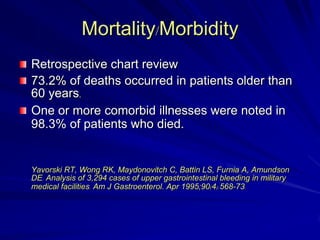

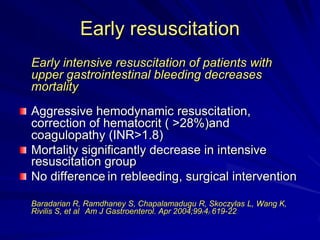

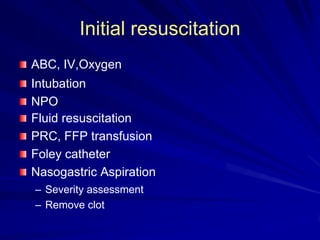

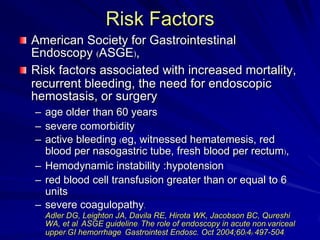

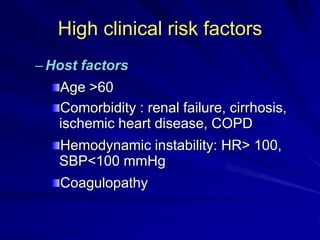

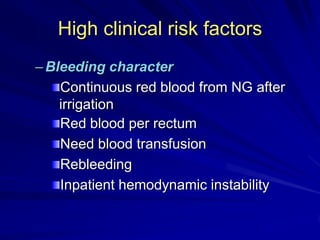

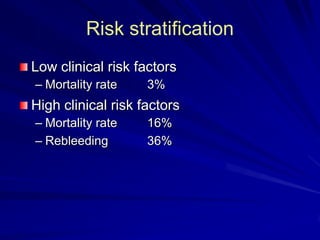

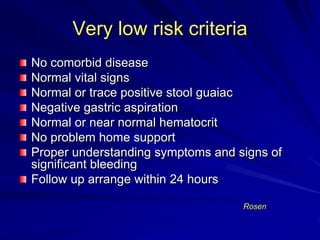

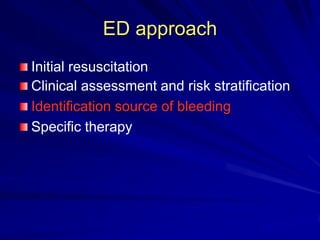

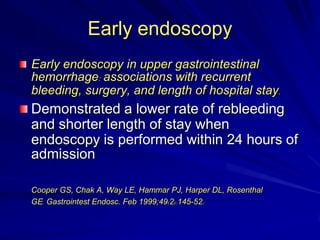

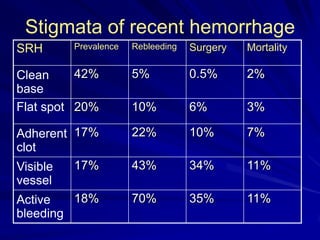

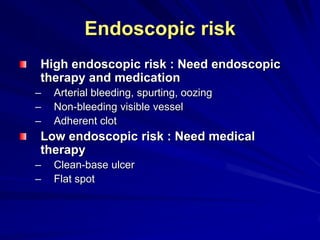

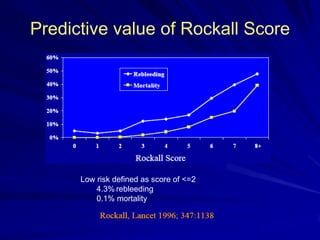

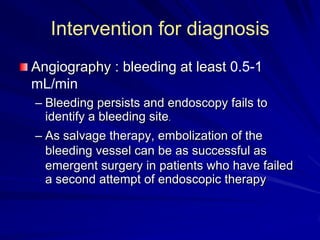

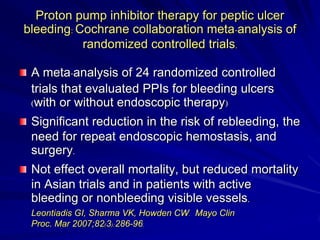

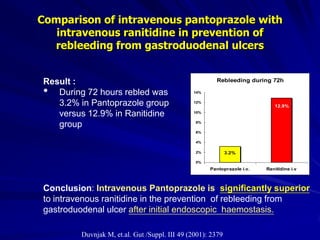

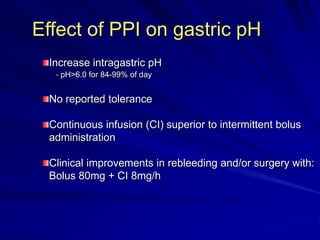

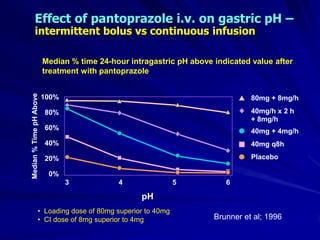

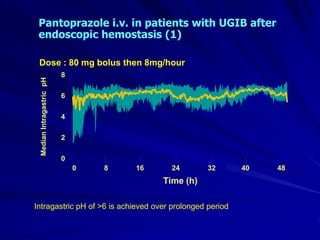

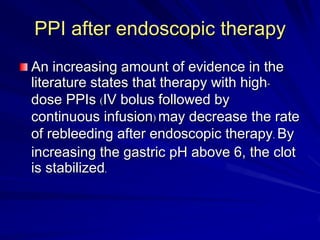

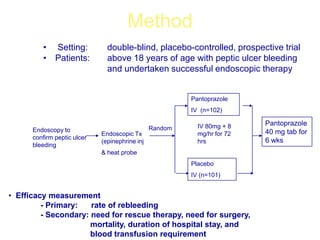

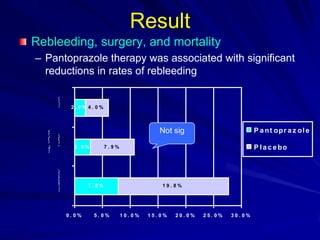

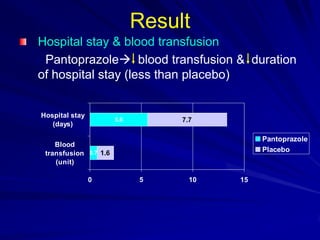

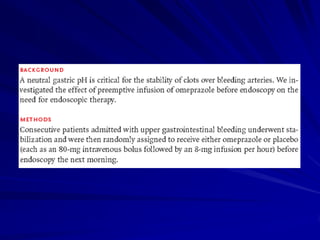

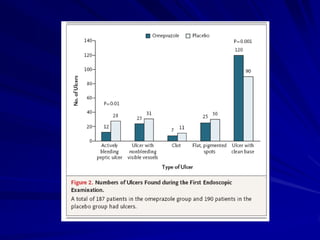

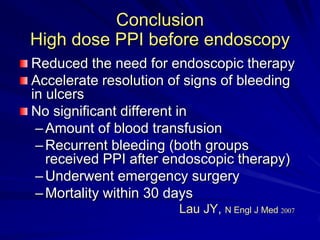

