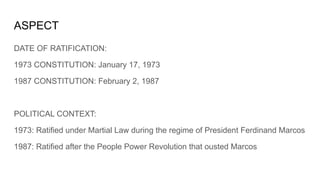

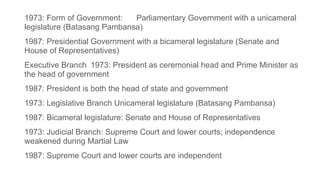

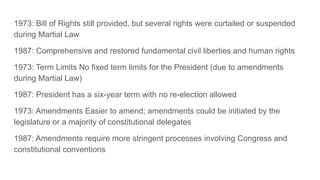

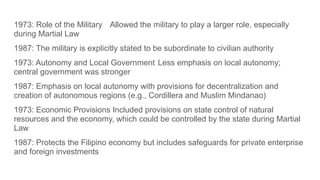

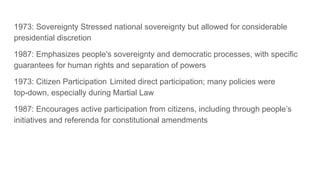

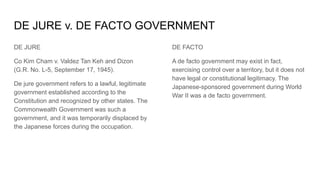

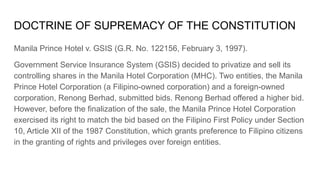

The document compares the 1973 and 1987 constitutions of the Philippines, highlighting key differences in political context, government structure, and civil liberties. It discusses various legal cases illustrating constitutional principles such as the supremacy of the constitution, separation of powers, checks and balances, and the requirements for citizenship and martial law declarations. Ultimately, it emphasizes the evolution of democratic governance and rule of law from the 1973 to the 1987 constitution.

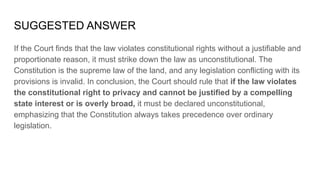

![SUGGESTED ANSWER

The 1987 Constitution clearly vests the power of the purse in Congress. Under

Article VI, Section 29(1), it states that "[n]o money shall be paid out of the

Treasury except in pursuance of an appropriation made by law." This means that

the allocation of public funds must be approved by Congress through the passage

of the General Appropriations Act or a supplemental budget law. Supreme Court

should declare the executive order invalid if it finds that the President acted

outside the bounds of executive authority by reallocating funds without the

approval of Congress. The ruling would reinforce the constitutional principle that

the executive cannot exercise powers reserved for the legislature.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1987constivis-a-vis1973constitution-241013151312-c8c8861d/85/1987-consti-vis-a-vis-1973-Constitution-pdf-14-320.jpg)