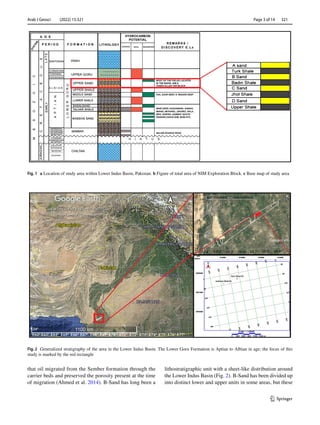

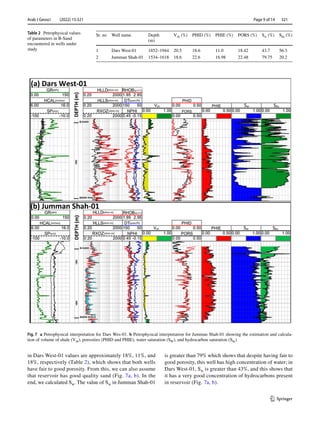

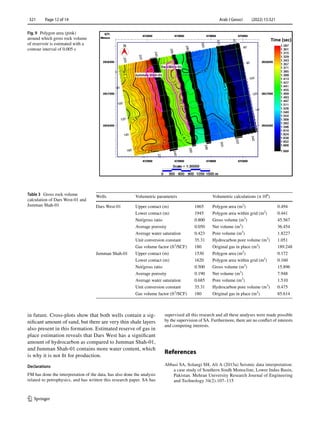

The document summarizes a study on lithology identification and gross rock volume (GRV) estimation of the B-Sand reservoir in the Lower Indus Basin of Pakistan. Well log and seismic data from two wells were analyzed using petrophysical and rock physics methods to identify the lithology and estimate reservoir properties. Cross-plots of elastic parameters helped differentiate lithologies including gas sand, oil sand, brine, and shale. GRV was calculated to estimate hydrocarbon volumes, showing the Dars West-01 well has more hydrocarbons and less water saturation than the Jumman Shah-01 well. The integrated analysis provides insights for accurate reservoir delineation, evaluation, and reserve estimation.