Applications Of Mathematics In Models Artificial Neural Networks And Arts Mathematics And Society 1st Edition Vittorio Capecchi Auth

Applications Of Mathematics In Models Artificial Neural Networks And Arts Mathematics And Society 1st Edition Vittorio Capecchi Auth

Applications Of Mathematics In Models Artificial Neural Networks And Arts Mathematics And Society 1st Edition Vittorio Capecchi Auth

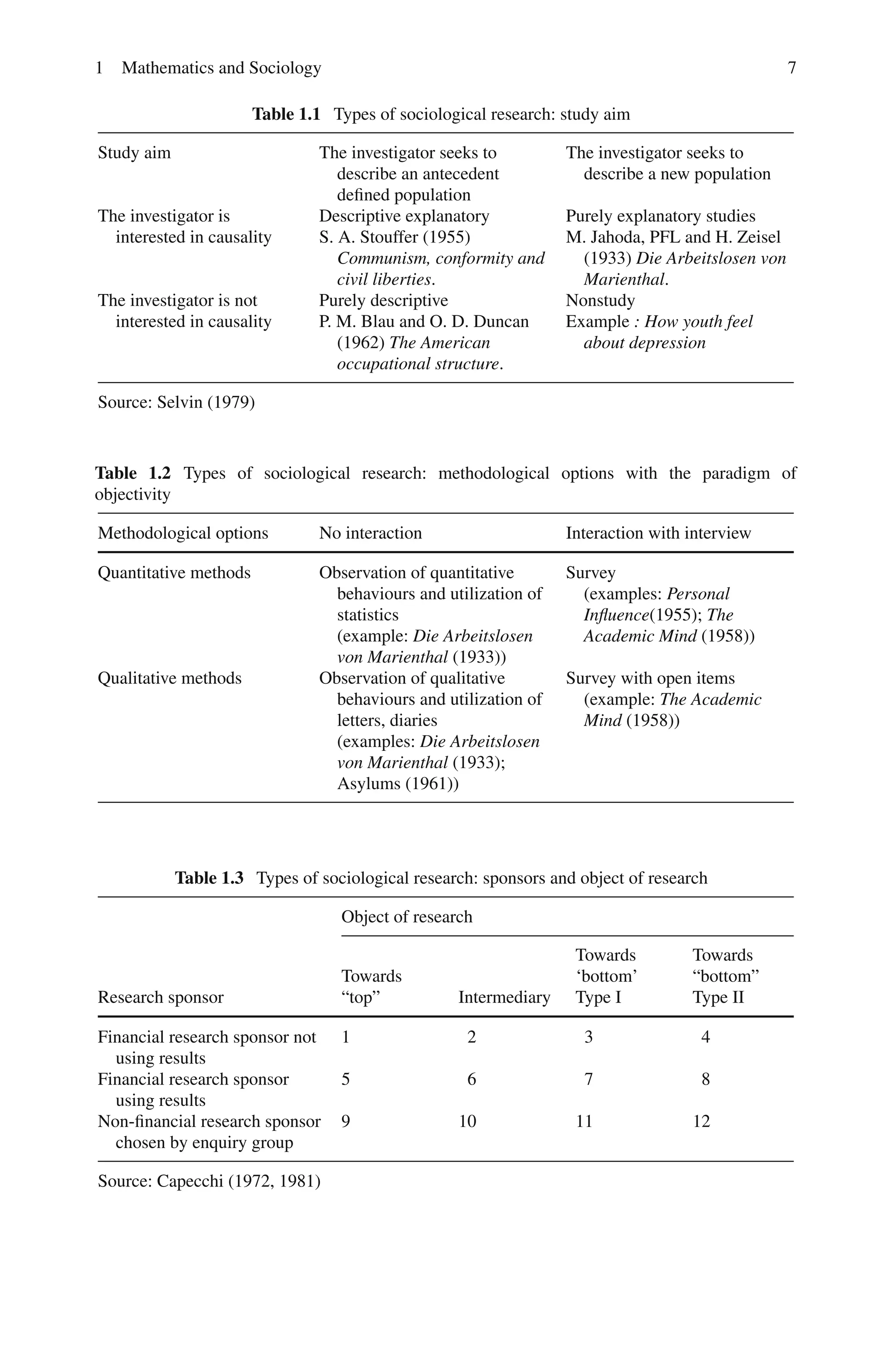

![10 V. Capecchi

circular interpretative model, in which unemployment represented its beginning

and its end: unemployment activates a “process of degradation” which aggravates,

within a negative spiral, the problems about finding a job. Families were classi-

fied into four groups: resigned (48%), apathetic (25%), actives (16%) and desperate

(11%). According to this scheme by Isambert, there are therefore various levels of

degradation families can find themselves in (ranging from resignation to despera-

tion). However, there is also a “deviant minority”: families defined as actives that

try to find new solutions.

This research was highly valued in the Unites States by politically engaged

sociologists such a Robert and Helen Lynd. The Lynds had already published

Middletown (1929) and were influenced by PFL when later on they wrote

Middletown in Transition (1937).

1.1.3 Personal Influence (1955)

1955 was the year of Martin Luther King. In that year in Montgomery, Alabama,

Rosa Parks, a middle-aged lady, decided to rebel against black segregation, which

obliged black people to sit in the back of buses, even when seats in the front were

free. Rosa Parks sat in the front seats of a bus in Montgomery and for this reason she

had to pay a $10 fine. This event convinced Martin Luther King, who in 1955 has

just received his Ph.D. in theology from Boston University, to become the leader of

a pacifist movement for the rights of blacks. He started to boycott buses and in 1956

a sentence of the US Supreme Court declared segregation on buses unconstitutional.

Personal Influence, published in 1955 by PFL in collaboration with Elihu Katz,

was financed by the research office of the Macfadden publications to understand

how to organize an advertisement campaign (in Table 1.3, it is number 7 research).

