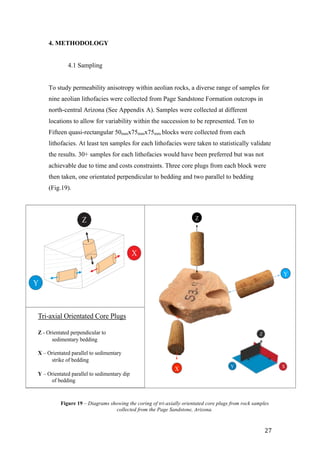

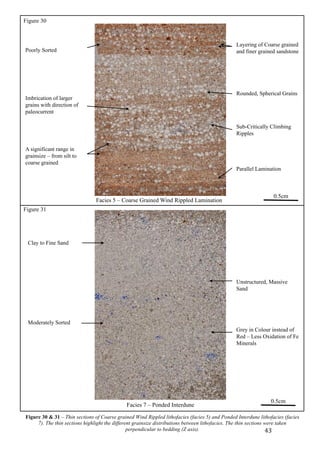

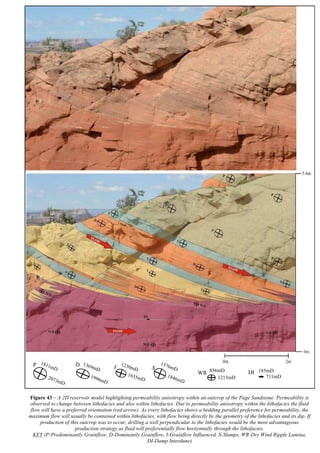

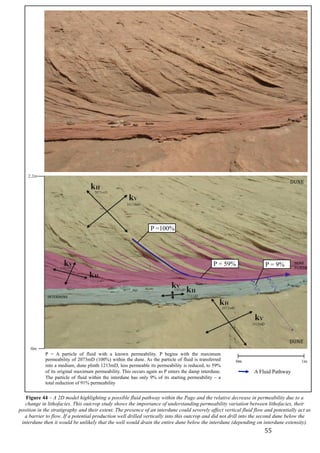

This document summarizes a study of permeability heterogeneity in an aeolian sandstone reservoir. Fieldwork identified 9 lithofacies in the Page Sandstone formation in Arizona based on sedimentary structures. Core samples were taken from each lithofacies and tested for petrophysical properties including permeability and porosity. Permeability was found to vary over 3 orders of magnitude between lithofacies and architectural elements. Permeability was also found to be anisotropic, with higher values parallel versus perpendicular to bedding. The permeability heterogeneity observed has implications for reservoir modeling and production from aeolian reservoirs that were previously considered homogeneous.

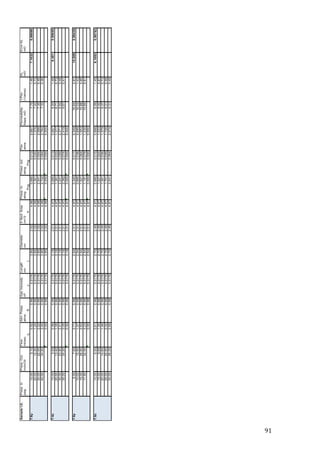

![9

Table&1.!Age!and!elevation!of!floodplain!and!terrace1gra

River!from!Glen!Canyon!Dam!to!Badger!Rapids,!a!25!m

Refer!to!locations!of!separate!older!terrace1gravel!depos

Map$unit Age

Qf Holocene

Qg1

Young!and!intermediate!terrace1gravel!

Floodplain!deposits

Older!terrace1gravel!deposits

Holocene

Qg2 Holocene

Qg3 Holocene

Qg4 Holocene!and!Pleistocene(?)

Qg5 Holocene!and!Pleistocene(?)

Qg6 Holocene(?)!and!Pleistocene

Qg7 Pleistocene

Qg8 Pleistocene

Qg9 Pleistocene

Qg9a Pleistocene

Qg10 Pleistocene

Qg11 Pleistocene

Qg12 Pleistocene

Qg13 Pleistocene

Qg14 Pleistocene

Qg15 Pleistocene

Qg16 Pleistocene!and!Pliocene(?)

