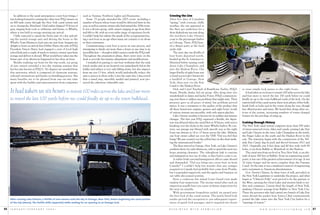

PDQ Yachts builds powercats in Whitby, Ontario. Each spring, when the harbor ice melts, they hold a flotilla cruise to transport the newly built boats to their owners. In 2005, 14 new boats needed transport. The author joined the flotilla with his new 34-foot PDQ powercat, Elixer. Over 8 days, the flotilla cruised 800 miles from Whitby through the New York canal system and onto the Hudson River, passing through over 50 locks. Despite rainy conditions, the trip provided the owners an opportunity to learn about their new boats and bond as a group through shared experiences navigating the historic canals.