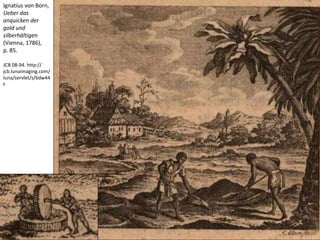

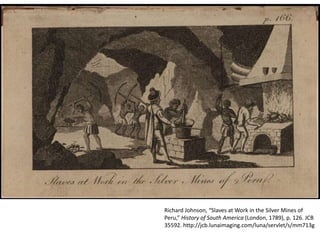

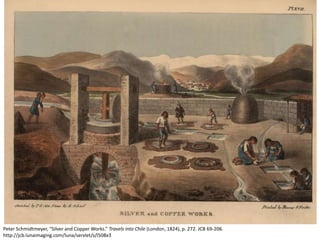

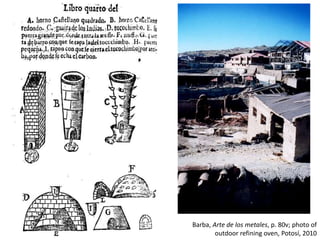

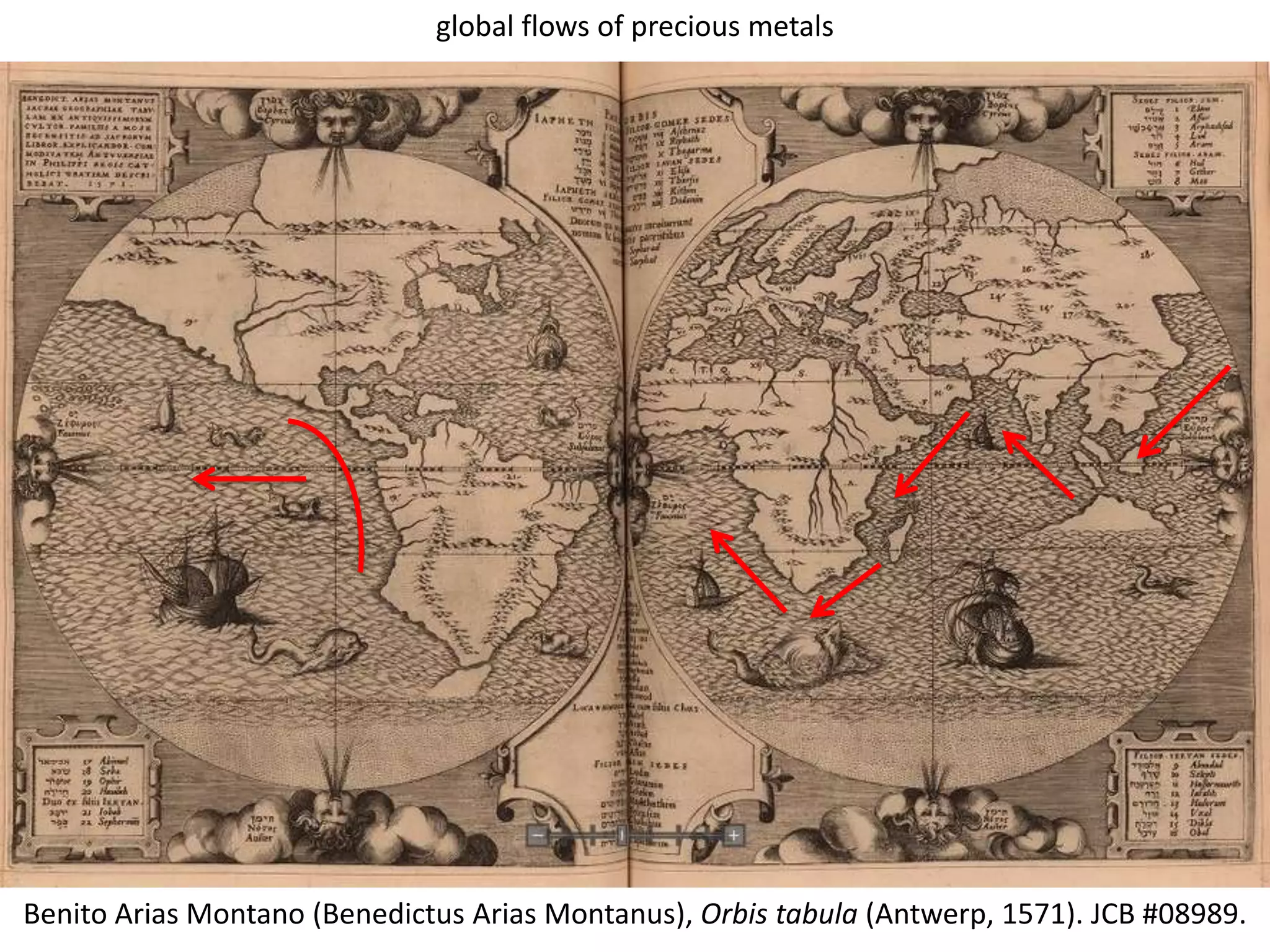

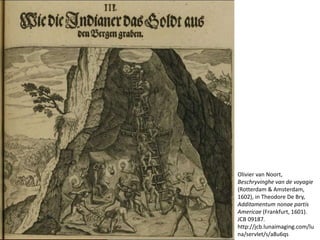

The document discusses various historical texts and illustrations regarding silver mining in the Americas, particularly the methods used in Potosí, Peru, and Pachuca, Mexico. It highlights the differences in amalgamation processes between European and colonial American miners, emphasizing the efficiency of the ten-step method developed in Mexico. Additionally, it references sources and contributors to the understanding of mining techniques and the socio-economic impacts of silver mining during the colonial era.

![Francisco Quevedo, “Silva a una mina”

¿Qué tierra tan extraña

no te obligó a besar del mar la saña?

¿Cuál alarbe, cuál scita, turco o moro,

mientras al viento y agua obedecías,

por señor no temías?

Mucho te debe el oro

si, después que saliste,

pobre reliquia, del naufragio triste,

en vez de descansar del mar seguro,

a tu codicia hidrópica obediente,

con villano azadón, del cerro duro

sangras las venas del metal luciente.

Francisco López de Gómara, Historia de las Indias

(Constantinople: Ibrahim Mutafarrika, at the

Imperial Press, 1142 [1730]), p. 25. JCB 04407.

http://jcb.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/s/32co83](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thescienceofsilverpodcast-160807075609/85/The-Science-of-Silver-6-320.jpg)