Qg17 Pleistocene!and!Pliocene(?)

Qg18 Pleistocene!and!Pliocene(?)

112°00'

111°00'

37°00'

36°30'

Marble

Canyon

Vermilion

Cliffs!Lodge

Cliff

Dwellers

Lodge

Lees!Ferry

LeChee

Copper!Mine

Page

Kaibito

RAINBOW

PLATEAU

PARIA PLATEAU

Ferry Swale

Vermilion

Cliffs

STRIP

ARIZONA

MARBLE PLATEAU

NAVAJO&&INDIAN

RESERVATIONHouse Rock Valley

VERMILION&CLIFFS

NATIONAL&MONUMENT

Glen

Canyon

Dam

GLEN&CANYON

NRA

89

89A

98

LeChee Rock

Tse Esgizii Butte

Cummings

Mesa

Kaibito

Creek

Creek

Navajo

C

olorado2River

Paria2River

KAIBITO

PLATEAU

COW1SPRINGS

SYNCLINE

PRESTON1MESA

ANTICLINE

TUBA1CITY

SYNCLINE

ECHO1CLIFFS

MONOCLINE

EMINENCE

BREAK1FAULT

FENCE

FAULT

LIMESTONE

RIDGE

ANTICLINE

PARIA1PLATEAU1SYNCLINE

LAST

CHANCE

ANTICLINE

RED1LAKE

MONOCLINE

KAIBITO

SYNCLINE

F

F

F

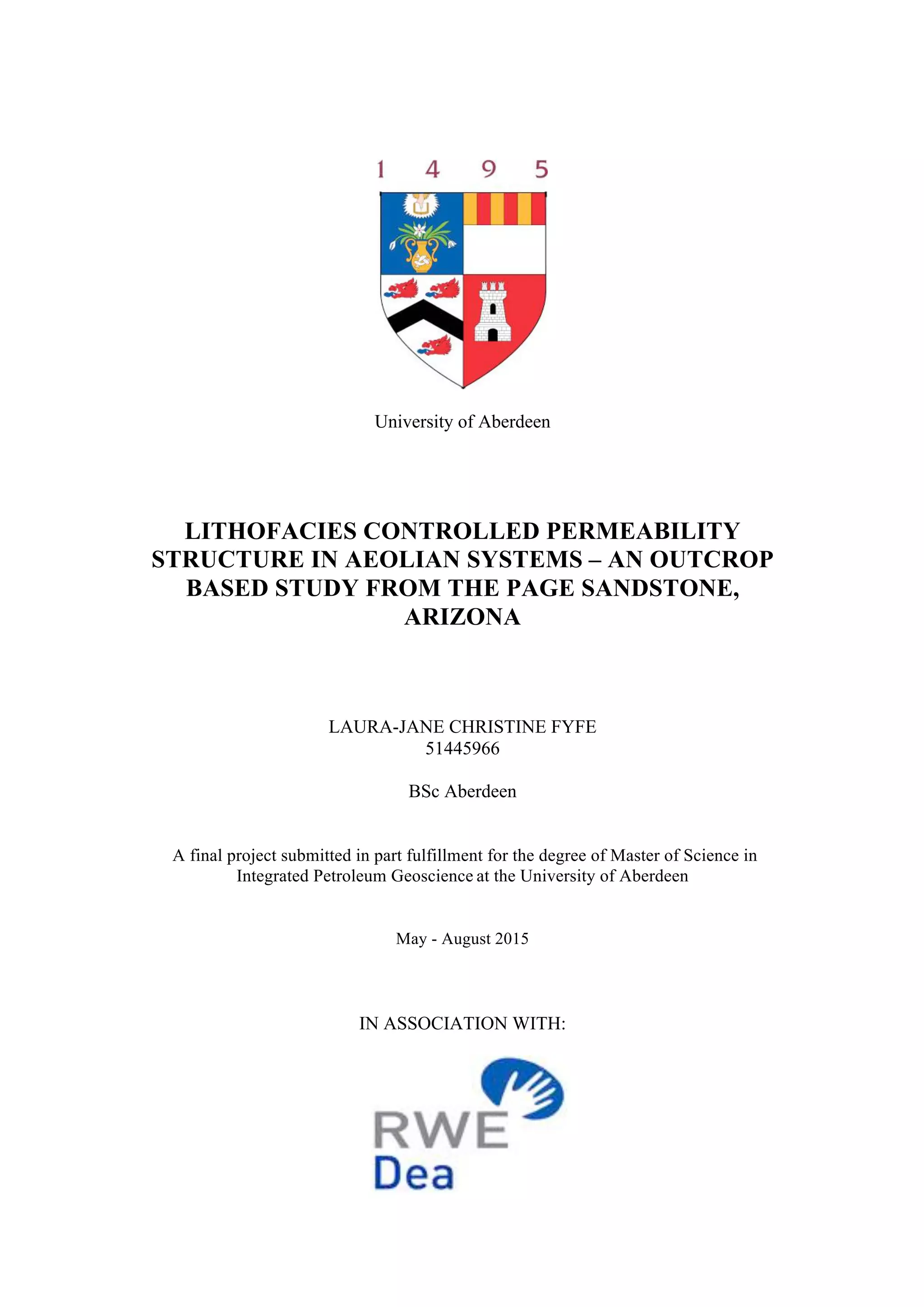

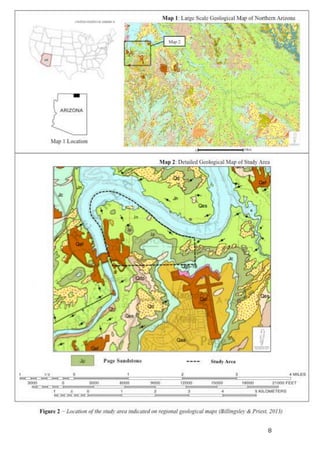

Figure&1.!Map!of!the!Glen!Canyon!Dam!30’!x!60’!quadrangle!showing!cultural!and!physiographic!features!as!well!as!major!geologic!structures.

Boxes!define!area!of!maps!in!figure!2.

Cedar

Mountain

Echo

Cliffs

GRAND&CANYON

NATIONAL&PARK

