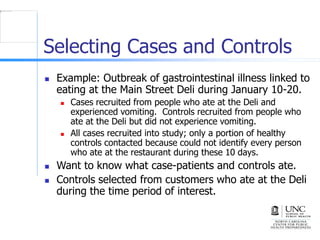

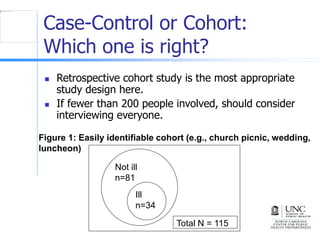

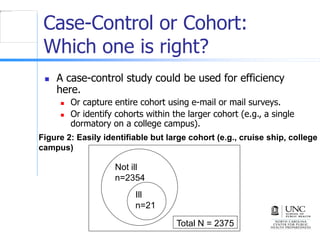

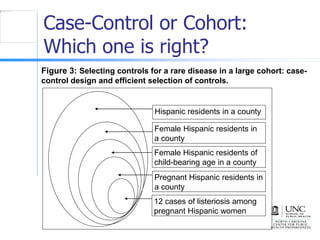

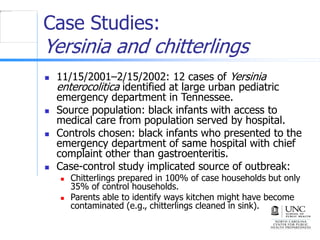

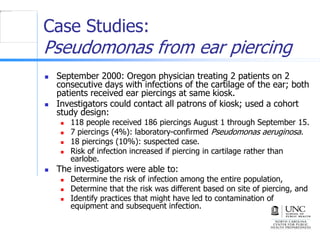

This document describes cohort and case-control study designs. Cohort studies follow groups over time to compare disease occurrence between exposed and unexposed groups. Case-control studies identify people with and without a disease and compare past exposures. Cohort studies are best when the entire population is identifiable, while case-control studies are more efficient when the population is large or undefined. The document provides examples of outbreak investigations that effectively used each design.