College Inequality: How Higher Education Has Reinforced Class Divides

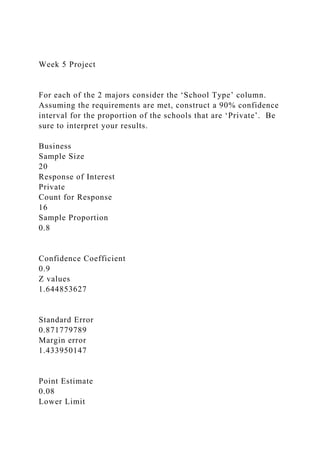

- 1. Week 5 Project For each of the 2 majors consider the ‘School Type’ column. Assuming the requirements are met, construct a 90% confidence interval for the proportion of the schools that are ‘Private’. Be sure to interpret your results. Business Sample Size 20 Response of Interest Private Count for Response 16 Sample Proportion 0.8 Confidence Coefficient 0.9 Z values 1.644853627 Standard Error 0.871779789 Margin error 1.433950147 Point Estimate 0.08 Lower Limit

- 2. -1.353950147 Upper Limit 1.513950147 Engineering Interval Confidence for Proportion Sample Size 20 Response of Interest Private Count for Response 10 Sample Proportion 0.5 Confidence Coefficient 0.9 Z values 1.644854 Standard Error

- 3. 0.689202 Margin error 1.133637 Point Estimate 0.05 Lower Limit -1.08364 Upper Limit 1.183637 For each of the 2 majors construct a 95% confidence interval for the mean of the column ‘Annual % ROI’. Be sure to interpret your results. Business 30 Year ROI Mean 1477800 Standard Error 29727.05661

- 4. Median 1441500 Mode #N/A Standard Deviation 132943.4387 Sample Variance 17673957895 Kurtosis 1.059973389 Skewness 1.313262635 Range 465000 Minimum 1321000 Maximum 1786000 Sum 29556000 Count 20 Confidence Level (95.0%) 62219.44455

- 5. Lower Limit Upper Limit Confidence Interval $1,415,580.56 $1,540,019.44 Engineering 30 Year ROI Mean 1838000 Standard Error 40204.22

- 8. Lower Limit Upper Limit Confidence Interval $1,753,851.61 $1,922,148.39 In this article, Jeffrey J. Williams argues that, contrary to college standing as an open thoroughfare for Americans wanting to improve their lives, it has become a gated toll road primarily available to those from middle-class and upper-class families. Williams is a professor of English and of literary and cultural studies at Carnegie Mellon University. The article was originally published in “Inside Higher Ed” in July of 2016. College and the New Class Divide by Jeffrey J. Williams We usually think of college as providing a boost up the class ladder. That is what it did for a

- 9. generation or more of Americans, particularly from the 1950s through the 1970s. But since around 1980, college has actually calcified class in America. That’s one upshot of Tamara Draut’s new book, Sleeping Giant: How the New Working Class Will Transform America (Doubleday, 2016). She explains how the central divide between the working class and the middle class now is college. Not that things are entirely rosy for those with bachelor’s degrees, but those without degrees have experienced a more severe pinch, with proportionately shrinking wages, degraded conditions, few job protections and general insecurity. Moreover, contrary to college standing as an open thoroughfare for Americans wanting to rise, it has become a gated toll road primarily available to those from middle-class and upper- class families. Those who have gone to college beget those who go to college: if your parents didn’t go to college, you are much more likely to work at or near minimum wage. Only about 9 percent of those from the lowest quartile of wealth complete college degrees, whereas about

- 10. three-quarters from the top quartile do. A key impediment has been the exponential rise of tuition prices since the 1970s, at several times the rate of inflation, correlated with the reduction of public support, which in turn has brought the steep increase in student debt and student work hours. This has produced what Draut called in an earlier essay “The Growing College Gap,” in Inequality Matters: The Growing Economic Divide in America and Its Poisonous Consequences. We usually think that we have seen great progress if not solved the problem of racial inequality, but the enrollment gap between white students and black students was about 5 percent in 1970, whereas it had more than doubled, to 11 percent, in 2000. Similarly, Hispanic students have seen the gap widen from 5 to 13 percent. Affirmative action gets headlines, but we have actually gone backward in attaining racial equality in higher education. One of Draut’s key insights is that the class divide is not just a matter of money but also

- 11. one of culture. As she remarks, “When once a steelworker and an accountant could live on the same block, drive the same car, vacation at the same place and eat at the same restaurants, over the course of the 1980s, 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s” those from higher classes have little substantive contact with those from the working class except when they ring up their groceries or take care of their elderly relatives. That has precipitated a public and political blindness to the new working class, even though it constitutes 60 percent of Americans. Rather than a silent majority, it is an invisible majority. The cultural divide has two daunting consequences. Because those who work in journalism and other news media come from the upper, college- degreed cohort—as Draut adduces, in 1971 only about half of journalists had B.A.s, whereas 92 percent do now—they have little direct sense of the working class. Nor is there a strong interest to represent it in the main news organs, like The New York Times or The

- 12. Washington Post, whose audiences are largely college educated. In Draut’s analysis, after the 2008 crash, about half of the news focused on the banks, a third on the federal response, a fifth on businesses and only a smattering on working-class people who might have lost jobs or their houses. Rather, the Post ran a feature on a banker getting by on a reduction of her salary—to $300,000 a year. Hard times indeed. Similarly, those who work as congressional staffers come almost entirely from college backgrounds. Of high-level staffers, about half “attended private colleges for their undergraduate degree, including 10 percent who went to an Ivy League school.” They are typically the ones who get the internships inside the D.C. beltway, as well as can afford to carry the expenses of internships. That has effectively shut the working class out of public representation or political power, even though it constitutes a majority. For Draut, the key is to

- 13. change the narrative, popping what she calls the “class bubble.” One corrective is simply that we are not all middle class: most Americans are working class. In addition, Sleeping Giant shows that the present working class no longer fits the iconic image of the construction worker in hard hat who had a union to speak for him. Instead, it is largely female, about half Latino and African-American, usually nonunionized, and struggling to make ends meet at or near minimum wage while laboring in home health care, fast food and retail, which have gained the bulk of new jobs. Since college is a key class marker, it’s easy to blame higher education itself as the problem. But for Draut the problem lies in the policies that have drained equal opportunity from it and segregated it, and in turn she advocates policies to enhance public higher education, notably reducing tuition fees and eliminating student debt. [As Draut has said], “Debt-free college is now a real idea and part of the political debate.”