In this case, the sponsor used the results of the research for market purposes (while

in Die Arbeitslosen von Marienthal the socialist party intended to use the results

to fight back unemployment). This research is made in the period when Lazarsfeld

was active. He had arrived in the United States in 1933 with a Rockefeller fellow-

ship and as part of a wide intellectual migration7 from territories occupied by the

Nazi [on this particular period, see essays by Christian Fleck (1998), Robert Merton

(1998), Seymour Lipset (1998)]. The aim of Personal Influence was to analyse the

influence of mass media on women consumers. PFL wanted to verify the theory

of “two steps flow of communication”, according to which the majority of women

are not directly influenced by mass media but by a net of opinion leaders that are

part of their relations. The method for such verification consisted of three surveys

done between the autumn of 1944 and the spring of 1945, just before the end of

the Second World War. The study focused on some consumer choices (food, house-

hold products, movies and fashion) and the opinions on social and political issues

7See the article by PFL (1969).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/835832-250530051523-48b1bf02/75/Applications-Of-Mathematics-In-Models-Artificial-Neural-Networks-And-Arts-Mathematics-And-Society-1st-Edition-Vittorio-Capecchi-Auth-31-2048.jpg)

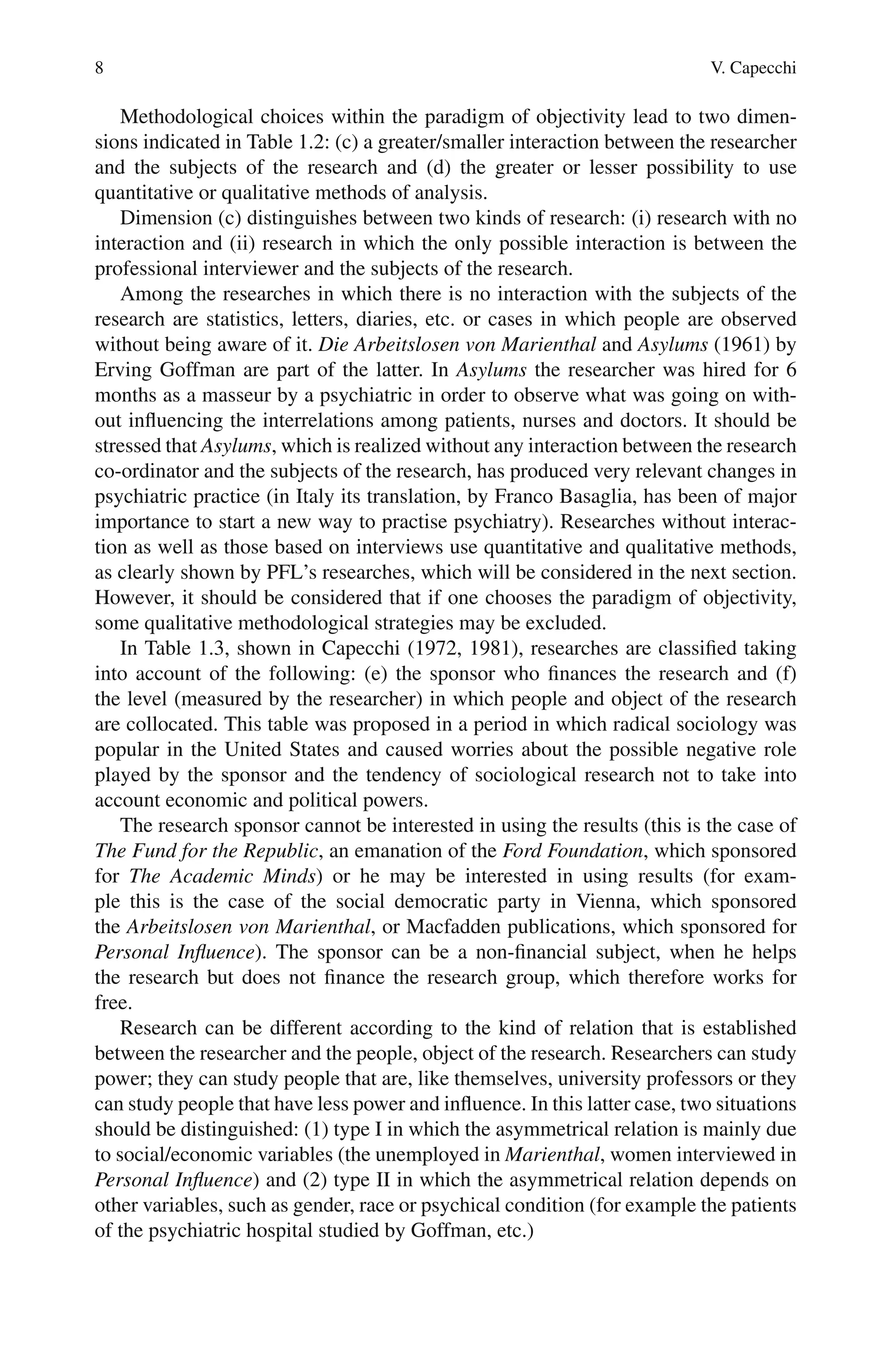

![1 Mathematics and Sociology 15

Social Simulation. Furthermore, changes have occurred in mathematical structure of

models also (due to increased possibilities offered by computer science) and in the

research objectives (the passage from the paradigm of objectivity to the paradigm of

action research/co-research and the paradigm of feminist methodology). The rela-

tion between mathematics and sociology(S → M → S) and (M → S → M) should

therefore be evaluated taking into account what occurs before the actual research

begins, that is to say researchers’ stance and in particular their set of values as well

as methodological and political choices.

The shift from Lazarsfeld’s models to simulation models and to artificial neu-

ral networks has been described in various studies. These have focused not only

on the results of these researches but also on the researchers that made such shift

possible, portraying the complex relationships between university research centres

and laboratories both in Europe and in the United States. The studies by Jeremy

Bernstein (1978, 1982), Pamela McCorduck (1979), Andrei Hodges (1983), James

Gleick (1987), Steve J. Heims (1991), Morris Mitchell Waldrop (1992), Albert-

Laszlo Barabasi (2002) and Linton C. Freeman (2004) are very significant in that

they reconstruct the synergies and contradictions that have led to such changes.

1.2.1 The Paradigm of Action Research/Co-research

The paradigm of action research/co-research differs not only from the one of

objectivity, which, as we have seen, characterizes PFL’s researches, but also from

qualitative researches such as those that have a participant observer and that are

in turn criticized by PFL. Researches that use this paradigm is aimed not only at

finding out explanations but also at changing attitudes and behaviours concerning

people or a specific situation. Kurt Lewin (1946 republished in 1948, pp. 143–149),

who is the first to utilize the term “action research”, gives this definition:

action research [is] a comparative research on the conditions and effects of various form

of social action and research leading to social action. Research that produces nothing but

books will not suffice. This by no means implies that the research needed is in any respect

less scientific or “lower” than what would be required for pure science in the field of social

events (. . .) [action research use] a spiral of steps, each of which is composed of a circle

of planning, action, and fact finding about result of action (. . .) Planning starts usually with

something like a general idea. For one reason or another it seems desirable to reach a certain

objective. Exactly how to circumscribe this objective, and how to reach it, is frequently not

clear. The first step then is to examine the idea carefully on the light of the means available.

