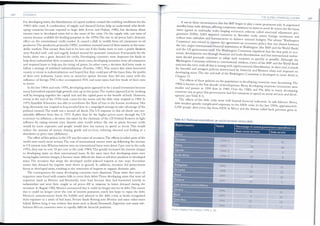

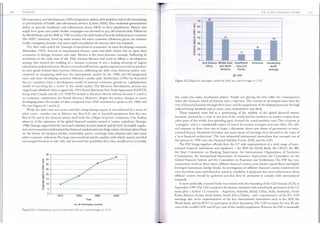

The document discusses the origins and structure of the post-World War II international monetary system established at Bretton Woods in 1944. The system centered around the US dollar being fixed to gold at $35 per ounce, and other currencies being fixed to the US dollar. It created the International Monetary Fund and World Bank to help manage the system and provide loans to countries. However, the system was undermined over time as more US dollars flooded out internationally than the US had in gold reserves, threatening the dollar-gold peg.