- 14. That’s one salutary reminder we can take from Draut: it might be a long road, but good ideas that seem unrealistic at one moment can win their day. In academic scholarship, we typically focus on conceptual problems, commenting on one and moving onto the next, and in fact we are continually looking for what’s new or next. But in politics, change sometimes seems glacial, and one has to be dogged. It’s useful to keep in mind that massive student debt is only a recent development, arising since the 1980s, and 10 years ago, the idea of abolishing it or enacting free public higher education were considered pie-in-the-sky proposals. But they’re on the agenda now, and we have to keep working to accrue the data, build the narratives and devise policies that aim toward more equality. This article explores how higher education has come to reinforce inequality rather than

- 15. correcting it. The author, Suzanne Mettler, is a professor of government at Cornell University and the author of “Degrees of Inequality: How the Politics of Higher Education Sabotaged the American Dream.” This article was originally published in The New York Times on March 1, 2014. College, the Great Unleveler By Suzanne Mettler When the G.I. Bill of Rights of 1944 made colleges accessible to veterans regardless of socioeconomic background, Robert Maynard Hutchins, the president of the University of Chicago, worried that it would transform elite institutions into “educational hobo jungles.” But the G.I. Bill was only the first of several federal student aid laws that, along with increasing state investment in public universities and colleges, transformed American higher education over the course of three decades from a bastion of privilege into a path toward the American dream.

- 16. Something else began to happen around 1980. College graduation rates kept soaring for the affluent, but for those in the bottom half, a four-year degree is scarcely more attainable today than it was in the 1970s. And because some colleges actually hinder social mobility, what increasingly matters is not just whether you go to college but where. The demise of opportunity through higher education is, fundamentally, a political failure. Our landmark higher education policies have ceased to function effectively, and lawmakers — consumed by partisan polarization and plutocracy — have neglected to maintain and update them. More Americans than ever enroll in college, but the graduates who emerge a few years later indicate that instead of reducing inequality, our system of higher education reinforces it. Three out of four adults who grow up in the top quarter of the income spectrum earn baccalaureate degrees by age 24, but it’s only one out of three in the next quarter down. In the

- 17. bottom half of the economic distribution, it’s less than one out of five for those in the third bracket and fewer than one out of 10 in the poorest. That’s before we even begin differentiating by type of college. Higher education is becoming a caste system, separate and unequal for students with different family incomes. Where students attend college affects their chances of graduating and how indebted they will become in the process. Private nonprofits, schools like Stanford or Vassar, list the highest “sticker prices,” but the average student pays less than half of full fare. Some nonprofits provide generous need-based aid to low- and middle-income students, supplementing their federal aid. Others devote their resources instead to merit-based aid, courting students with high SAT scores, typically from higher-income backgrounds. These colleges rise in the rankings, but they also provide a disadvantage to poorer students who would benefit from more need-based aid, who struggle financially to stay enrolled and who take out more student loans

- 18. to do so. Nearly three-quarters of American college students attend public universities and colleges, historically the nation’s primary channels to educational opportunity. These institutions still offer the best bargain around, yet even there, tuition increases have bred inequality. For those from the richest fifth, the annual cost of attending a public four-year college has inched up from 6 percent of family income in 1971 to 9 percent in 2011. For everyone else, the change is formidable. For those in the poorest fifth, costs at State U have skyrocketed from 42 percent of family income to 114 percent. The worst problems, though, occur at for-profit schools like those run by the Apollo Group (which owns the University of Phoenix), the Education Management Corporation or Corinthian Colleges. These schools cater to low-income students and veterans, but too often they turn hopes for a better life into the despair of financial ruin. Nearly all of their students take out loans to attend, and the

- 19. amounts are staggering. Among holders of bachelor’s degrees, 94 percent borrow. They take on median debt of $33,000 per student, compared with just $18,000 at the nonprofits and $22,000 at the publics. The for- profit graduates have trouble finding jobs that pay enough to afford their debts, and 23 percent of borrowers default within three years, compared with just 7 percent from nonprofits and 8 percent from publics. Just when having a highly educated citizenry is more important than ever, how could we be failing so miserably at achieving it? It’s not as simple as politicians’ terminating laws or gutting funding. Federal student aid has actually increased considerably since 2007. But government has abdicated its leadership role. First, federal student aid has become less effective in promoting opportunity. In the 1970s, the maximum Pell grants for low-income students covered nearly 80 percent of costs at the average four-year public university, but by 2013-14 they covered just 31 percent. Presidents

- 20. beginning with Bill Clinton introduced costly new tax policies to help with tuition, but these have failed to improve access for the less well off. Second, state governments, burdened by the growing cost of Medicaid, K-12 education and prisons, let higher education funding dwindle. Spending per full-time public student fell by an average of 26 percent in real terms between 1990-91 and 2009-10. Besides raising tuition, public colleges have had to squeeze resources at the schools themselves. For poorer students, graduating becomes all the harder as class sizes grow, online courses proliferate and support services are cut. Third, Congress, by loosening regulations, permitted for-profit colleges to thrive on the government’s dime. These schools, which enroll nearly a tenth of college students, use nearly a quarter of federal student aid dollars allocated through Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965, and they account for nearly half of all student loan defaults. A 1998 rule allows them to

