FMLA Leave Denied for Vegas Trip

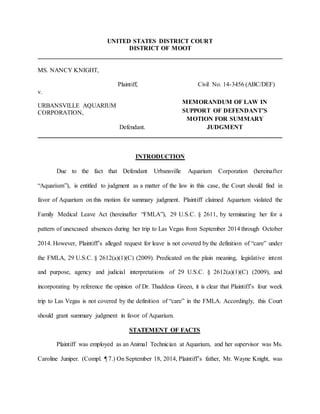

- 1. UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MOOT ______________________________________________________________________________ MS. NANCY KNIGHT, Plaintiff, Civil No. 14-3456 (ABC/DEF) v. URBANSVILLE AQUARIUM CORPORATION, Defendant. ______________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Due to the fact that Defendant Urbansville Aquarium Corporation (hereinafter “Aquarium”), is entitled to judgment as a matter of the law in this case, the Court should find in favor of Aquarium on this motion for summary judgment. Plaintiff claimed Aquarium violated the Family Medical Leave Act (hereinafter “FMLA”), 29 U.S.C. § 2611, by terminating her for a pattern of unexcused absences during her trip to Las Vegas from September 2014 through October 2014. However, Plaintiff’s alleged request for leave is not covered by the definition of “care” under the FMLA, 29 U.S.C. § 2612(a)(1)(C) (2009). Predicated on the plain meaning, legislative intent and purpose, agency and judicial interpretations of 29 U.S.C. § 2612(a)(1)(C) (2009), and incorporating by reference the opinion of Dr. Thaddeus Green, it is clear that Plaintiff’s four week trip to Las Vegas is not covered by the definition of “care” in the FMLA. Accordingly, this Court should grant summary judgment in favor of Aquarium. STATEMENT OF FACTS Plaintiff was employed as an Animal Technician at Aquarium, and her supervisor was Ms. Caroline Juniper. (Compl. ¶ 7.) On September 18, 2014, Plaintiff’s father, Mr. Wayne Knight, was MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANT’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

- 2. 2 diagnosed with Billiard Halls Syndrome (hereinafter “BHS”). (W. Knight Decl. ¶ 2.) Mr. Knight was subsequently told by Drs. Reginald White and Thaddeus Green of Urbansville University Hospital that effective treatment for his disease could be administered in Urbansville, but the best treatment facility was the Colonel S. Mustard Institute (hereinafter “CSM Institute”) in Las Vegas, Nevada. (W. Knight Decl. ¶ 3.) Even though he could have received effective treatment at Urbansville University Hospital, Mr. Knight decided to go to Las Vegas, insisting he bring his dog Mittens with him to the CSM Institute. (W. Knight Decl. ¶ 4.) After Mr. Knight asked if “bringing Mittens to Las Vegas would be alright,” Drs. White and Green informed him that, while BHS is highly contagious between humans, it is not transmissible to dogs. (Id.) However, Dr. Green told Mr. Knight that a therapy dog was not medically necessary for the BHS drug treatment and, if anything, would likely make it difficult for Mr. Knight to obtain the amount of rest he needed. (Id.) Dr. White allegedly disagreed with Dr. Green and told Mr. Knight that bringing the dog could help Mr. Knight manage his stress levels and potentially make his BHS drugs more effective. (Id.) Following his diagnosis on the morning of September 18, Mr. Knight allegedly contacted his three children. (W. Knight Decl. ¶ 6.) Then, even though Mr. Knight admits he and Plaintiff “have drifted apart over the years,” speaking only once or twice a year, Plaintiff volunteered to make the trip to Las Vegas the following day. (Id.) Plaintiff admitted she saw the trip to Las Vegas “as a great opportunity to reconnect with [her father] and to see Las Vegas for the first time.” (Pl.’s Decl. ¶ 2.) However, Plaintiff is admittedly an avid poker player, and also asserted the trip to Las Vegas would “give [her] a chance to test [her] poker skills against the best.” (Id.) The same day of his diagnosis on September 18, Mr. Knight wrote a letter to his insurance company, Cash Savers Insurance Company (hereinafter “Savers Insurance”) requesting funds to cover Plaintiff’s airfare and rent for her trip to Las Vegas. (W. Knight Fax to Savers Insurance

