This document summarizes a report on the implementation of the Brussels Programme of Action (BPoA) for Least Developed Countries in Africa. Some key points:

- Economic growth in African LDCs reached over 7% for several years but did not significantly reduce poverty. Growth was driven by commodity exports and not inclusive.

- Some progress was made in areas like education but not in water, sanitation, or health.

- Trade remains concentrated in primary commodities, leaving countries vulnerable to external shocks. Access to markets is still limited.

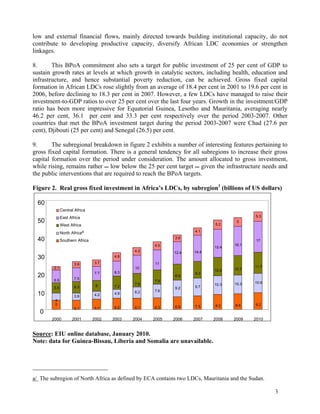

- Official development assistance has not reached pledged amounts and has been directed to non-productive sectors, limiting investment in productive capacities.