A Functional Approach to Java: Augmenting Object-Oriented Java Code with Functional Principles 1st Edition Ben Weidig

A Functional Approach to Java: Augmenting Object-Oriented Java Code with Functional Principles 1st Edition Ben Weidig

A Functional Approach to Java: Augmenting Object-Oriented Java Code with Functional Principles 1st Edition Ben Weidig

![978-1-098-10992-9

[LSI]

A Functional Approach to Java

by Ben Weidig

Copyright © 2023 Benjamin Weidig. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are

also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional

sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

Acquisitions Editor: Brian Guerin

Development Editor: Rita Fernando

Production Editor: Ashley Stussy

Copyeditor: Liz Wheeler

Proofreader: Piper Editorial Consulting, LLC

Indexer: WordCo Indexing Services, Inc.

Interior Designer: David Futato

Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery

Illustrator: Kate Dullea

May 2023: First Edition

Revision History for the First Edition

2023-05-09: First Release

2024-02-02: Second Release

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781098109929 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. A Functional Approach to Java, the

cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

The views expressed in this work are those of the author, and do not represent the publisher’s views.

While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and

instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility

for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use

of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your

own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open

source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use

thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/101893-250423053718-7e74e856/85/A-Functional-Approach-to-Java-Augmenting-Object-Oriented-Java-Code-with-Functional-Principles-1st-Edition-Ben-Weidig-7-320.jpg)

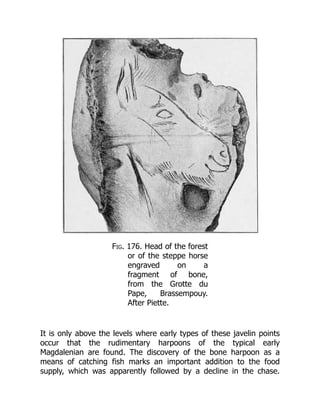

![perforation opposite

the brow tine. After

Lartet and Christy.

"The religious phenomenon," observes James,(3) "has shown itself to

consist everywhere, and in all its stages, in the consciousness which

individuals have of an intercourse between themselves and higher

powers with which they feel themselves to be related. This

intercourse is realized at the time as being both active and mutual....

The gods believed in—whether by crude savages or by men

disciplined intellectually—agree with each other in recognizing

personal calls.... To coerce the spiritual powers, or to square them

and get them on our side, was, during enormous tracts of time, the

one great object in our dealings with the natural world."

The study of this race, in our opinion, would suggest a still earlier

phase in the development of religious thought than that considered

by James, namely, a phase in which the wonders of nature in their

various manifestations begin to arouse in the primitive mind a desire

for an explanation of these phenomena, and in which it is attempted

to seek such cause in some vague supernatural power underlying

these otherwise unaccountable occurrences, a cause to which the

primitive human spirit commences to make its appeal. According to

certain anthropologists,[AU] this wonder-working force may either be

personal, like the gods of Homer, or impersonal, like the Mana of the

Melanesian, or the Manitou of the North American Indian. It may

impress an individual when he is in a proper frame of mind, and

through magic or propitiation may be brought into relation with his

individual ends. Magic and religion jointly belong to the supernatural

as opposed to the every-day world of the savage.

We have already seen evidence from the burials that these people

apparently believed in the preparation of the bodies of the dead for

a future existence. How far these beliefs and the votive sense of

propitiation for protection and success in the chase are indicated by](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/101893-250423053718-7e74e856/85/A-Functional-Approach-to-Java-Augmenting-Object-Oriented-Java-Code-with-Functional-Principles-1st-Edition-Ben-Weidig-52-320.jpg)