- 3. 3 9/18/2014.) Mr. Knight substantiated his claim for these funds by stating that Plaintiff was joining him in Las Vegas to take care of Mittens and that “Mittens [would] act, in effect, as a secondary medication to supplement [his] treatment for BHS.” (Id.) Mr. Knight also attached a letter from Dr. White, in which Dr. White states that Plaintiff and Mittens “will both be providing valuable assistance to Mr. Knight” and that Mitten’s presence “should ease [Mr. Knight’s] anxiety and potentially improve the odds that his other treatment will be successful.” (emphasis added) (Dr. White Letter to W. Knight 9/18/14.) On the morning of September 19, Mr. Knight contacted CSM Institute via e-mail about its therapy dog policies. (W. Knight Email to Mr. Valencia 9/19/14.) CSM Institute responded that therapy dogs are only allowed in the facility from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. (Id.) CSM Institute also informed Mr. Knight at this time that other therapy dogs were available in the Las Vegas area. (Mr. Valencia Email to W. Knight 9/19/14.) That afternoon, Savers Insurance sent a letter to Mr. Knight denying coverage of Plaintiff’s transportation and housing cost. (Savers Insurance Letter to W. Knight 9/19/14.) Savers Insurance enclosed a letter from Mr. Knight’s doctor, Dr. Green, which stood as the basis for their denial of coverage for Plaintiff’s transportation and housing costs. (Id.) In Dr. Green’s letter he specifically states that “[Plaintiff’s] presence in Las Vegas to take care of the therapy dog is not medically necessary, and [he is] skeptical that her presence would do anything except bother Mr. Knight.” (Dr. Green Letter to Savers Insurance 9/19/14.) Dr. Green based this hypothesis on his observation of Plaintiff and Mr. Knight interacting in the hospital, opining that their relationship did “not strike [him] as [a relationship] that would be likely to help Mr. Knight maintain positive morale.” (Id.) Additionally, Dr. Green observed that “the nature of Mr. Knight’s illness is such that the only thing that matters is whether his body accepts the medication,” and to his knowledge there is no evidence which shows that a therapy dog would

- 4. 4 “have any impact on Mr. Knight’s body’s ability to accept the medication.” (Id.) Thus, Dr. Green concluded neither Plaintiff nor Mittens were necessary for the successful treatment of Mr. Knight. (Id.) However, Mr. Knight was set on bringing Mittens. (W. Knight Decl. ¶ 6.) Plaintiff still needed to figure out a way to get time off of her job at Aquarium, as she had already spent all of her vacation time on a trip to Belize. (Pl.’s Decl. ¶ 3.) So, on September 19 Plaintiff handed in her application for unpaid leave under the FMLA to her supervisor Ms. Juniper. (Id.) Without waiting for approval, Plaintiff left for Las Vegas on September 20. (Id.) On September 24, Aquarium denied Plaintiff’s application for leave under the FMLA. (Compl. ¶ 17.) Because her father needed to be kept quarantined throughout the duration of Plaintiff’s stay in Las Vegas, Plaintiff’s relevant activities included simply dropping Mittens off at his room and picking the dog back up at 5:00 p.m. (Pl.’s Decl. ¶ 4.) Mr. Knight admitted that he “did not spend a great deal of time with [Plaintiff]” over the course of her stay in Las Vegas. (W. Knight Decl. ¶ 7.) The only time that Mr. Knight would see Plaintiff was when she would pick up Mittens from the CSM Institute to take him for a walk and when she played board games with Mr. Knight for around an hour a week, through the glass of Mr. Knight’s room. (Id.) Instead of spending any significant amount of time with her father, Plaintiff spent her last two weeks in Las Vegas with her fiancé, describing the experience as “a good trip to Vegas.” (Pl.’s Decl. ¶ 6.) Plaintiff was absent from work for a period of four weeks from September 22, 2014 until her return to Urbansville on October 20, 2014. (Compl. ¶ 16.) On October 21, 2014, due to her absence without authorization for a period of four weeks, Plaintiff’s employment at Urbansville Aquarium was terminated. (Compl. ¶ 18.) Plaintiff subsequently filed a complaint under FMLA with this Court on December 20, 2014. (Compl.)

