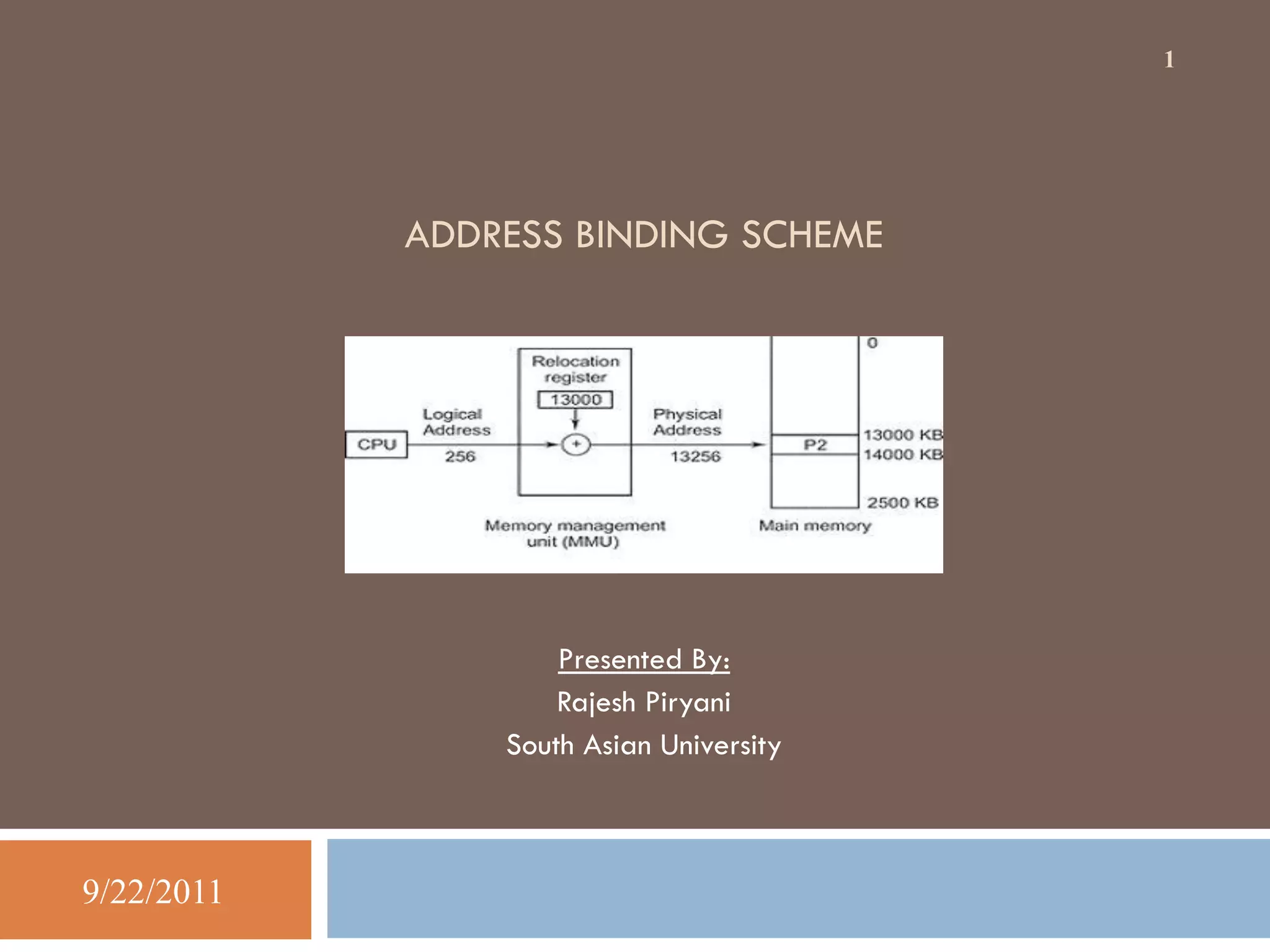

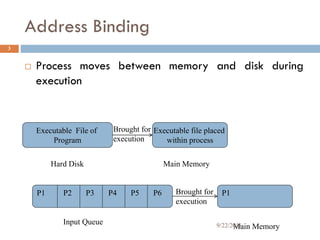

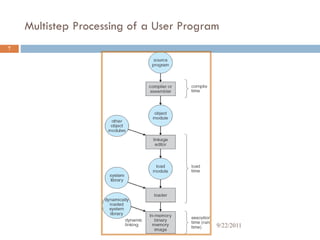

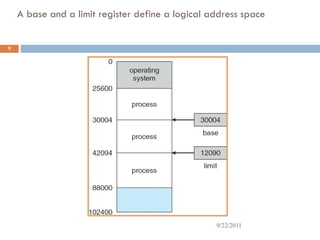

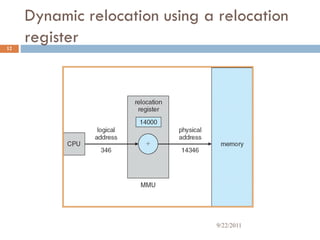

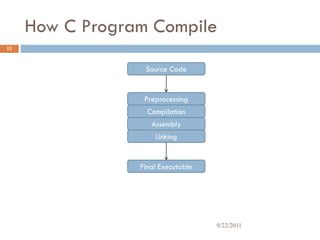

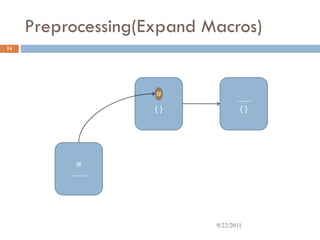

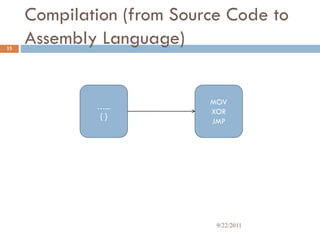

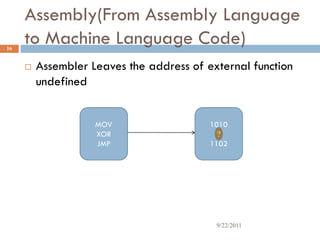

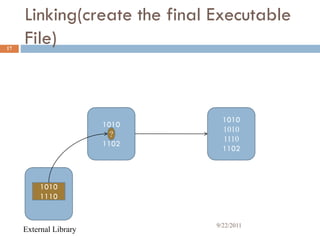

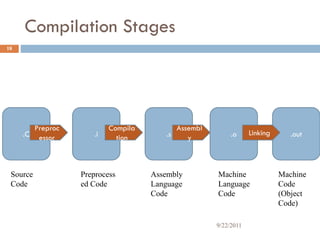

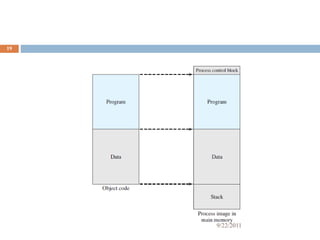

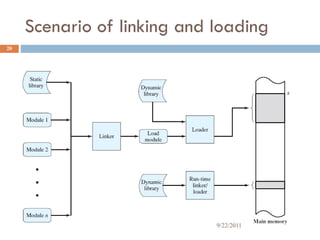

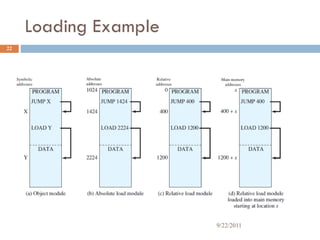

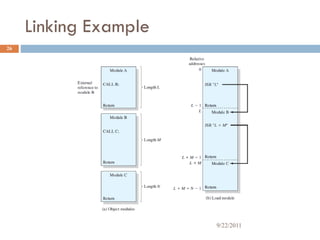

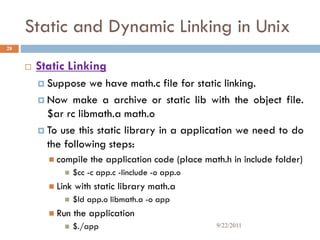