(. . .) The next period is devoted to executing the first step of the overall plan. (. . .) The next

step again is composed of a circle of planning, executing, and reconnaissance or fact finding

for the purpose of evaluating the results of the second step, for preparing the rational basis

for planning the third step, and for perhaps modifying again the overall plan.

The action research is different from PFL’s researches in which actions hap-

pen after the publication of the research results; it is also different from researches

that use participant observation. The “intimate familiarity” with the subjects of the

research William Foote Whyte talked about had as its objective knowledge, and in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/835832-250530051523-48b1bf02/75/Applications-Of-Mathematics-In-Models-Artificial-Neural-Networks-And-Arts-Mathematics-And-Society-1st-Edition-Vittorio-Capecchi-Auth-36-2048.jpg)

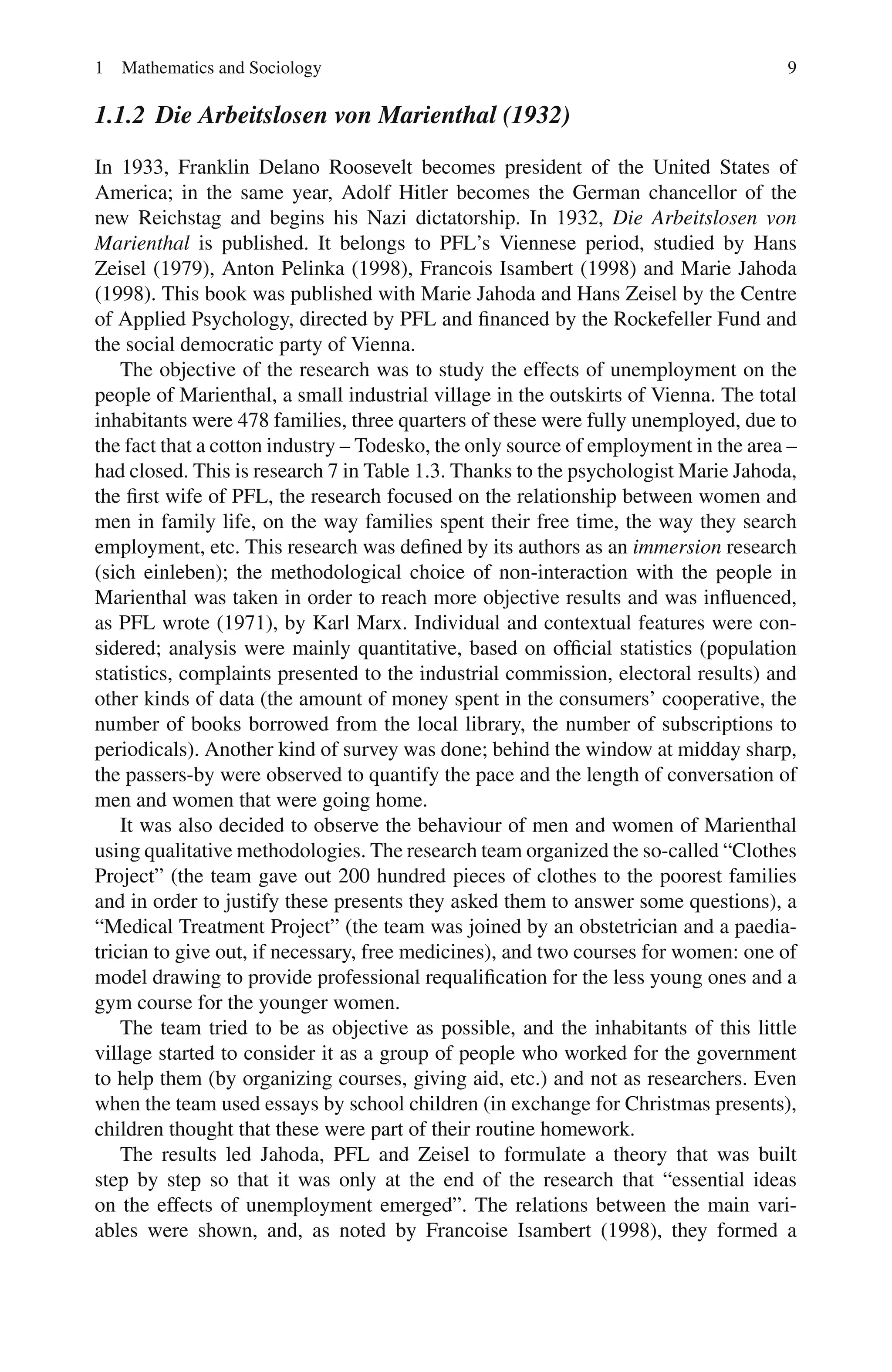

![16 V. Capecchi

a similar fashion, Alfred Mc Clung Lee (1970, p. 7), the author of the introduction

to the Reader entitled The Participant Observer, noted that:

Participant observation is only a gate to the intricacies of more adequate social knowledge.

What happens when one enters that gate depends upon his abilities and interrelationships

as an observer. He must be able to see, to listen, and to feel sensitivity to social interactions

of which he becomes a part.

The objective of the action research/co-research is not only knowledge but

also action, and it is precisely the intertwining between research and action that

characterizes this kind of research.

PFL’s researches and those based on participating observation are characterized

by a [hypothesis→ fieldwork→ analysis→ conclusion] sequence, and differences

are in the type of field work used. In the action research/co-research the sequence is

more complex, as it is characterized by several research steps and actions: [Research

(hypothesis→ fieldwork→ analysis)→ Action (action→ outcomes→ analysis)

→ New research (hypothesis→ fieldwork→ analysis)→ New action (action→

outcomes→ analysis) →]. This different type of research has a spiral process, which

gets interrupted only when the actors of the research have achieved the changes

desired. As Kurt Lewin has noted, “[action research use] a spiral of steps, each of

which is composed of a circle of planning, action, and fact finding about result of

action”.

