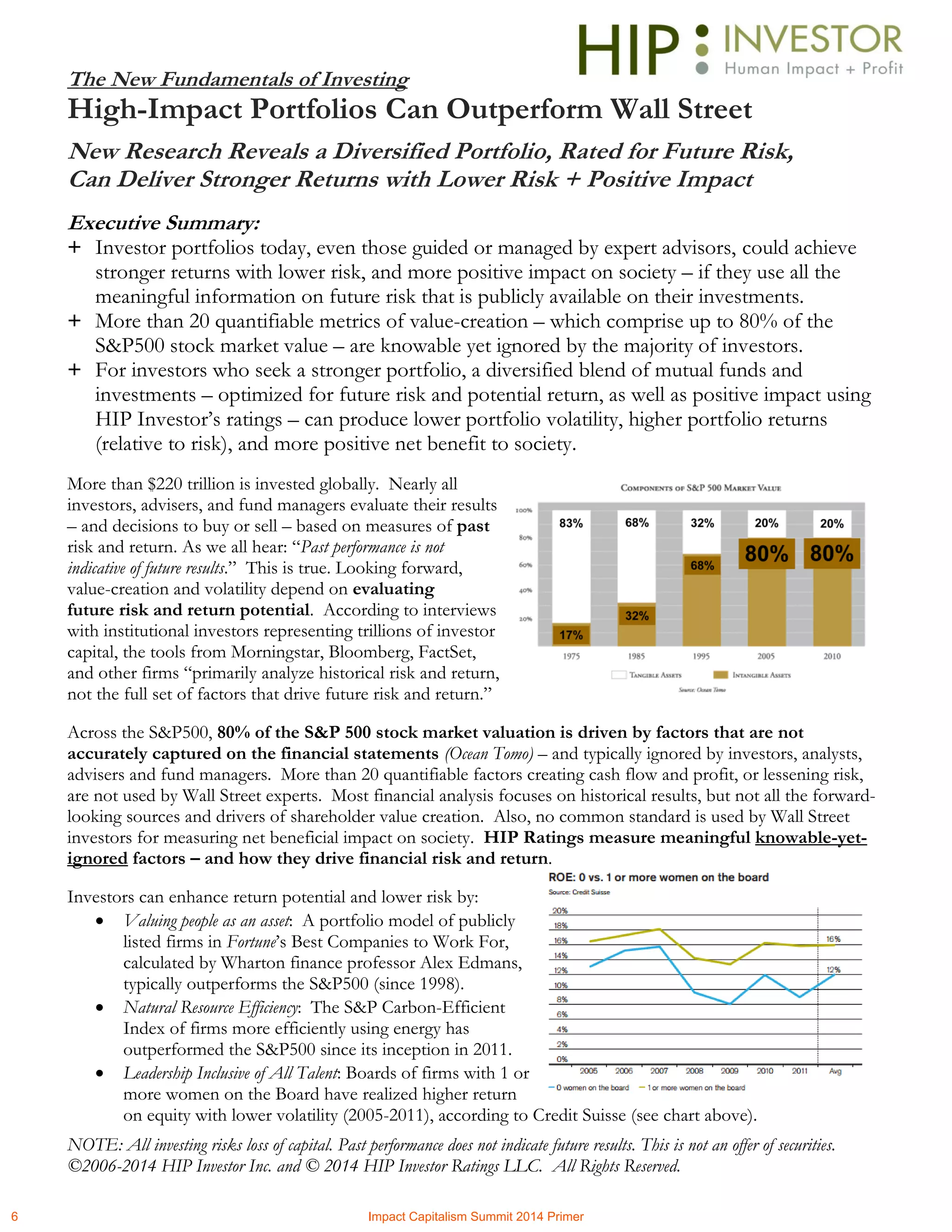

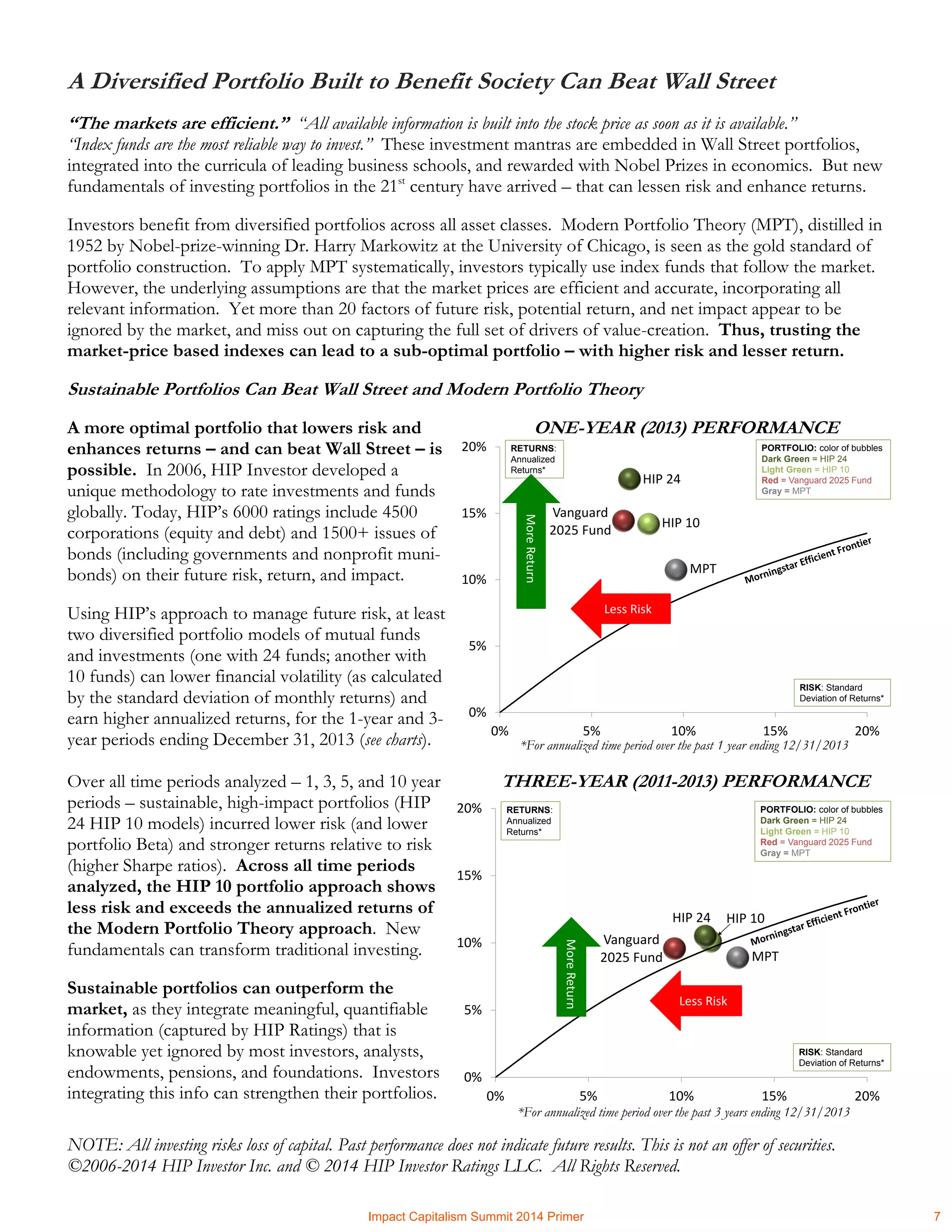

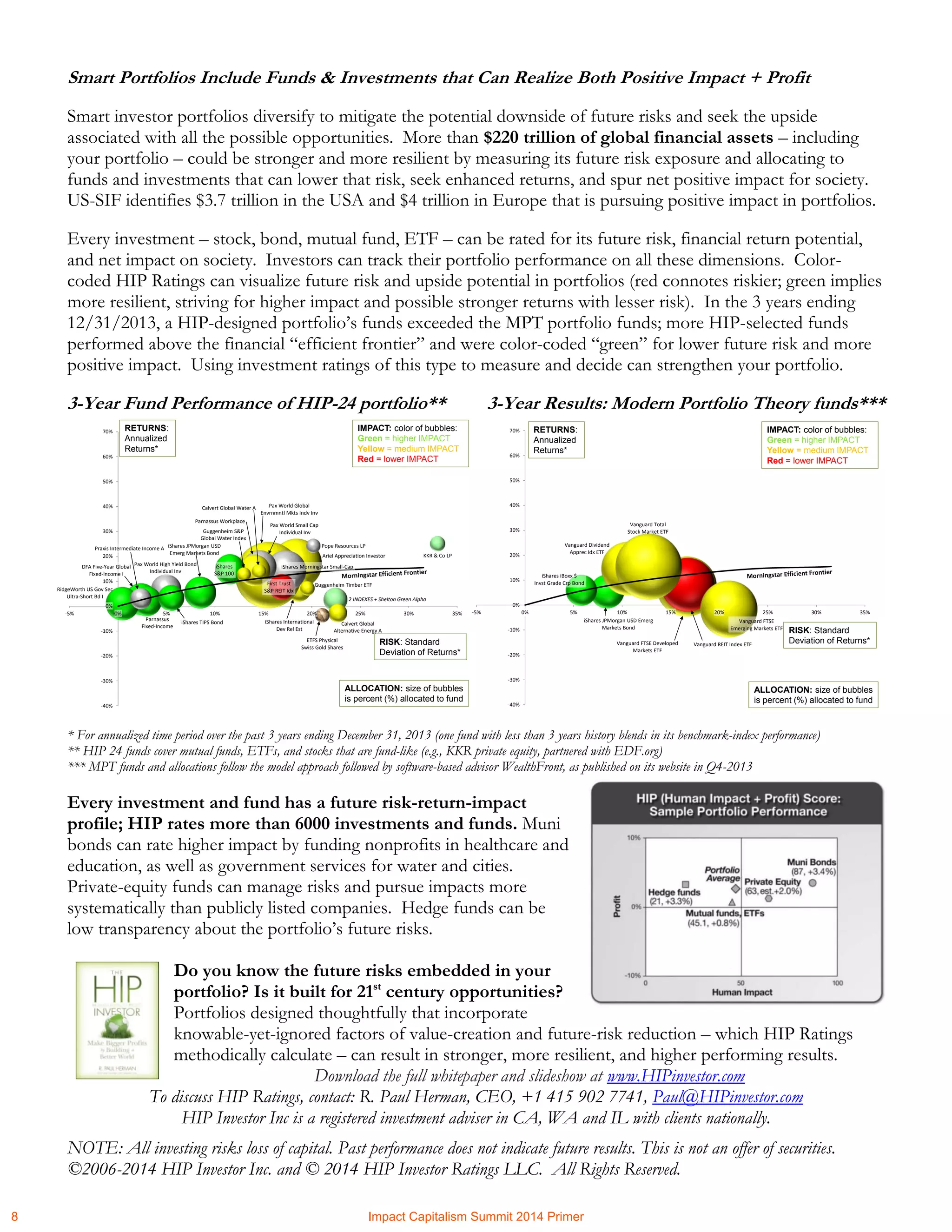