- 21. gain up to 90 percent of their revenues from Title IV alone — a figure that does not include their substantial use of military education money. Even during the 2008 financial downturn, the top publicly traded for-profits enjoyed growth. Their upper management and shareholders benefit at the expense of American taxpayers and students. Ordinary young Americans who hoped college could be their route to a better future are the victims of a perfect storm of political winds. It began with existing public policies that required routine maintenance being left to wither. As Nancy Kassebaum, a former Republican senator from Kansas, told me, “Public programs, just like any other programs, need to be managed.” She remembers when bipartisanship functioned well enough to do so on higher education issues. Now Congress is more polarized than at any point in modern history, and it’s not just decisions on nominations and the debt ceiling that suffer. I examined votes on amendments to higher education bills and found that between the 1970s and 1995-2008 the partisan split doubled

- 22. in the House and quadrupled in the Senate. Such division on minor adjustments to policies indicates why Congress has failed to address larger issues. That’s not the whole story, either. Plutocratic governance intensifies the dysfunction, as powerful industries still have the strength to bring politicians together across the aisle in a parody of true bipartisanship. The effect of polarized plutocracy is epitomized by Congress’s support for the for-profit colleges. By the late 1990s, Republican leaders championed the for-profits as the “private sector,” never mind that 15 of the large publicly traded for- profits receive on average 86 percent of their revenues from federal student aid. Plutocracy helped bring House Democrats onboard, as the industry wooed them through strategic lobbying and campaign contributions. The result? In the House of Representatives, where Democrats and Republicans agree on almost nothing, they have united to protect $32 billion taxpayer dollars for the for- profit college industry.

- 23. Most of us were raised to believe that going to college was the surest path to a better life, but for many today that belief can be perilous. Unless we can claw back polarization and plutocracy enough to restore opportunity in higher education, the United States will become a society in which rank is fixed and our ideal of upward mobility but a memory. The following article explores the often overlooked benefits of a higher education. It was originally published in “The Huffington Post” in 2013, and draws its conclusions from a reputable study conducted by the College Board. The author, Lizzie Wann, is the Content Director for Bridgepoint Education, overseeing all website content and working closely with New Media, Career Services, and Student Services for Ashford University. Why Your College Degree Has More Value Than You Think

- 24. By Lizzie Wann We all know about the obvious benefits to having a college degree — namely, a steady job and financial security. But we often overlook other benefits to higher education: quality of life improvements that deserve to be brought into focus, whether you’re on the fence about going back to school or are just having a hard time appreciating the degree you already have. Here are just a few of the benefits you should take into account to start giving college credit where it’s due, according to the College Board’s newly updated study “Education Pays: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society.” Improved Self-Esteem There’s just something about a college grad that makes her stand a little bit straighter and a little bit taller. It likely has to do with the boost to one’s self- esteem and confidence that comes with making it through a higher education program. Studies conducted by the College Board and others like it have

- 25. found that those who have completed additional schooling are not only more well-equipped to handle mental challenges, but also report a higher level of satisfaction when doing so. Since earning a college degree has long been considered a rite of passage, there’s an extra http://www.ashford.edu/ http://blog.brazencareerist.com/2011/09/14/how-useful-is-a- college-degree-these-days/ http://trends.collegeboard.org/education-pays http://trends.collegeboard.org/education-pays http://blog.brazencareerist.com/2013/03/14/the-real-secret-to- career-success-confidence/ sense of accomplishment when you reach the finish line. You’ve accomplished something that no one can ever take away from you. Sure, you can lose the physical piece of paper, and you may move on from the job your degree helped you attain, but you’ll never lose the work behind the journey you undertook to get your diploma. Even when tough times fall, you know you have what it takes to start something and finish it successfully, and that is priceless.

- 26. Healthy Choices In addition to the mental boost that comes with higher education, college grads are healthier overall. Higher socioeconomic status (measured by total family income, level of education attained and professional career status) is directly correlated with better physical health and life expectancy. This correlation seems obvious when you consider that those who earn more money have greater access to health care and healthier food options. But what you may not have considered is that higher education means the ability and desire to make better choices when it comes to habits — eating and otherwise. For example, those with extended educations are less likely to smoke and more likely to exercise. When you put greater emphasis on taking care of your mind with additional schooling, you naturally put greater emphasis on taking care of your body, too. It’s truly as simple as when you know better, you do better.

- 27. Higher Job Satisfaction While we’re on the subject of bettering ourselves, one common reason people seek higher education is to get out of a dead-end job. Having a degree often means having an actual career rather than punching the clock to pay the bills. That’s all fine and good, you may say, but having a career means nothing if you can’t keep it — a task many are finding difficult as of late. Fortunately, a diploma gives you the upper hand when it comes to economy-driven layoffs. Graduates not only have higher job retention rates during a recession, but also an easier time finding re-employment due to higher marketability than their non-graduate colleagues. That means less stress overall during tough economic times. Passing on the Legacy Finally, one of the greatest benefits to having a college education is passing on the legacy to your children. Children of a college grad are more likely to have a better quality of life and

- 28. pursue extended education themselves. Those children also have a much easier time getting into good schools because their parents have emphasized the importance of an education to them. They also tend to have better grades and test scores. As experts often state, children of college grads — even those who don’t attend college themselves — are more motivated to reach for their dreams. They know that their parents pushed through adversity to earn their degrees, and they apply that same philosophy to going after what they want in life — a bar that is placed that much higher by having college-educated parents. Although financial enrichment is one of the main reasons people choose to pursue higher education, there are many other benefits to obtaining that degree. You better yourself through improved self-confidence and enhanced decision-making ability, which also betters the lives of your family members and others around you. http://blog.brazencareerist.com/2013/01/24/why-english-majors- dont-have-to-finish-last/ https://www.luminafoundation.org/about_us/president/speeches/ 2008-05-08.html