This type of research functions only if close collaboration between the different

types of actors in the process of research and action takes place. The relationship

between those who coordinate the research and the subjects of the research is there-

fore very different from those researches that follow the paradigm of objectivity, in

which actors and subjects are kept apart. Action research is also very different from

the “intimate familiarity” which is based on participating observation.

In action research/co-research, research is characterized by an explicit agreement

among three different types of actors: (1) those who coordinate the research and the

research team; (2) public or private actors, who take part in the process of changing

and (3) the subjects of the research. Collaboration among these three types of actors

who attempt to bring about changes of attitude and people’s behaviour or a certain

situation allows to (i) reach the necessary knowledge to formulate new theories and

(ii) individuate the necessary action to produce change.

The refusal of the paradigm of objectivity does not mean that in this kind of

research, objectivity is completely absent. Objectivity is in fact pursued through

an ongoing reflection concerning the various steps of the research and all actors’

behaviours and attitudes involved (including those of the co-ordinator). This is

therefore a self-reflective research. Kurt Lewin analyses an example of research

action based in Connecticut in which actors attempt to tackle racist behaviours. He

describes the work of the observers that every day transcribe what happens in the

different steps of the research in order to reach self-reflection:

The method of recording the essential events of who had attended the workshop included an

evaluation session at the end of every day. Observers who had attended the various subgroup

sessions reported (into a recording machine) the leadership pattern they have observed, the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/835832-250530051523-48b1bf02/75/Applications-Of-Mathematics-In-Models-Artificial-Neural-Networks-And-Arts-Mathematics-And-Society-1st-Edition-Vittorio-Capecchi-Auth-37-2048.jpg)

![18 V. Capecchi

Action research/co-research has been very successful, even though its political

use has been overall a downside. For example an international neo-liberalist institu-

tion, such as the World Bank, has used this type of research to try to convince the

native population to take part into multinational programmes, which were aimed at

exploiting them, as documented in Bill Coke and Uma Kothari (2001).

The action research/co-research has followed a trajectory similar to Bruno

Latour’s theories (2005, pp. 8–9). After studying innovations in the scientific field,

he considers two approaches to sociology:

First approach: They believed the social to be made essentially of social ties, whereas asso-

ciation are made of ties which are themselves non-social. They imagined that sociology

is limited to a specific domain, whereas sociologists should travel wherever new hetero-

geneous associations are made. (. . .). I call the first approach “sociology of social” (. . .).

Second approach: Whereas, in the first approach, every activity – law, science, technology,

religion, organization, politics, management, etc. – could be related to and explained by the

same social aggregates behind all of them, in the second version of sociology there exists

nothing behind those activities even though they produce one. (. . .) To be social is no longer

a safe and unproblematic property, it is a movement that may fail to trace any new connec-

tion and may fail to redesign any well-formed assemblage. (. . .) I call the second [approach]

‘sociology of association’.

It is obvious that Latour’s attention to the formation of new collective actors, such

associations (which Latour calls actors-network) finds a parallel in action research,

and distinguishes his approach from those using the paradigm of objectivity. Latour

writes (2005, pp. 124–125):

The question is not whether to place objective texts in opposition to subjective ones. There

are texts that pretend to be objective because they claim to imitate what they believe to be

the secret of the natural sciences; and there are those that try to be objectives because they

track objects which are given the chance to object to what is said about them.

According to Latour, therefore, it is essential that the “objects” of the research

also become “subjects” and have “the chance to object to what is said about them”.

1.2.2 The Paradigm of Feminist Methodology

The paradigm of feminist methodology is closely related to the actions and the-

ories of the world feminist movement. It is precisely this connection that makes

this paradigm very different from the paradigm of objectivity and that of the action

research/co-research. The feminist movement is a heterogeneous collective and

political subject which, in different times and places, has realized different actions

and proposed different theories. Despite such diversity, Caroline Ramazanoglu

and Janet Holland (2002, pp. 138–139) write that when a researcher uses femi-

nist methodology to realize researches for other women, we call this a “feminist

epistemic community”:

An epistemic community is a notion of a socially produced collectivity, with shared rules,

that authorizes the right to speak as a particular kind of knowing subject.(. . .) Feminist

exist as an imagined epistemic community in the sense that they do not need to meet](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/835832-250530051523-48b1bf02/75/Applications-Of-Mathematics-In-Models-Artificial-Neural-Networks-And-Arts-Mathematics-And-Society-1st-Edition-Vittorio-Capecchi-Auth-39-2048.jpg)

![1 Mathematics and Sociology 23

the sociological research and (3) relations in which the relation (M→S→M) is the

strongest.

