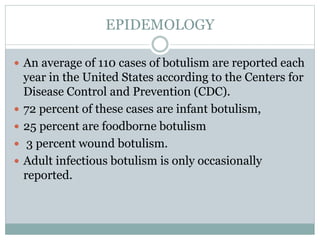

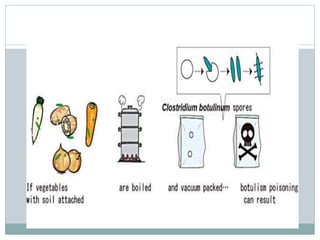

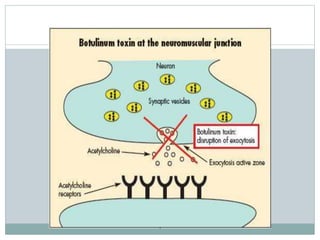

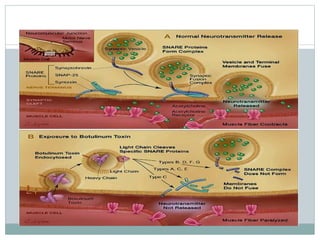

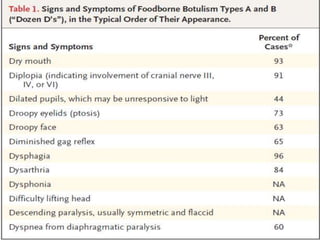

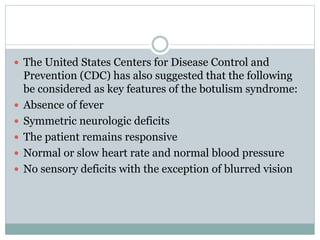

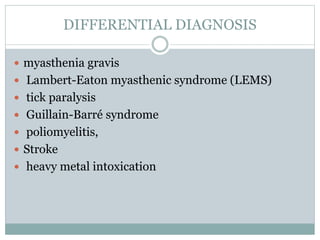

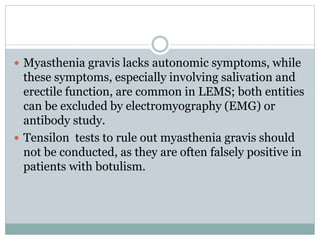

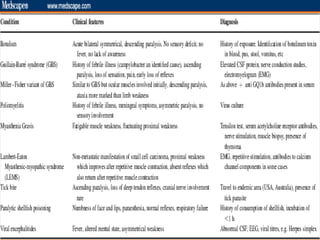

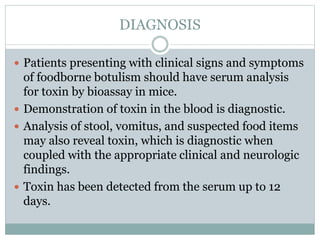

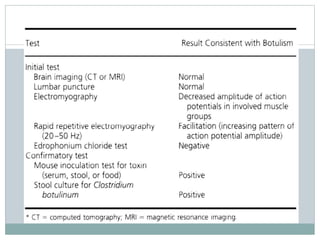

This document discusses botulism, a rare but potentially life-threatening illness caused by a toxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. It enters the body through foodborne, wound, or infant exposure and causes descending muscle weakness. Symptoms include blurred vision, drooping eyelids, slurred speech, and paralysis. Proper diagnosis requires detecting the toxin in blood or stool samples. Treatment involves antitoxin administration and supportive care such as ventilation. With prompt treatment, mortality rates are low at 5-8%; respiratory failure is the main cause of death.