- 29. This article was originally published in the January/February issues of The Atlantic, a very highly regarded magazine. The author of the article, Bryan Caplan is an economics professor at George Mason University and the author of The Case Against Education. The World Might Be Better Off Without College for Everyone by Brian Caplan I have been in school for more than 40 years. First preschool, kindergarten, elementary school, junior high, and high school. Then a bachelor’s degree at UC Berkeley, followed by a doctoral program at Princeton. The next step was what you could call my first “real” job— as an economics professor at George Mason University. Thanks to tenure, I have a dream job for life. Personally, I have no reason to lash out at our system of higher education. Yet a lifetime of experience, plus a quarter century of reading and reflection, has convinced me that it is a big waste of time

- 30. and money. When politicians vow to send more Americans to college, I can’t help gasping, “Why? You want us to waste even more?” How, you may ask, can anyone call higher education wasteful in an age when its financial payoff is greater than ever? The earnings premium for college graduates has rocketed to 73 percent—that is, those with a bachelor’s degree earn, on average, 73 percent more than those who have only a high-school diploma, up from about 50 percent in the late 1970s. The key issue, however, isn’t whether college pays, but why. The simple, popular answer is that schools teach students useful job skills. But this dodges puzzling questions. First and foremost: From kindergarten on, students spend thousands of hours studying subjects irrelevant to the modern labor market. Why do English classes focus on literature and poetry instead of business and technical writing? Why do advanced-math classes bother with proofs almost no student can follow? When will the typical student use history? Trigonometry?

- 31. Art? Music? Physics? Latin? The class clown who snarks “What does this have to do with real life?” is onto something. The disconnect between college curricula and the job market has a banal explanation: Educators teach what they know—and most have as little firsthand knowledge of the modern workplace as I do. Yet this merely complicates the puzzle. If schools aim to boost students’ future income by teaching job skills, why do they entrust students’ education to people so detached from the real world? Because, despite the chasm between what students learn and what workers do, academic success is a strong signal of worker productivity. Suppose your law firm wants a summer associate. A law student with a doctorate in philosophy from Stanford applies. What do you infer? The applicant is probably brilliant, diligent, and willing to tolerate serious boredom. If you’re looking for that kind of worker—and what employer isn’t?—you’ll make an offer, knowing full well that nothing the philosopher

- 32. learned at Stanford will be relevant to this job. The labor market doesn’t pay you for the useless subjects you master; it pays you for the preexisting traits you signal by mastering them. This is not a fringe idea. Michael Spence, Kenneth Arrow, and Joseph Stiglitz—all Nobel laureates in economics—made seminal contributions to the theory of educational signaling. Every college student who does the least work required to get good grades silently endorses the theory. But signaling plays almost no role in public discourse or policy making. As a society, we continue to push ever larger numbers of students into ever higher levels of education. The main effect is not better jobs or greater skill levels, but a credentialist arms race. Lest I be misinterpreted, I emphatically affirm that education confers some marketable skills, namely literacy and numeracy. Nonetheless, I believe that signaling accounts for at least half of college’s financial reward, and probably more. Most of the salary payoff for college comes from crossing the graduation finish line.

- 33. Suppose you drop out after a year. You’ll receive a salary bump compared with someone who’s attended no college, but it won’t be anywhere near 25 percent of the salary premium you’d get for a four-year degree. Similarly, the premium for sophomore year is nowhere near 50 percent of the return on a bachelor’s degree, and the premium for junior year is nowhere near 75 percent of that return. Indeed, in the average study, senior year of college brings more than twice the pay increase of freshman, sophomore, and junior years combined. Unless colleges delay job training until the very end, signaling is practically the only explanation. This in turn implies a mountain of wasted resources—time and money that would be better spent preparing students for the jobs they’re likely to do. *** The conventional view—that education pays because students learn—assumes that the typical

- 34. student acquires, and retains, a lot of knowledge. She doesn’t. Teachers often lament summer learning loss: Students know less at the end of summer than they did at the beginning. But summer learning loss is only a special case of the problem of fade-out: Human beings have trouble retaining knowledge they rarely use. Of course, some college graduates use what they’ve learned and thus hold on to it—engineers and other quantitative types, for example, retain a lot of math. But when we measure what the average college graduate recalls years later, the results are discouraging, to say the least. In 2003, the United States Department of Education gave about 18,000 Americans the National Assessment of Adult Literacy. The ignorance it revealed is mind-numbing. Fewer than a third of college graduates received a composite score of “proficient”—and about a fifth were at the “basic” or “below basic” level. You could blame the difficulty of the questions—until you read them. Plenty of college graduates couldn’t make sense of a table explaining how an

- 35. employee’s annual health-insurance costs varied with income and family size, or summarize the work-experience requirements in a job ad, or even use a newspaper schedule to find when a television program ended. Tests of college graduates’ knowledge of history, civics, and science have had similarly dismal results. Of course, college students aren’t supposed to just download facts; they’re supposed to learn how to think in real life. How do they fare on this count? The most focused study of education’s effect on applied reasoning, conducted by Harvard’s David Perkins in the mid- 1980s, assessed students’ oral responses to questions designed to measure informal reasoning, such as “Would a proposed law in Massachusetts requiring a five-cent deposit on bottles and cans significantly reduce litter?” The benefit of college seemed to be zero: Fourth-year students did no better than first-year students. Other evidence is equally discouraging. One researcher tested Arizona State University students’ ability to “apply statistical and methodological concepts to reasoning about everyday-