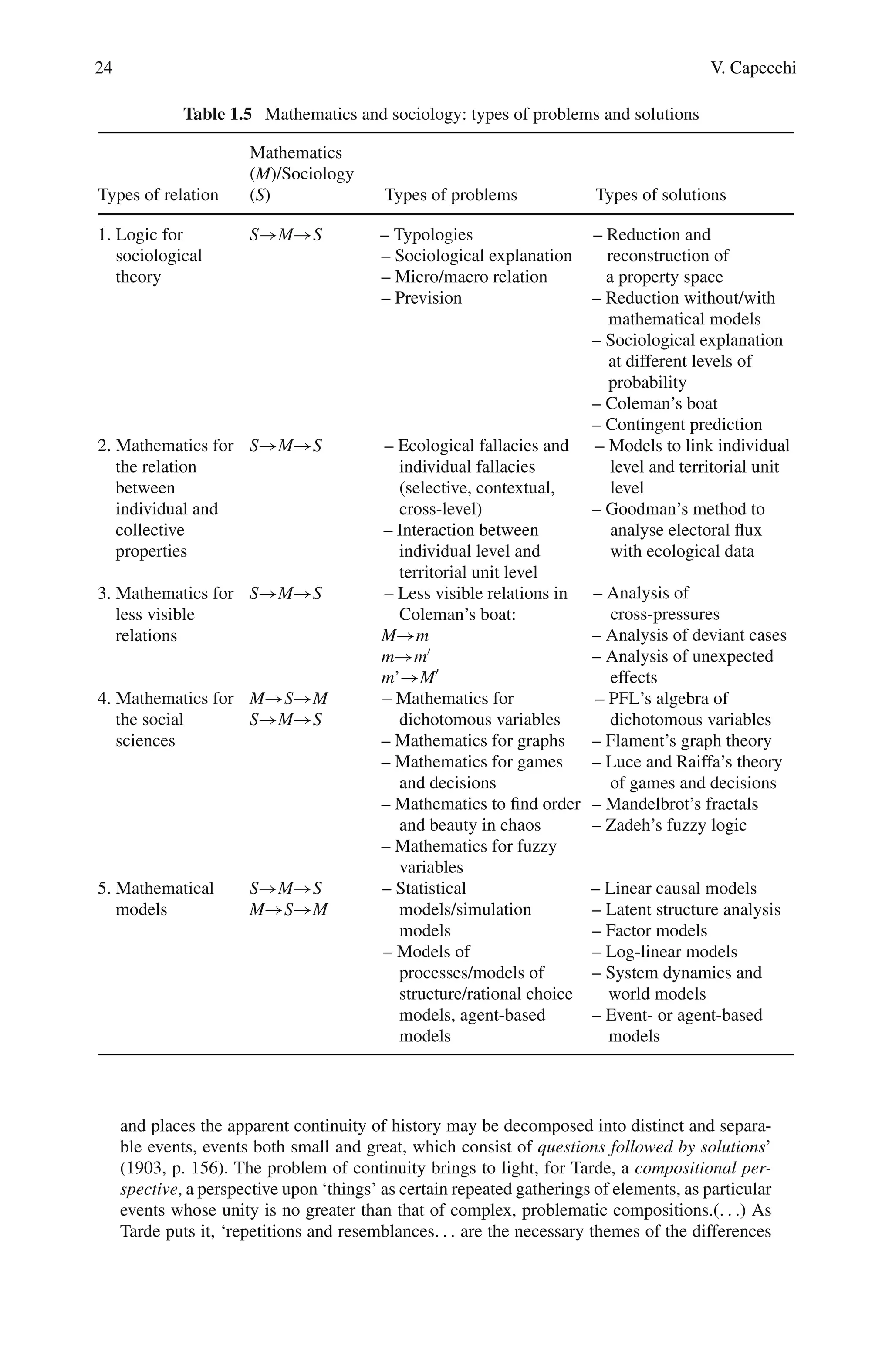

Taking into consideration this more general relation between mathematics and

sociology, it is possible to identify five directions which show interrelation between

mathematics and sociology: (1) logic for sociological theory; (2) mathematics for

relation between individual and collective properties; (3) mathematics and less

visible relations; (4) mathematics for the social sciences and (5) mathematical

models.

These five research directions can be defined through examples that distinguish

between problems and solutions; moreover, Table 1.5 gives an idea of the richness

and complexity that characterize the dialogue between mathematics and sociology.

1.2.3.1 Logic for Sociological Theory

This relation is analysed through four concepts essential for the construction of a

sociological theory: (1) typologies; (2) sociological explanation; (3) micro–macro

relation and (d) prediction.

Typologies

Two debates are interesting as a way of formalizing the concept of typology in

sociological research: (1) the debate between Tarde and Durkheim at the beginning

of the twentieth century concerning the degree of fixity of possible typologies and

(2) the debate between PFL and Carl G. Hempel at the beginning of the 1960s

concerning the plausibility of natural sciences as a reference point for evaluating

typologies proposed by sociology.