Bitter!Springs

89

White

Mesa

2B

2A

Geologic Map of the Glen Ca

Ph

Pc

Pe

Ms

Mr

Ms

co

cp

Jn

Jk

Jks

Jm

cs

mu

ms

mlm

Pkh

Pkf

Pt

Jcu

Jc

JpJcj

Je

Jr

Jms

Km

Kd

Qg3 Qa3

Qv Qtr Ql

Qg4

Qa4 Qg5-18

Tgs

QdpQdQes QdlQsQaf Qf Qg1QdluQdb Qdm Qa2Qg2Qa1 Qps Qae

Pliocene

Upper

Triassic

Lower!Triassic

Middle(?)!and

Lower!Triassic

Cisuralian

Middle!Jurassic

Lower!Jurassic

Glen

Canyon

Group

San

Rafael

Group

Holocene

Pleistocene

QUATERNARY

JURASSIC

TRIASSIC

PERMIAN

CORRELATION&OF&MAP&UNITS

SURFICIAL&DEPOSITS

SEDIMENTARY&ROCKS

TERTIARY

Upper

Cretaceous

Unconformity

Unconformity

Unconformity

Unconformity

Unconformity

Unconformity

Unconformity

Unconformity

Unconformity

Unconformity

Unconformity

Unconformity

Unconformity

Unconformity

Unconformity

Upper!and!Lower

Mississippian

MISSISSIPPIAN

CRETACEOUS

Upper,!Middle!and

Lower!Pennsylvanian

and!Upper

Mississippian

Upper!Mississippian

PENNSYLVANIAN

Supai

Group

Miocene

Upper!Jurassic

National P

U.S. Department of the Interior

U.S. Geological Survey

Qg14

Qg1

Qg13

Qg5Qg6

Qg5

Qg6

Qg5

BA

111°37'30''

36°52'30''

111°30'

35

35

?