- 36. life events.” In the researcher’s words: Of the several hundred students tested, many of whom had taken more than six years of laboratory science … and advanced mathematics through calculus, almost none demonstrated even a semblance of acceptable methodological reasoning. Those who believe that college is about learning how to learn should expect students who study science to absorb the scientific method, then habitually use it to analyze the world. This scarcely occurs. College students do hone some kinds of reasoning that are specific to their major. One ambitious study at the University of Michigan tested natural- science, humanities, and psychology and other social-science majors on verbal reasoning, statistical reasoning, and conditional reasoning during the first semester of their first year. When the same students were retested the second semester of their fourth year, each group had sharply improved in precisely

- 37. one area. Psychology and other social-science majors had become much better at statistical reasoning. Natural-science and humanities majors had become much better at conditional reasoning—analyzing “if … then” and “if and only if” problems. In the remaining areas, however, gains after three and a half years of college were modest or nonexistent. The takeaway: Psychology students use statistics, so they improve in statistics; chemistry students rarely encounter statistics, so they don’t improve in statistics. If all goes well, students learn what they study and practice. Actually, that’s optimistic. Educational psychologists have discovered that much of our knowledge is “inert.” Students who excel on exams frequently fail to apply their knowledge to the real world. Take physics. As the Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner writes, Students who receive honor grades in college-level physics courses are frequently unable to solve basic problems and questions encountered in a form slightly different from that

- 38. on which they have been formally instructed and tested. The same goes for students of biology, mathematics, statistics, and, I’m embarrassed to say, economics. I try to teach my students to connect lectures to the real world and daily life. My exams are designed to measure comprehension, not memorization. Yet in a good class, four test- takers out of 40 demonstrate true economic understanding. *** Economists’ educational bean counting can come off as annoyingly narrow. Non-economists— also known as normal human beings—lean holistic: We can’t measure education’s social benefits solely with test scores or salary premiums. Instead we must ask ourselves what kind of society we want to live in—an educated one or an ignorant one? Normal human beings make a solid point: We can and should investigate education’s broad social implications. When humanists consider my calculations of education’s returns, they

- 39. assume I’m being a typical cynical economist, oblivious to the ideals so many educators hold dear. I am an economist and I am a cynic, but I’m not a typical cynical economist. I’m a cynical idealist. I embrace the ideal of transformative education. I believe wholeheartedly in the life of the mind. What I’m cynical about is people. I’m cynical about students. The vast majority are philistines. I’m cynical about teachers. The vast majority are uninspiring. I’m cynical about “deciders”—the school officials who control what students study. The vast majority think they’ve done their job as long as students comply. Those who search their memory will find noble exceptions to these sad rules. I have known plenty of eager students and passionate educators, and a few wise deciders. Still, my 40 years in the education industry leave no doubt that they are hopelessly outnumbered. Meritorious education survives but does not thrive. Indeed, today’s college students are less willing than those of previous generations to do

- 40. the bare minimum of showing up for class and temporarily learning whatever’s on the test. Fifty years ago, college was a full-time job. The typical student spent 40 hours a week in class or studying. Effort has since collapsed across the board. “Full time” college students now average 27 hours of academic work a week—including just 14 hours spent studying. What are students doing with their extra free time? Having fun. As Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa frostily remark in their 2011 book, Academically Adrift, If we presume that students are sleeping eight hours a night, which is a generous assumption given their tardiness and at times disheveled appearance in early morning classes, that leaves 85 hours a week for other activities. Arum and Roksa cite a study finding that students at one typical college spent 13 hours a week studying, 12 hours “socializing with friends,” 11 hours “using computers for fun,” eight hours working for pay, six hours watching TV, six hours exercising, five hours on “hobbies,” and three hours on “other forms of entertainment.” Grade inflation

- 41. completes the idyllic package by shielding students from negative feedback. The average GPA is now 3.2. *** What does this mean for the individual student? Would I advise an academically well-prepared 18-year-old to skip college because she won’t learn much of value? Absolutely not. Studying irrelevancies for the next four years will impress future employers and raise her income potential. If she tried to leap straight into her first white-collar job, insisting, “I have the right stuff to graduate, I just choose not to,” employers wouldn’t believe her. To unilaterally curtail your education is to relegate yourself to a lower-quality pool of workers. For the individual, college pays. This does not mean, however, that higher education paves the way to general prosperity or social justice. When we look at countries around the world, a year of education appears to

- 42. raise an individual’s income by 8 to 11 percent. By contrast, increasing education across a country’s population by an average of one year per person raises the national income by only 1 to 3 percent. In other words, education enriches individuals much more than it enriches nations. How is this possible? Credential inflation: As the average level of education rises, you need more education to convince employers you’re worthy of any specific job. One research team found that from the early 1970s through the mid‑1990s, the average education level within 500 occupational categories rose by 1.2 years. But most of the jobs didn’t change much over that span—there’s no reason, except credential inflation, why people should have needed more education to do them in 1995 than in 1975. What’s more, all American workers’ education rose by 1.5 years in that same span—which is to say that a great majority of the extra education workers received was deployed not to get better jobs, but to get jobs that had recently been held by people with less education.