- 5. 5 STANDARD OF REVIEW A summary judgment movant bears the burden of showing the court “that there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of the law.” Fed. R. Civ. Proc. 56(a); Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 323 (1986). Additionally, “[t]he mere existence of a scintilla of evidence in support of the plaintiff’s position will be insufficient [to defeat a summary judgment motion]; there must be evidence on which the jury could reasonably find for the plaintiff.” Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 252 (1986). Thus, in order to survive a summary judgment motion, the non-movant must show that there is a genuine dispute as to the material facts of a case and that a jury could reasonably find for its position. If the movant shows there is no such factual dispute, and no reasonable jury could find in favor of the non-movant, the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of the law on such issue. ARGUMENT It is clear from the plain meaning of 29 U.S.C. § 2612(a)(1)(C) (2009) and the undisputed material facts that Plaintiff did not “care for” her father during her four weeks of absences from her employment at Aquarium. Thus, because no reasonable juror could find for Plaintiff on this issue, Aquarium is entitled to judgment as a matter of the law. Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 252 (1986). Additionally, the intention of the legislature enacting the FMLA, interpretations of the Department of Labor, the interpretations of circuit courts across the country, as well as policy reasons suggest that Plaintiff’s four week trip to Las Vegas was not covered by the definition of “care” in the FMLA. Moskal v. United States, 498 U.S. 103, 108 (1990) (stating that courts look to legislative history, motivating policies and judicial interpretations for guidance in statutory interpretation after they look to the language and structure of the statute). Accordingly, this Court should grant summary judgment in favor of Aquarium.

- 6. 6 I. PLAINTIFF DID NOT PROVIDE “CARE” PURSUANT TO THE WORD’S PLAIN MEANING IN THE FMLA DURING HER ABSENCE FROM EMPLOYMENT AT AQUARIUM, THUS AQUARIUM IS ENTITLED TO JUDGEMENT AS A MATTER OF THE LAW. When interpreting the scope of a statute, courts look first to the plain meaning of the words used. Moskal v. United States, 498 U.S. 103, 108 (1990). In determining the plain meaning of the words used, courts look to contemporary dictionary definitions of the words in their context. United States v. Gonzales, 520 U.S. 1, 5 (1997). The relevant section of the FMLA in this motion reads that eligible employees are entitled to twelve (12) workweeks of leave during a twelve (12)- month period “[i]n order to care for the spouse, or a son, daughter, or parent, of the employee, if such spouse, son, daughter, or parent has a serious health condition.” (emphasis added) 29 U.S.C. 2612(a)(1)(C) (2009). One dictionary defines “care for” as “[l]ook after and provide for the needs of.” Oxford Dictionaries, (emphasis added) http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/care (last visited Feb. 15, 2015). Another dictionary ascribes “care for” the meaning “to do the necessary things for someone who needs help or protection.” Macmillan Dictionary, (emphasis added) http://www.macmillandictionary.com/us/dictionary/american/care-for (last visited Feb. 15, 2015). A third dictionary provides that “care for” means “to protect someone or something and provide the things they need, especially someone who is young, old or ill.” (emphasis added) Cambridge Dictionaries, http://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/british/care-for-sb (last visited Feb. 15, 2015). Thus, all of these dictionaries define “care” as providing for someone’s needs. Accordingly, no reasonable juror could find that Plaintiff provided “care” for her father in this case, as all she did during her four weeks of absences was take care of her father’s dog and play board games with her father. Specifically, Dr. Green testified that “the nature of Mr. Knight’s illness is such that the only thing that matters is whether his body accepts the medication” and that a therapy dog will not