M

M ?

F

F

F

oo

Qf

Qs

Qaf

Qd

Qes

Qdp

Qdb

Qdl

Jk

Kd

Km

Je

Jks

Jc

Jms

Jr

Jn

Jp

Jcj

Jcu

Jm

co

cp

cs

mu

ms

mlm

Pkh

Pkf

Pt

Pc

Ph

Pe

ms

Ms

Mr

Qa4

Qg4

Tgs

Qae

Qps

Qa3

Qg3

Ql

Qg5-18

Qtr

Qv

Qg2

Qa2

Qa1

Qg1

Qdlu

Qdm

LIST&OF&MAP&UNITS

[Some!map!units!are!too!small!to!distinguish!unit!identification!by!color.!These!units!are!labeled!

where!possible`!all!units!are!attributed!in!the!geodatabase]

SURFICIAL&DEPOSITS

Artificial&fill&and&quarries&(Holocene)

StreamMchannel&deposits&(Holocene)

Floodplain&deposits&(Holocene)

Sand&sheet&deposits&(Holocene)

Dune&sand&and&sand&sheet&deposits,&undivided&(Holocene)

Linear&dune&deposits&(Holocene)

Parabolic&dune&deposits&(Holocene)

Barchan&dune&deposits&(Holocene)

Mixed&dune&deposits&(Holocene)

Linear&dune&and&sand&sheet&deposits,&undivided&(Holocene)

Young&terraceMgravel&deposits&(Holocene)

Young&alluvial&fan&deposits&(Holocene)

Intermediate&terraceMgravel&deposits&(Holocene)

Intermediate&alluvial&fan&deposits&(Holocene)

Ponded&sediments&(Holocene)

Mixed&alluvium&and&eolian&deposits&(Holocene)

Old&terraceMgravel&deposits&(Holocene)

Old&alluvial&fan&deposits&(Holocene)

ValleyMfill&deposits&(Holocene&and&Pleistocene(?))

Talus&and&rockMfall&deposits&(Holocene&and&Pleistocene(?))

Landslide&deposits&(Holocene&and&Pleistocene)

Older&terraceMgravel&deposits&(Pleistocene)

Older&alluvial&fan&deposits&(Pleistocene&and&Pliocene(?))

Oldest&terraceMgravel&deposits,&undivided&(Pleistocene&and&Pliocene(?))

Gravel&and&sedimentary&deposits&(Pliocene(?)&or&Miocene(?))

SEDIMENTARY&ROCKS

Mancos&Shale&(Upper&Cretaceous)

Dakota&Sandstone&(Upper&Cretaceous)

Morrison&Formation&(Upper&Jurassic)

Salt&Wash&Member

San&Rafael&Group&(Middle&Jurassic)

Romana&Sandstone

Entrada&Sandstone

Carmel&Formation,&undivided

Paria&River&Member&and&Winsor&Member,&undivided

Judd&Hollow&Tongue&and&Page&Sandstone&Tongues,&undivided

Page&Sandstone

Glen&Canyon&Group&(Lower&Jurassic)

Navajo&Sandstone

Kayenta&Formation,&undivided

Springdale&Sandstone&Member

Moenave&Formation&and&Wingate&Sandstone,&undivided

Chinle&Formation&(Upper&Triassic)

Owl&Rock&Member&

Petrified&Forest&Member

Shinarump&Member

Moenkopi&Formation&(Middle(?)&and&Lower&Triassic)

Upper&red&member&(Middle(?)&and&Lower&Triassic)

Shnabkaib&Member&(Lower&Triassic)

Lower&red&member,&Virgin&Limestone&Member,&and&middle&red&member,&

undivided&(Lower&Triassic)

Kaibab&Formation&(Cisuralian)

Harrisburg&Member

Fossil&Mountain&Member

Toroweap&Formation,&undivided&(Cisuralian)

Coconino&Sandstone&(Cisuralian)