- 43. As credentials proliferate, so do failed efforts to acquire them. Students can and do pay tuition, kill a year, and flunk their finals. Any respectable verdict on the value of education must account for these academic bankruptcies. Failure rates are high, particularly for students with low high-school grades and test scores; all told, about 60 percent of full-time college students fail to finish in four years. Simply put, the push for broader college education has steered too many students who aren’t cut out for academic success onto the college track. The college-for-all mentality has fostered neglect of a realistic substitute: vocational education. It takes many guises—classroom training, apprenticeships and other types of on-the- job training, and straight-up work experience—but they have much in common. All vocational education teaches specific job skills, and all vocational education revolves around learning by doing, not learning by listening. Research, though a bit sparse, suggests that vocational education raises pay, reduces unemployment, and increases the rate of

- 44. high-school completion. Defenders of traditional education often appeal to the obscurity of the future. What’s the point of prepping students for the economy of 2018, when they’ll be employed in the economy of 2025 or 2050? But ignorance of the future is no reason to prepare students for occupations they almost surely won’t have—and if we know anything about the future of work, we know that the demand for authors, historians, political scientists, physicists, and mathematicians will stay low. It’s tempting to say that students on the college track can always turn to vocational education as a Plan B, but this ignores the disturbing possibility that after they crash, they’ll be too embittered to go back and learn a trade. The vast American underclass shows that this disturbing possibility is already our reality. Education is so integral to modern life that we take it for granted. Young people have to leap through interminable academic hoops to secure their place in the adult world. My thesis, in a single sentence: Civilized societies revolve around education now, but there is a better—indeed,

- 45. more civilized—way. If everyone had a college degree, the result would be not great jobs for all, but runaway credential inflation. Trying to spread success with education spreads education but not success. Midterm Exam: Summary & Response *Take-home exam: 100 Homework Points *Required length: About 750 Words. Topic: Higher Education Background: You have spent the past three weeks developing a deeply informed opinion about the purpose of higher education. You’ve explored your own experiences, interviewed college graduates, read a variety of texts, debated the purpose of higher education in class, and constructed an argument about higher education based on a synthesis of these wide-ranging sources. In short, you know what you’re talking about. You have a certain amount of expertise on this topic. You are going to use that expertise to respond to the arguments of a published author. Main Task:First, summarize the argument made in either "The Value of a College Degree" or "The Case Against College." Then in a clear, arguable thesis statement, state your response to that argument. Explain and support your response with 2-3 proof paragraphs. Finally, conclude the essay with a paragraph exploring the broader significance of your argument. Important Notes * You are taking advantage of the hard work you’ve already done in this unit in order to respond to the writer’s argument with cogency and force. Therefore, do not worry if there is some redundancy between the essay you just completed and this in-class essay.

- 46. * Notice that this assignment is asking you to write the exact same type of essay as Essay #1—summary and response. Use what you learned writing that essay to make this one excellent. Also, apply my feedback on your first essay to this essay. * You are bringing in evidence from the other readings, your experience, your interview, etc. in order to prove the writer of “The Value of a College Degree” or “The Case Against College” right or wrong. Structure Introduction (1 paragraph): Set up the conversation, and thoroughly summarize the main points from the text you will be responding to. (Use the strategies described in Ch. 2 of TSIS.) Thesis (1-2 sentences): State your response to the arguments summarized in the introduction—agree, disagree, or both. (Use the templates in Ch. 4 of TSIS.) Proof (2-3 paragraphs):Back up your response with reasoning and evidence. · Point: State one reason you agree/disagree with one of the writer’s ideas. ("I agree with the point that_____ because ____.") · Information, part 1: Briefly review the specific idea from the text you’re responding to. · Information, part 2: Provide evidence from your experience, your interview, the previous readings from this unit, etc. that proves the writer is wrong or right. · Explanation: Explain why your evidence proves the writer right or wrong. Conclusion (1 paragraph):What is significant about what you’ve covered in this essay? How does this argument affect the reader? What bigger issues or problems do your points in this essay shed light on? Essay Goals: These goals will be incorporated into the grading

- 47. criteria for the essay. 1. The introduction includes a summary that accurately represents the writer's ideas and demonstrates your comprehension of the text. 2. The introduction's summary is relevant to the response that follows. The summary highlights the features of the text that the rest of the essay responds to. 3. The thesisclearly communicates your response to the writer’s ideas. 4. The thesis prepares the reader, previewing the full scope and content of the essay. 5. All of the proof paragraphs have a clear connection to the thesis, creating a unified essay. 6. All of the proof paragraphs have topic sentences that preview the content of the paragraph and evidence that proves the claim made in the topic sentence. 7. The conclusion answers the question, “so what?” It explains the “big picture” implications of your essay. 8. The essay is carefully proofread. Itis mostly free of grammatical and mechanical errors. 9. The response, as a whole, "joins the conversation," engages directly and meaningfully with the writer's ideas while also bringing something new to the debate. PAGE 43

- 48. Business MajorSchool TypeCost30 Year ROIAnnual ROIPrivate$222,700.00$1,786,000.007.70%SUMMARY OUTPUTPrivate$176,400.00$1,758,000.008.40%Private$212,20 0.00$1,714,000.007.80%Regression StatisticsPublic$125,100.00$1,535,000.009.10%Multiple R0.9787209512Private$212,700.00$1,529,000.007.40%R Square0.9578947004Public$92,910.00$1,501,000.0010.10%Adj usted R Square0.955417918Private$214,900.00$1,485,000.007.30%Stan dard Error0.0023845146Private$217,800.00$1,483,000.007.20%Obse rvations19Private$225,600.00$1,444,000.007.00%Private$217,3 00.00$1,442,000.007.10%ANOVAPrivate$226,500.00$1,441,00 0.007.00%dfSSMSFSignificance FPrivate$215,500.00$1,438,000.007.20%Regression10.0021990 2370.0021990237386.74965023190Private$223,500.00$1,428,0 00.007.00%Residual170.00009666050.0000056859Private$226, 600.00$1,414,000.007.00%Total180.0022956842Private$189,30 0.00$1,397,000.007.50%Public$89,700.00$1,382,000.009.90%C oefficientsStandard Errort StatP-valueLower 95%Upper 95%Lower 95.0%Upper 95.0%Public$87,030.00$1,376,000.0010.00%Intercept0.118574 67940.00212155455.89048346911.03615220115437E- 200.11409859170.12305076710.11409859170.1230507671Priva te$218,200.00$1,343,000.006.90%222700- 0.00000021580.000000011-19.66595154660-0.0000002389- 0.0000001926-0.0000002389- 0.0000001926Private$229,900.00$1,339,000.006.70%Private$1 48,800.00$1,321,000.008.10%Best College ROI by Majo 2013: Payscale.comRESIDUAL OUTPUTObservationPredicted 0.077Residuals10.08051541770.003484582320.07279137250.00 5208627530.0915836724- 0.000583672440.07268349480.001316505250.09852884040.002 471159660.07220883280.000791167270.0715831420.00041685 880.06990024950.000099750590.0716910197- 0.0006910197100.06970606960.0002939304110.0720793795-

