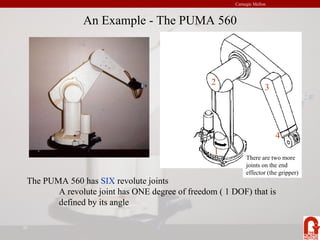

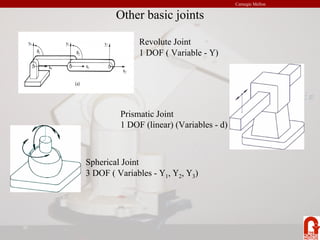

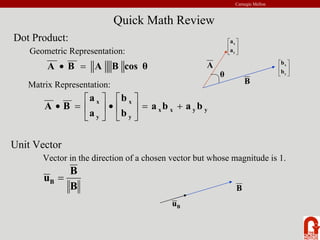

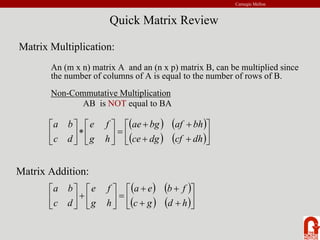

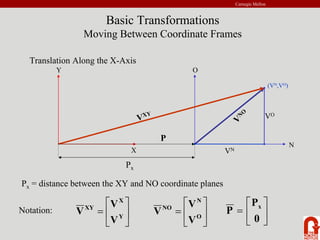

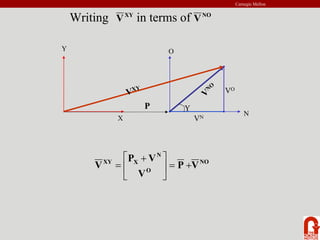

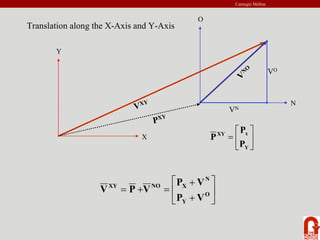

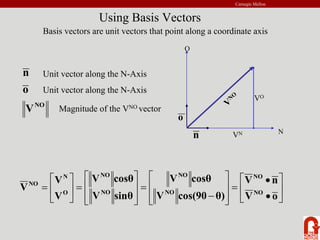

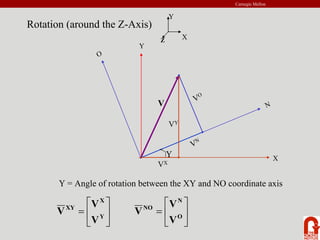

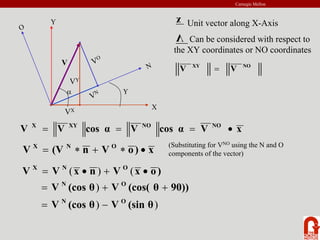

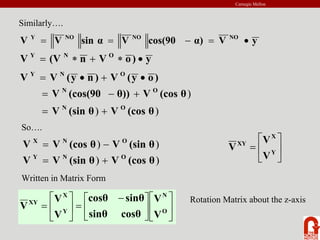

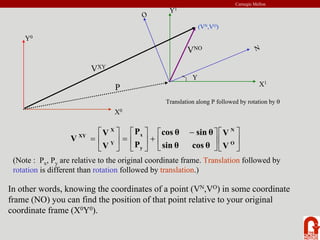

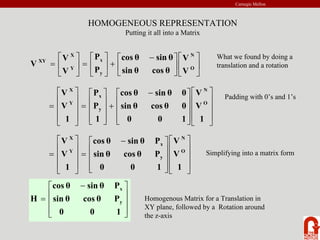

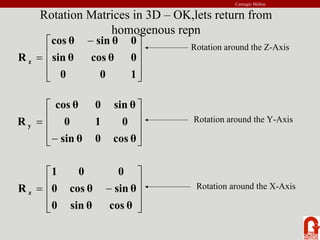

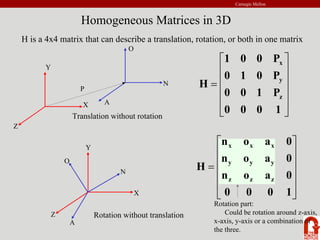

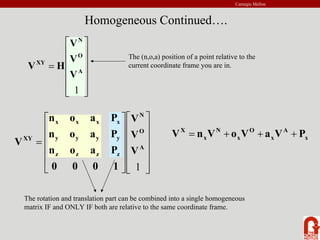

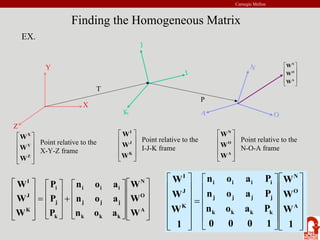

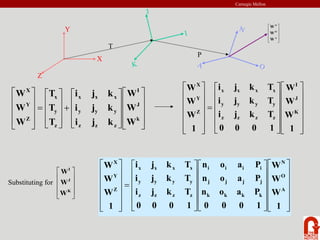

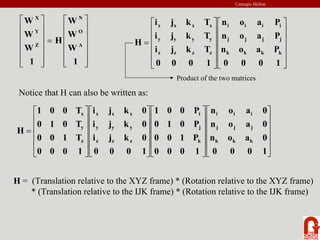

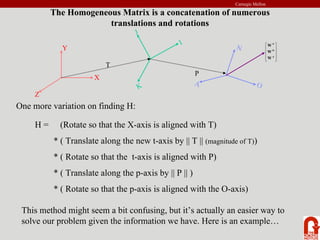

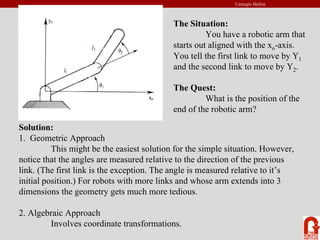

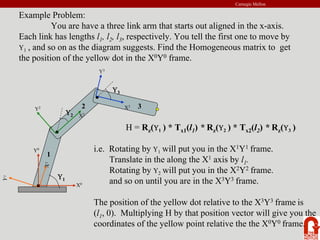

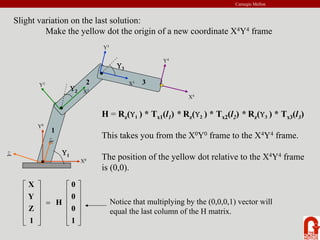

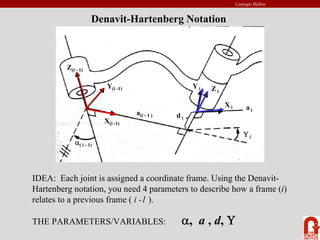