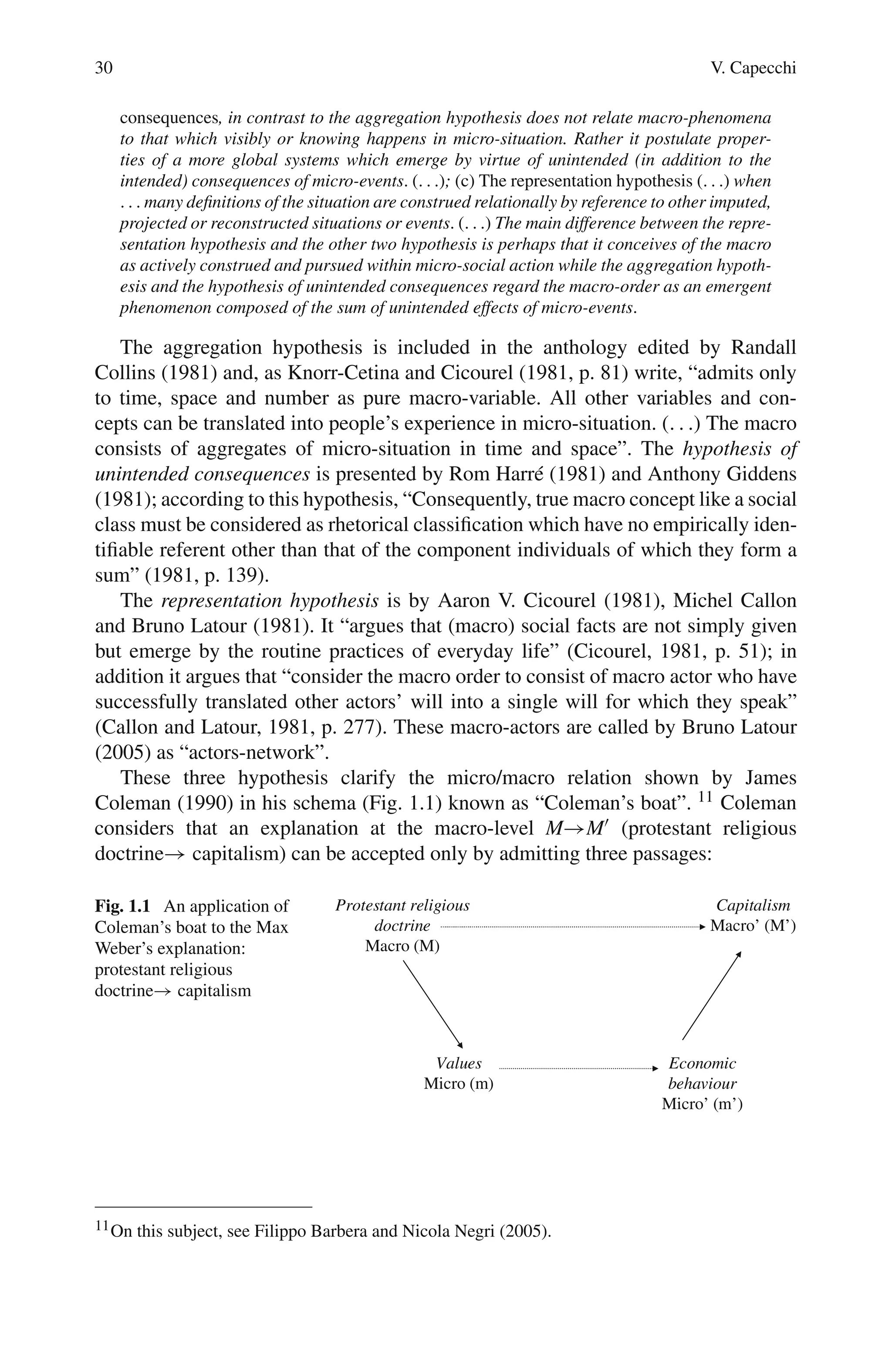

The Gabriel Tarde (1834–1904)–Emile Durkheim (1858–1917) debate ended

with the prevailing of Durkheim’s theories, to the point that Tarde has since then

been ignored in sociological debate, and has been used again only in recent times,

as the works of Gilles Deleuze (1968), Jussi Kinnunen (1996), Bruno Latour (2001)

and David Toews (2003) show. Latour entitles his essay Gabriel Tarde and the End

of the Social because Durkheim is concerned with what he calls “social sociology”

and Tarde is concerned with “sociology of associations”.

Tarde’s attention to the sociology of associations has caused to be considered

as “the founding father of innovation diffusion research”, as Kinnunen has noted

(1996). It is precisely this attention to phenomena that moves and comes together

that has led Tarde to disagree with Durkheim, who, as Deleuze has also noted

(1968), tends on the other hand to construct too rigid and immobile types (such as,

for example, typologies for suicide shown in Table 1.9). As Toews has succinctly

put it:

Durkheim (. . .) explicitly attribute to [social types] a relative solidity (. . .) For Tarde instead

of firm ‘solid’ types of societies, we actually think of reproduction of societies, which

exhibit similar composition. Societies are not made up of an invisible, evolving, quasi-

physical substance, a substance that is indifferent, but in the words of Tarde ‘at all times](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/835832-250530051523-48b1bf02/75/Applications-Of-Mathematics-In-Models-Artificial-Neural-Networks-And-Arts-Mathematics-And-Society-1st-Edition-Vittorio-Capecchi-Auth-44-2048.jpg)

![26 V. Capecchi

justified) and (2) the reconstruction of property space from a given typology in order

to verify if the operation of reduction is correctly carried out.

Two examples of reconstruction of property space are useful to understand why

this method is valid. The first one is the reconstruction of deviant types proposed

by Robert K. Merton (1938, 1949). Merton (Table 1.6) considers the possibilities

that an individual has to accept goals or institutional means offered by society to

individuals.

