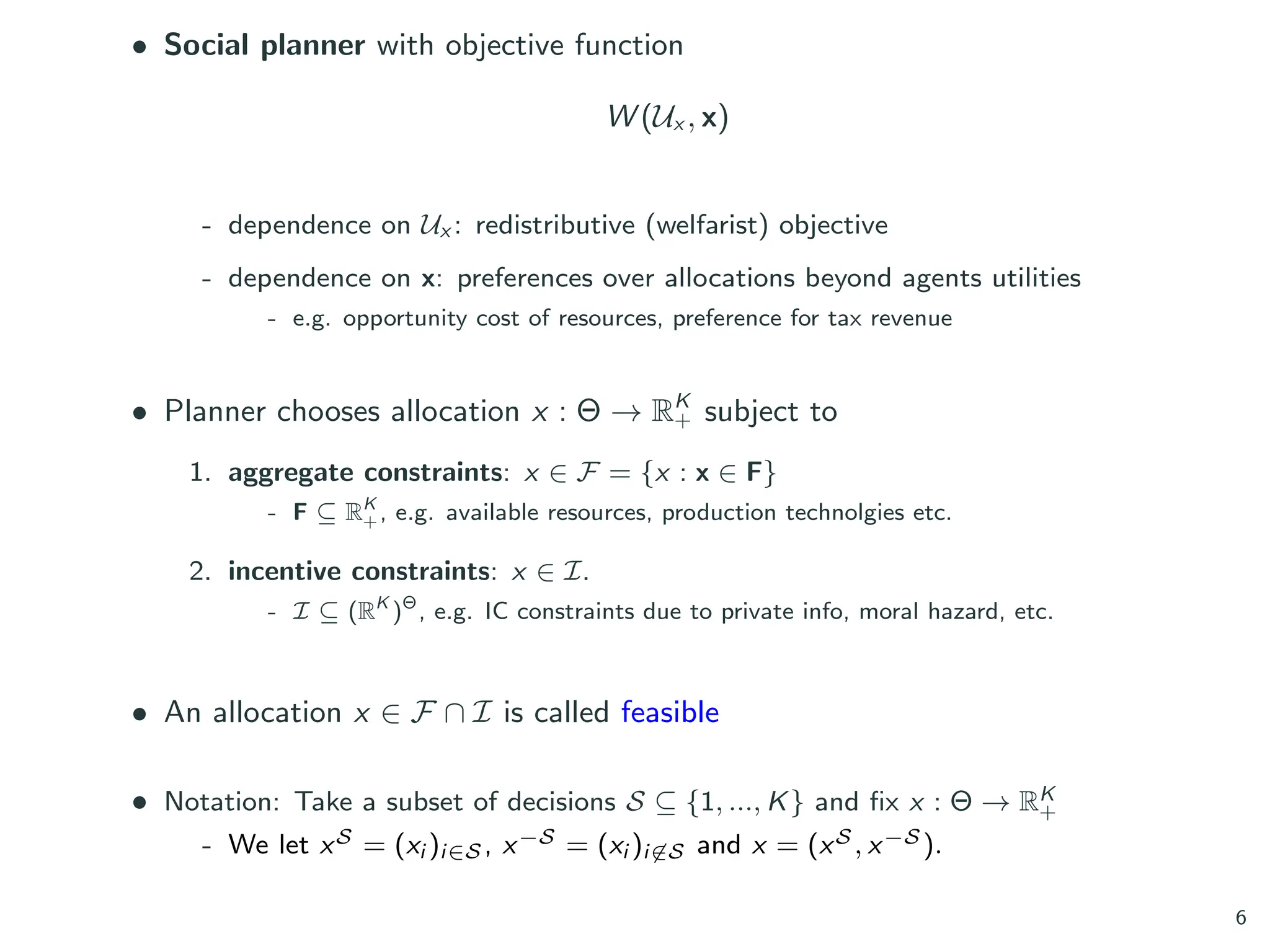

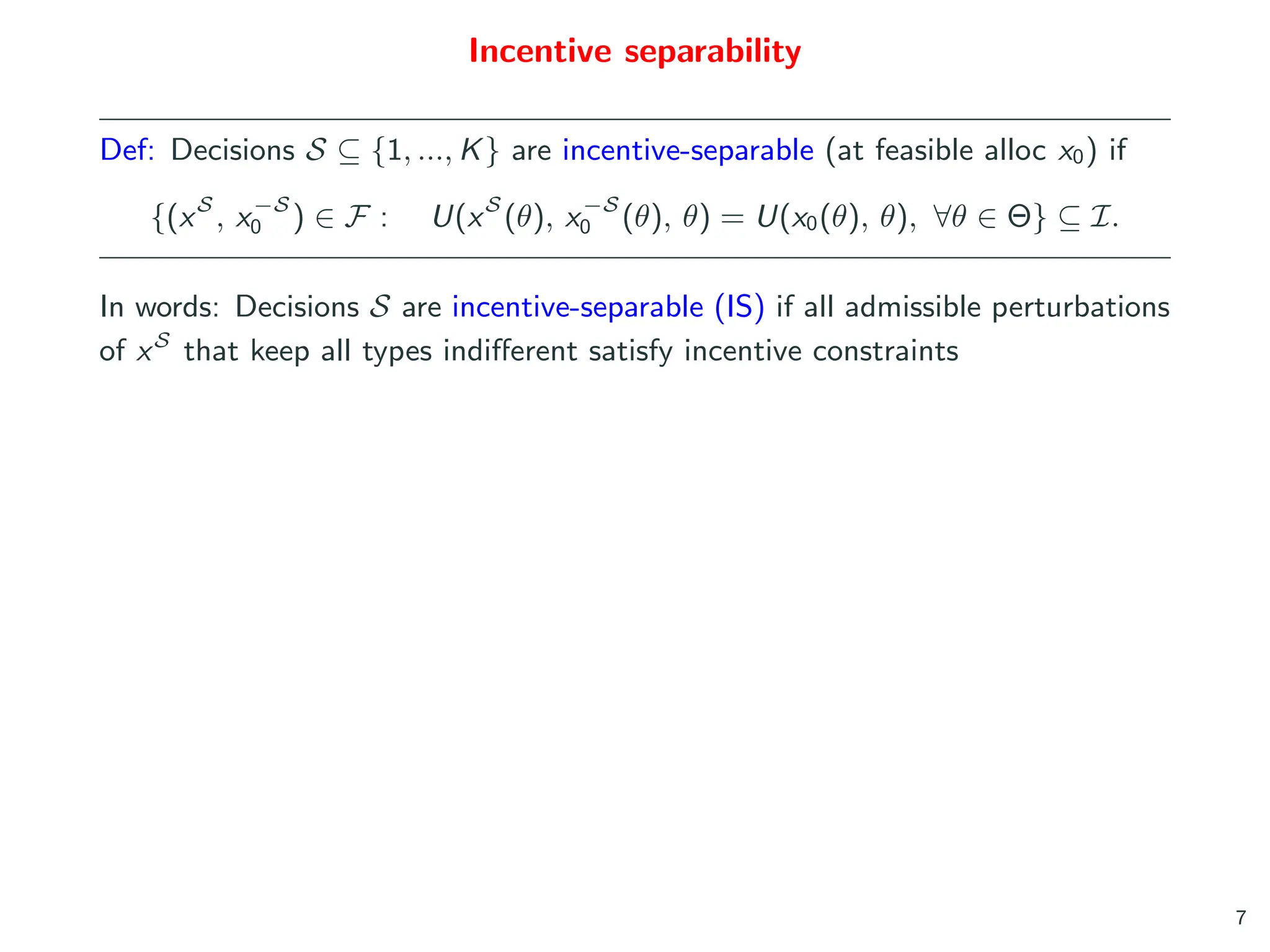

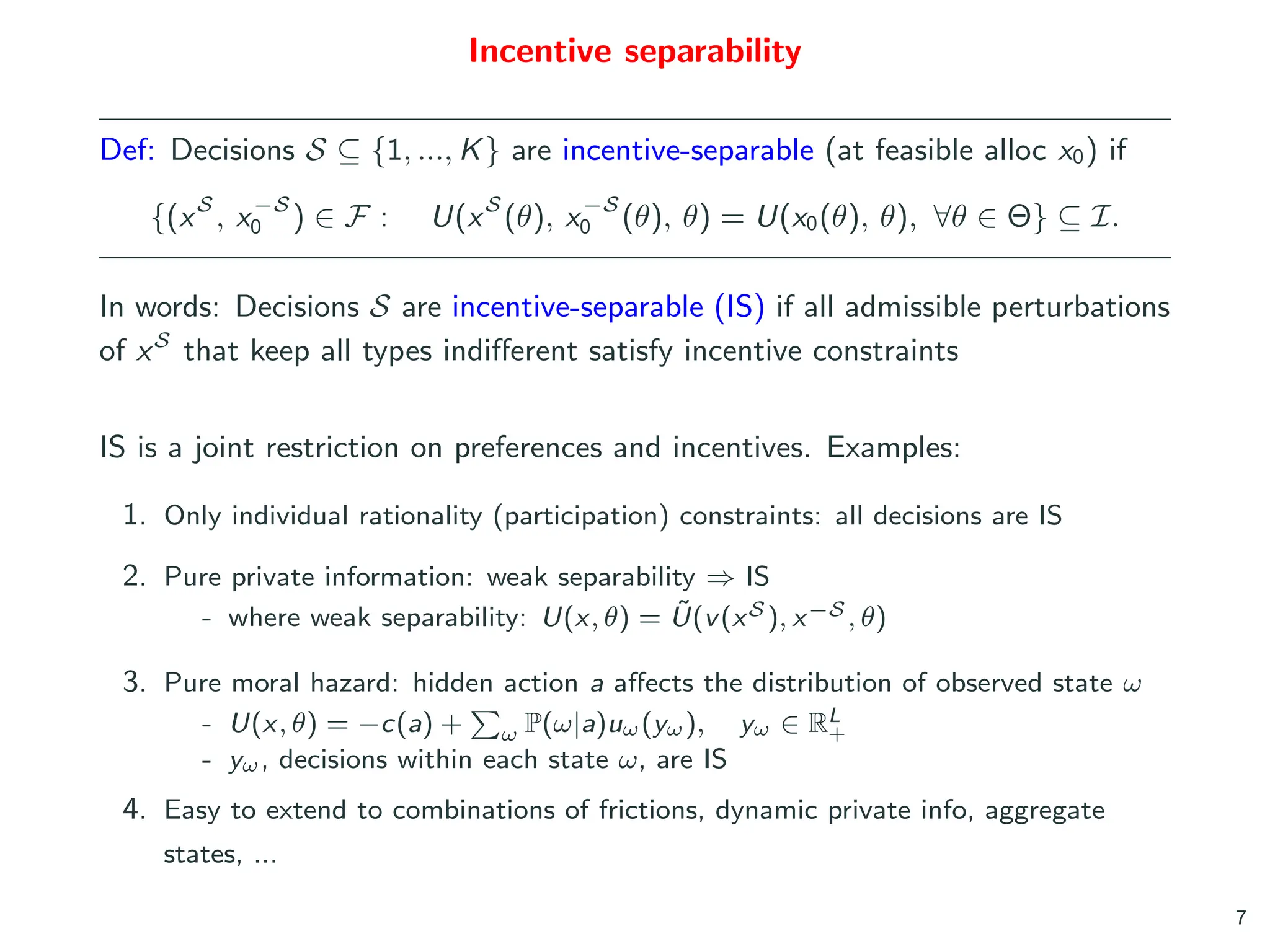

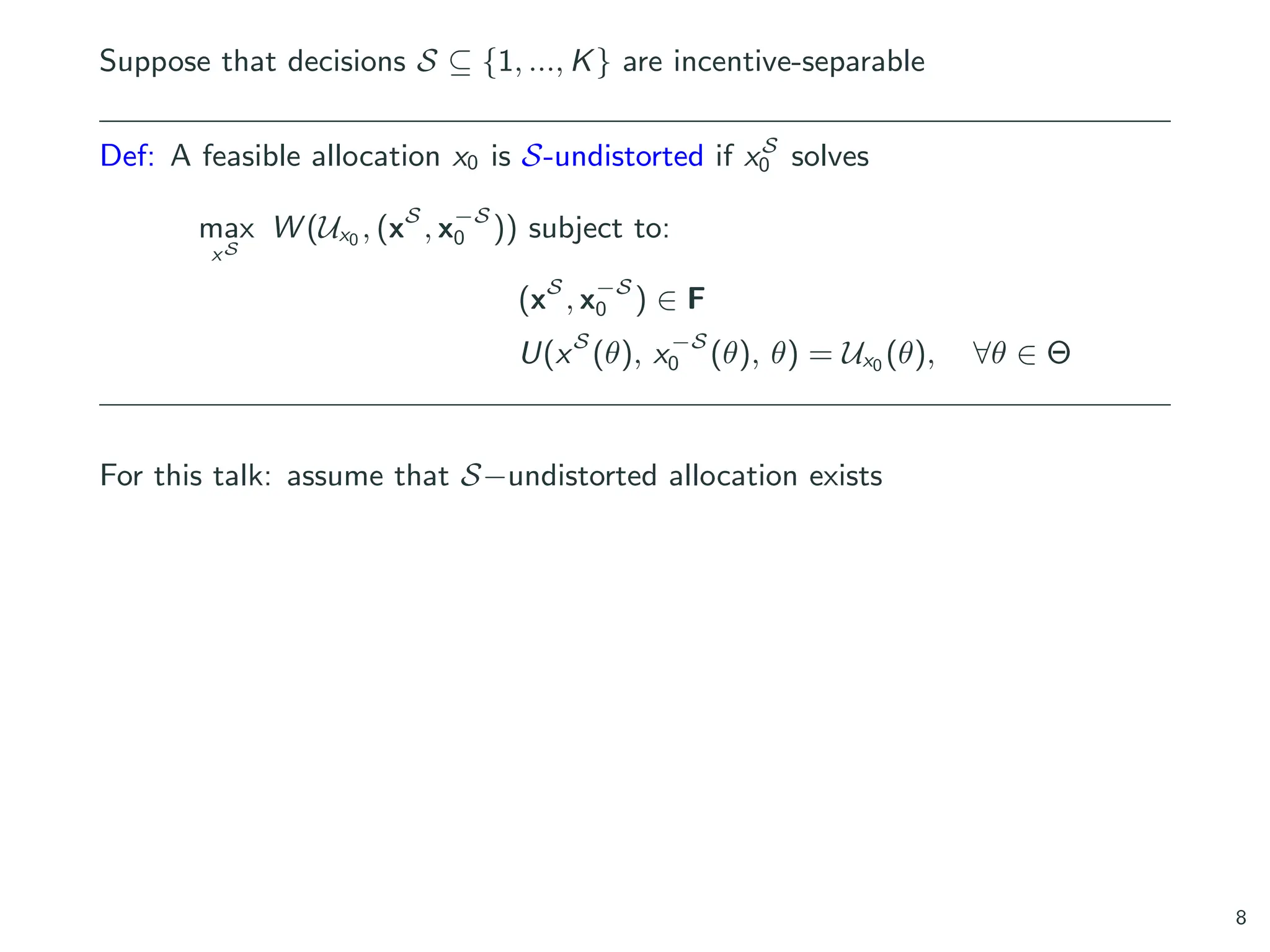

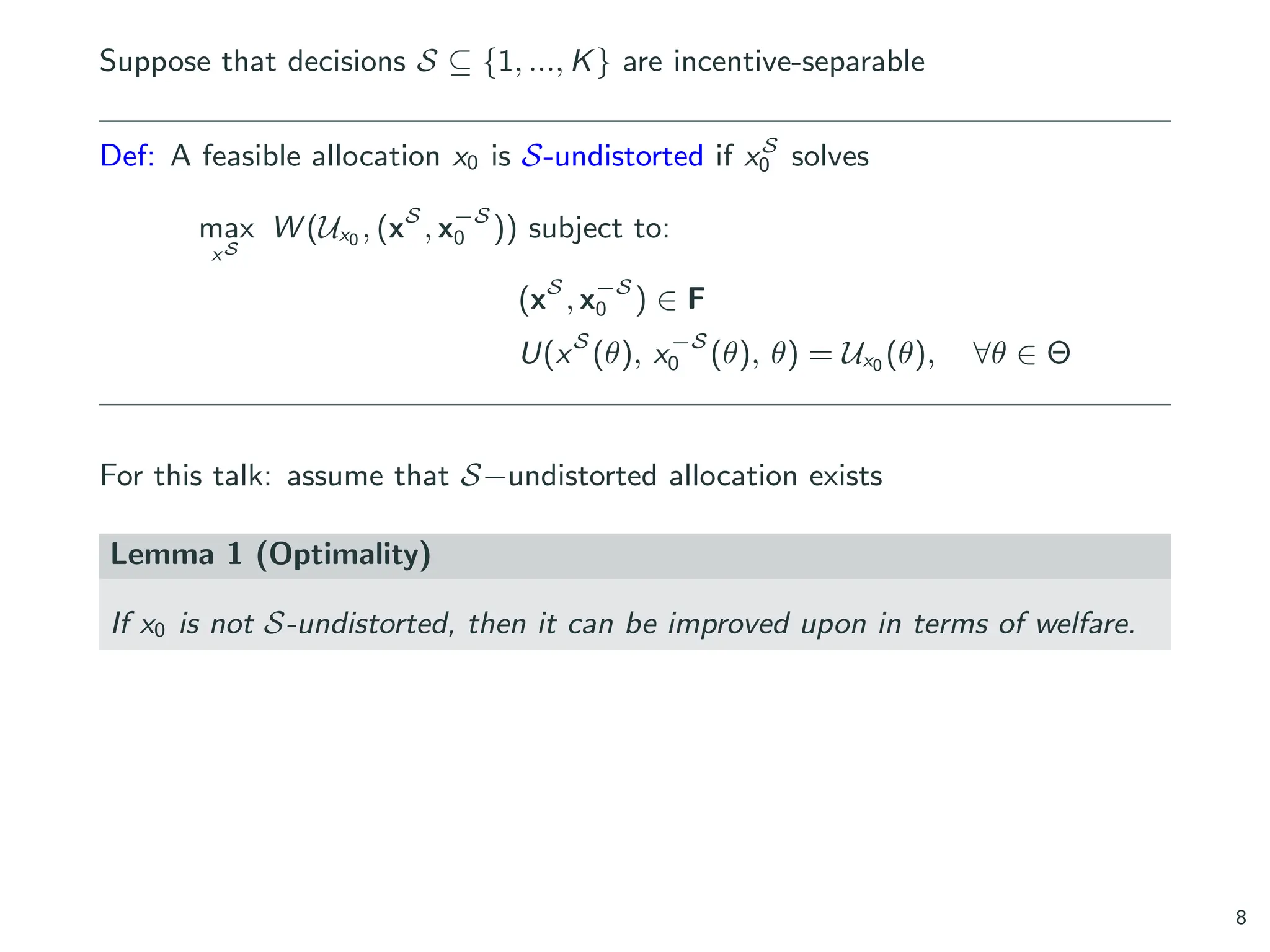

