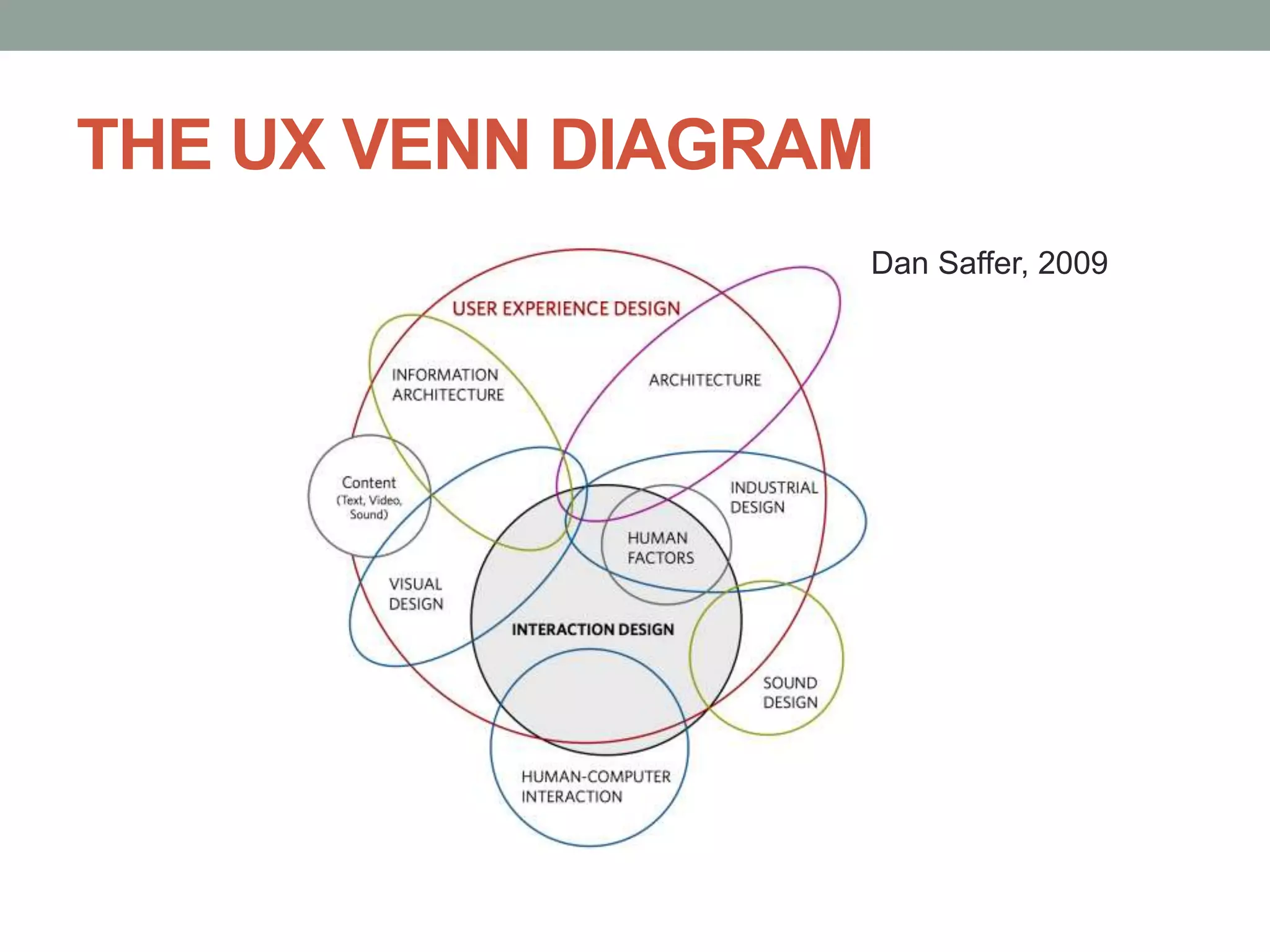

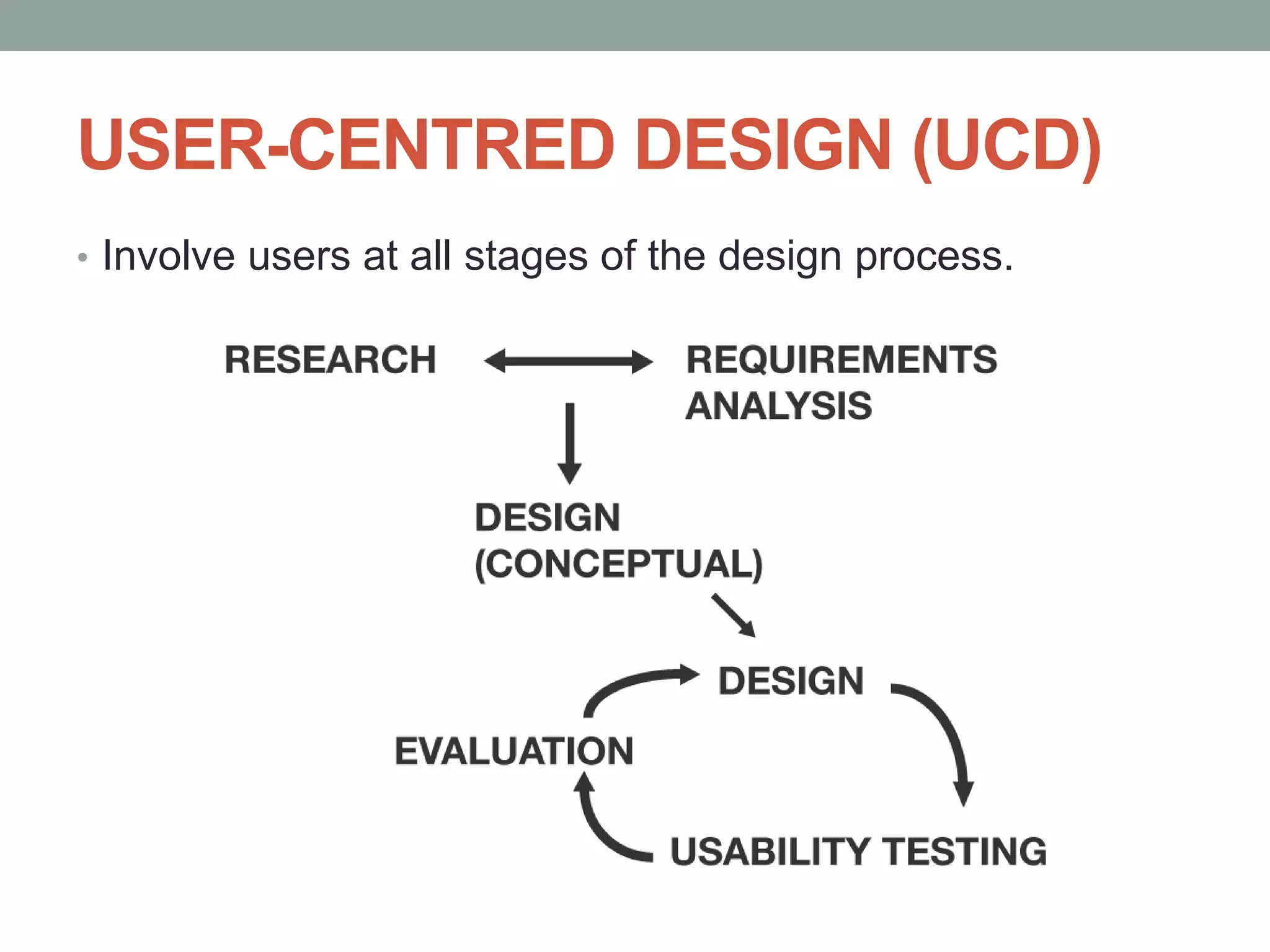

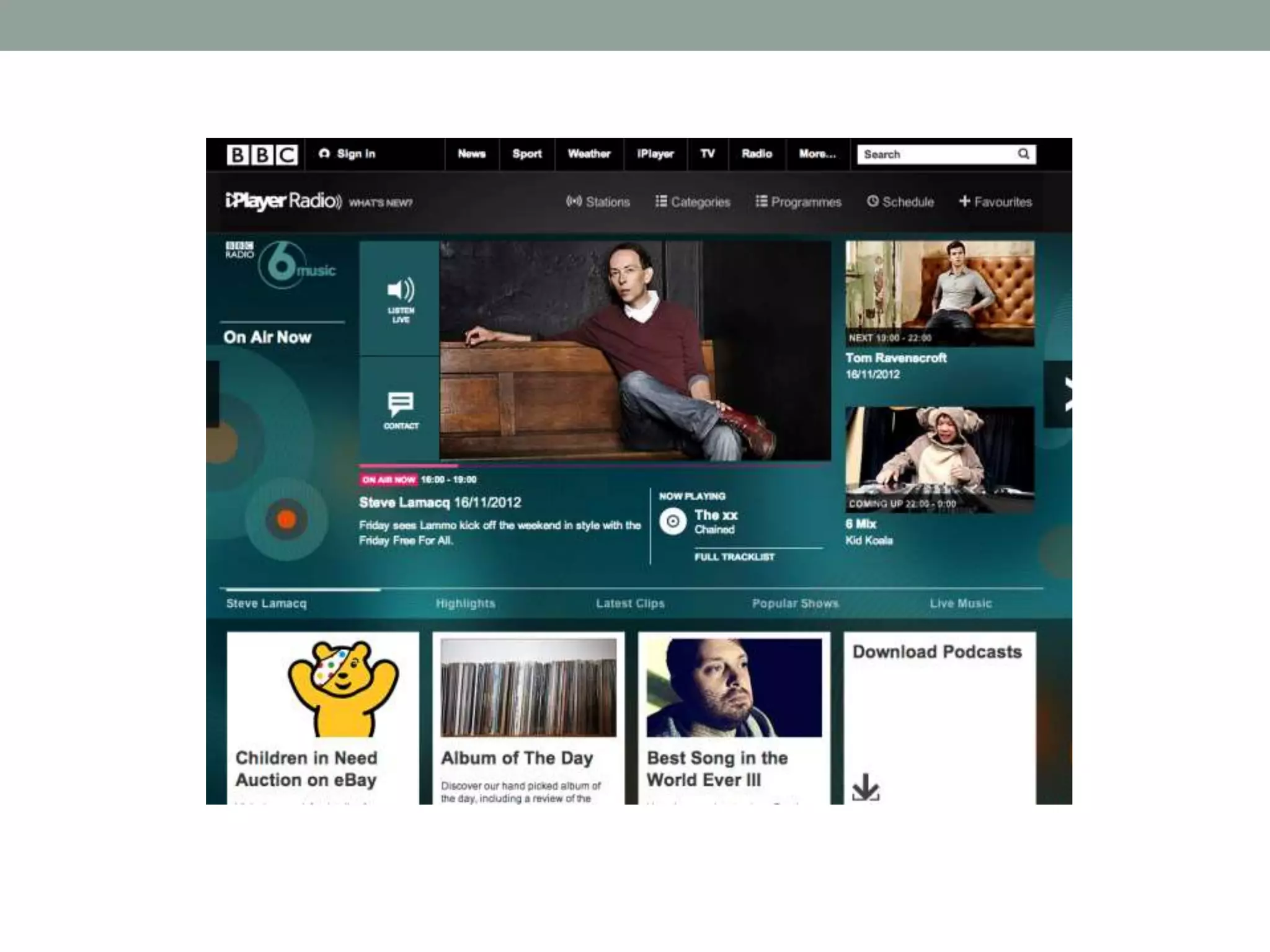

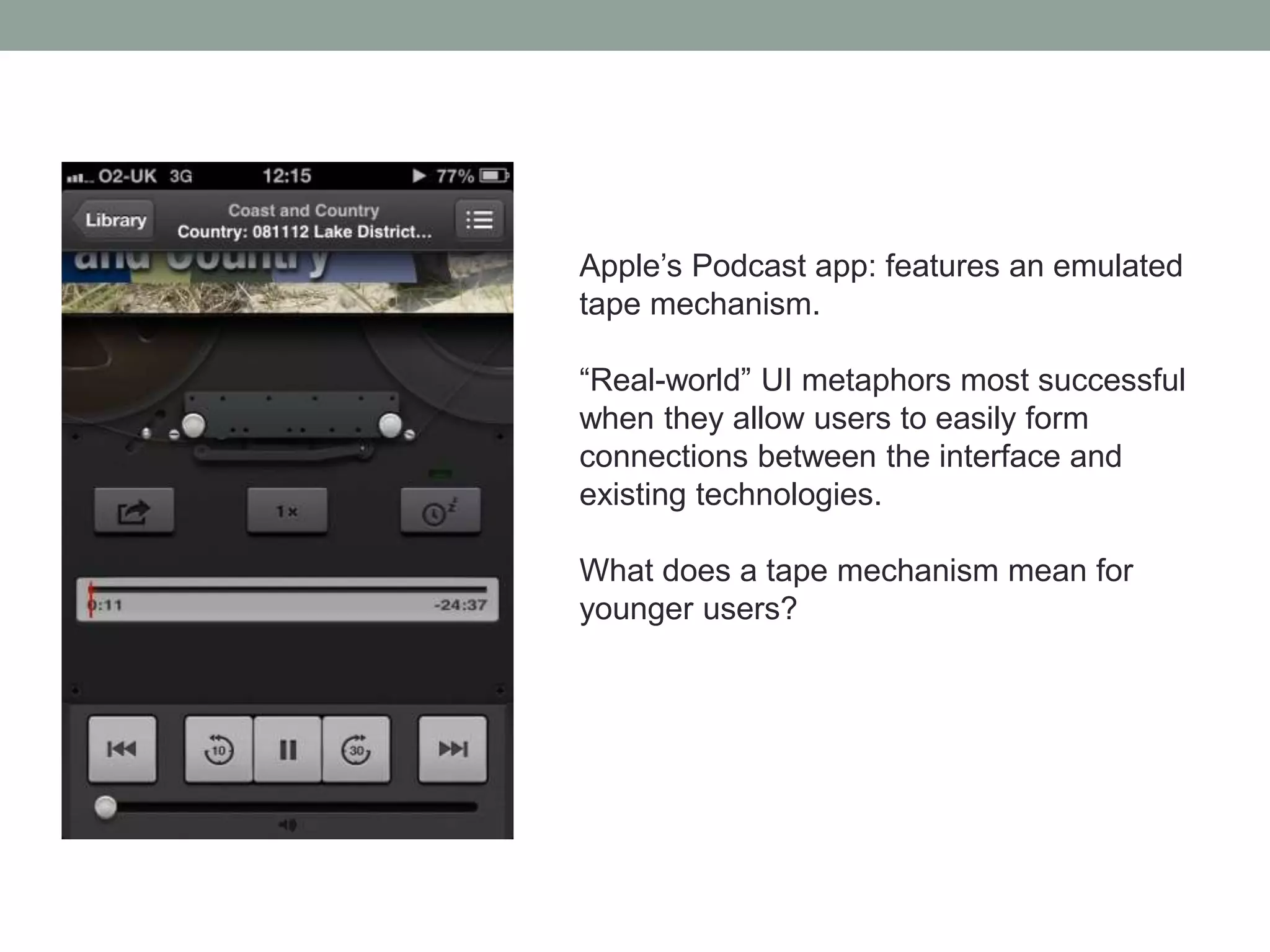

