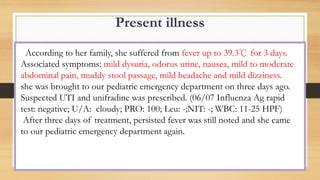

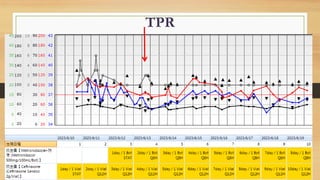

1. The patient presented with persistent fever and abdominal pain and was diagnosed with infectious enterocolitis, likely caused by rotavirus. Imaging showed colitis of the ascending colon with suspected perforation and abscess formation.

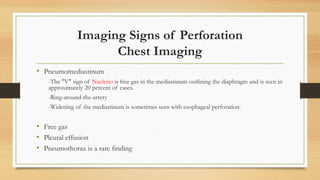

2. Gastrointestinal perforation requires full-thickness injury to the bowel wall and can result from various medical and surgical causes. Clinical features depend on the location and contents released.

3. Management involves IV fluids, antibiotics, and surgery to repair the perforation site for patients with signs of peritonitis or worsening symptoms. Some perforations can be managed non-operatively with antibiotics if the perforation is contained.