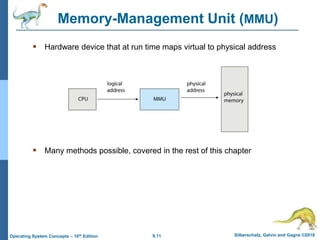

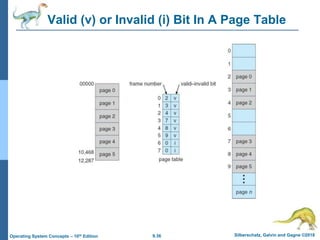

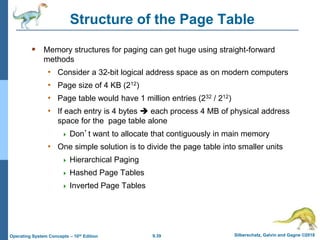

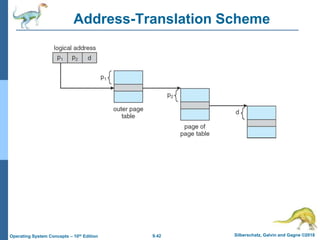

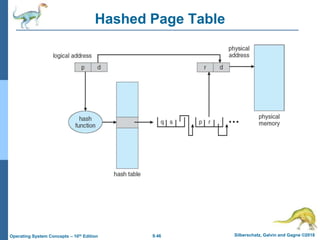

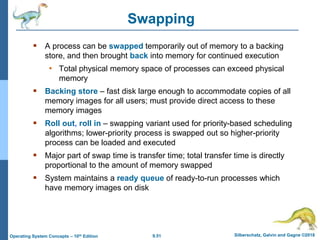

This document provides an overview of memory management techniques in operating systems. It discusses contiguous memory allocation, paging, page tables, and translation lookaside buffers (TLBs). Paging divides memory into fixed-size blocks called frames and logical memory into pages of the same size. A page table maps logical to physical addresses by storing the frame number for each page. TLBs improve performance by caching recent page table lookups. The document also covers memory protection, shared pages, and internal and external fragmentation in memory systems.