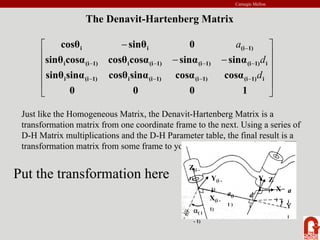

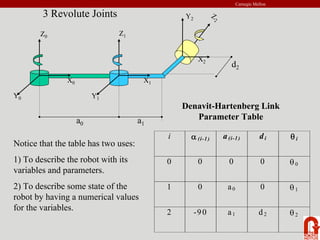

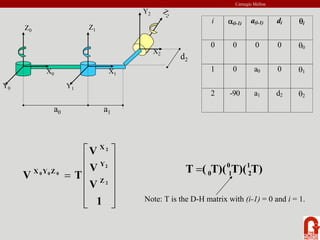

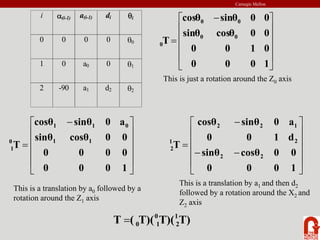

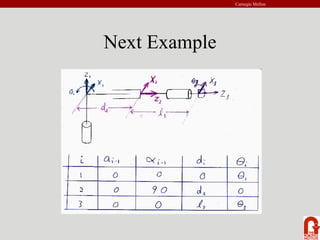

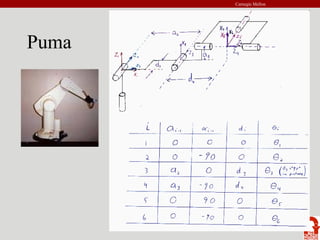

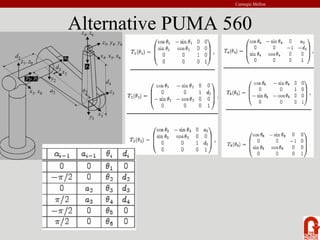

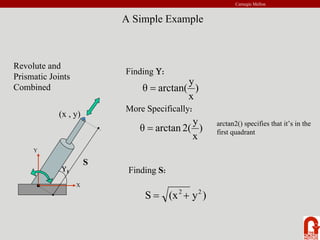

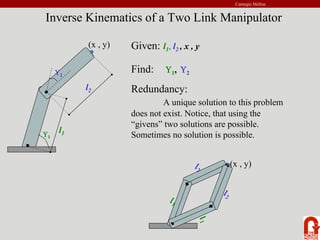

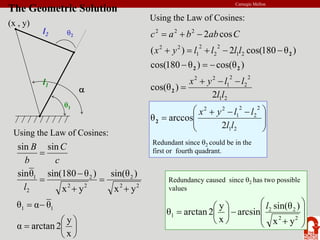

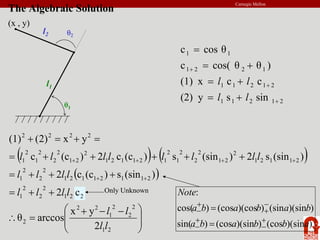

The document provides an introduction to robot kinematics. It discusses the PUMA 560 robot and its six revolute joints. It also covers other basic robot joints like spherical, revolute, and prismatic joints. The document explains forward and inverse kinematics. It provides a math review of topics like dot products, matrices, and unit vectors. It then covers basic transformations between coordinate frames using translation and rotation matrices. Homogeneous transformations are introduced to represent rotations and translations with a single 4x4 matrix.