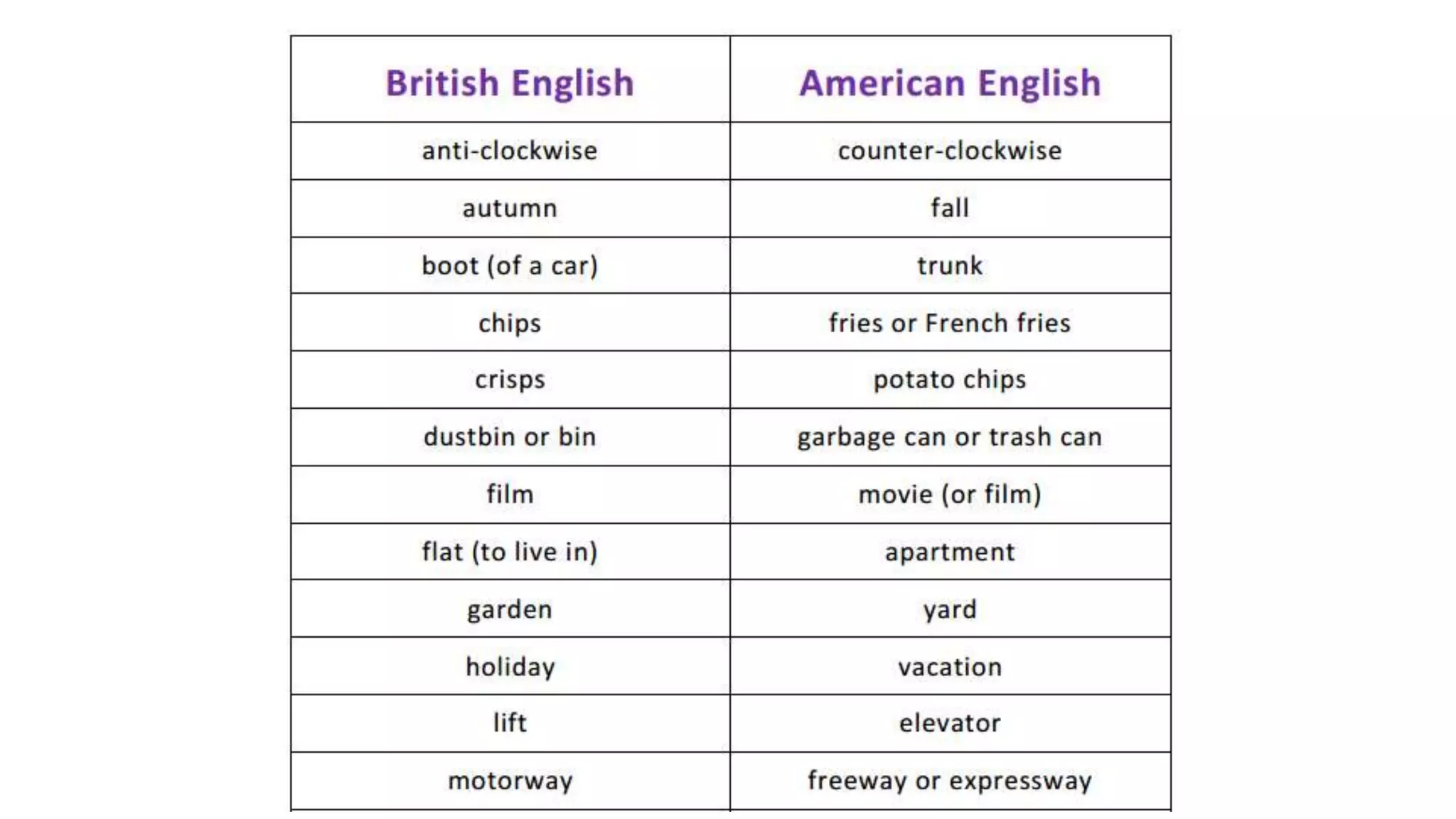

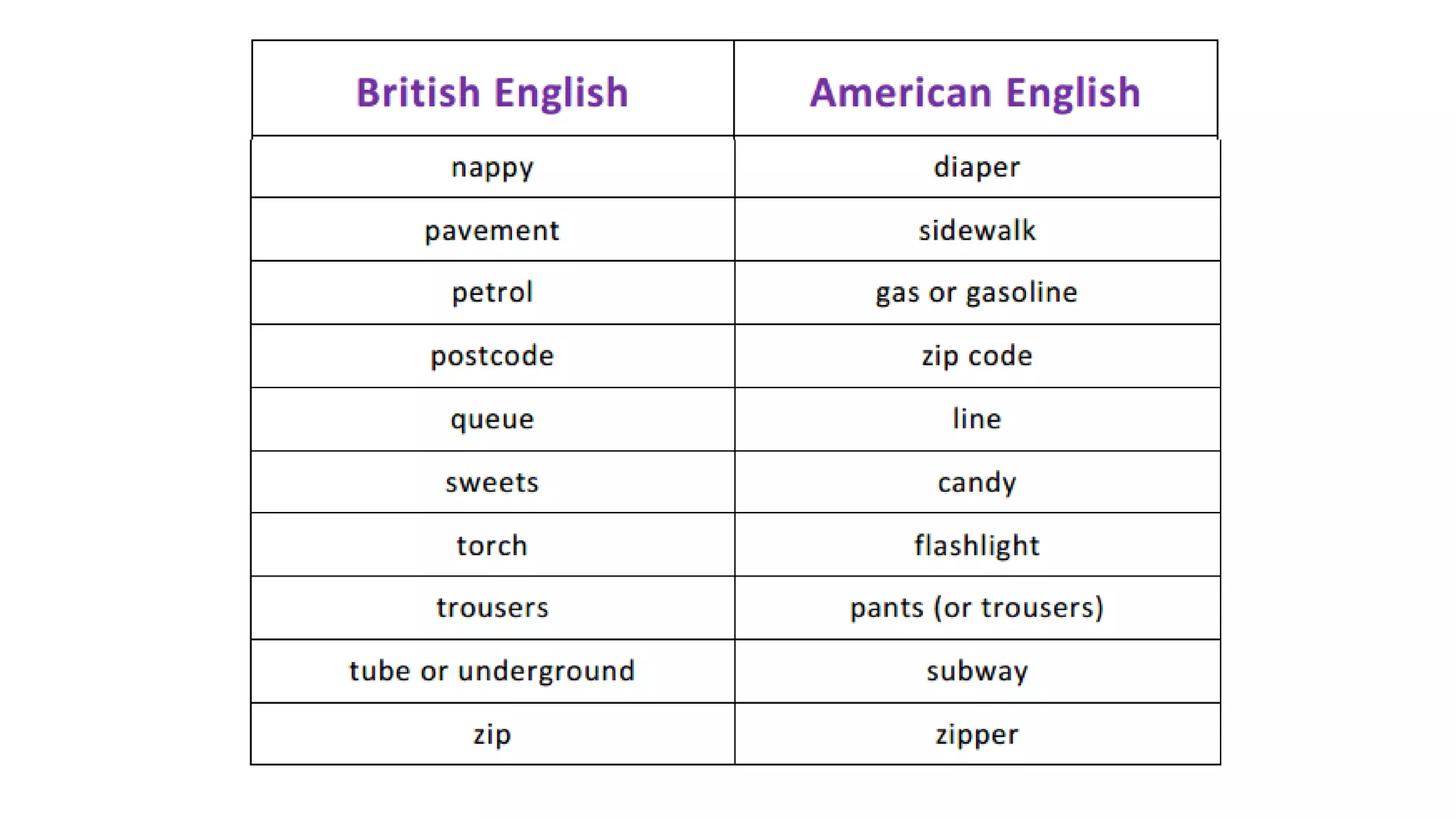

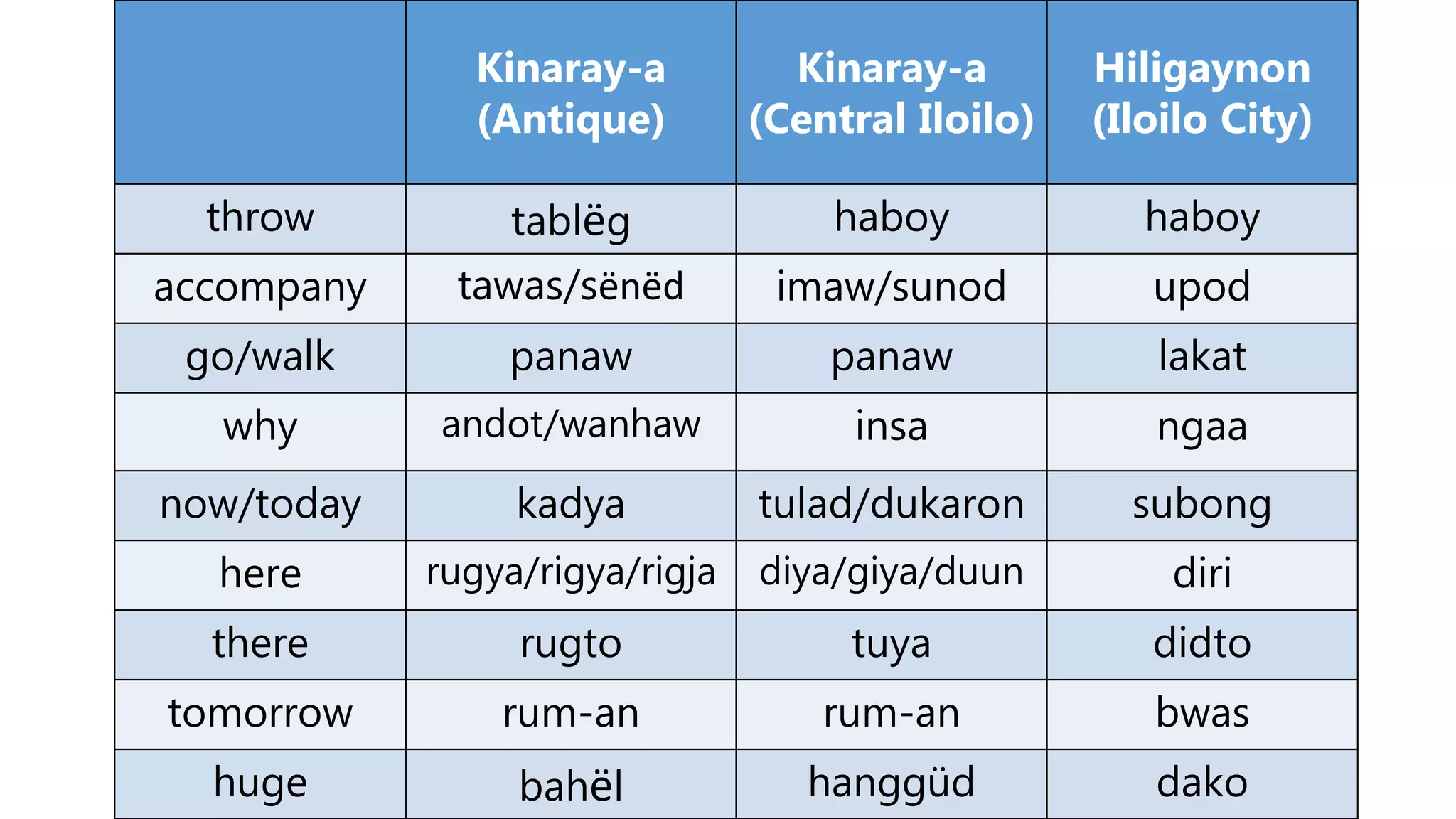

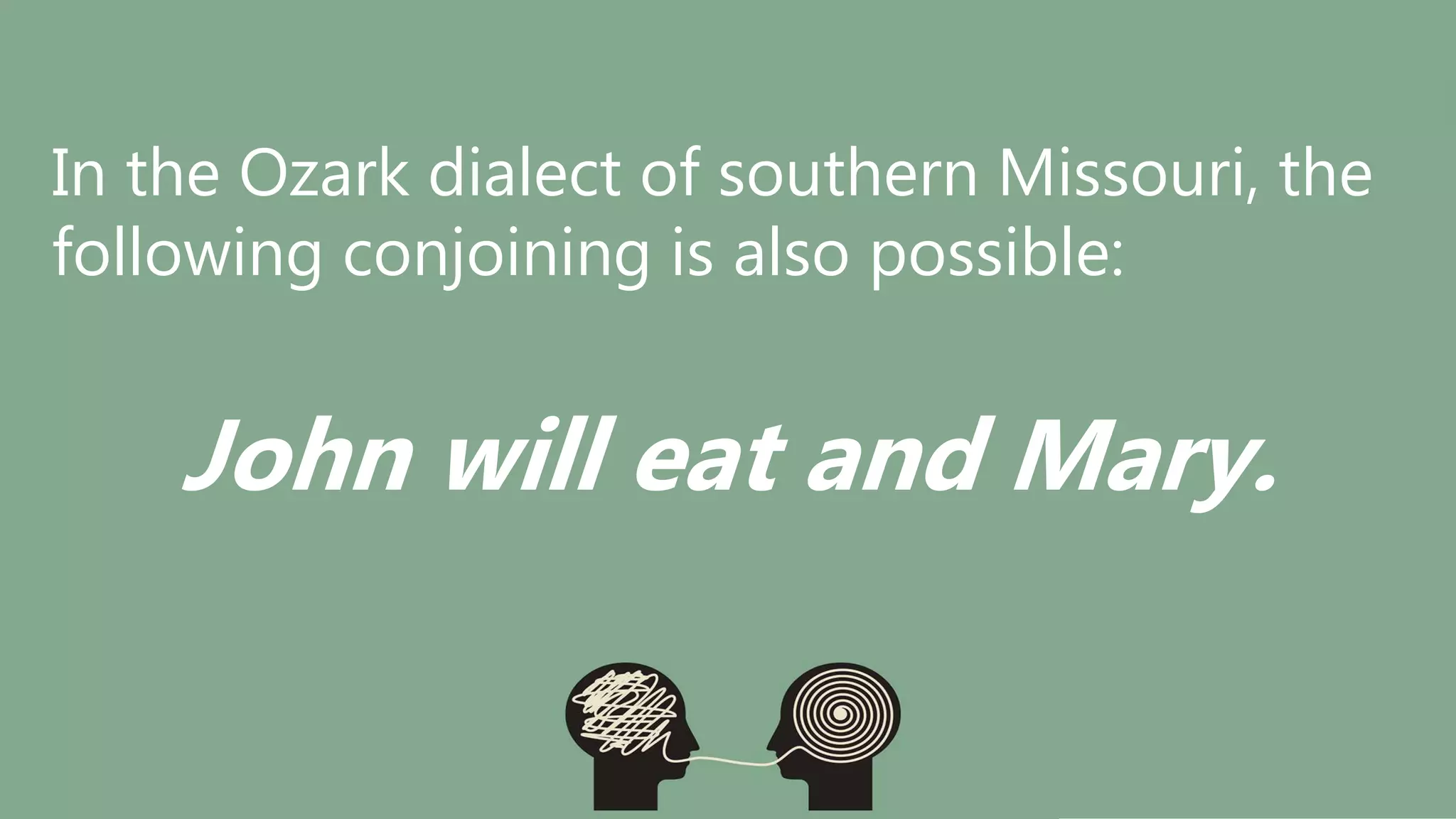

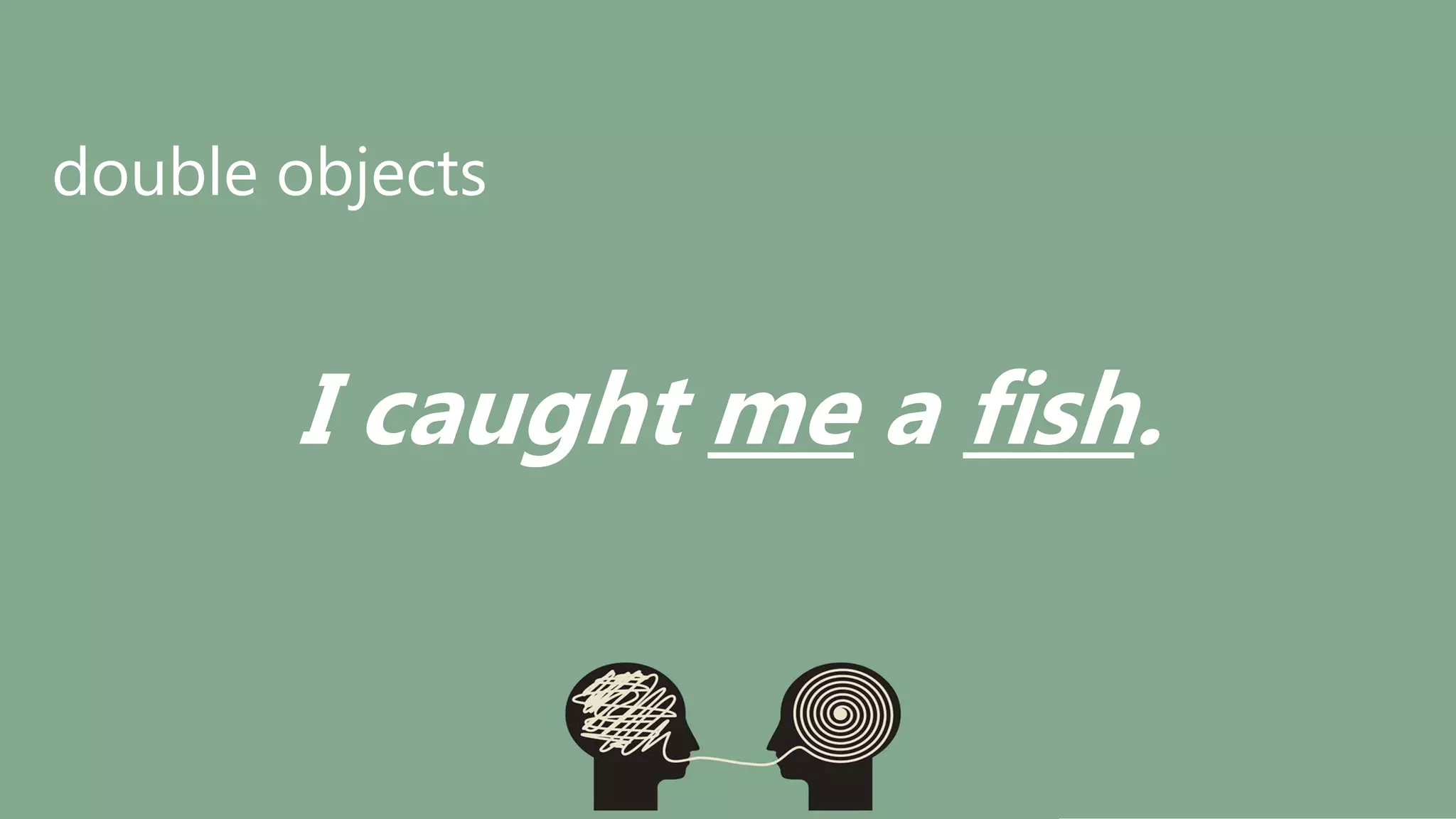