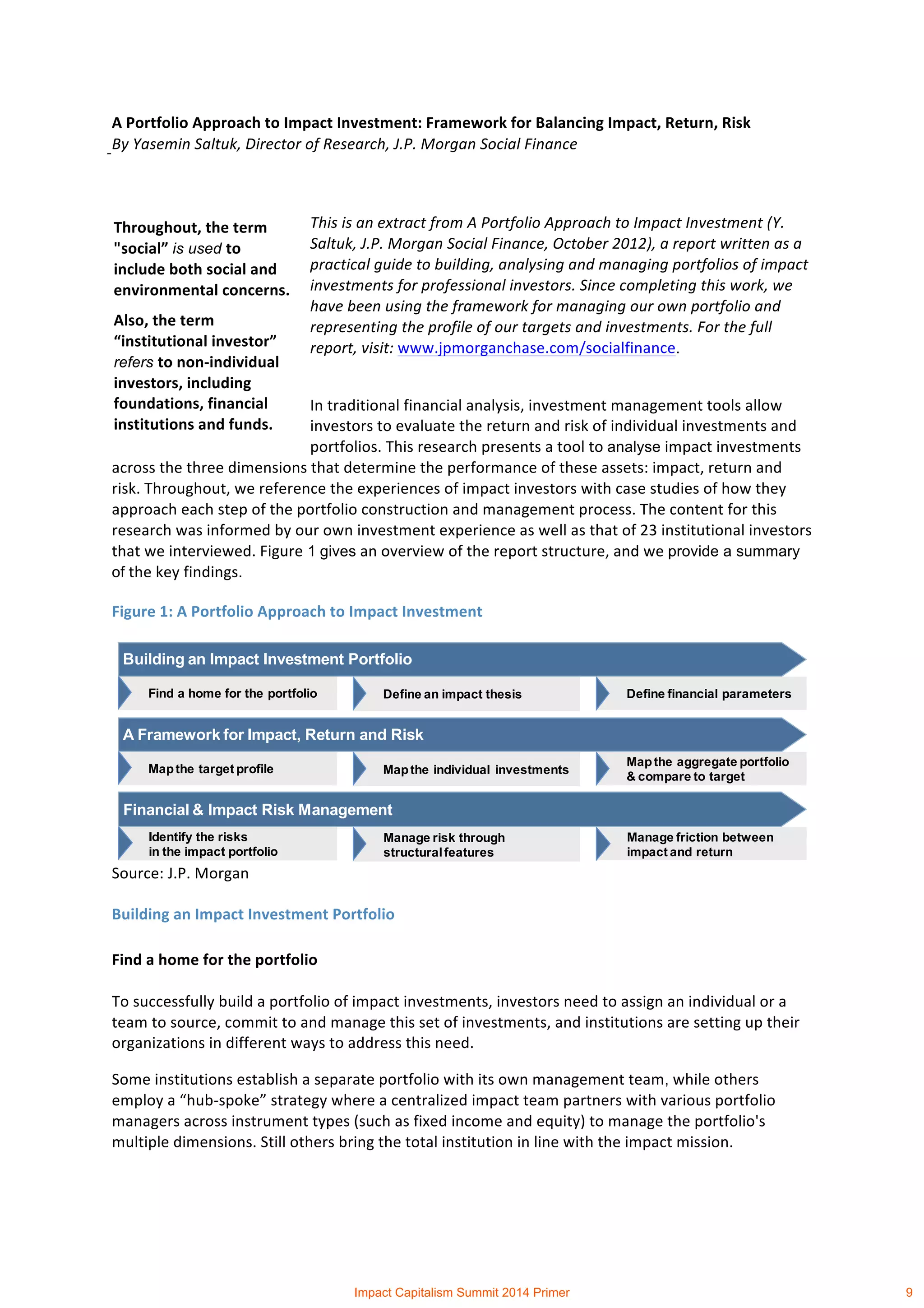

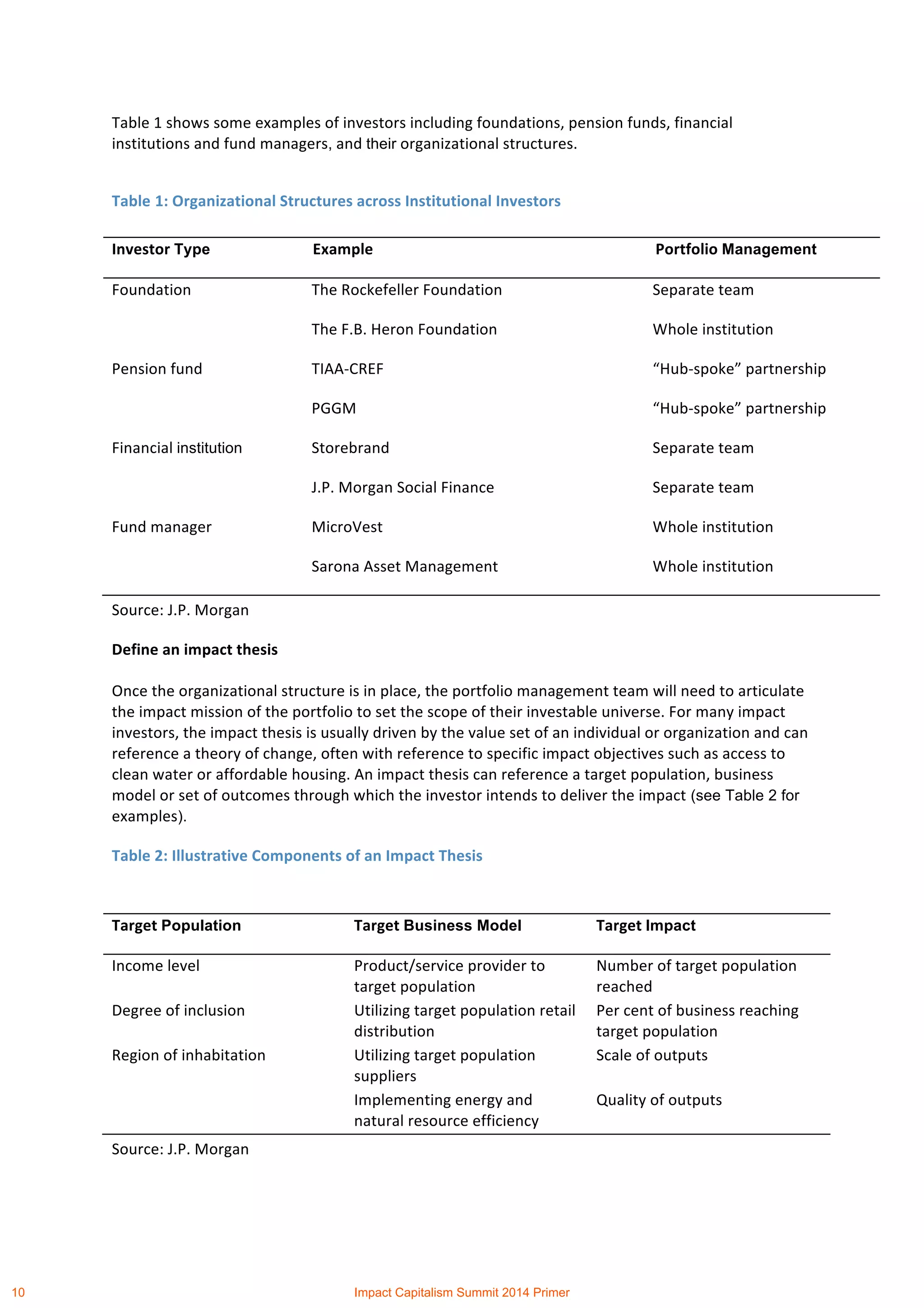

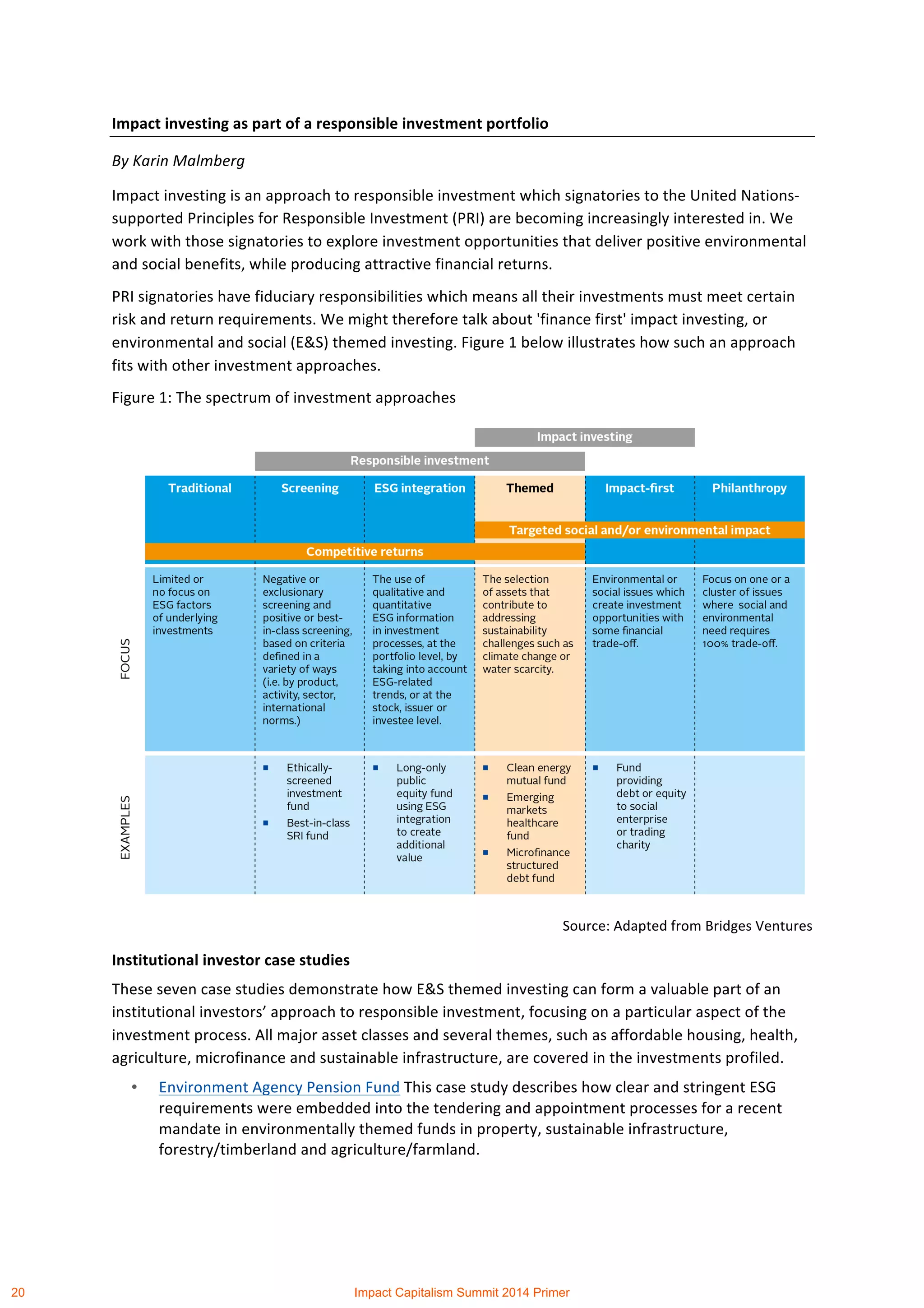