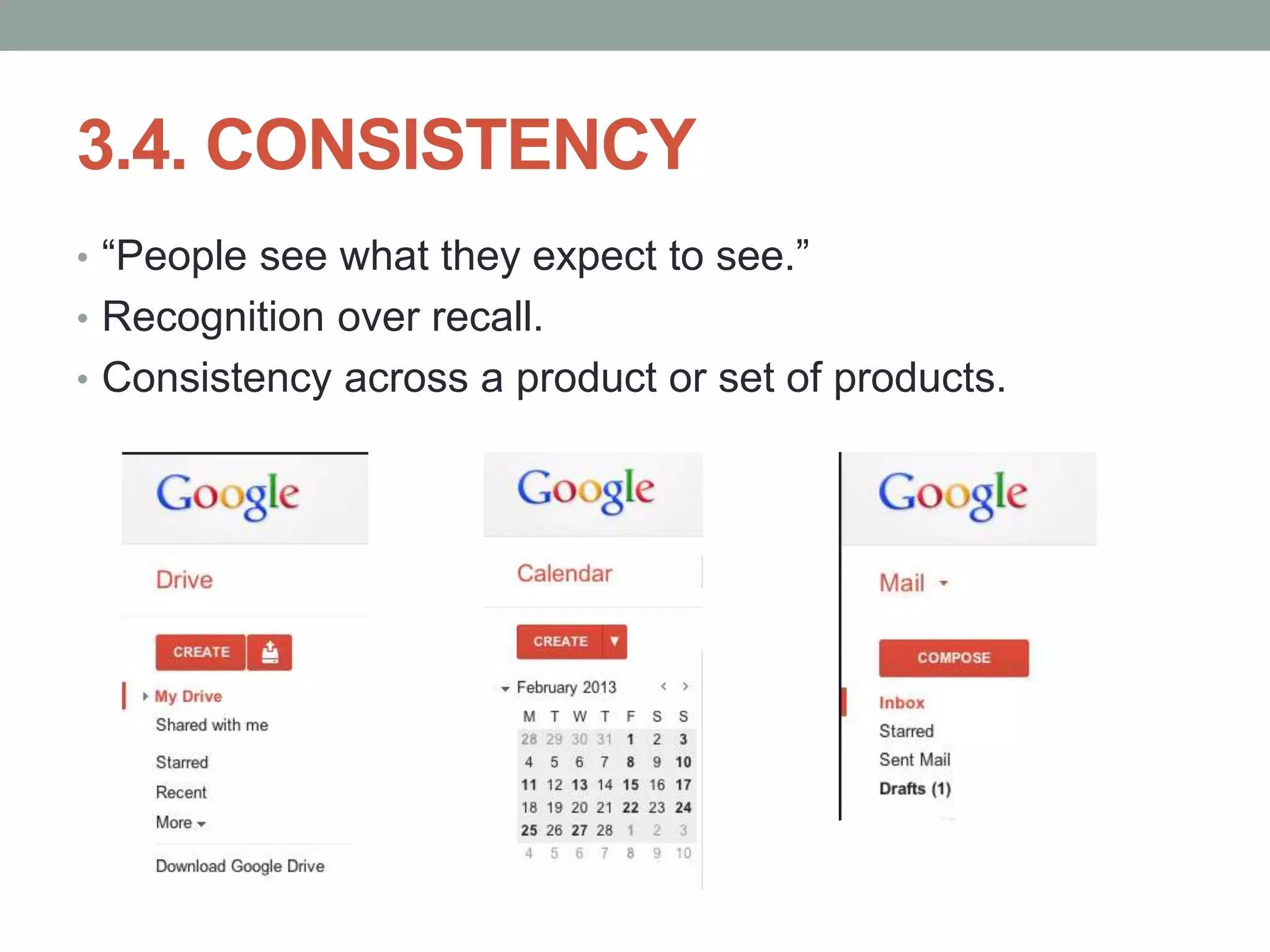

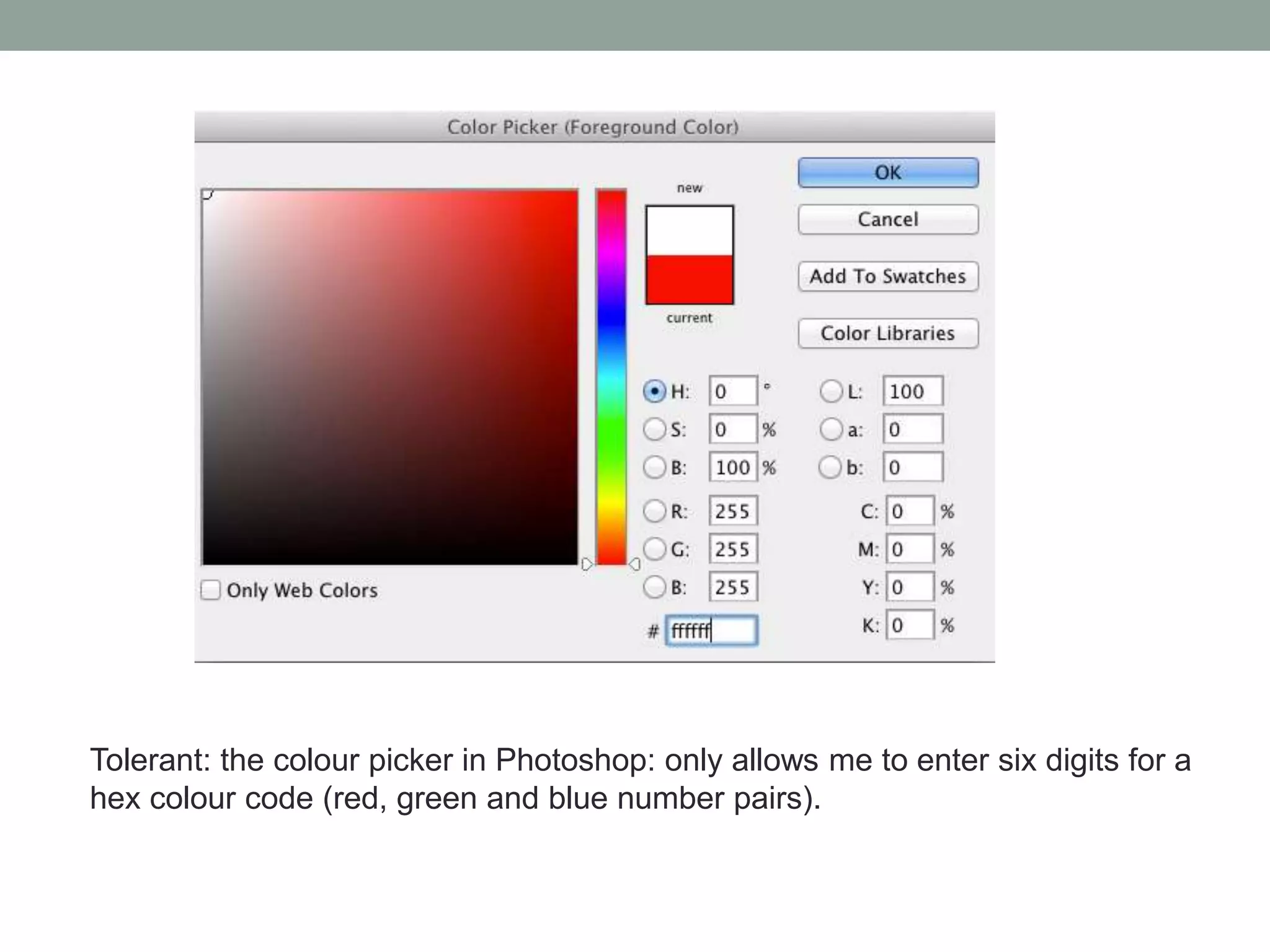

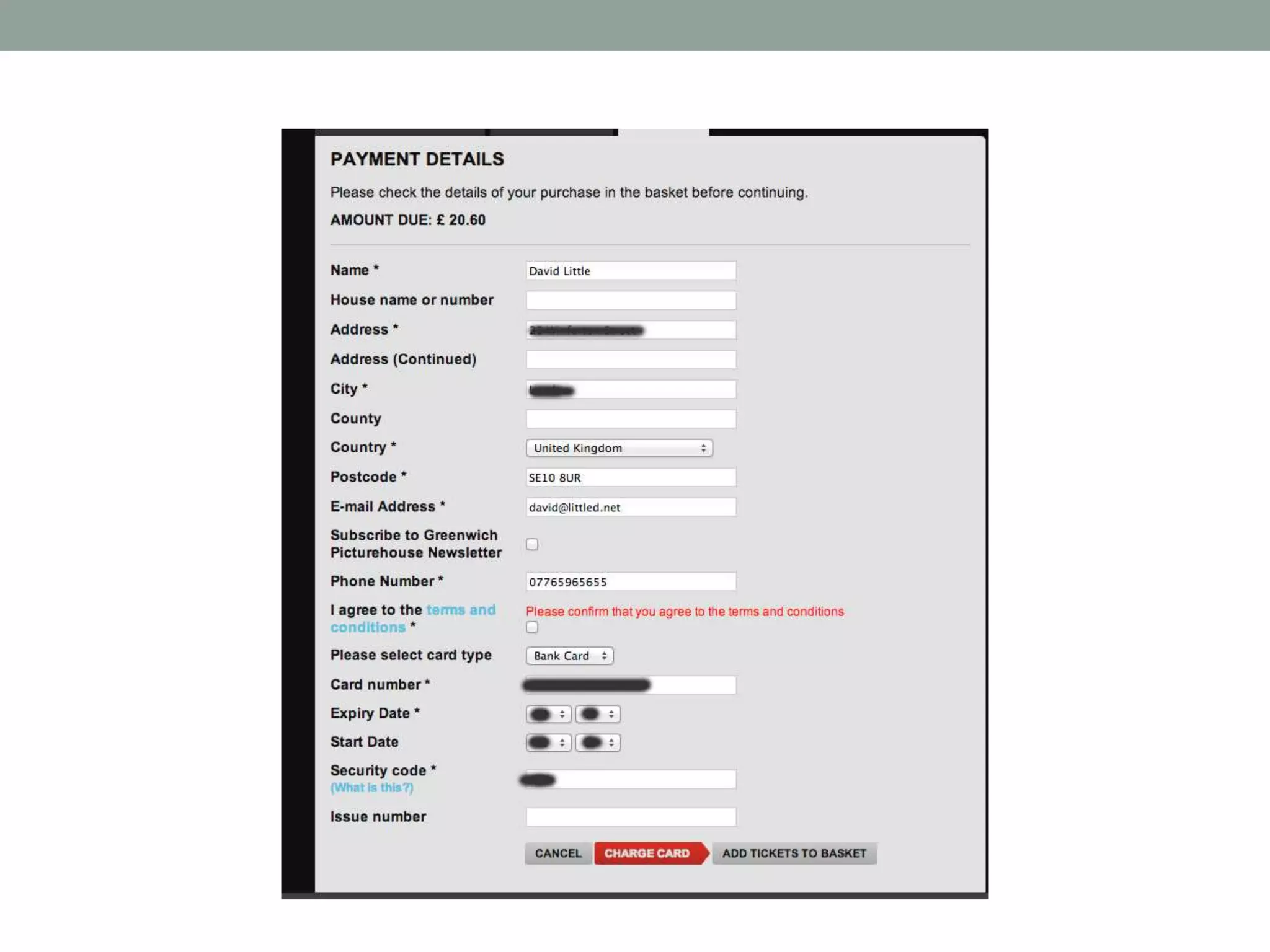

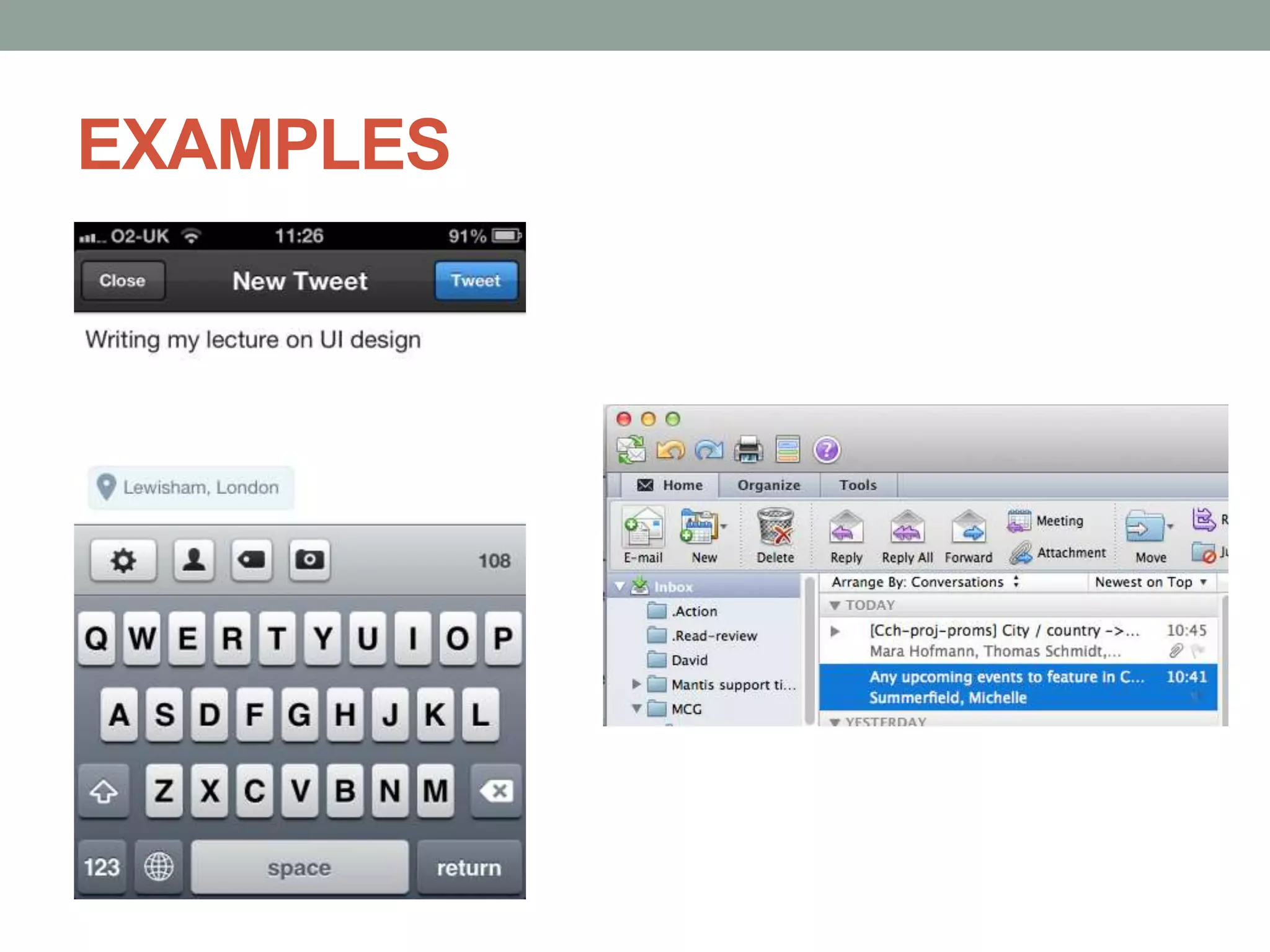

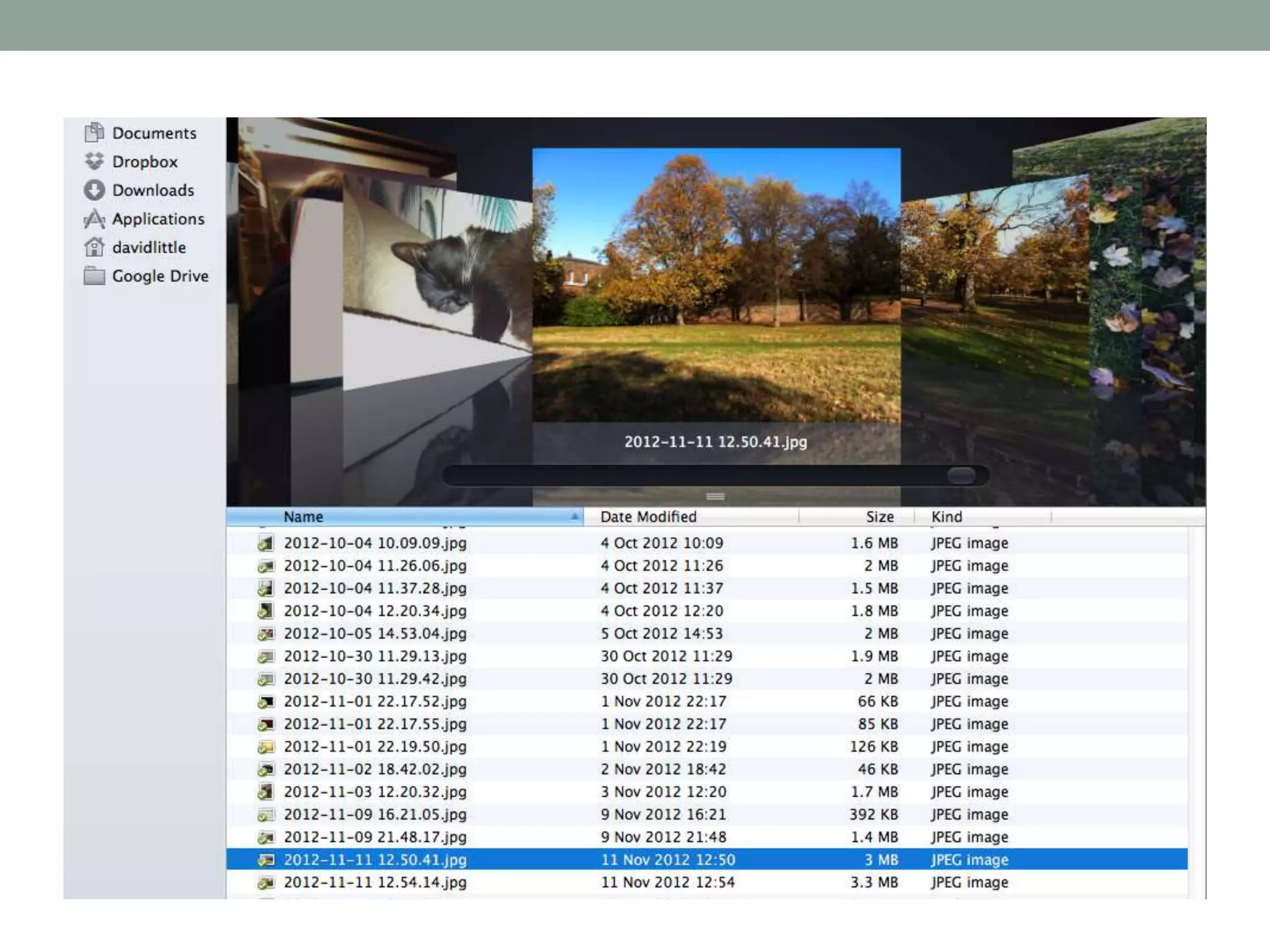