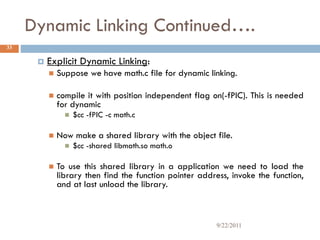

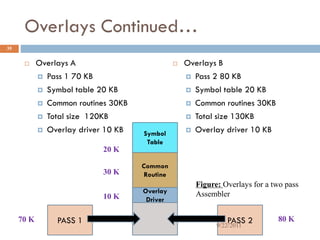

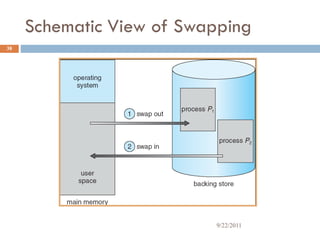

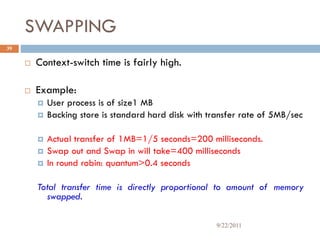

The document discusses address binding schemes in computer systems. It describes the different types of addresses used in the binding process, including symbolic addresses, relocatable addresses, and absolute addresses. It also discusses how processes move between memory and disk during execution and the role of input queues. Linking and loading of programs is explained, along with concepts like overlays and swapping to enable processes to be larger than available memory.