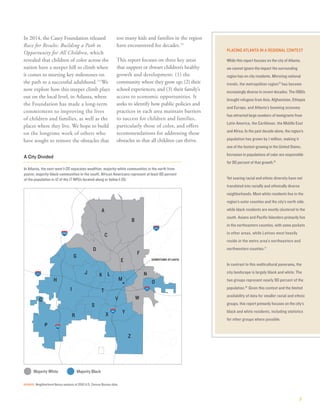

This document summarizes a report examining barriers to opportunity for children in Atlanta. It finds that the city remains highly segregated, with wealthier white communities in the north separated from poorer black communities in the south by Interstate 20. Children in southern neighborhoods face numerous challenges like high poverty rates, limited access to resources, and segregated, low-performing schools. The report examines how factors like Atlanta's history of segregation and urban renewal have contributed to deep inequities between communities that continue to shape children's life outcomes and opportunities along racial lines.