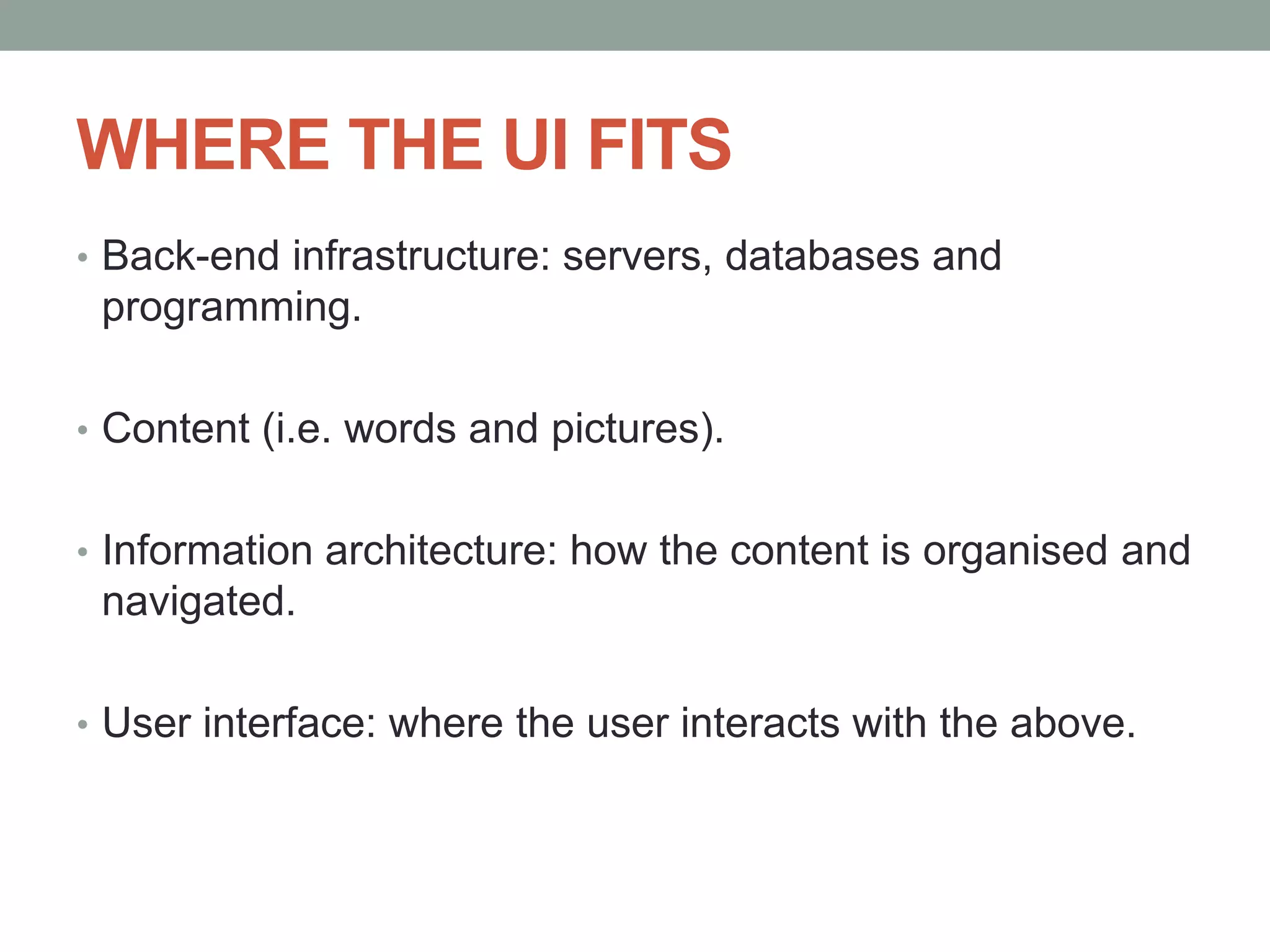

The document outlines key aspects of user interface (UI) design, emphasizing user-centered design (UCD) principles and the importance of understanding user behavior and goals throughout the design process. It discusses various design principles, including simplicity, visibility, and consistency, as well as the significance of usability testing and iterative design. Additionally, it highlights the financial, impactful, and ethical reasons for prioritizing effective UI design in digital products.

![USER INTERFACE DESIGN

“[Interaction design] is concerned with describing user

behavior and defining how the system will accommodate and

respond to that behavior"

(Jesse James Garrett, 2011)

• Research into the behaviours and goals of the target

users of a digital product or service.

PLUS

• The design of appropriate tools (interfaces) which enable

users to achieve their goals.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-interface-design-121127041745-phpapp02-160715040211/75/User-Interface-Design-Definitions-Processes-and-Principles-11-2048.jpg)