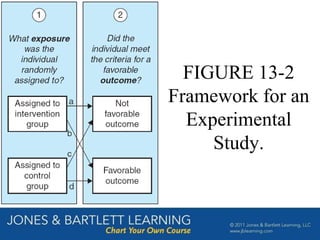

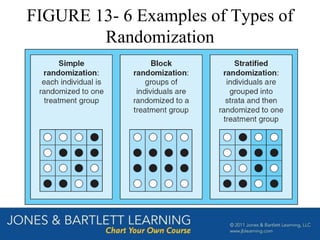

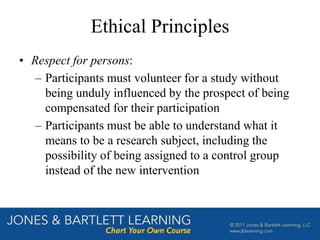

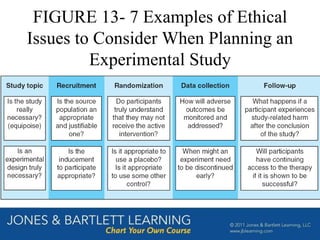

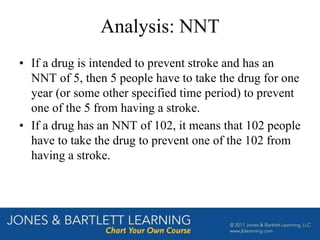

Experimental studies assign participants to intervention and control groups to examine if an intervention causes an intended outcome. Randomized controlled trials randomly assign participants to an active intervention or control group and follow them over time. Researchers must carefully define the intervention, outcomes, controls, and address ethical concerns like ensuring participants understand they may receive the control instead of the intervention. Analyses include measures of association, efficacy, and the number needed to treat to prevent an unfavorable outcome in one person.