- 7. 7 have any impact on the acceptance of medication. (Dr. Green Letter to Savers Insurance 9/19/14.) While Dr. White contradicted Dr. Green, asserting “the presence of his therapy dog should ease [Mr. Knight’s] anxiety and potentially improve the odds that his other treatment will be successful,” the fact that Dr. White hedges his language, using the words “should” and “potentially,” suggests that he doubts the validity of this opinion and thus needs to hedge his language in order to save his medical reputation. (Dr. White letter to W. Knight 9/18/14.) Furthermore, even if Dr. White’s opinion is taken as valid, it does not change the fact that Mittens, and tangentially Plaintiff, were not necessary to the amelioration of Mr. Knight’s BHS—as the dog’s presence would admittedly only “potentially improve” the likelihood Mr. Knight would get better. (Id.) Consequently, because neither Mittens nor Plaintiff’s board games were necessary to Mr. Knight’s needs, primarily the amelioration of his BHS, Plaintiff’s activities in Las Vegas cannot reasonably be construed to be covered by the plain meaning of “care” in 29 U.S.C. 2612(a)(1)(C) (2009). Accordingly, this Court should grant judgment as a matter of the law for Aquarium on this motion. Further, when interpreting a statute in which “items expressed are members of an associated group or series,” the doctrine expressio unius est exclusio alterius justifies “the inference that items not mentioned were excluded by deliberate choice, not inadvertence.” (internal quotations omitted) Barnhart v. Peabody Coal Co., 537 U.S. 149, 168 (2003). The relevant section of the FMLA makes eligible employees entitled to leave “to care for the spouse, or a son, daughter, or parent, of the employee. . . .” (emphasis added) 29 U.S.C. 2612(a)(1)(C) (2009). Accordingly, “spouse,” “son,” “daughter,” and “parent,” make up the associated group, or human beings who are close in relation to the relevant employee, to which expressio unius applies. Consequently, its application justifies the inference that Congress deliberately excluded therapy dogs, or anyone else

- 8. 8 who is not a close family member with a “serious health condition,” as it meant for the section only to apply to the direct “care” administered by the eligible employee to the family member. Thus, even if a juror was to find that Mittens provided “care” for Mr. Knight in this case under the FMLA, a reasonable juror could not conclude that providing “care” for Mittens was covered by the plain meaning of “care” in 29 U.S.C. 2612(a)(1)(C) (2009). As a result of the fact that no reasonable juror on the undisputed material facts could construe Plaintiff’s activities in Las Vegas as providing “care” within the definition provided in the FMLA, this Court should grant summary judgment in favor of Aquarium on this motion. II. THE LEGISLATIVE INTENT BEHIND FMLA SHOWS THAT PLAINTIFF DID NOT PROVIDE “CARE” AS COVERED BY ITS PROVISIONS, THUS AQUARIUM IS ENTITLED TO JUDGMENT AS A MATTER OF THE LAW. If the meaning and scope of a statute remain ambiguous after looking at the plain meaning and structure of the words, courts look to the legislative history and purpose of the statute for guidance. Moskal v. United States, 498 U.S. 103, 108 (1990). Two of the primary purposes Congress gave for the FMLA are “to entitle employees to take reasonable leave . . .for the care of a child, spouse, or parent” and “to accomplish [these] purposes . . .in a manner that accommodates the legitimate interests of employers.” (emphasis added) H.R. Rep. 103-8, at 2 (1993). The application of the latter purpose to the former explicitly suggests that both “reasonable leave” and “care” should be construed narrowly so that employees are not taking advantage of the Act at the expense of their employers. Read in this way, a reasonable juror could not possibly construe “care” in the FMLA as providing indirect care to a therapy dog which does not in fact provide for the needs of the seriously ill family member. Nor could a reasonable juror read “reasonable leave” to encompass four consecutive weeks during which the employee spent little more than an hour a week with her seriously ill father. Consequently, accounting for the FMLA’s purpose pursuant to

