. Police stopped the train near the town of Tonala to hunt for migrants, and Enrique had to jump off. Barefoot, he could not run far. He hid overnight in some grass, then was captured and put on the bus back to Guatemala. Thirteen-year-old David Velasquez, left, and Robert Gaytan, 17, wait to be jailed after they were caught in Tapachula, Mexico.