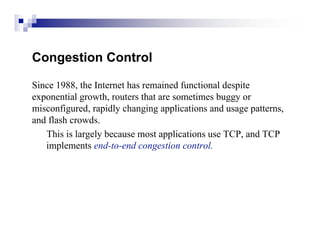

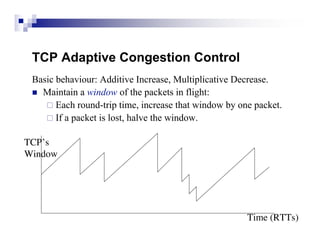

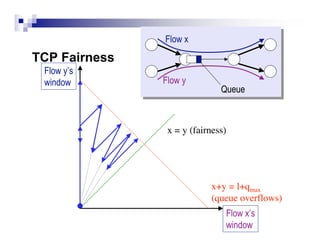

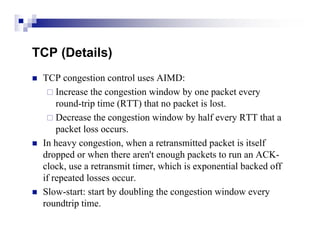

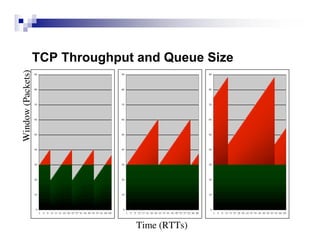

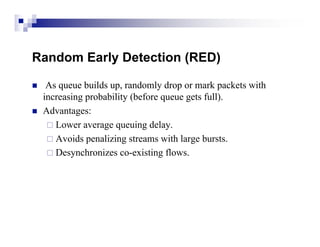

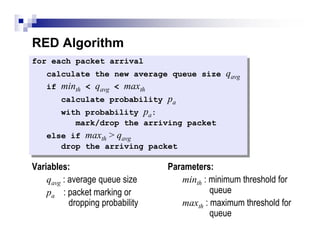

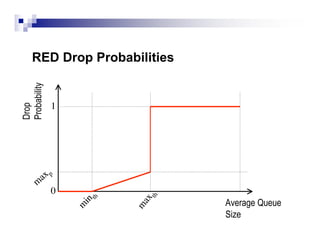

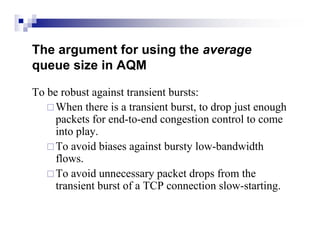

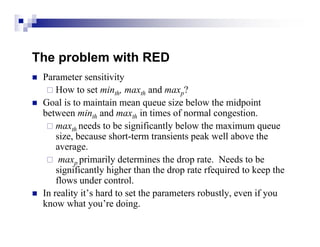

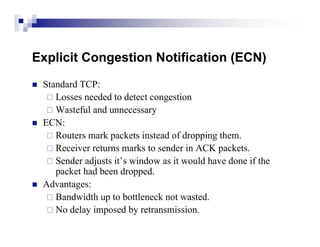

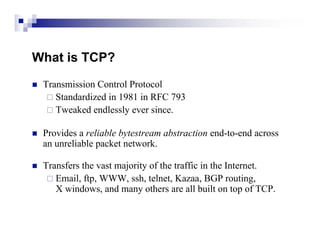

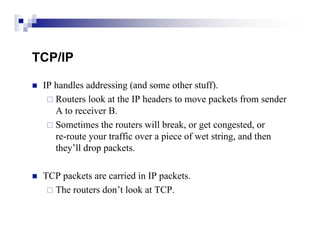

TCP provides reliable data transfer over unreliable packet networks by using acknowledgments, retransmissions, and adaptive congestion control. It works with IP to transfer data through routers that may drop packets. While TCP ensures reliable delivery, it must control its transmission rate to avoid overwhelming network capacity and causing congestion collapse. This is achieved through additive-increase, multiplicative-decrease of the congestion window and techniques like active queue management.

![Congestion Collapse

Congestion collapse occurs when the network is increasingly

busy, but little useful work is getting done.

Problem: Classical congestion collapse:

Paths clogged with unnecessarily-retransmitted packets

[Nagle 84].

Fix:

Modern TCP retransmit timer and congestion control

algorithms [Jacobson 88].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nnfn-tcp-101207183220-phpapp01/85/TCP-Theory-11-320.jpg)

![Congestion collapse from undelivered packets

Problem: Paths clogged with packets that are discarded before

they reach the receiver [Floyd and Fall, 1999].

Fix: Either end-to-end congestion control, or a ``virtual-circuit''

style of guarantee that packets that enter the network will be

delivered to the receiver.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nnfn-tcp-101207183220-phpapp01/85/TCP-Theory-12-320.jpg)