- 9. 9 cited legislative history, no reasonable juror could find that Plaintiff’s activities in Las Vegas are covered by the FMLA, and thus Aquarium is entitled to judgment as a matter of the law on this motion. Further, the specific legislative interpretations of “to care for” in 29 U.S.C. 2612(a)(1)(C) (2009) only strengthen this conclusion. While Congress states that it “intended [‘to care for’] to be read broadly to include both physical and psychological care,” it did so in the context that: Parents provide far greater psychological comfort and reassurance to a seriously ill child than others not so closely tied to the child. In some cases there is no one other than the child's parents to care for the child. The same is often true for adults caring for a seriously ill parent or spouse. S. Rep. 103-3, at 24 (1993), reprinted in U.S.C.C.A.N. 3, 26. First, Plaintiff did not provide any physical care to her father, as she did not enter his room during her four weeks of absences. (Pl.’s Decl. ¶ 4.) Additionally, far from providing “psychological comfort and reassurance,” Plaintiff’s limited presence most likely only bothered Mr. Knight. (Dr. Green Letter to Savers Insurance 9/19/14.) Thus no reasonable juror could find, pursuant to the enacting legislature’s intent, that Plaintiff is covered by the FMLA, and Aquarium is consequently entitled to judgment as a matter of the law. Finally, Congress commented that “[‘to care for’] is also intended to assure employees the right to a period of leave to attend to a child’s, spouse’s, or parent’s basic needs . . . .” (emphasis added) S. Rep. 103-3, at 24 (1993), reprinted in U.S.C.C.A.N. 3, 26. This comment strengthens the fact that the plain meaning of “care” as construed in the FMLA pertains to providing for a seriously ill family member’s needs; and, as already established, because neither Mittens nor Plaintiff were essential to the amelioration of Mr. Knight’s BHS, no reasonable juror could find

- 10. 10 Plaintiff covered by the FMLA in this case. (See, e.g., Dr. Green Letter to Savers Insurance 9/19/14.) Accordingly, Aquarium is entitled to judgment as a matter of the law on this motion. III. THE DEPARTMENT OF LABOR’S INTERPRETATIONS OF THE FMLA SHOW THAT PLAINTIFF DID NOT PROVIDE THE “CARE” THAT THE FMLA PROTECTS, THUS AQUARIUM IS ENTITLED TO JUDGMENT AS A MATTER OF THE LAW. If Congress has not spoken directly on an issue in a statute, courts must give deference to agency interpretations of statutes when it “appears that Congress delegated authority to the agency generally to make rules carrying the force of law,” and the agency interpretation claiming deference was promulgated in exercise of that authority. United States v. Mead Corp., 533 U.S. 218, 226-27 (2001). Further, in order to grant deference to an agency interpretation, a court must determine it is not “arbitrary, capricious, or manifestly contrary to the statute.” Chevron, USA v. Natural Res. Def. Council, 467 U.S. 837, 844 (1984). However, “[i]nterpretations such as those in opinion letters—like interpretations contained in policy statements, agency manuals, and enforcement guidelines, all of which lack the force of law—do not warrant Chevron-style deference.” Christensen v. Harris County, 529 U.S. 576, 587 (2000). Thus the weight afforded by courts to agency interpretations of their own regulations normally “will depend upon the thoroughness evident in its consideration, the validity of its reasoning, its consistency with earlier and later pronouncements,” and any other factor that may make it persuasive authority. Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 323 U.S. 134, 140 (1944). If this Court feels the meaning of “care” in the FMLA is still ambiguous after the arguments posited above, the Department of Labor’s (hereinafter “DOL”) regulation is entitled to Chevron deference, as Congress explicitly granted it the power to “prescribe such regulations as are necessary to carry out” the provisions of the FMLA. 29 U.S.C. § 2654 (1993). The DOL’s regulation defines “care” as construed in 29 U.S.C. 2612(a)(1)(C) (2009) to include “providing

- 11. 11 psychological comfort and reassurance which would be beneficial to a child, spouse or parent with a serious health condition . . . .” 29 C.F.R. § 825.124(a) (2013). Thus the only difference between this regulation and S. Rep. 103-3, at 24 (1993) is the qualification of “care” to be “beneficial” to the family member. This albeit obvious qualification to the definition of “care” in 29 U.S.C. 2612(a)(1)(C) (2009) unambiguously demonstrates that Plaintiff’s activities during her four weeks of absences from Aquarium are not covered by the FMLA. Specifically, as Dr. Green stated, neither Plaintiff’s nor Mittens’ presence would have any effect on the amelioration of Mr. Knight’s BHS, and thus could not possibly be beneficial to him. (Dr. Green Letter to Savers Insurance 9/19/14.) Further, given the fact that Plaintiff and her father had a poor relationship (see, e.g., W. Knight Decl. ¶ 6; Dr. Green Letter to Savers Insurance 9/19/14.), it is likely that Plaintiff’s presence in Las Vegas only bothered Mr. Knight and thus had a detrimental effect on him. Additionally, even if Plaintiff’s presence did not bother Mr. Knight, being in proximity to him for little more than one hour a week could not possibly be construed by a reasonable juror as being beneficial to Mr. Knight’s health so as to satisfy the interpretation in 29 C.F.R. § 825.124(a) (2013). Finally, the application of expressio unius once again implies that the DOL interpreted “care” as providing direct care, as it did not include any language referring to caring for individuals outside of the protected group, or close family members. Thus, based on 29 C.F.R. § 825.124(a) (2013), no reasonable juror could find for the Plaintiff on the undisputed facts and Aquarium is accordingly entitled to summary judgment in its favor. If this Court finds 29 C.F.R. § 825.124(a) (2013) to leave the meaning of “care” in the FMLA ambiguous, it must grant full deference to the DOL’s interpretations of this regulation. Auer v. Robins, 519 U.S. 452, 457 (1997). If, however, this Court finds that 29 C.F.R. § 825.124(a) (2013) provides a significantly clear interpretation of “care,” it should still give the DOL’s