- 49. 0.0000793795120.0703533359- 0.0003533359130.0696844940.000315506140.0777321724- 0.0027321724150.0992214154- 0.0002214154160.09979748240.0002025176170.0714968398- 0.0024968398180.068972501-0.001972501190.0864702682- 0.0054702682 222700 Line Fit Plot 176400 212200 125100 212700 92910 214900 217800 225600 217300 226500 215500 223500 226600 189300 89700 87030 218200 229900 148800 8.4000000000000005E-2 7.8E-2 9.0999999999999998E-2 7.3999999999999996E-2 0.10100000000000001 7.2999999999999995E-2 7.1999999999999995E-2 7.0000000000000007E-2 7.0999999999999994E-2 7.0000000000000007E-2 7.1999999999999995E-2 7.0000000000000007E-2 7.0000000000000007E-2 7.4999999999999997E-2 9.9000000000000005E-2 0.1 6.9000000000000006E-2 6.7000000000000004E-2 8.1000000000000003E-2 Predicted 0.077 176400 212200 125100 212700 92910 214900 217800 225600 217300 226500 215 500 223500 226600 189300 89700 87030 218200 229900 148800 8.051541770169697E-2 7.2791372523244413E-2 9.1583672384786791E-2 7.2683494797288389E-2 9.8528840381836708E-2 7.2208832803081796E-2 7.1583141992536764E-2 6.9900249467622522E-2 7.1691019718492802E-2 6.970606956090164E-2 7.2079379531934551E-2 7.0353335916637894E-2 6.9684494015710446E-2 7.7732172372031103E-2 9.9221415382474504E-2 9.9797482439079765E-2 7.1496839811771934E-2 6.8972501024400557E-2 8.6470268174470427E-2 222700 0.077 Engineering MajorSchool TypeCost30 Year ROIAnnual ROIPrivate$221,700.00$2,412,000.008.70%SUMMARY

- 50. OUTPUTPrivate$213,000.00$2,064,000.008.30%Private$230,10 0.00$1,949,000.007.90%Regression StatisticsPrivate$222,600.00$1,947,000.008.00%Multiple R0.9837243039Private$225,800.00$1,938,000.008.00%R Square0.9677135062Public$87,660.00$1,937,000.0011.20%Adj usted R Square0.9658143007Private$224,900.00$1,915,000.007.90%Sta ndard Error0.002766586Private$221,600.00$1,878,000.007.90%Obser vations19Public$125,100.00$1,854,000.009.80%Private$215,70 0.00$1,794,000.007.90%ANOVAPublic$92,530.00$1,761,000.0 010.60%dfSSMSFSignificance FPrivate$217,800.00$1,752,000.007.70%Regression10.0038999 8730.0038999873509.53595942710Public$89,700.00$1,727,000 .0010.70%Residual170.0001301180.000007654Private$229,600. 00$1,716,000.007.50%Total180.0040301053Public$101,500.00$ 1,703,000.0010.20%Public$115,500.00$1,694,000.009.70%Coef ficientsStandard Errort StatP-valueLower 95%Upper 95%Lower 95.0%Upper 95.0%Public$104,500.00$1,690,000.0010.10%Intercept0.12731 286620.001701214474.83645998097.3896489481079E- 230.12372361750.13090211490.12372361750.1309021149Publi c$69,980.00$1,685,000.0011.50%221700- 0.00000022040.0000000098-22.57290321220-0.000000241- 0.0000001998-0.000000241- 0.0000001998Private$219,400.00$1,676,000.007.60%Public$64 ,930.00$1,668,000.0011.70%RESIDUAL OUTPUTObservationPredicted 0.087Residuals10.08037475970.002625240320.07660648910.00 2393510930.07825923940.001740760640.07755406590.002445 934150.10799552150.004004478560.0777523960.00124760470. 07847960610.000520393980.0997449923- 0.001744992390.0797797696-0.0007797696100.1069223357- 0.0009223357110.0793169995-0.0023169995120.1075459734- 0.0005459734130.0767166725-0.0017166725140.1049456464- 0.0029456464150.1018605126-0.0048605126160.1042845463-

- 51. 0.0032845463170.11189160470.0031083953180.0789644128- 0.0029644128190.11300445650.0039955435 213000 230100 222600 225800 87660 224900 221600 125100 215700 92530 217800 89700 229600 101500 115500 104500 69980 219400 64930 8.3000000000000004E-2 7.9000000000000001E-2 0.08 0.08 0.112 7.9000000000000001E-2 7.9000000000000001E-2 9.8000000000000004E-2 7.9000000000000001E-2 0.106 7.6999999999999999E-2 0.107 7.4999999999999997E-2 0.10199999999999999 9.7000000000000003E-2 0.10100000000000001 0.115 7.5999999999999998E-2 0.11700000000000001 Predicted 0.087 213000 230100 222600 225800 87660 224900 221600 125100 215700 92530 217800 89700 229600 101500 115500 104500 69980 219400 64930 8.0374759655289965E-2 7.6606489131244959E-2 7.825923936108925E-2 7.7554065929689026E-2 0.10799552149644798 7.7752395957270348E-2 7.8479606058401832E-2 9.9744992349065198E-2 7.9779769572546011E-2 0.10692233568053573 7.9316999508189615E-2 0.10754597343393033 7.6716672479901243E-2 0.10494564640564194 0.10186051264326591 0.10428454631370423 0.11189160470493427 7.8964412792489502E-2 0.11300445652636278 Week 6 Project Engineering Hypothesis Test Sample Size 21 Sample Mean $164,680.00 Sample Standard Deviation 66385.12191 Hypothesized Value 160000

