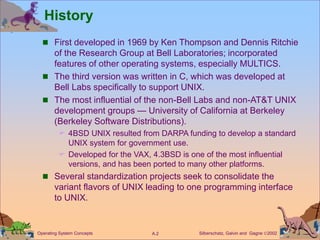

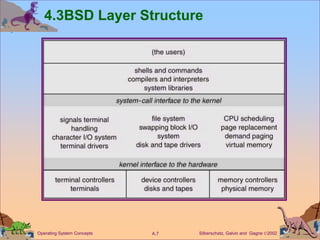

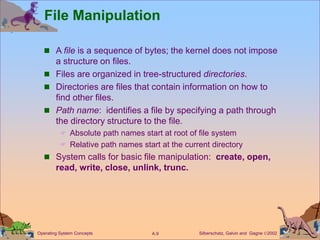

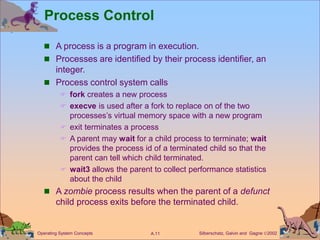

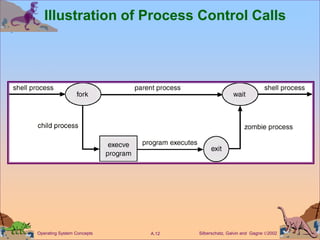

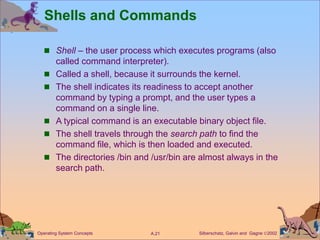

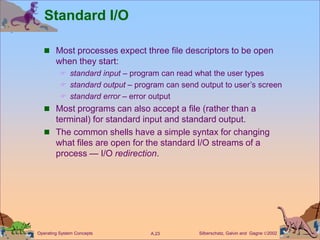

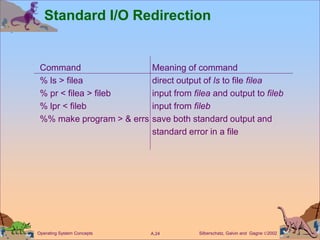

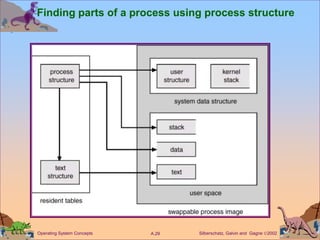

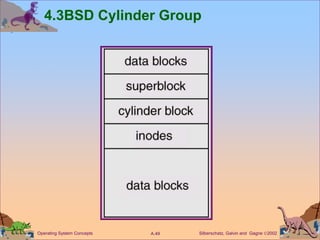

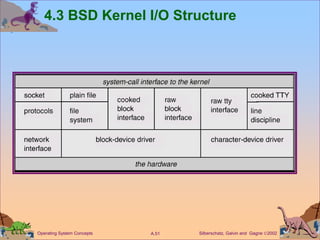

The document provides a comprehensive overview of the FreeBSD operating system, highlighting its history, design principles, user and programmer interfaces, process and memory management, file system, and I/O system. Key topics include the evolution of UNIX, system calls, process control mechanisms, and the interaction between user commands and the kernel. Additionally, it discusses advanced topics such as memory management strategies like paging and swapping, alongside various system programming interfaces and commands.