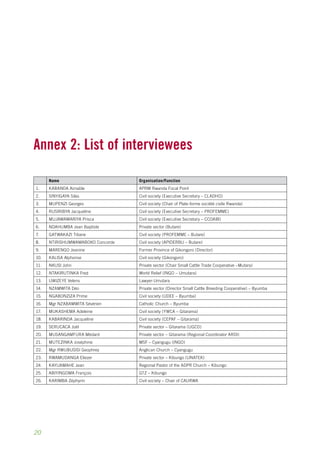

The document provides background information on Rwanda's participation in the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) process. It discusses how Rwanda was one of the first countries to sign up for the APRM in 2003. It then outlines the key stages of Rwanda's APRM process, including distributing a questionnaire, consultation meetings, drafting a country report, and a review mission. Finally, it notes that the process aimed to be inclusive of government and non-government stakeholders, but that civil society participation was limited.