Hermit&Formation&(Cisuralian)

Supai&Group&(Cisuralian,&Pennsylvanian,&and&Upper&Mississippian)

Esplanade&Sandstone&(Cisuralian)

Wescogame&(Upper&Pennsylvanian),&Manakacha&(Middle&Pennsylvanian)&

and&Watahomigi&(Lower&Pennsylvanian&and&Upper&Mississippian)&FormaM

tions,&undivided

Surprise&Canyon&Formation&(Upper&Mississippian)

Redwall&Limestone,&undivided&(Upper&and&Lower&Mississippian)

EXPLANATION&OF&MAP&SYMBOLS

Contact—Contacts!between!all!alluvial!and!eolian!units!are!approximate!and!

arbitrary

Fault—Dashed!where!inferred`!dotted!where!concealed`!bar!and!ball!on!down1

thrown!side.!Showing!fault!offset!in!feet

Folds—Showing!trace!of!axial!surface!and!direction!of!plunge`!dotted!where!

location!is!concealed

Anticline

Plunging&anticline

Syncline

Plunging&syncline

Monocline

Strike&and&dip&of&beds

Inclined—Showing!dip!measured!in!the!field

Implied—Interpreted!from!aerial!photographs`!dip!not!determined

Strike&of&vertical&and&subvertical&joints—Interpreted!from!aerial!photographs`!

symbol!placed!where!joints!are!most!visible!on!aerial!photographs

Collapse&structure—Black!dot!shows!circular!collapse!structure!characterized!by!

strata!dipping!inward!toward!a!central!point.!Magenta!dot!shows!circular!

collapse!structure!characterized!by!strata!dipping!inward!toward!a!central!point!

and!brecciated!rock

Sinkhole

Mine&or&prospect

Fracture—Open!fracture!(0.5!to!3.5!m!wide)!without!offset

Offset&fracture—Open!fracture!(0.5!to!3.5!m!wide)!with!offset!(generally!less!than!

1.5!m

Prepared In Cooperation With The

National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and Navajo Nation

Scientific Investigati

Pamphlet

Figure 3 – Map 1 & 2 Geological Key (Billingsley & Priest, 2013)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/f48515b0-5b6a-4498-a67f-d9231feb738f-150827131335-lva1-app6892/85/FYFE_L_MSC_IPG_FINAL_PROJECT-20-320.jpg)

![71

Dickinson, W. R. (2004). Evolution of the North American cordillera. Annu. Rev.

Earth Planet. Sci., 32, p.13-45.

Douglas, S. W. (2010). The Jurassic Norphlet Formation of the Deep-Water Eastern

Gulf of Mexico: A. Waco: Masters thesis, Baylor University.

Farrell, N. J., Healey, D., & Taylor, C. W. (2014). Anisotropy of permeability in

faulted porous sandstones. Journal of Structural Geology , 63, 50-67.

Fossen, H., Schultz, R. A., & Torabi, A. (2011). Conditions and Implications for

Compaction Band Formation in the Navajo Sandstone, Utah. Journal of Structural

Geology , 33, 1477-1490.

Fryberger, S., & Hern, Y. C. (2014). A Geometric Approach to the Analysis of Global

Eolian Hydrocarbon Reservoirs. AAPG Rocky Mountain Section Meeting, (pp. 1-4).

Denver.

Gaud, M. N., Smith, G. A., & McKenna, S. A. (2012). Relating Small-Scale

Permeability Heterogeneity to Lithofacies Distribution. SEPM Special Publication

No. 80 , 55-66.

Goggin, D. J., Chandler, M. A., Kocurek, G., & Lake, L. W. (1992). Permeability

transects of eolian sands and their use in generating random permeability fields. SPE

Formation Evaluation, 7(01), p.7-16.

Goggin, D. J., Chandler, M. A., Kocurek, G. T., & Lake, L. W. (1988). Patterns of

permeability in eolian deposits: Page Sandstone (Jurassic), northeastern Arizona. SPE

Formation Evaluation, 3(02), p.297-306.

