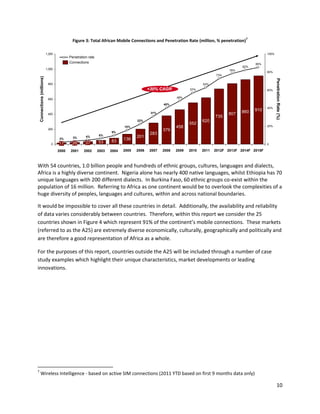

The mobile industry in Africa has experienced rapid growth over the past decade, with the number of connections doubling from 2007-2011. Africa has overtaken Latin America as the second largest mobile market in the world, with over 620 million connections as of 2011. The market is highly competitive, resulting in significant price reductions of up to 60% over 2007-2011. While mobile penetration has increased to over 57%, there remains potential for further growth, as 36% of Africans in the top 25 markets still lack access to mobile services.