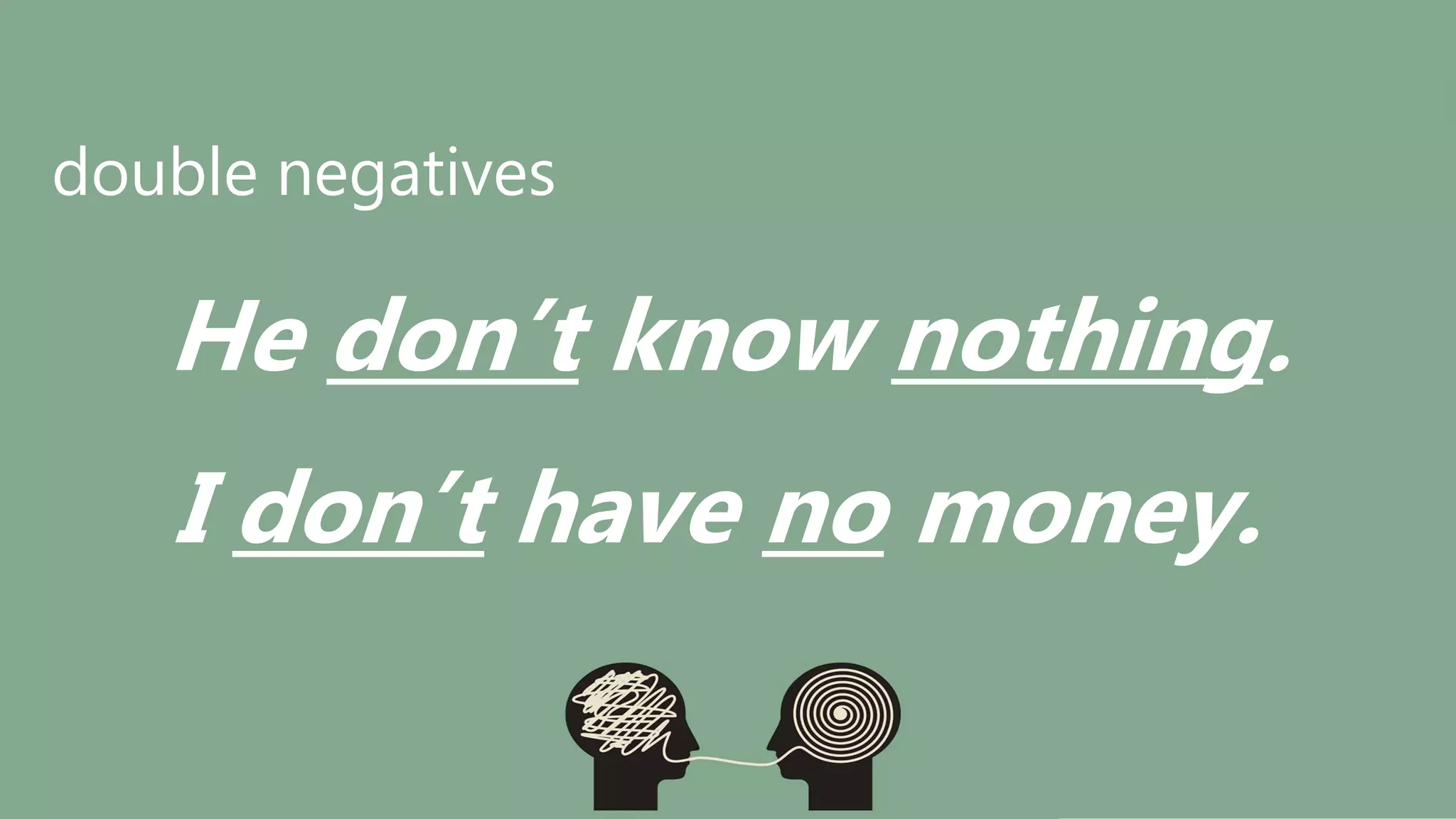

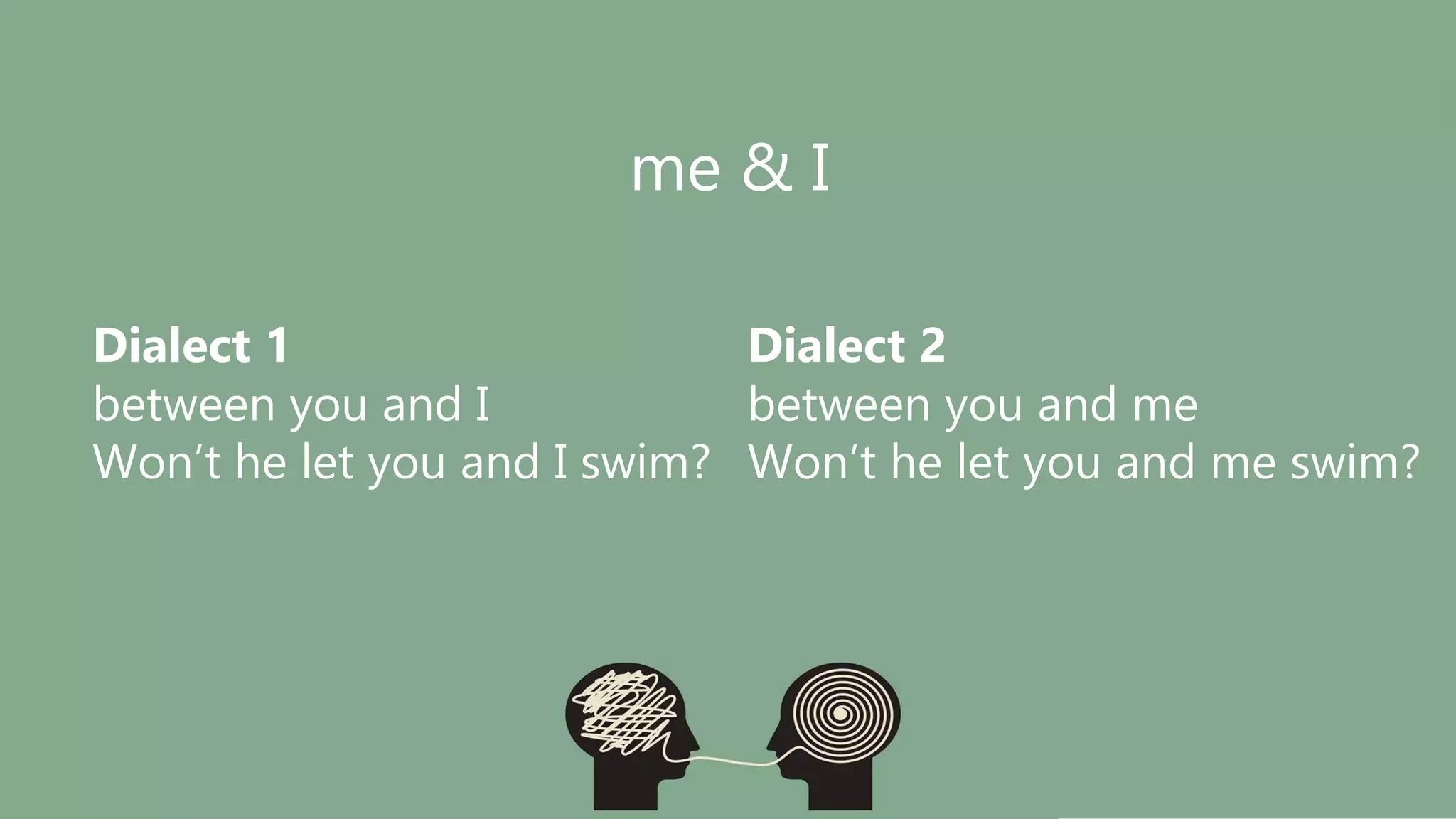

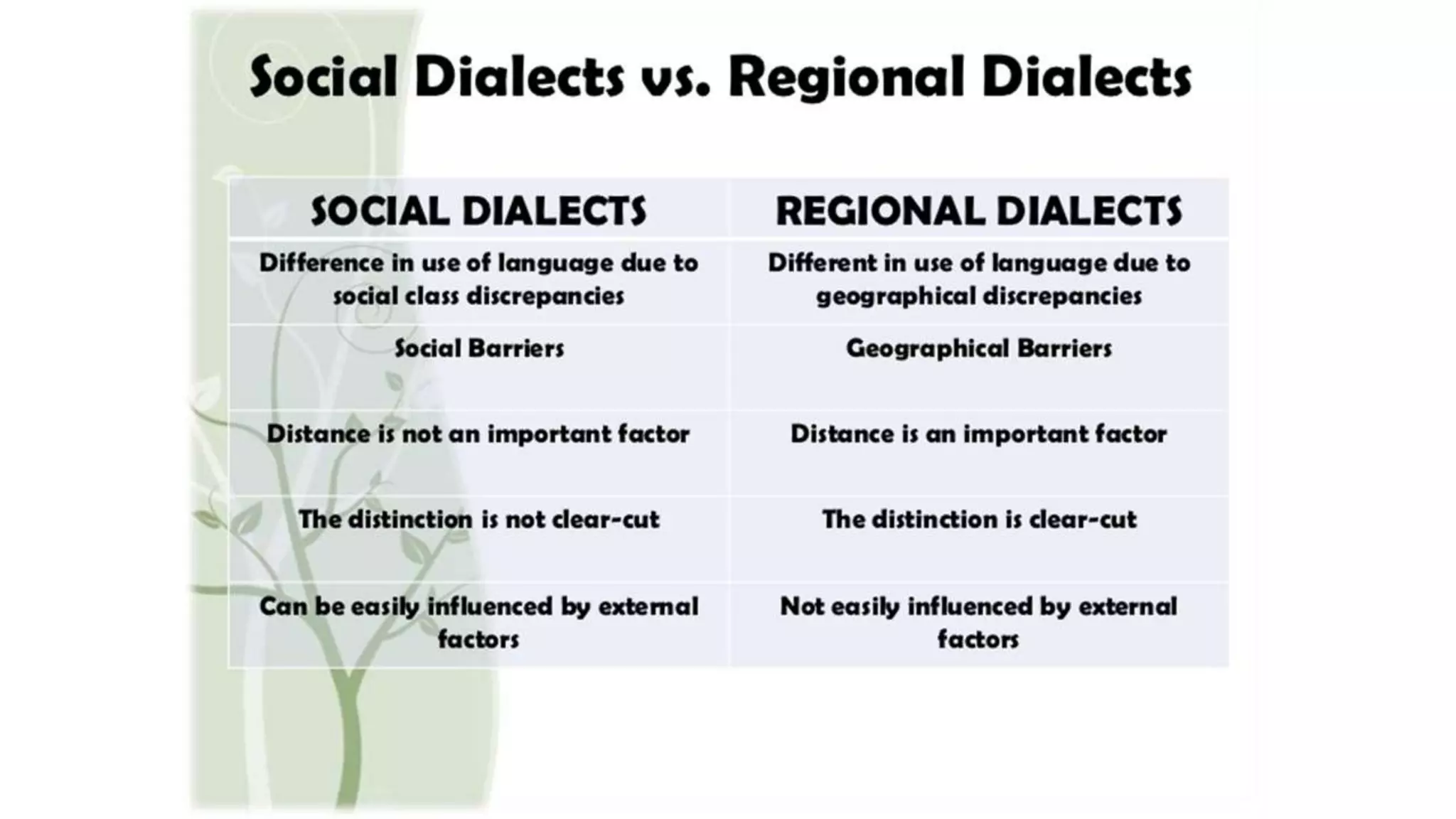

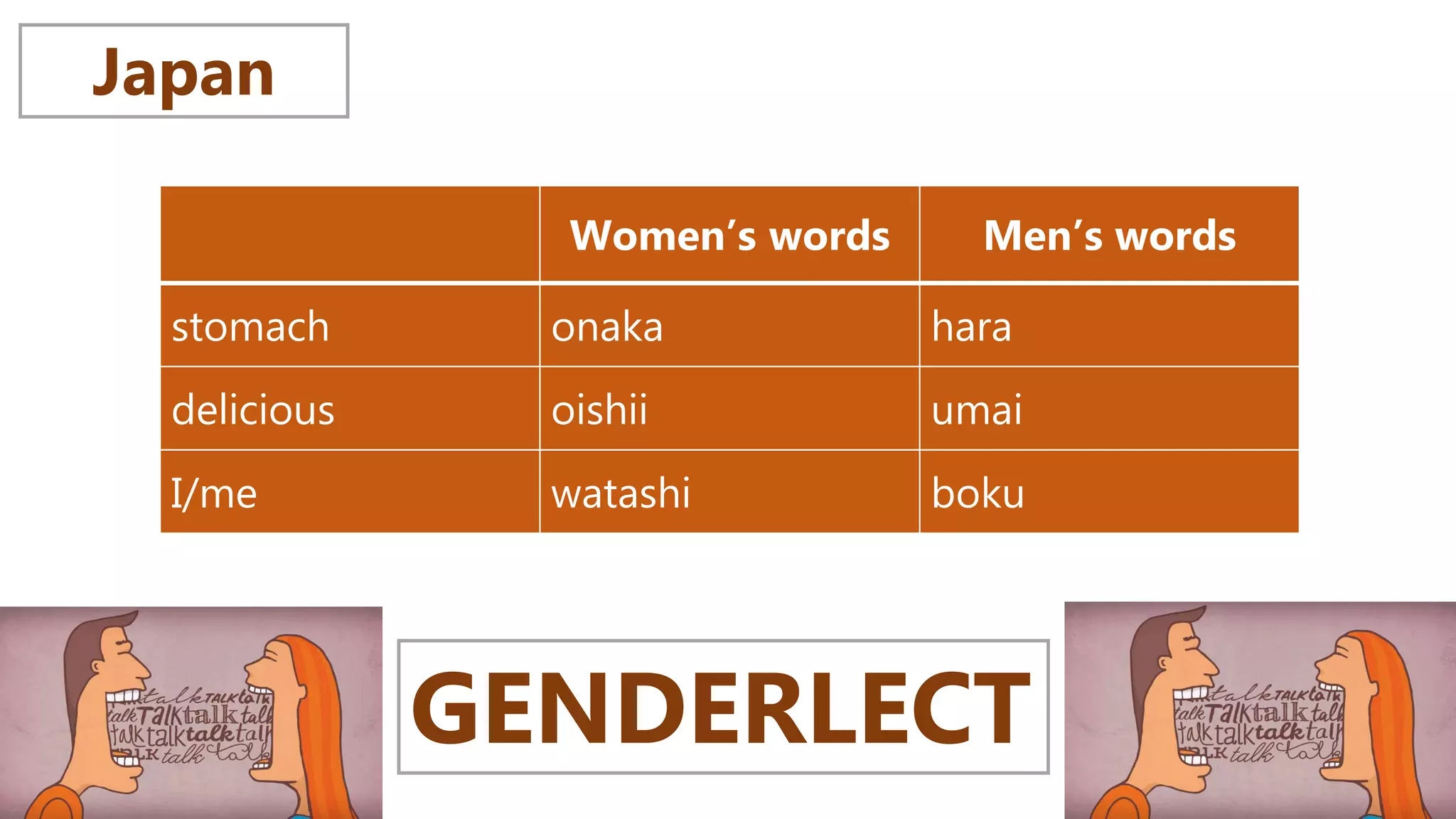

Regional dialects are variations of a language that differ based on geographic region. They can vary in pronunciation, word choices, and grammatical rules. Examples include different pronunciations of words like "luxury" between American and British English. Regional dialects also vary lexically, with different words used to refer to the same objects in different places. Additionally, regional dialects exhibit syntactic differences, such as the use of double modals or objects in some areas. Social dialects arise from social factors and can be based on socioeconomic status, ethnicity, gender, and other social attributes.

![48% of the Americans pronounced the mid

consonants in luxury as voiceless [lʌkʃəri],

whereas 96 percent of the British

pronounced them as voiced [lʌgʒəri].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/regionalandsocialdalects-170507050306/75/Regional-and-social-dalects-15-2048.jpg)

![Sixty-four percent of the Americans

pronounced the first vowel in data as [ā]

and 35 percent as [ä], as opposed to 92

percent of the British pronouncing it with

an [ā] and only 2 percent with [ä].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/regionalandsocialdalects-170507050306/75/Regional-and-social-dalects-17-2048.jpg)