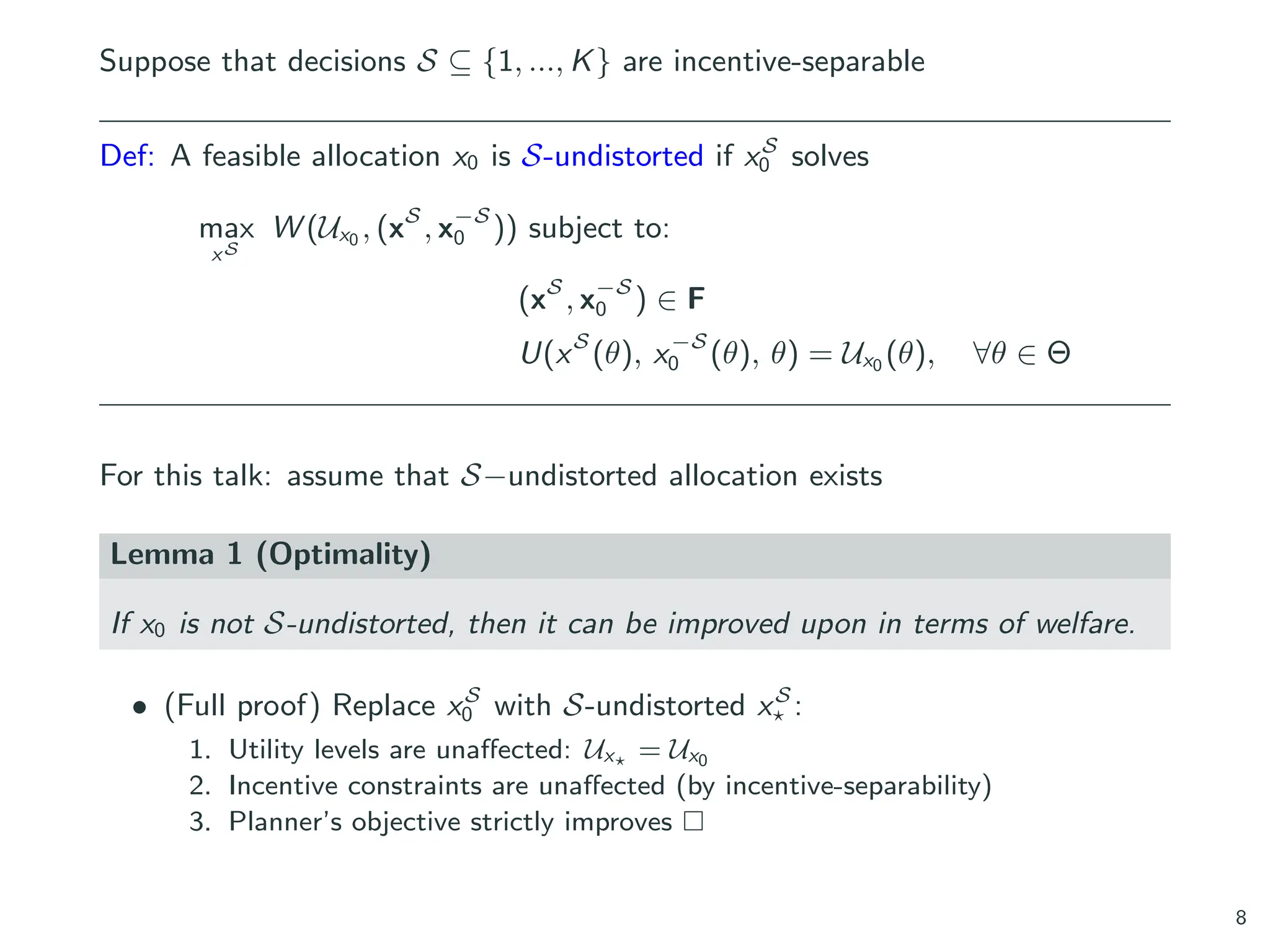

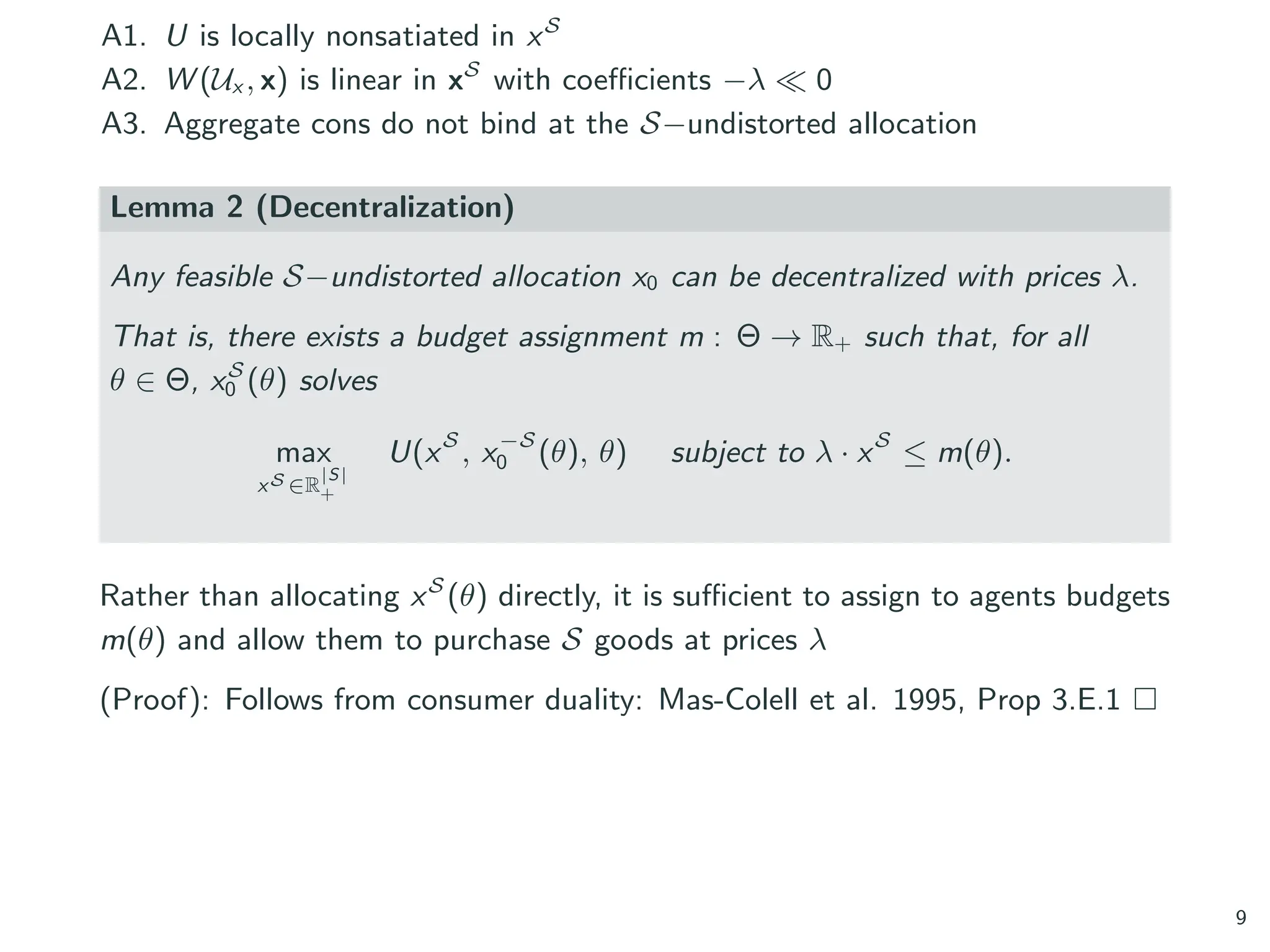

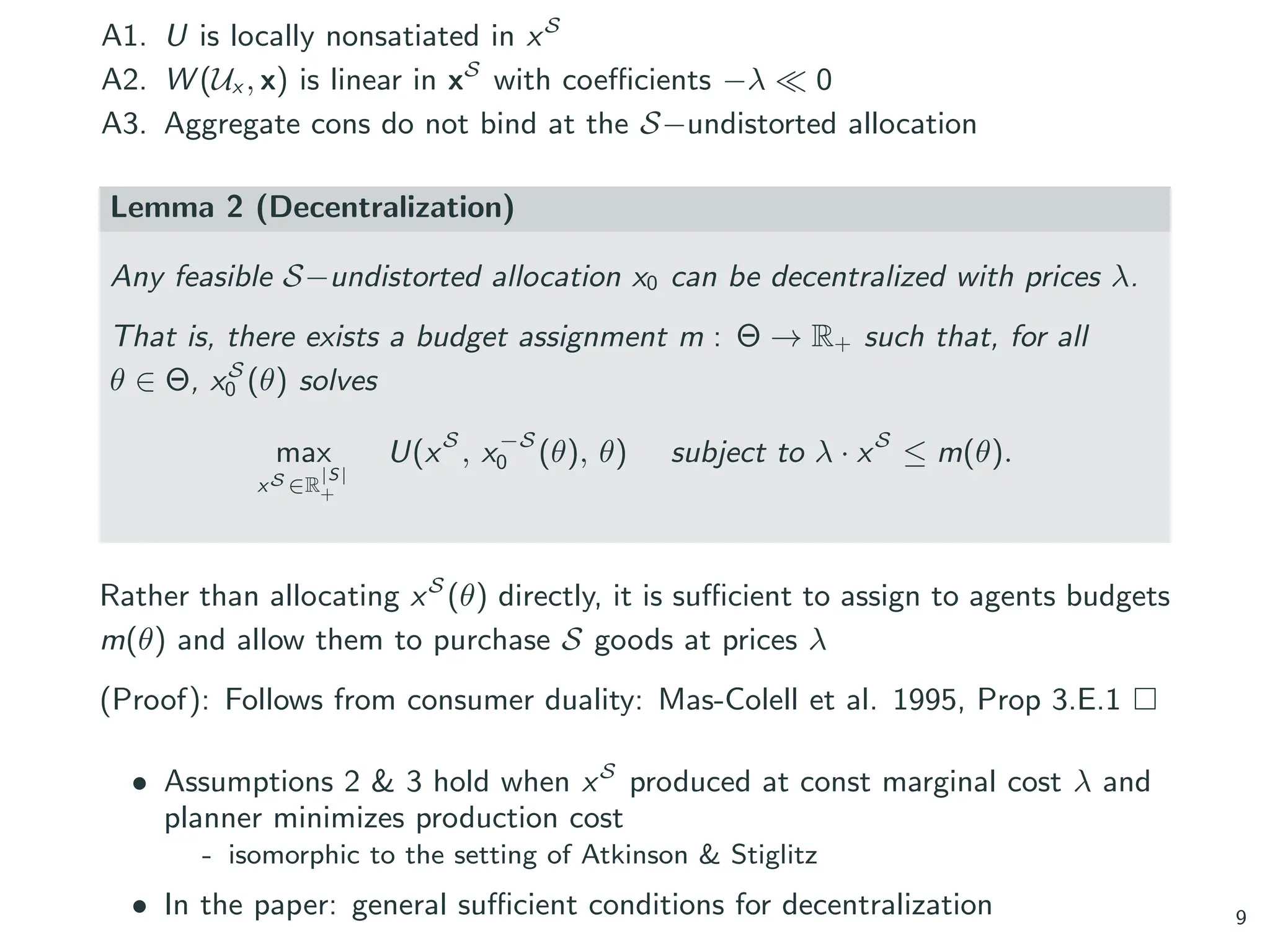

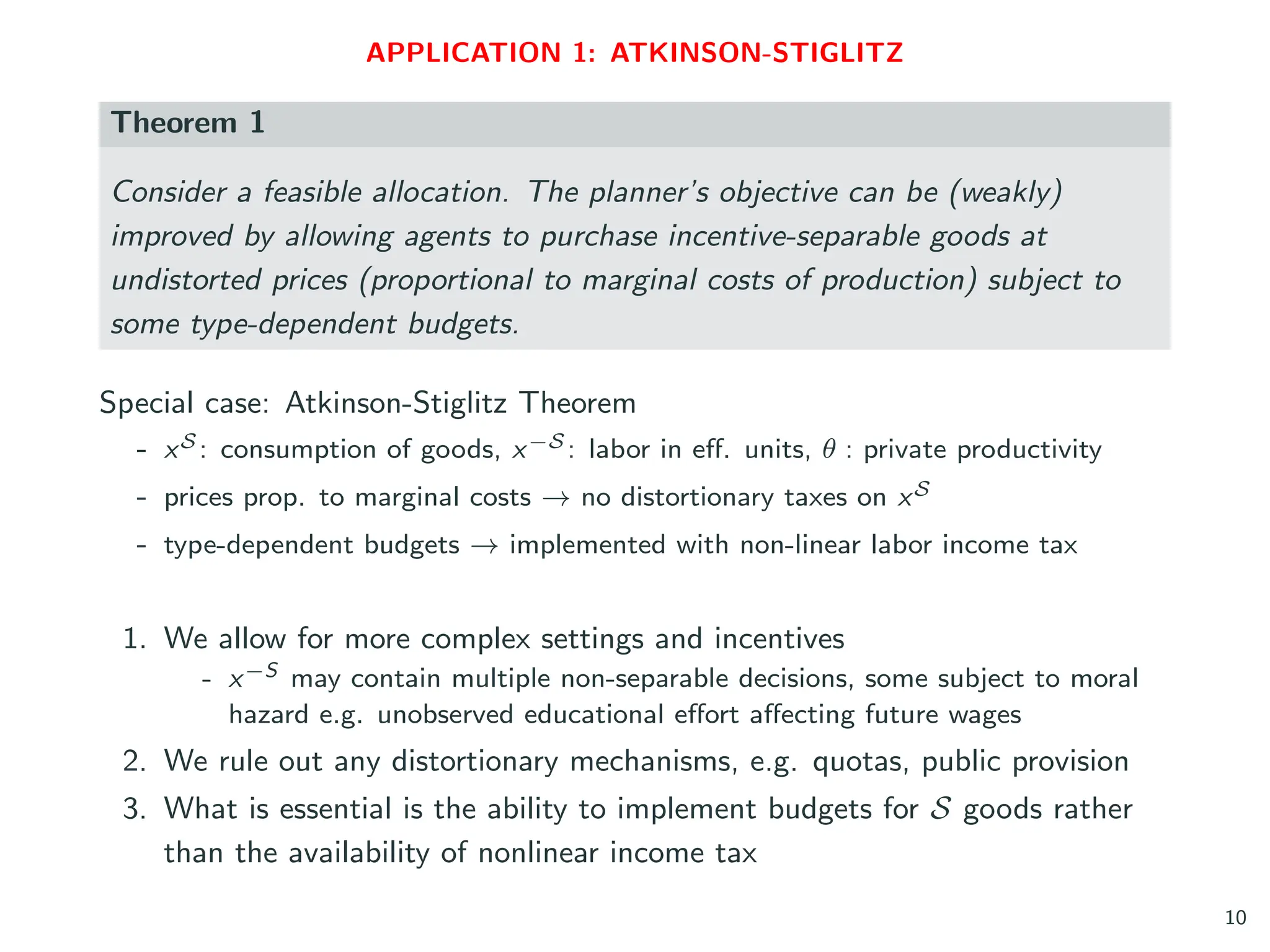

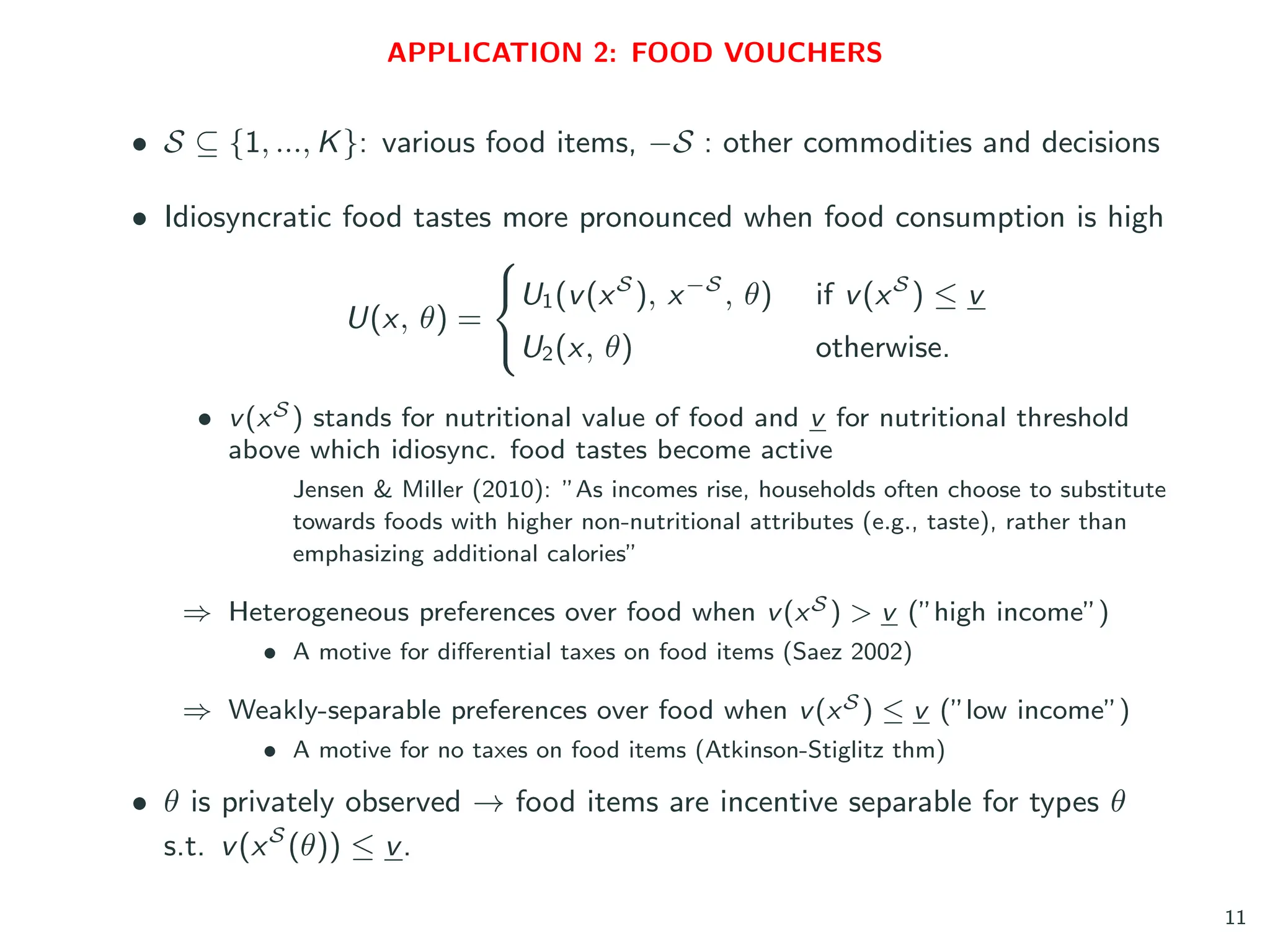