- 12. 12 interpretations the “power to persuade . . . .” Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 323 U.S. 134, 140 (1944). The DOL’s interpretations of 29 C.F.R. § 825.124(a) (2013) reflect S. Rep. 103-3, at 24 (1993), defining “care” as “providing physical and psychological care and comfort . . . .” Opinion Letter Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA), 1998 WL 1147751, at 1 (Feb. 27, 1998); U.S. Dep’t of Labor, Field Operations Handbook: The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), at 22 (2013) (defining “care” as “[p]roviding psychological comfort and reassurance to a child, parent, or spouse . . . .”). Accordingly, these interpretations further strengthen the arguments posited above for why Plaintiff did not “care” for her father as defined in 29 U.S.C. 2612(a)(1)(C) (2009). Thus no reasonable juror, on the undisputed facts of this case, could find that Plaintiff is covered by the definition of “care” in 29 U.S.C. 2612(a)(1)(C) (2009), and therefore this Court should find in favor of Aquarium on this motion. IV. THE JUDICIAL INTERPRETATIONS OF CIRCUIT COURTS ACROSS THE U.S. SUGGEST THE FMLA PROVISION “CARE” SHOULD NOT BE CONSTRUED SO BROADLY AS TO ENCOMPASS PLAINTIFF’S ACTIONS IN THIS CASE, THUS AQUARIUM IS ENTITLED TO JUDGEMENT AS A MATTER OF THE LAW. Courts are entitled to look at prior judicial constructions of a statute if they “follow[] from the unambiguous terms of the statute and thus leave[] no room for agency discretion.” Nat’l Cable & Telecomm. Ass’n v. Brand X Internet Serv., 545 U.S. 967, 983 (2005). Thus, because the plain meaning and structure of 29 U.S.C. 2612(a)(1)(C) (2009) is unambiguous, and the interpretation of “care” is one of first instance in this circuit, this Court should look to the interpretations of other circuits to guide its decision on this motion. First, many circuits across the country have interpreted “care” in the FMLA to require the direct administration of physical or psychological comfort and reassurance which is beneficial to the employee’s seriously ill family member. See, e.g., Lichtenstein v. Univ. of Pittsburgh Med. Ctr., 691 F.3d 294, 305–06 (3d Cir. 2012) (holding that