- 52. Standard Error 14486.42125 Test Statistics t 0.323061156 Degree of Freedom 20 p-value (lower tail) 0.624998872 0.5 p-value (upper tail) 0.375001128 p-value (two tail) 0.750002255 The level of 0.05 does not reject the null hypothesis in conclusion because the mean ‘Cost’ for a college for Business Major is not any dissimilar than $160,000 Major Hypothesis Test Sample Size 20 Sample Mean $188,632.00 Sample standard Deviation 50503.42902 Hypothesized Value 160000 Standard Error 11292.91004 Test Statistic t 2.535396094 Degree of Freedom 19 p-value (lower tail) 0.98991306 0.05 p-value (upper tail) 0.01008694 p-value(two tail) 0.020173879 We should reject the null hypothesis, that is to say, the mean ‘Cost’ for Business major is not $160,000 t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances 1786000 2412000

- 53. Mean 1461578.947 1807789.474 Variance 13101035088 14855953216 Observations 19 19 Hypothesized Mean Difference 0 df 36 t Stat -9.025512588 P(T<=t) one-tail 4.46406E-11 t Critical one-tail 1.305513886 P(T<=t) two-tail 8.92812E-11 t Critical two-tail 1.688297714 The 30 year ROI for Business is less than the 30 year ROI for engineering. Sheet4Row LabelsCount of Annual ROI(blank)0.067- 0.077130.077-0.08730.087-0.09710.097-0.1073Grand Total20 Histogram

- 54. Total (blank) 0.067-0.077 0.077-0.087 0.087-0.097 0.097-0.107 13 3 1 3 Business MajorSchool TypeCost30 Year ROIAnnual ROIPrivate$222,700.00$1,786,000.007.70%Private$176,400.00 $1,758,000.008.40%Private$212,200.00$1,714,000.007.80%Pub lic$125,100.00$1,535,000.009.10%Private$212,700.00$1,529,0 00.007.40%Public$92,910.00$1,501,000.0010.10%Private$214, 900.00$1,485,000.007.30%Private$217,800.00$1,483,000.007.2 0%Private$225,600.00$1,444,000.007.00%Private$217,300.00$ 1,442,000.007.10%Private$226,500.00$1,441,000.007.00%Priva te$215,500.00$1,438,000.007.20%Private$223,500.00$1,428,00 0.007.00%Private$226,600.00$1,414,000.007.00%Private$189,3 00.00$1,397,000.007.50%Public$89,700.00$1,382,000.009.90% Public$87,030.00$1,376,000.0010.00%Private$218,200.00$1,34 3,000.006.90%Private$229,900.00$1,339,000.006.70%Private$1 48,800.00$1,321,000.008.10%Best College ROI by Majo 2013: Payscale.comMean7.82%Median7.35% Sheet2Row LabelsCount of Annual ROI0.075-0.085100.085- 0.09510.095-0.10540.105-0.11530.115-0.1252Grand Total20 Histogram Total 0.075-0.085 0.085-0.095 0.095-0.105 0.105- 0.115 0.115-0.125 10 1 4 3 2 Engineering MajorSchool TypeCost30 Year ROIAnnual ROIPrivate$221,700.00$2,412,000.008.70%Private$213,000.00 $2,064,000.008.30%Private$230,100.00$1,949,000.007.90%Priv ate$222,600.00$1,947,000.008.00%Private$225,800.00$1,938,0

- 55. 00.008.00%Public$87,660.00$1,937,000.0011.20%Private$224, 900.00$1,915,000.007.90%Private$221,600.00$1,878,000.007.9 0%Public$125,100.00$1,854,000.009.80%Private$215,700.00$1 ,794,000.007.90%Public$92,530.00$1,761,000.0010.60%Private $217,800.00$1,752,000.007.70%Public$89,700.00$1,727,000.00 10.70%Private$229,600.00$1,716,000.007.50%Public$101,500. 00$1,703,000.0010.20%Public$115,500.00$1,694,000.009.70%P ublic$104,500.00$1,690,000.0010.10%Public$69,980.00$1,685, 000.0011.50%Private$219,400.00$1,676,000.007.60%Public$64 ,930.00$1,668,000.0011.70%Mean9.15%Median8.50% Week 2 For each of the 2 majors calculate the mean, median, minimum, maximum, range, and standard deviation for the columns ‘Cost’ and ’30-Year ROI Engineering Major Minimum $64,930.00 Maximum $230,100.00 Mean $164,680.00 Median $214,350.00 Standard Dev $66,385.12 Range $165,170.00 Business Major Minimum $87,030.00 Maximum $229,900.00 Mean $188,632.00 Median $215,200.00 Standard Dev $50,503.43 Range $142,870.00 By hand or with Excel, for each of the 2 majors calculate the probability that a college picked from the column for ‘School Type’ is ‘Private’.

- 56. Engineering 11÷20=0.55=55 Business 16÷20=0.80=80 By hand or with Excel, for each of the 2 majors find the probability that a college with the ‘School Type’ ‘Private’ has a ’30-Year ROI’ between $1,500,000 and $1,800,000. Engineering 4÷11=0.36=36 Business 4÷16=.025=25