Google Earth 6.0. (2015). Page, Arizona 86040. 36 56'12.34'N 111 28'13.47W,

elevation 1220m. [Accessed 8 June 2015]. Available from:

http://www.google.com/earth/index.html.

Howell, J., & Mountney, N. (2001). Aeolian grain flow architecture: hard data for

reservoir models and implications for red bed sequence stratigraphy. Petroleum

Geoscience , 7, 51-56.

Kocurek, G. T. (2009). Desert aeolian systems In: Reading, H. G. (Ed.). 2009.

Sedimentary environments: processes, facies and stratigraphy. John Wiley & Sons.

p.125-152

Kocurek, G. (1999). The Aeolian Rock Record. In A. S. Goudie, I. Livingstone, & S.

Stokes (Eds.), Aeolian Environments, Sediments & Landforms (pp. 239-259).

Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Loope, D., Eisenberg, L., and Waiss, E. (2004). Navajo sand sea of near-equatorial

Pangea: Tropical westerlies, slumps, and giant stromatolites, in Nelson, E.P. and

Erslev, E.A., Field trips in the southern Rocky Mountains, USA: Geological Society of

America Field Guide 5, p.1–13.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/f48515b0-5b6a-4498-a67f-d9231feb738f-150827131335-lva1-app6892/85/FYFE_L_MSC_IPG_FINAL_PROJECT-82-320.jpg)

![72

Nordhal, K., & Ringrose, P. (2008). Identifying the Representative Elementary

Volume for Permeability in Heterolithic Deposits Using Numerical Rock Models.

Mathematical Geosciences , 40 (7), 753-771.

North, C. P., & Prosser, D. J. (1993). Characterization of fluvial and aeolian

reservoirs: problems and approaches. In C. P. North, & D. J. Prosser (Eds.),

Characterization of Fluvial and Aeolian Reservoirs (Vol. Special Publication No. 73,

pp. 1-6). Bath: The Geological Society.

Prosser, D. J., & Maskall, R. (1993). Permeability variation within aeolian sandstone:

A case study using core cut sub-parallel to slipface bedding, the Auk field, central

North Sea, UK. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 73(1), p.377-397.

Peterson, F. and G. N. Pipiringos. (1979). Stratigraphic relations of the Navajo

Sandstone to Middle Jurassic formations, southern Utah and northern Arizona. U.S.

Geological Survey Professional Paper 1035-B, p. 1–43.

Pierce, C., Howell, J., & Reike, H. (2014). Facies distribution within Aeolian sets

related to large scale 3D outcrop architecture: A virtual outcrop case study from the

Jurassic Page Sandstone, Arizona. Nottingham: British Sedimentological Research

Group AGM.

Ringrose, P., & Bentley, M. (2015). The Rock Model. In P. Ringrose, & M. Bentley,

Reservoir Model Design: A Practitioner's Guide (pp. 22-28). London: Springer.

Shell Corrib Development Team. (2015). Interview on An Industry Perspective On

Permeability Heterogeneity In Reservoir Modeling. Interviewed by Laura-Jane Fyfe

[Meeting] Shell Offices, Aberdeen, 27 July 2015, 09:00.

Stalkup, F. (1986). Permeability Variations Observed at the Faces of Crossbedded

Sandstone Outcrops. In L. W. Lake, & H. B. Carroll, Reservoir Characterization (pp.

141-181). London: Academic Press Inc.

Thorman, C. H. & Peterson, F. (2003). The Middle Jurassic Elko Orogeny - A Major

Tectonic Event in Nevada-Utah In Annual Meeting Expanded Abstracts, v.12, p.169-

174.

Torsaeter, O., & Abtahi, M. (2000). Experimental Reservoir Engineering: Laboratory

Work Book. Trondheim: Department of Petroleum Engineering and Applied

Geophysics, Norwegian University of Science and Technology.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/f48515b0-5b6a-4498-a67f-d9231feb738f-150827131335-lva1-app6892/85/FYFE_L_MSC_IPG_FINAL_PROJECT-83-320.jpg)