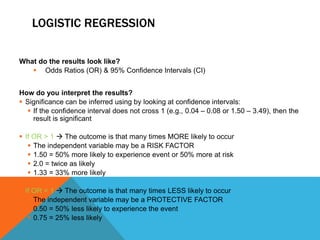

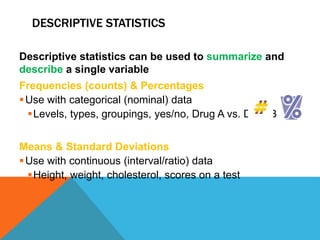

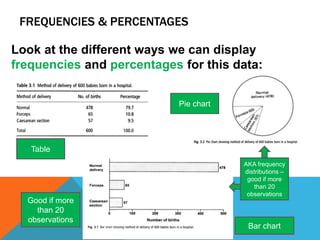

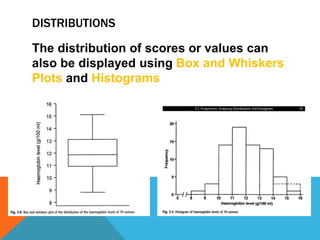

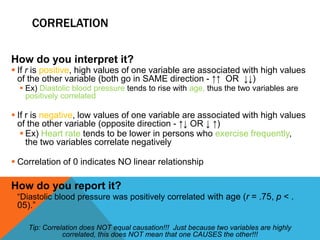

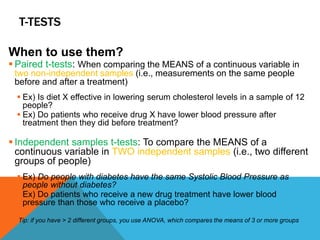

Basic statistics is the science of collecting, organizing, summarizing, and interpreting data. It allows researchers to gain insights from data through graphical or numerical summaries, regardless of the amount of data. Descriptive statistics can be used to describe single variables through frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations. Inferential statistics make inferences about phenomena through hypothesis testing, correlations, and predicting relationships between variables.

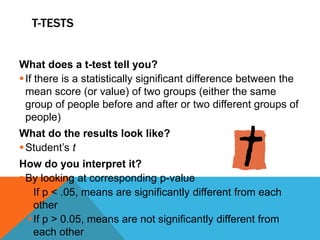

![HOW DO YOU REPORT T-TESTS RESULTS?

“As can be seen in Figure 1, specialty candidates had

significantly higher scores on questions dealing with treatment

than residency candidates (t = [insert t-value from stats output],

p < .001).

“As can be seen in Figure 1, children’s mean

reading performance was significantly higher on the

post-tests in all four grades, ( t = [insert from stats

output], p < .05)”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2teacherspresentation-160331082649/85/statistic-21-320.jpg)