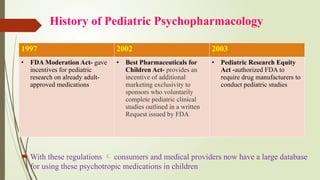

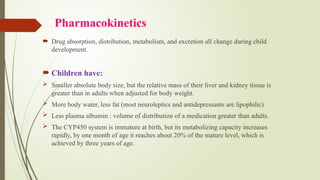

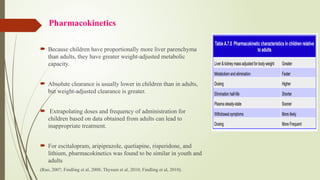

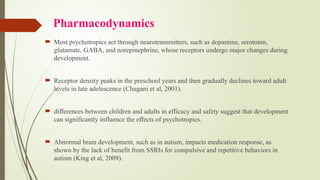

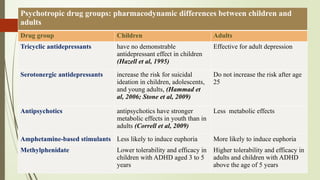

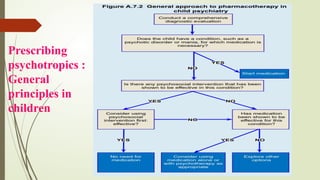

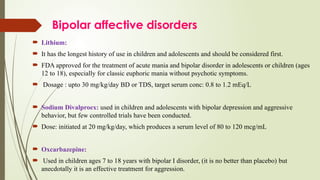

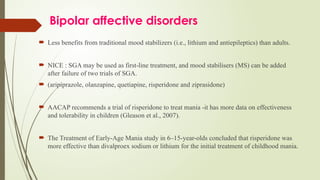

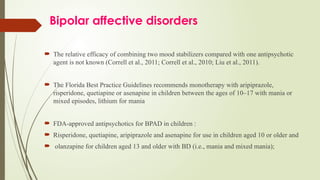

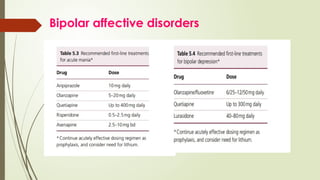

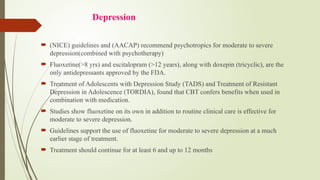

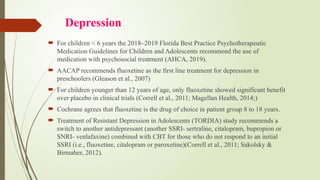

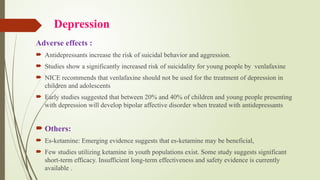

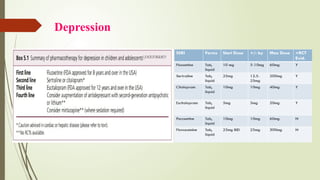

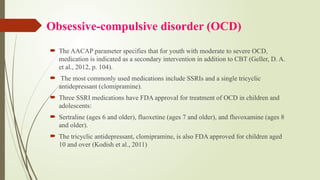

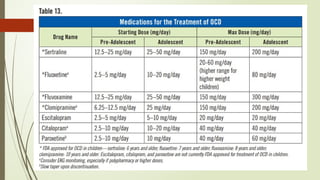

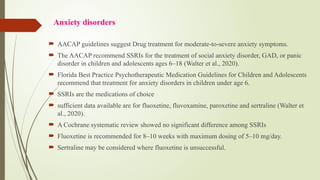

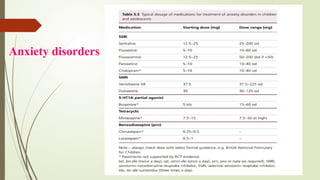

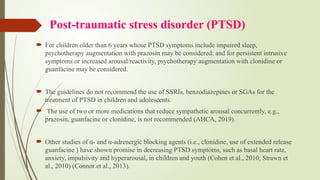

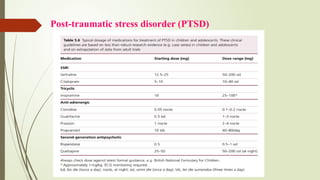

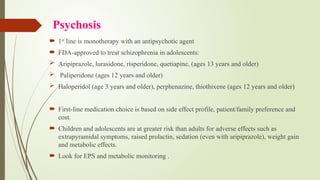

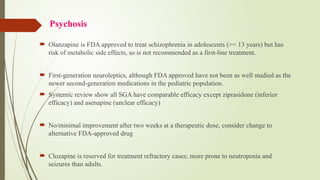

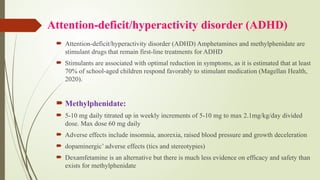

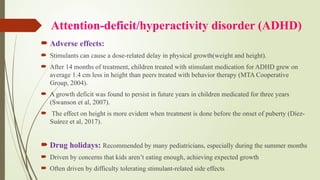

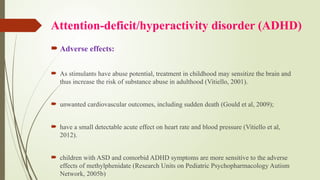

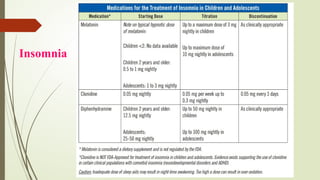

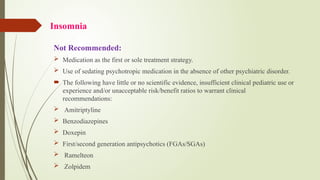

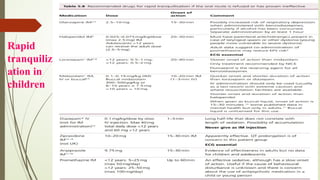

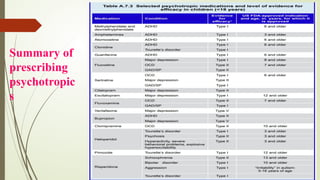

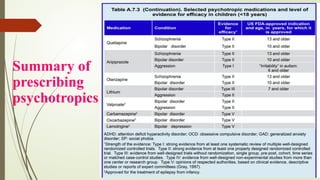

The document discusses the use of psychotropic medications in children, addressing their history, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and prescribing principles for various mental health conditions. It outlines the differences in medication effects between children and adults and provides guidelines for treating conditions such as bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD, and OCD. Recommendations emphasize the careful selection and monitoring of medications due to the distinct developmental factors in pediatric populations.