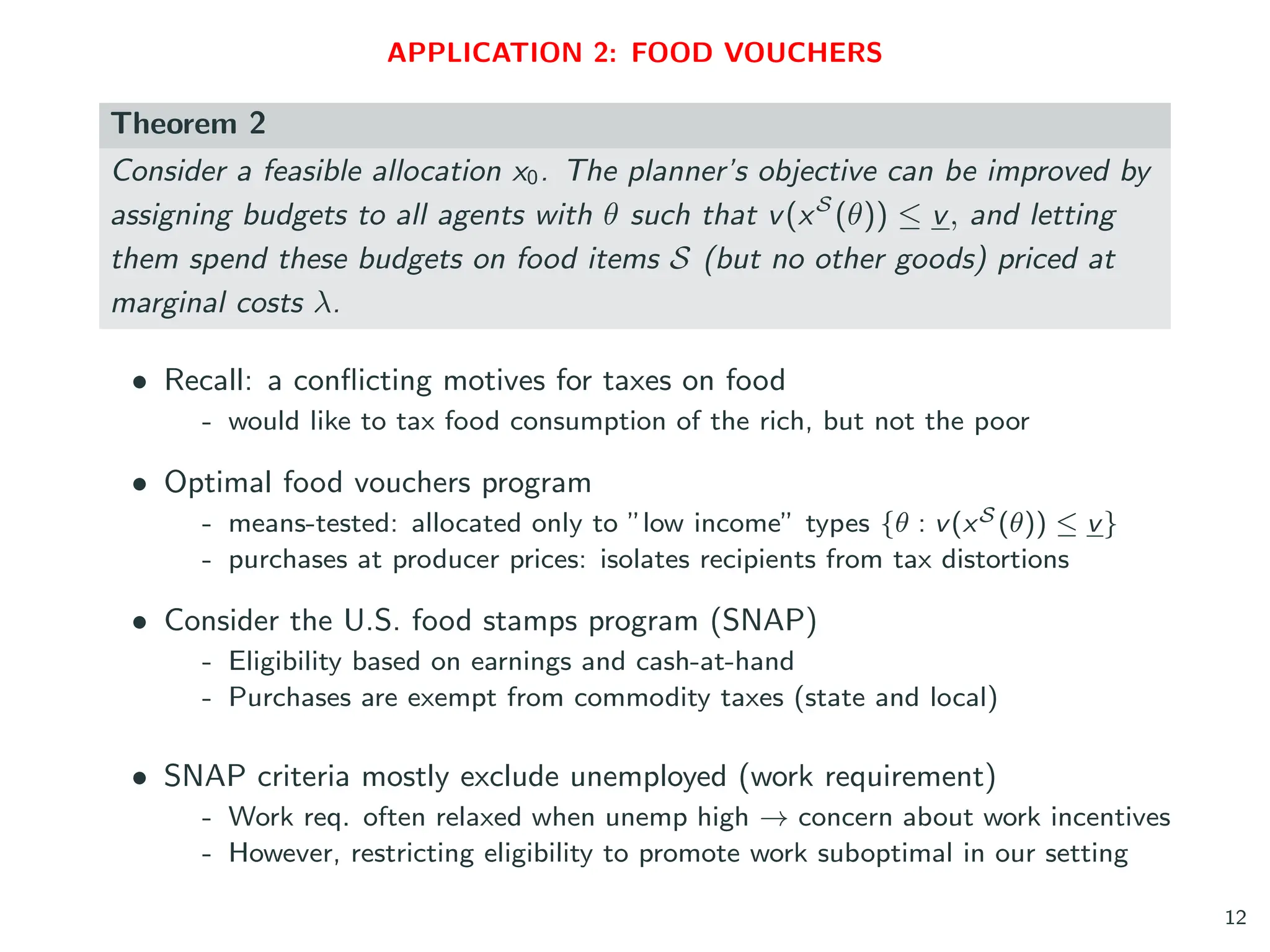

This document summarizes an academic project on incentive separability and optimal redistribution using a mechanism design approach. It discusses how distortions can sometimes be useful for