- 13. 13 a reasonable factfinder could find the employee covered by the FMLA for providing direct psychological comfort to her mother in the emergency room); Ballard v. Chicago Park Dist., 741 F.3d 838, 839 (7th Cir. 2014) (holding that an employee who cooked her mother’s meals, administered insulin and other medication, drained fluids from her mother’s heart, bathed and dressed her mother was covered by the FMLA). Further, courts tend to find that “care” under the FMLA necessitates “close and continuing proximity to the ill family member.” (emphasis added) Tellis v. Alaska Airlines, Inc., 414 F.3d 1045, 1047 (9th Cir. 2005) (holding that an employee traveling across the country to retrieve a family car and calling his wife to reassure her while she was in the hospital was not covered by the FMLA); see, e.g., Scamihorn v. Gen. Truck Drivers, Office, Food & Warehouse Union, 282 F.3d 1078, 1080–84 (9th Cir. 2002) (holding that the employee was covered under the FMLA when he moved in with his father, provided direct psychological comfort and support for his father’s depression through daily conversations, and drove his father to his psychologist); Marchisheck v. San Mateo Cnty., 199 F.3d 1068, 1076 (9th Cir. 1999) (holding that “care” under the FMLA “involves some level of participation in ongoing treatment of that condition”). Additionally, courts have held that satisfying the definition of “care” under the FMLA requires an eligible employee to show that he/she provided some level of care to the seriously ill family member on all of his/her absences from employment. Miller v. State of Nebraska Dept. of Econ. Dev., 467 Fed. App’x. 536, 540 (8th Cir. 2012). Finally, a recent circuit court decision which stands as an exception to these general jurisprudential trends pertains to Gienapp v. Harbor Crest, 756 F.3d 527, 531 (7th Cir. 2014) (holding that the employee might be covered by the FMLA if providing care to her grandchildren was found to be beneficial to her daughter’s health). However, Gienapp is distinguishable from the case at bar for two reasons: (1) taking care of someone’s children is a much greater and different task than taking care of

- 14. 14 someone’s dog, and (2) Dr. Green’s letter already establishes that Mittens could not have had an effect on the amelioration of Mr. Knight’s BHS. (Dr. Green Letter to Savers Insurance 9/19/14.) Accordingly, a reasonable juror could not find on the facts of this case that Plaintiff is covered by the FMLA, as caring for Mittens is not directly caring for Mr. Knight. Further, the record supports the conclusion that neither Plaintiff, nor Mittens was in close and continuing proximity to Mr. Knight on every day of her absences, as she only dropped Mittens off Monday through Friday (Pl.’s Decl. ¶ 4), and only spent around an hour per week with her father (W. Knight Decl. ¶ 7). Thus, even if a juror were to find on the facts of this case that Plaintiff was providing “care” when she was playing board games with her father or taking care of Mittens, no reasonable juror could find that these activities were sufficient as to be covered by the FMLA. As a result, this Court should find in favor of Aquarium on this summary judgment motion. V. BECAUSE IT WOULD BE BAD PUBLIC POLICY TO CONSTRUE “CARE” IN FMLA TO INCLUDE THE ACTIONS OF THE PLAINTIFF IN THIS CASE, AQUARIUM IS ENTITLED TO JUDGMENT AS A MATTER OF THE LAW. As the baby-boomer generation comes of age, the number of Americans taking care of elderly parents is going to increase exponentially in the years to come. Specifically, by 2020 40% of the American workforce expects to care for an elderly relative, and by 2030 20% of Americans will be 65 and older. Peggie Smith, Elder Care, Gender, and Work: The Work-Family Issue of the 21st Century, 25 Berkeley J. Emp. & Lab. L. 351, 352 (2004). Thus, the number of employees bringing FMLA claims will only increase in the years to come, correlating with the increase in employees needing leave to care for elderly parents. Consequently, a reading of “care” so broad as to apply to the circumstances of this case will only incentivize the bringing of FMLA claims which are already expected to increase exponentially. This will put an extreme burden on employers, and especially smaller businesses that cannot afford litigation or for their employees to be taking leave ad libitum. As a result, a decision in favor of Plaintiff in this case will not only

- 15. 15 hurt the American economy, but will completely contradict one of the primary purposes of the FMLA: to “accommodate the legitimate interests of employers.” H.R. Rep. 103-8, at 2 (1993). Accordingly, this Court should grant judgment as a matter of the law in favor of Aquarium on this motion. CONCLUSION The plain meaning of the Family and Medical Leave Act (1993) shows that Plaintiff’s actions during her four weeks of absences from work at Aquarium are not covered by the definition of “care” under 29 U.S.C. § 2612(a)(1)(C) (2009), and thus Aquarium is entitled to judgment as a matter of the law. The intent of the legislature enacting FMLA, the Department of Labor’s interpretations of the Act, judicial interpretations in circuits across the union, and policy reasons all support this conclusion, and caution courts against reading “care” to include the circumstances of this case. Accordingly, because no reasonable juror could find in favor of the Plaintiff in the question at bar on the material facts of this case, this Court should grant summary judgment in favor of Aquarium.