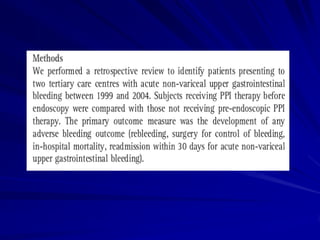

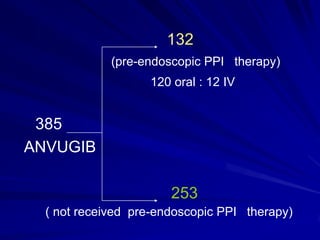

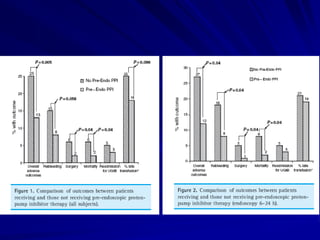

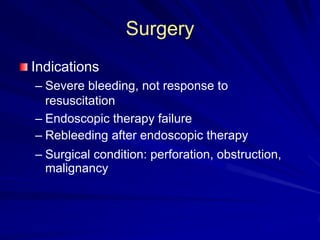

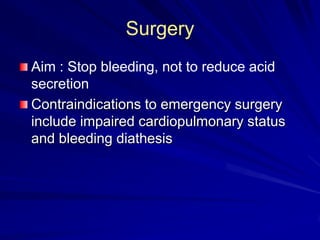

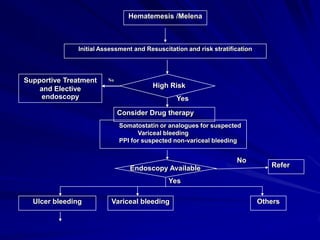

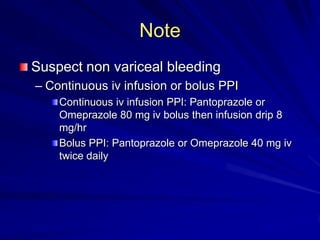

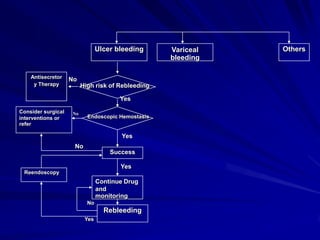

Initial resuscitation of patients with upper GI bleeding is critical and includes IV access, oxygen, fluid resuscitation, and blood product transfusion if needed. Early risk stratification evaluates factors like age, comorbidities, hemodynamic stability, and endoscopic findings to determine risk of rebleeding, need for intervention, and mortality. Source of bleeding is identified through endoscopy within 24 hours when possible. For low risk patients, medical therapy with PPIs is usually sufficient, while high risk patients may require endoscopic treatment or radiologic intervention. High dose PPIs, especially IV formulations, are effective in preventing rebleeding and shortening hospital stays when given before and after endoscopy. Surgery is reserved for