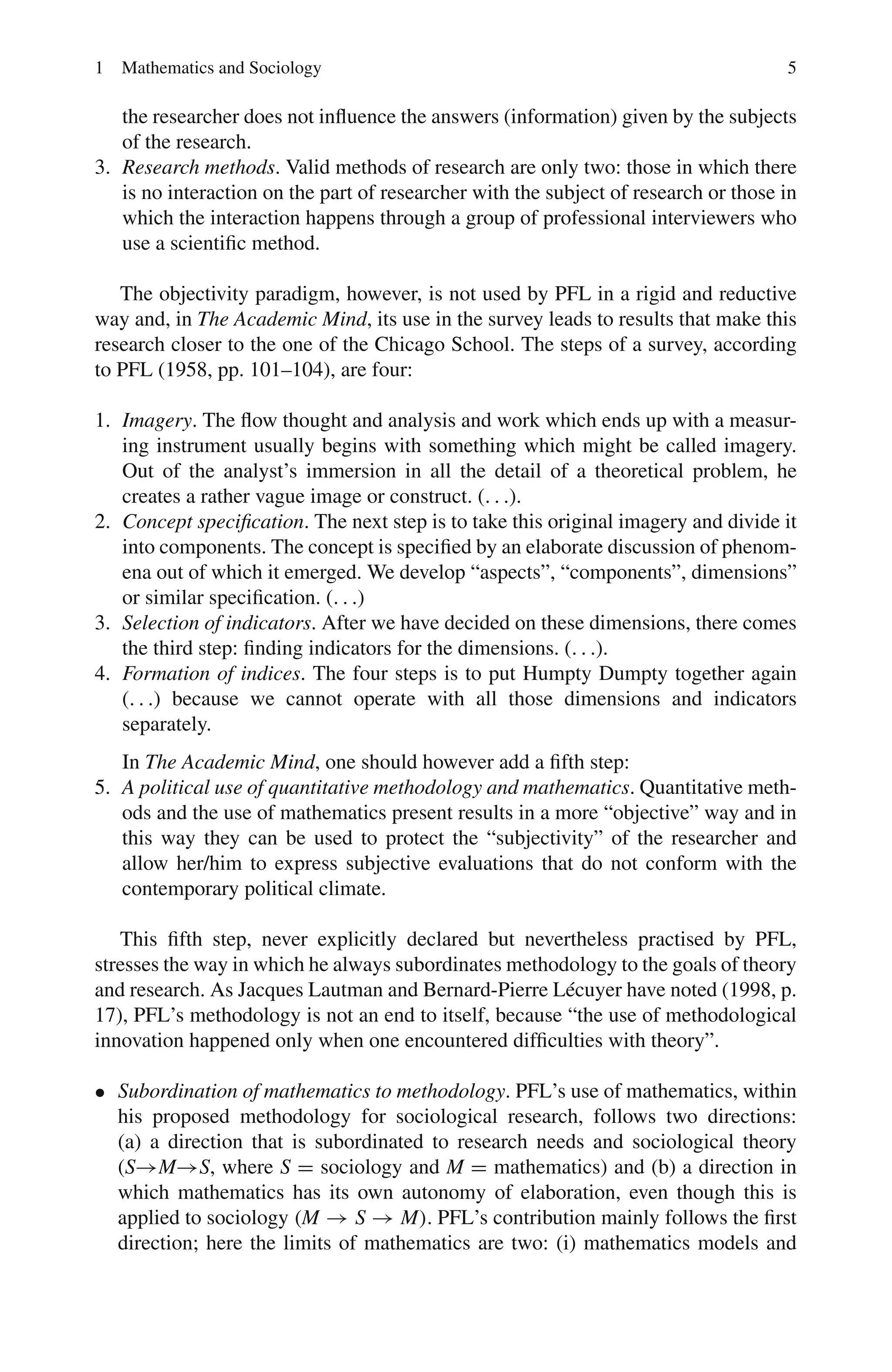

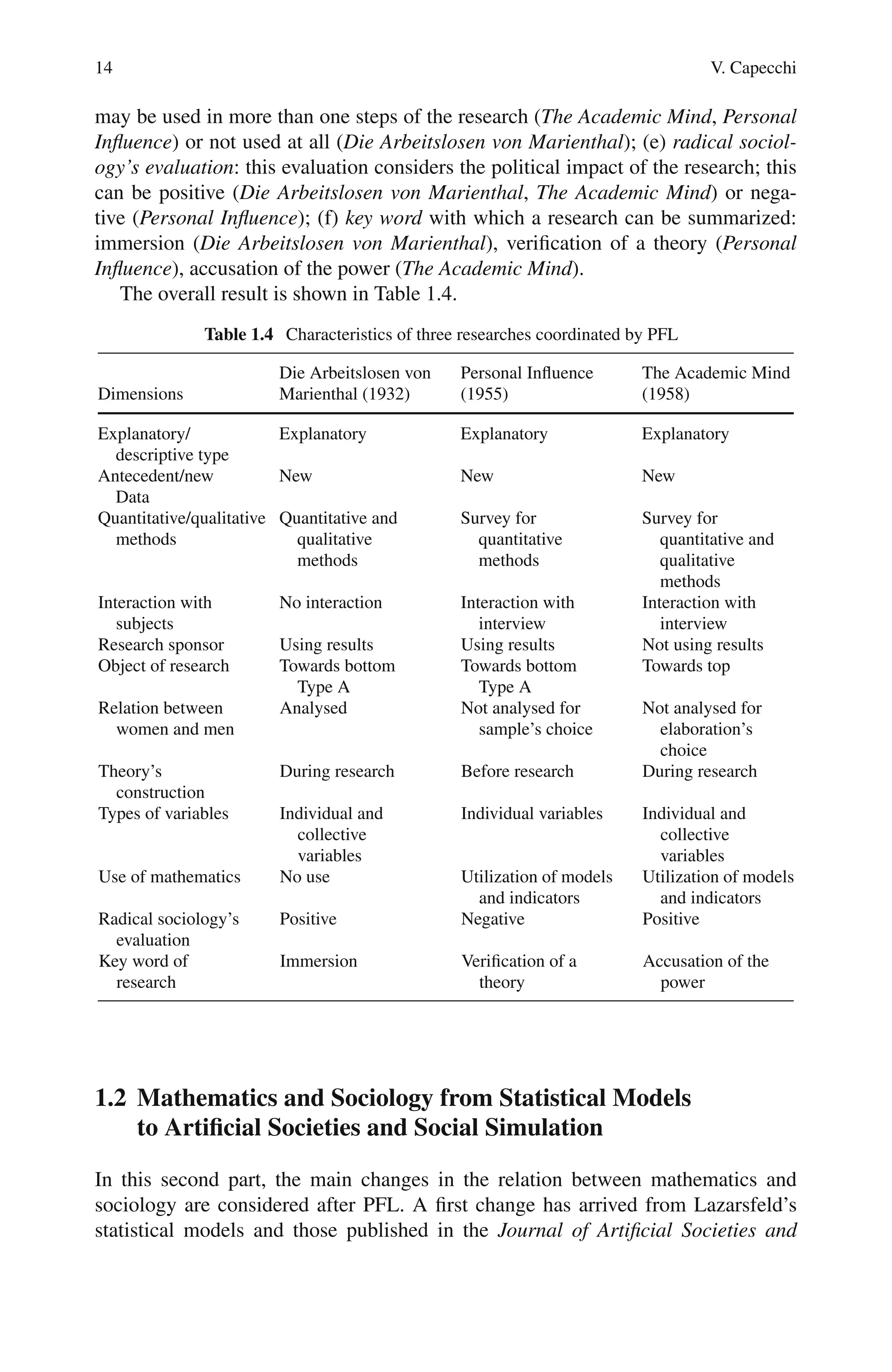

Table 1.6 Merton’s typology of deviant behaviour

Types of adaptation

Modes of adaptation to

culture goals

Modes of adaptation to

institutional means

I. Conformity + +

II. Innovation + −

III. Ritualism − +

IV. Retreatism − −

V. Rebellion ± ±

Source: Merton (1938, 1949)

The sign (+) indicates “acceptance”, the sign (−) indicates “rejection” and the sign (±) indicates

“substitution”

This theory was well received because it was related to some unusual analysis.

For example under Type II “Innovation”, it included the condition of Italo-American

gangsters in New York. These fully accepted (+) the goals proposed by American

society, but as Italians they encountered obstacles, and for this reason they rejected

(−) the institutional means to reach such goals.

During the 1960s, while working for the Bureau of Applied Social Research and

editing the Italian edition of PFL’s collected work, I amused myself by trying to

apply what I had learnt from PFL in order to challenge the typology proposed by

his friend Robert King Merton. The result10 was published in Capecchi (1963, 1966)

and is summarized in Table 1.7. This adds to new elements to Table 1.6: (a) Type

II Innovation was wrongly placed, because, according to Merton, this is a type that

accepts (+) goals; however, he refuses legal means in order to merely substitute (±)

them and (b) four new types [3], [4], [6], [8] also emerge, and they are plausible and

interesting.