redistribution but sometimes are redundant. It presents a framework for analyzing incentive constraints under private information, moral hazard, and other frictions. Key results shown are that if a set of decisions are incentive-separable, the social planner's objective can be improved by allowing those decisions to be made without distortions, and any optimal and undistorted allocation can be decentralized using prices. Applications discussed include the Atkinson-Stiglitz theorem on non-distortionary commodity taxes and the optimality of food vouchers.

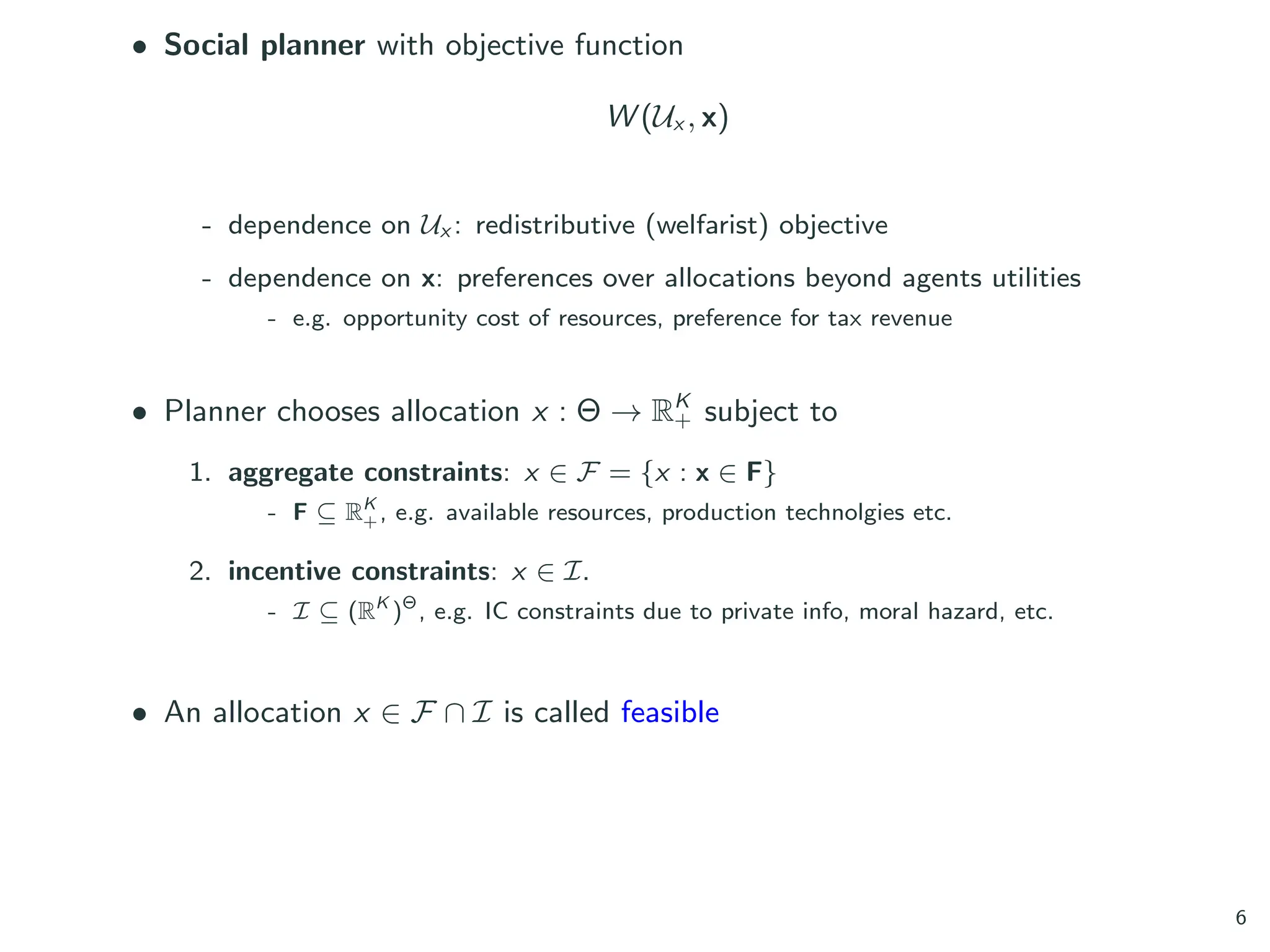

![• A unit mass of agents with types θ ∈ [0, 1] ≡ Θ, uniformly distributed

• Agents’ utility over a vector of K decisions x ∈ RK

+

U (x, θ)

- U continuous in x

- x contains e.g. consumption of goods, labor supply, effort, ...

• An allocation rule x : Θ → RK

+

• associated aggregate allocation: x =

´

x(θ) dθ

• associated utility profile Ux , where Ux (θ) = U(x(θ), θ)

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ddkt-saet-231123142317-e7a9e918/75/DDKT-SAET-pdf-7-2048.jpg)