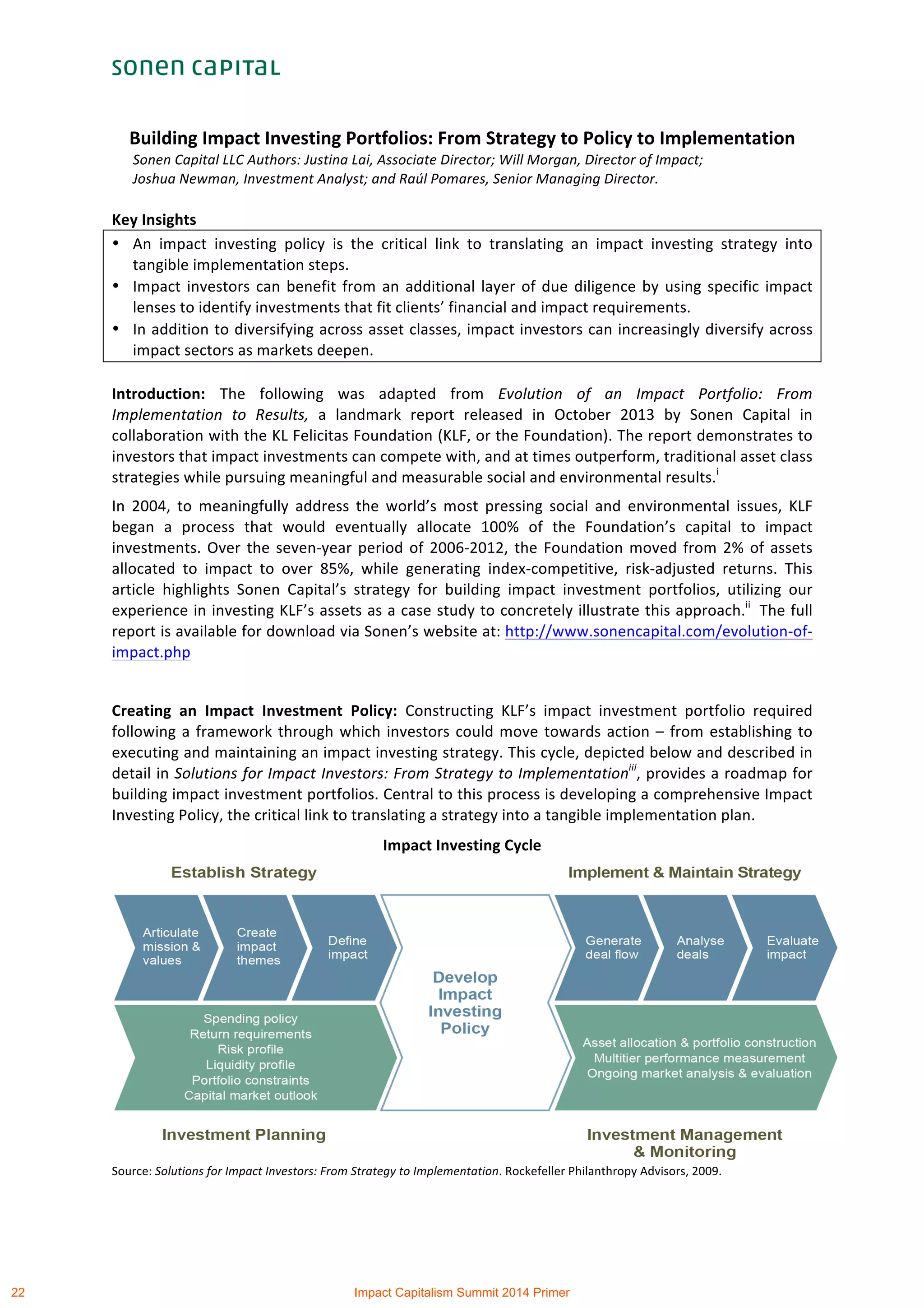

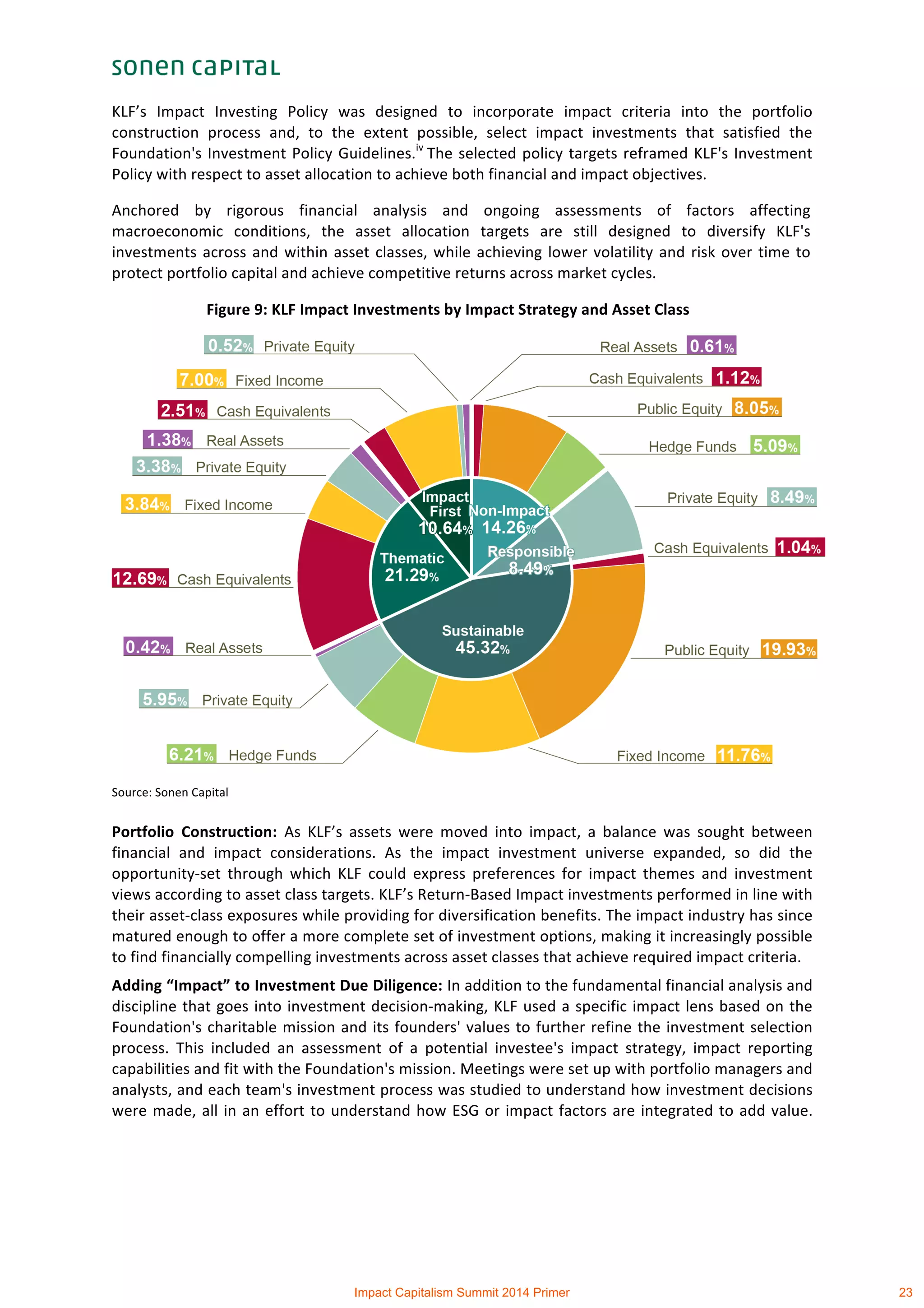

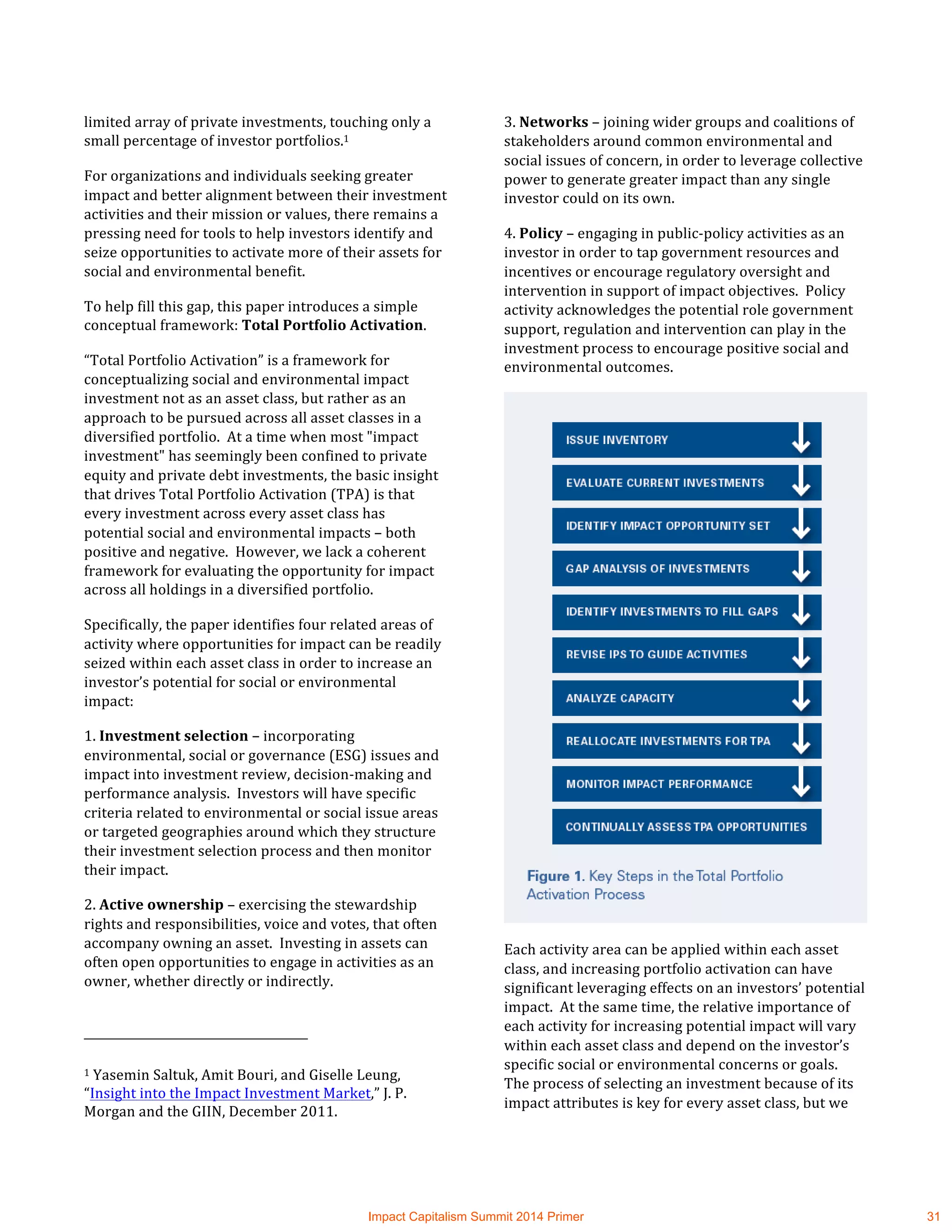

The document is a primer for the 2014 Impact Capitalism Summit. It discusses how impact investing portfolios can outperform traditional investing by incorporating environmental, social and governance factors that are knowable but often ignored. It provides evidence that portfolios focused on high-impact companies can achieve lower risk and higher returns than benchmarks. The primer includes articles making the case for impact investing across different asset classes as part of a responsible investment strategy. It also profiles the summit organizers, Watershed Capital Group, and their experience assisting companies with sustainability solutions.