Another example is the reconstruction of the well-known typology of suicides

by Durkheim (Table 1.8), which Hempel would have later defined as extreme types,

who collocates four types of suicides in a table that analyses two separate dimen-

sions (solidarity and laws). Of these two dimensions, the destructive effects of

people who are in extreme situations (lack of/too much solidarity; lack of/too much

laws) are considered. Table 1.8 is interesting because it suggests a more modern

image of types of suicides, which according to Tarde were too rigid. Maintaining

10Capecchi’s reconstruction of Merton’s typology of deviance was appreciated by Blalock (1968,

p. 30–31) and an analysis of this reconstruction of deviance from a sociological point of view is in

Berzano and Prina (1995, p. 85).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/835832-250530051523-48b1bf02/75/Applications-Of-Mathematics-In-Models-Artificial-Neural-Networks-And-Arts-Mathematics-And-Society-1st-Edition-Vittorio-Capecchi-Auth-47-2048.jpg)

![1 Mathematics and Sociology 27

Table 1.7 Reconstruction of Merton’s types of adaptation

Adaptation to culture goals

Adaptation to

institutional means + − ±

+ I. Conformity [1] III. Ritualism [2] Revolution within the

system [3]

− Estrangement [4] IV. Retreatism [5] Inactive opposition [6]

± II. Innovation [7] Exasperation [8] V. Rebellion [9]

Source: Capecchi (1963, 1966)

Table 1.8 Reconstruction of Durkheim’s types of suicide

Dimensions Danger of self-destruction for

lack of

Danger of self-destruction for

too much

Solidarity Lack of solidarity: egoistic

suicide

Too much solidarity: altruistic

suicide

Laws Lack of laws: anomic suicide Too much laws: ritualistic

suicide

Source: Durkheim (1897)

that single members of a society should try to avoid extreme situations means to

share a view that is widespread in religion such as Taoism and Zen Buddhism, as

both positions stress the importance of moving along a “fuzzy” dimension, in a

continuum between two extremes.

It is important to note that Merton and Durkheim’s typologies can be represented

in research/action frameworks (because they are typologies that consider processes

and not static types), but they do not take into account gender differences (and are

therefore easily challenged by feminist methodology). A double attention to chang-

ing processes and feminist perspectives should be considered in the construction

of all typologies. In Table 1.9, the logical operations of reduction of a property

space are together with two different modalities: (1) with or without the results of a

research and (2) with or without mathematical models. The types based on results

of a research are classificatory types, while those not based on results are extreme

Table 1.9 The types of reduction of a property space in a typology

Types of reduction

Without mathematical

models With mathematical models

Without the result of a

research

Pragmatic reduction Reduction through indices

With the result of a

research

Reduction according to

frequencies

Reduction according to

mathematical indices and

models

Source: Capecchi (1966)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/835832-250530051523-48b1bf02/75/Applications-Of-Mathematics-In-Models-Artificial-Neural-Networks-And-Arts-Mathematics-And-Society-1st-Edition-Vittorio-Capecchi-Auth-48-2048.jpg)

![28 V. Capecchi

or ideal types. The types proposed however should be evaluated not only in relation

to a correct formal method of reduction but also in relation to the values that define

their content.

Sociological explanation

A possible clarification of sociological theory can be gathered from the contribution

given by logic to the definition of “sociological explanation”. Hempel (1965, p. 250)

describes the characteristic of a causal law and a statistical law in science:

If E [Explanandum] describe a particular event, then the antecedent circumstances

[Explanans] described in the sentences C1, C2,. . .Ck may be said jointly the “cause” of the

event, in the sense that there are certain empirical regularities, expressed by the laws L1,

L2,. . .Lr which imply whenever conditions of the kind indicated by C1, C2,. . .Ck occur an

event of this kind described in E will take place. Statements such as L1, L2,. . .Lr which

assert general and unexceptional connections between specific characteristics of events, are

customarily called causal, or deterministic laws. They must be distinguished from so called

statistical laws which assert that in the long run, an explicitly stated percentages of all cases

satisfying a given set of conditions are accompanied by an event of a certain specific kind.

As a consequence of this definition, based on sciences, such as physics, soci-

ology has proceeded following two different trajectories: (1) it adopted as point of

reference natural sciences, such as biology, that are closer to sociology than classical

physics. As Stanley Lieberson and Freda B. Lynn have written (2002):

The standard for what passes as scientific sociology is derived from classical physics, a

model of natural science that is totally inappropriate for sociology. As a consequence,

we pursue goals and use criteria for success that are harmful and counterproductive. (. . .)

Although recognizing that no natural science can serve as an automatic template for our

work, we suggest that Darwin’s work on evolution provides a far more applicable model for

linking theory and research since he dealt with obstacles far more similar to our own. This

includes drawing rigorous conclusions based on observational data rather than true experi-

ments; an ability to absorb enormous amounts of diverse data into a relatively simple system

that not include a large number of what we think of as independent variables; the absence

of prediction as a standard for evaluating the adequacy of a theory; and the ability to use a

theory that is incomplete in both the evidence that supports it and in its development.

(2) It looked for a multileveled “sociological explanation” in order to pro-

pose “sociological explanations” that had weaker conditions than those shown by

Hempel’s “causal law”. To explain this second trajectory, one can begin by consid-

ering Raymond Boudon (1995), who considers the macro-sociological explanation

proposed by Max Weber: protestant religious doctrine→ capitalism. Boudon relates

Weber’s theory with facts that have emerged through empirical researches and

obtains three situations: (1) facts that are explained by theories (for example Trevor

Roper’s researches. These show that several entrepreneurs in Calvinist areas, such

as Holland, were not Calvinist but immigrants with other religious values); (ii) the-

ory is not enough to explain facts (for example Scotland is from an economic point

of view a depressed area, even though it is next to England and here Calvinism

is as widespread as in England. In order to explain this situation a different the-

ory is needed); (iii) facts coincide with theories (as is the case with the success](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/835832-250530051523-48b1bf02/75/Applications-Of-Mathematics-In-Models-Artificial-Neural-Networks-And-Arts-Mathematics-And-Society-1st-Edition-Vittorio-Capecchi-Auth-49-2048.jpg)

![This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United

States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away

or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License

included with this ebook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the

laws of the country where you are located before using this

eBook.

Title: Népmesék Heves- és Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok-megyéből;

Magyar népköltési gyüjtemény 9. kötet

Annotator: Lajos Katona

Author: János Berze Nagy

Editor: Gyula Vargha

Release date: August 30, 2013 [eBook #43603]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: Hungarian

Credits: Produced by an anonymous volunteer from page

images

generously made available by the Google Books Library

Project

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NÉPMESÉK

HEVES- ÉS JÁSZ-NAGYKUN-SZOLNOK-MEGYÉBŐL; MAGYAR

NÉPKÖLTÉSI GYÜJTEMÉNY 9. KÖTET ***](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/835832-250530051523-48b1bf02/75/Applications-Of-Mathematics-In-Models-Artificial-Neural-Networks-And-Arts-Mathematics-And-Society-1st-Edition-Vittorio-Capecchi-Auth-60-2048.jpg)